Award-winning illustrator Hilary Jean Tapper illuminates the craft, quandaries and processes of creating children’s books with three visiting international illustrators.

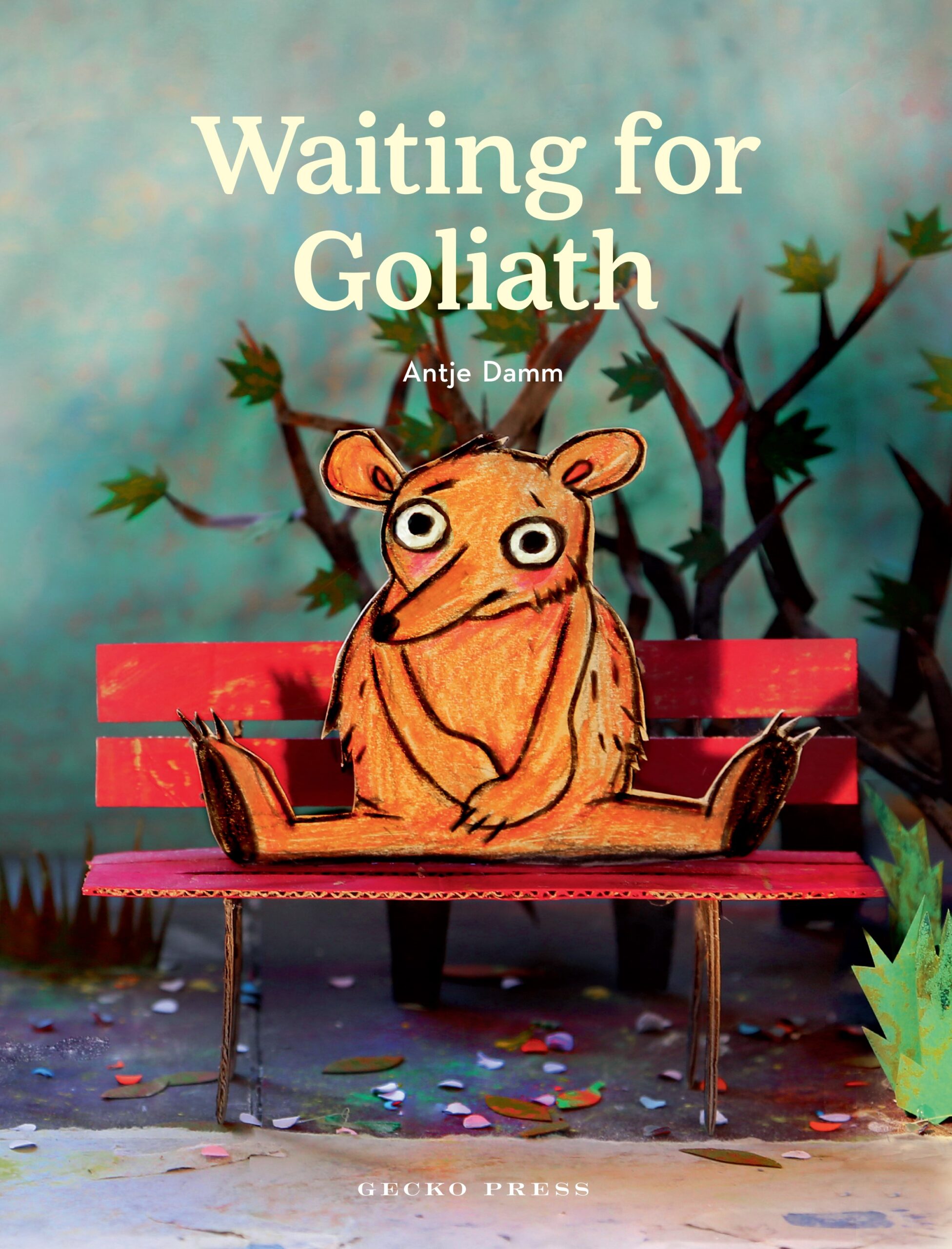

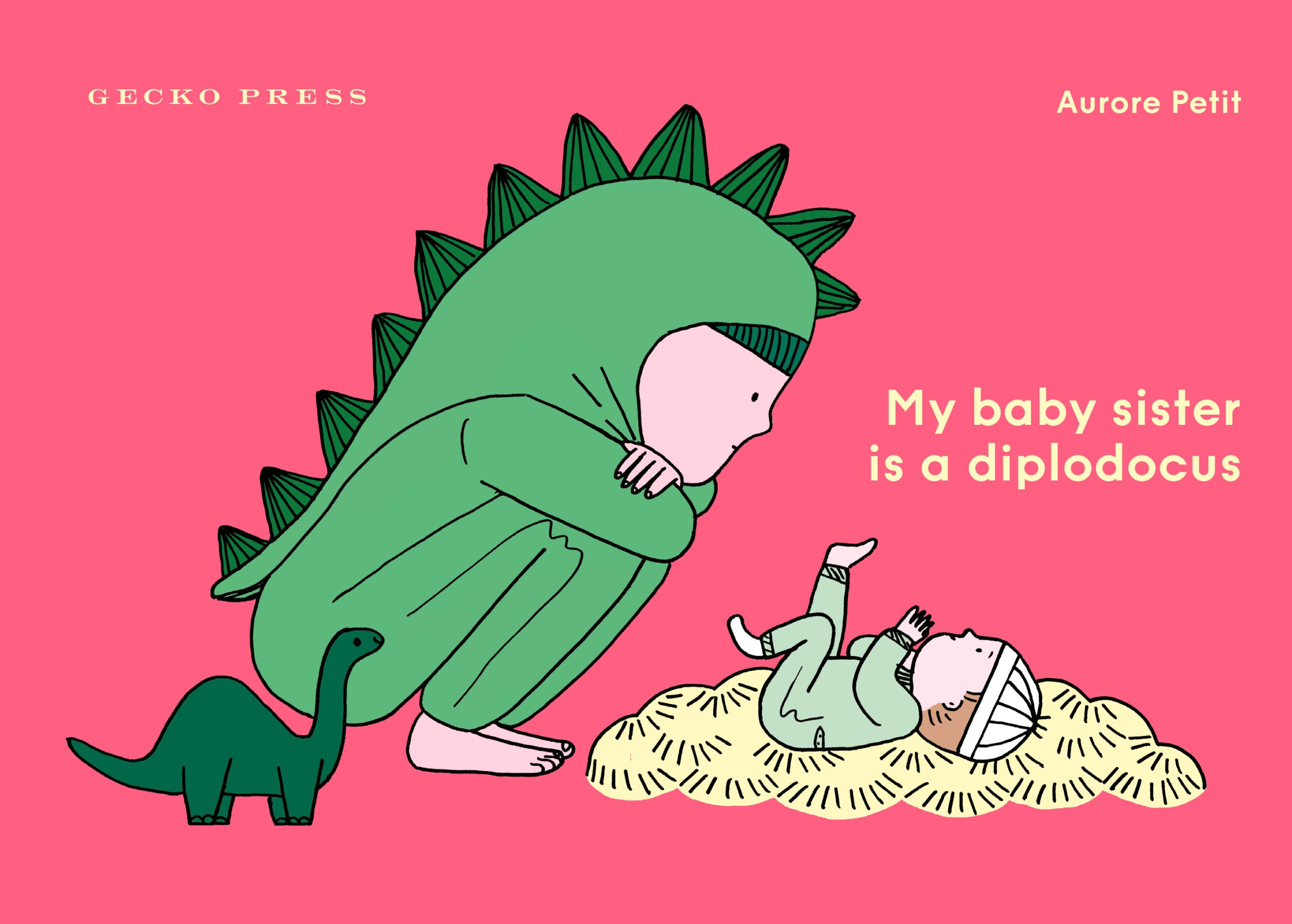

Picture book illustration is a small profession within New Zealand, with few opportunities to come together to celebrate and nurture our practice. As an illustrator based in Christchurch, it’s a rare day that I get to talk with another illustrator and hear about their inspirations and challenges within our discipline. In anticipation of the upcoming Picture Me illustration festival, featuring European picture book illustrators Antje Damm, Piotr Socha and Aurore Petit, I wanted to ask them some of the key questions that arise in my daily illustration practice.

