The intimidatingly-talented author of two acclaimed poetry collections, owner of the best fringe in New Zealand lit, and all round book-ish Good Sort sat down with Rachael King to talk about making the leap from poetry to kidlit and the road to becoming a unique new voice in children’s books.

The first sentence of Jane Arthur’s new middle grade title Brown Bird is set to go down as one of the greatest in New Zealand children’s books ever:

“The morning I met Chester was hot and still, one of those very-summer-holidays kinds of mornings when you wake up early and see the day spread out ahead of you like a vast, glinting sea, if the sea was something calm and full of sensible options for passing the time, rather than a dark, deep pit of unknown danger.”

It starts with the cosy, nostalgic promise of ‘summer hols’, all ice cream and messing about in boats, but ends with a sly subversion and a challenge: pay attention! This character is no Milly Molly Mandy, despite the attractive map at the start of the book. We’re in for someone altogether more complex.

The first sentence of Jane Arthur’s new middle grade title Brown Bird is set to go down as one of the greatest in New Zealand children’s books ever.

I mean it when I say it’s one of my favourite first lines ever. Did you start with it or did it come later?

Thank you very much! Can I put that on a sticker and secretly stick it on every copy of the book in bookshops please? I definitely did not start with this sentence. It came after another writer generously suggested I needed something to frame the story, as an early draft opened clunkily with the action – and not in a good way like can sometimes happen. That advice unlocked the opener in one go, because by then I knew the main character inside and out, her wry voice and anxieties.

What I love most about Rebecca is how you give a voice to the kids whose inner lives are often hidden from us. We’re party to thoughts such as, ‘My face looked weird in the mirror without [my glasses], like there was too much skin and not enough face.’ Or when she compares herself to a tree that’s been hit by lightning: ‘If you glanced at it, you’d never know it was on fire at all. That’s how I felt sometimes. Like I was burning inside.’ I’m not sure we see many characters like this in books (the closest I can think of most recently is Katya Balen’s October, October). Where did Rebecca come from?

Psychologically, Rebecca is mostly me, though factually we aren’t exactly the same. I didn’t learn of the concept of ‘introverts/extroverts’ until I was an adult, and if I had known about it as a child, I think I would have felt less of a social failure. It feels like it’s only been the last few years that people have been talking about anxiety, too, and I’ve realised how common it is. I was determined to present an introverted and anxious character to young readers and show them that while being that way has its challenges, it’s also a completely viable and normal – human – way to be. It even has its benefits.

How easy was it for you to reach for the right words to describe these complex inner thoughts and feelings?

These parts were the easiest to write, by far. It has always been external action – scenes where things are happening – that I’ve found the hardest (excruciating) to write. If I could write a novel made up of only inner thoughts and feelings, I would.

…while being [introverted and anxious] has its challenges, it’s also a completely viable and normal – human – way to be. It even has its benefits.

The book has been referred to as ‘casually inclusive’ which I love. Did you model the characters on people you knew? Did they just appear on the page or did you plan them quite thoroughly?

I didn’t model any of the characters on real people. The closest any of them came to real people was creating the same emotional effect on me as people I’d met in real life, if that makes sense at all. But the ‘inclusivity’ was both intentional and not – I think it comes from truly seeing what the world looks like. I was speaking to someone who read the book recently and she said, ‘They’ve got to live somewhere’, as in: yes, there are various queer characters and ethnicities and genders and ages on Rebecca’s street because where else would they live? They’ve got to live somewhere. But I didn’t set out to ‘tick boxes’, gross, it’s just who emerged from each house as I wrote. I was more focussed on representing a supportive and welcoming community that gave Rebecca no objective reason to be shy of them.

How has being a poet helped your prose writing? What were the challenges for you in crafting your first novel? What was the process?

I’m a slow writer. I joke – not really joking, though – that the longer I spend writing, the shorter my word count gets: I edit as I go, constantly paring back and getting rid of unnecessary words. That’s why I write poetry, because it’s the standard process. Taking that process, which feels natural to me, and applying it to long-form fiction was … well, I wouldn’t exactly recommend it. Writing poetry does help with word choice and rhythm, though, I reckon.

A lot of work was initially done free-writing to get to know the main characters. I chipped away at that for about a year. Eventually, I decided I needed to get on with it, so I constructed the nerdiest Excel spreadsheet you’ve ever seen – it’s colour-coded and beautiful – and mapped out the plot of the novel using the three-act structure (after lots of Googling about what that is), then I figured out what would happen in each chapter. This meant I could write whatever bit I was in the mood for each day, because I knew exactly where I was going and what I was doing. The full first draft was written in a few months once I’d done that plan. And once the spreadsheet was made, it never changed – from first draft to final published book, every chapter still contains the same content, in the same order, even after external edits. The drafts and re-drafts were fiddling and clarifying and beautifying within this framework.

You’ve worked in children’s books before: at Gecko Press; as a judge of the New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults (twice); and of course as a bookseller selling children’s books. You are also one of the founders of The Sapling. What drew you to working with children’s books, and did you always intend to write for kids?