Their answers give insight into their individual processes and orientations within their craft and highlight the unique and versatile practice that illustration is. It can be difficult to define. It can sometimes feel driven by commercialism. It can occasionally be quite confronting and vulnerable to tell stories through pictures. Antje, Piotr and Aurore’s answers demonstrate the highly personal yet open field that illustration practice is: the endless possibilities that await one willing to dive into the craft of picture books, and their works are a testimony to this.

Hilary Jean Tapper (HJT): How do you define illustration, and how is this distinct from other visual art forms?

Antje Damm: For me, illustration is a narrative form that is on an equal footing with text. Both can tell their own stories, go their own way, enrich, contradict or complement each other. I don’t think it’s right that illustration is often seen as the “little sister” of fine arts and doesn’t get so much attention. For example, there are hardly any galleries that exhibit illustration. However, I must also say that the pictures I make rarely stand alone from the context of the story, so they are a part of an overall work, and perhaps that’s the difference to a painting that stands alone.

Piotr Socha: I don’t like to theorise. I am a practitioner and not a theorist. It is difficult to give a simple and unambiguous definition of illustration—to be honest, I have no need for such definitions. The illustrator has a dialogue with the text he illustrates. Sometimes he describes it faithfully, sometimes he comments on it wittily. I have always looked for fun in the work of an illustrator. Playing with convention, with form, with style. That is and has been important to me—to have fun. My job is to relate the illustration to the text, not necessarily to literally show what the text describes. I try to make my illustrations add value to the text. The image and the words create a story.

Aurore Petit: I see illustration as an applied art, which is, to my mind, more connected to craft, or in the service of something, like communication, story, or even just a message or an idea. In this perspective, the question of the recipient and context is always present. I guess the image is supposed to speak for itself.

HJT: What, do you believe, is the fulfilment of the craft of “illustration”, and how do you aspire for this in your work?

Antje Damm: I didn’t learn to illustrate, because I am an architect, and always approached the matter completely intuitively. I’m still looking for ways and I enjoy trying out new things all the time. It’s not important to me to have a style or a certain technical language that people recognise me by. I would find that boring. Every book is a new challenge for me, and I always start from the beginning thinking about which visual language I´ll choose and how I can bring text and image together. Bringing these two narrative possibilities together as skilfully as possible is always a new challenge for me. I make books that are very different from each other, so this can also happen in different ways.

Piotr Socha: I prepared myself for illustration and book design for many years. I completed a diploma in book illustration at the Academy of Fine Arts, but for the next twenty years I did mainly press illustration. The thousands of drawings I did for newspapers were training before doing children’s books. I was constantly learning during those years, and I continue to learn. I learn a lot by drawing—by looking at the work of other cartoonists. I scan the world around me. I learn about different styles, techniques and conventions. Then I try to surprise myself, do something I haven’t done before. I am trying to tell a story known for a long time in a different way. Talent is overrated. I think my talent was average, but it developed through the thousands of drawings I did. Ten percent talent and ninety percent work will give a better result than ninety percent talent and ten percent work. I highly value intuition and a critical sense. Looking critically at what you do allows you to develop.

Aurore Petit: Actually, I don’t truly consider myself as an illustrator, as I imagine the whole book. For me, the illustration is one part of the project. In this sense, in my work, illustration is one medium among others to build projects, tell stories and express ideas. Over the course of my books, I have realised that illustration is more and more not an end in itself but a tool. In my pop-up books for very young children, the fold, the movement, the wording and the image are completely intertwined. I can’t tell if that’s still illustration. I don’t put the illustrations in the foreground of my projects. It’s more about the book in its entirety.

HJT: How do you protect and honour your creative process and ideas whilst working commercially as an illustrator?

Antje Damm: For me illustration is an experimental game, and we should just enjoy it! What’s important is that books work and that people can do something with them, that they trigger thoughts, make you want to relive the story, that you are simply touched by it, or that it is fun. Since I illustrate and write, the entire development process is in my hands and I have a lot of freedom. I don’t think about whether a book will sell when I’m working on it. That would interfere with my creativity. When I design a book, I keep the age of the children who will be holding it in mind, but I also think that everyone should discover something for themselves in the book, including adult readers. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be a good book!

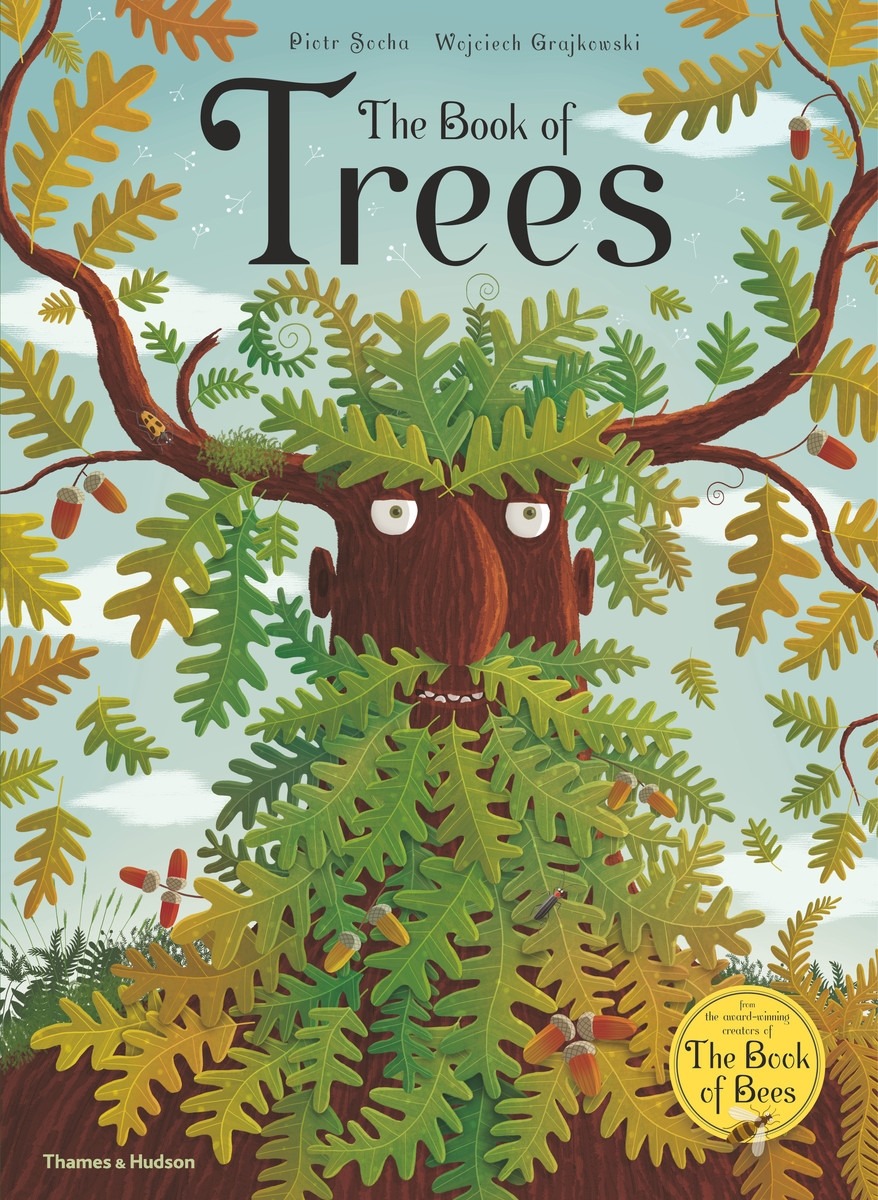

Piotr Socha: For the past ten years, I have only been involved in children’s books. I don’t do any commercial illustrations. Books have already been made on every subject. Thousands of books have been written about love, friendship, vampires, dinosaurs, ants, talking animals, dragons, princesses, etc. What is important is HOW I tell the story, what form the story will take. A good illustrator can retell a story that has been known for centuries, but he has to have a compelling reason for doing it, or some really good, expressive graphic idea. I’ve done books about bees, trees and the history of hygiene. Other authors have also created books on these subjects, but I believe I can tell the story in my own way.

Aurore Petit: Good question. Thankfully, today clients come to me asking me to illustrate something that looks like my drawings. Earlier in my career, clients sometimes asked me to change the way I draw my characters or tried to bring me to a more mainstream style. That was really painful and could break all my confidence. At this time, like lots of illustrators, I suffered from the fact that many clients asked me to work for free (or almost), arguing that we, artists, work by passion. This argument is no longer tolerable. I’ve been represented by an agent for a few years, and that really helps for this aspect of the job. She frames all the commissions, and special requests are always paid. Obviously, sometimes I work on boring projects, and it feels like I’m wasting precious time! But in this case, I think about the money, about my loss of time allowing me projects that I will do with pleasure and less stress when I am rich!

HJT: Where do you find your inspiration and courage as an illustrator?

Antje Damm: People often think I make books because I have four children. That’s not quite right. Of course I experience many stories with my children—I observe what interests them and some of our stories have actually ended up between the covers of books. Basically, I remember my own childhood very well. I can still recall the feelings, thoughts and fears well, and that’s a great source of inspiration. But I’m also a curious person and go through the world with my eyes open. I soak up small events and experiences, memorise images that I see on the street, in museums, in books or in nature. All of this influences my work. I don’t think you can create out of nothing; you have to look and listen carefully. And then, very important for my work is that I’m interested in philosophising with children, the thoughts and adventures that take place in their heads. Perhaps that’s one of the most important reasons why I make the books, because I want to give children space to communicate.

Piotr Socha: A great inspiration is nature. You have certainly heard of Antoni Gaudí. When I still knew little about him, I admired his imagination. But when I learned about his inspirations, I understood his works because in them these inspirations are hidden. Gaudí was asthmatic as a child and his doctor recommended that he spend a lot of time in the countryside. Little Antoni was a brilliant and careful observer of nature. There are little museums next to his buildings, and in them are showcases in which lie animal bones, snake skeletons, shells, pinecones, palm leaves, wax patches built by bees. When I saw them, I understood these ingenious buildings. I saw that the columns resembled palm trees, the roofs resembled the skin of a snake, and the stairs resembled the inside of a snail shell, and so on. Yes, nature is very inspiring.

Back to New Zealand, one of my idols is Sir Peter Jackson. I will frankly admit that I was not fond of fantasy literature until I saw Lord of the Rings, which is an absolutely brilliant work that delights, moves, laughs and makes you think. My book The Book of Trees has the ents, talking trees from Tolkien’s trilogy on the cover.

Aurore Petit: I find inspiration for my books in my everyday life. It can be sports on TV, a walk in the forest, a discussion with my kids, landscapes… When I don’t know what to draw, I sometimes draw a stream of consciousness, like an object that it’s in front of me, and I make it talk. That’s often funny to do! I believe in playful tips to find stimulation and inspiration. But I also often visit exhibitions (painters like David Hockney really give me the urge to paint, but I don’t dare!), attend shows (choreography, contemporary dance, is really inspiring to me). Music allows me to lock myself in a bubble and can influence my line, the rhythm of my drawing, and sometimes lead me to experiment with abstract graphics (music like Murcof, Susumu Yokota, Arp, Olafur Arnalds). All this is material from which I can draw when inspiration is not there.

HJT: In what ways do you experience the process of illustration come alive in your work? Do you encounter moments in which the art leads, unexpected surprises unfold, or mistakes turn into revelations?

Antje Damm: I often start a book with the pictures. They are the first thing that comes into my head. The story develops in parallel. Sometimes it’s a character or a certain place that triggers an idea for a picture book, or I start with a picture and don’t yet know exactly how the story will continue and what will happen. When I build cardboard models for my illustrations, it’s a very playful, experimental approach. As an architect, I built a lot of exact models, now I can work very freely and unconventionally, which I think is great. I build, tear away again, change or add colour without planning exactly. Ultimately, even when photographing, there are still a lot of possibilities due to the perspective, the image section and the light. This also means that I have to trust chance, because I can’t plan everything.

I’ve never written a story and then illustrated it or made a storyboard, because when I’m taking pictures, new ideas for the story suddenly come to me, which I then incorporate spontaneously. So it’s a somewhat chaotic process and perhaps people who have studied illustration would describe my way of working as very unconventional.

Piotr Socha: The hardest thing is to start working on a book. I sit with a pencil in my hand over a blank sheet of paper and just start drawing. At first, the job doesn’t go well for me, but I keep drawing. Sometimes it takes a few days, but eventually something starts to emerge from these sketches. My intuition tells me that this idea is good and that one should be abandoned. I listen to my intuition. The world I draw is not perfect, ideal. It is crooked and skewed. I try to play with drawing like a child. I try to be like an amateur artist. This element of play is extremely important to me. I try not to take what I do too seriously. Picasso has said that this childlike joy of creation is extremely important and creative and that he tries to create like children. My work is a search for the right form for a story. I like stories that are surprising and not obvious. I try to make my books like that.

Aurore Petit: Of course it happens! But it’s hard for me to accept losing control. I would like so much to be this free artist who assumes the unexpected surprises, publishes raw drawings, and is completely confident with experimentation. But I have the good student syndrome, I often need to redo, perfect things, clean… It could take the rest of my life to deconstruct and let it go! The experiences I have with children during the workshops are very helpful. Their way of understanding form and colour in a raw and organic way is an example of freedom. They live the artistic experience with spontaneity, in a very natural and often playful way. These moments are precious and remind me that drawing is also a visceral and innate form of expression.

Hilary Jean Tapper will be in conversation with Antje Damm, Piotr Socha and Aurore Petit at Tūranga Library, Christchurch at 5:30 p.m., Friday, 27 September 2024.

Picture Me festival will run events for adults and children from 11–19 September 2024 in Wellington and 27–28 September 2024 in Christchurch. Visit the Gecko Press website for details on discussion panels, networking events and an illustration exhibition.

Picture Me is brought to Aotearoa by Gecko Press, the Goethe-Institut, the French Embassy and the Embassy of the Republic of Poland, funded by the Franco German Fund, with additional funding support from Creative New Zealand and the Polish Book Institute.

The Book of Trees

By Piotr Socha & Wojciech Grajkowski

Published by Thames & Hudson Ltd

RRP: $40.00

Hilary Jean Tapper

Hilary Jean Tapper is an award-winning illustrator based in New Zealand. She creates picture books, and works as a lecturer and researcher. Her awards include the ABIA Children’s Picture Book of the Year, Storylines Noteable Award, and Forevability Book Award. Hilary illustrates picture books with Hachette, Allen & Unwin, Affirm Publishing, and Gecko Press. She uses ink, watercolour and pencil.