This is a very interesting question! I’m not exactly sure why I’ve been drawn to working with children’s books, but I do know I feel sad for adults who dismiss them as ‘only’ children’s books. They can be so rich! They can also be so fun!

When I started in bookselling over 20 years ago, in my very early twenties, picture books were the first children’s books that blew my mind. I was like, is anyone else seeing this? Is anyone else clocking the intricate interplay between text and image here? How they are (well, can be) works of art that are greater than the sum of their parts? Done well, they’re poetry plus fine art plus art direction plus print production, all those details that I love.

Then I realised that children’s and YA fiction were basically just excellent novels that didn’t muck around – they had all the components of adult fiction, the themes and good writing and so on, but were guaranteed page-turners, just with child protagonists.

And that’s when I started on the road to campaign for children’s books being taken seriously by adults. I didn’t consciously think that I should write for children, it was just so obvious I would. I think we all still have every age of the children we were inside us somewhere and reading kids’ books helps us reconnect with them. As well as children’s books being for literal children, obviously!

I think we all still have every age of the children we were inside us somewhere and reading kids’ books helps us reconnect with them.

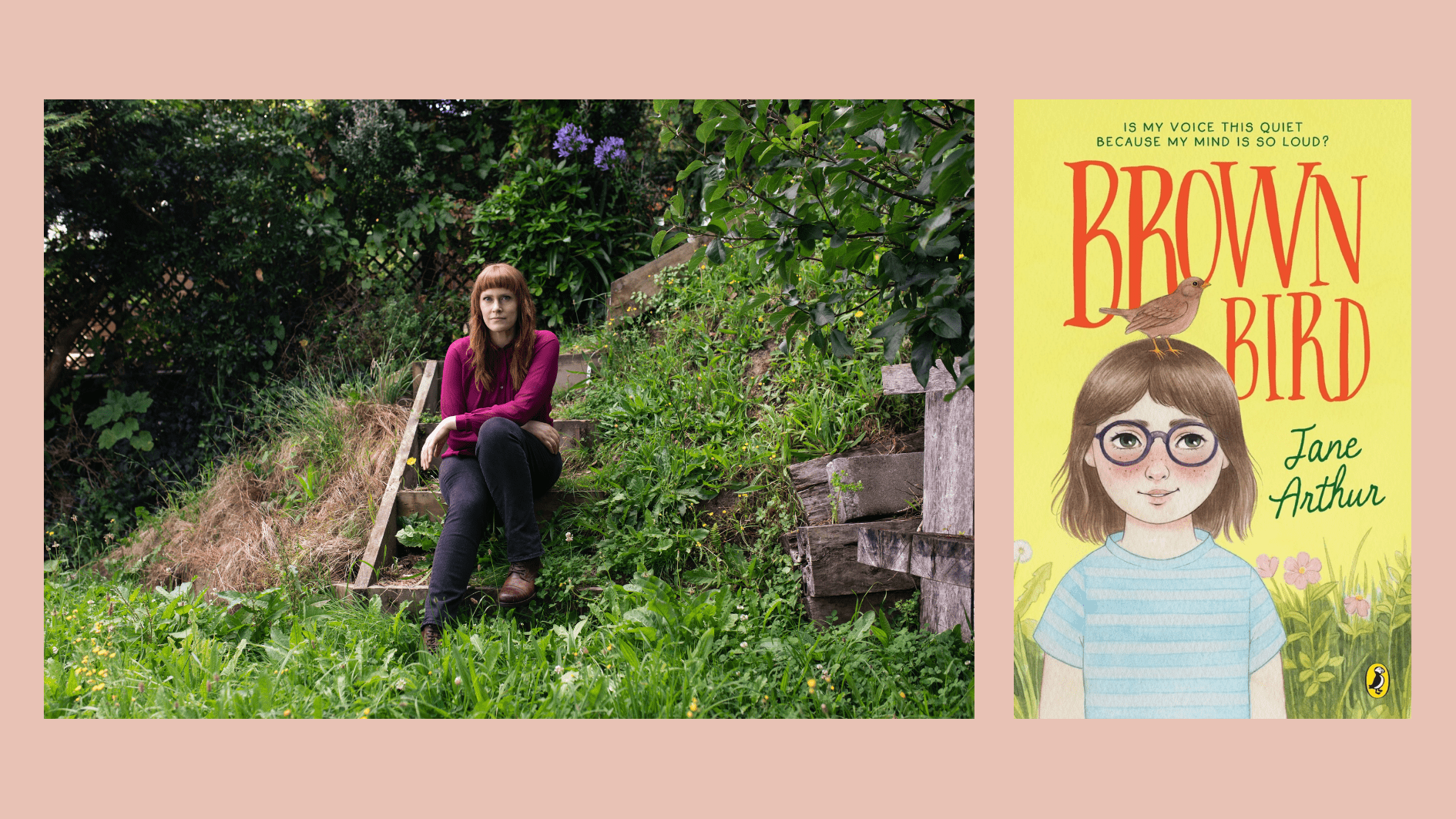

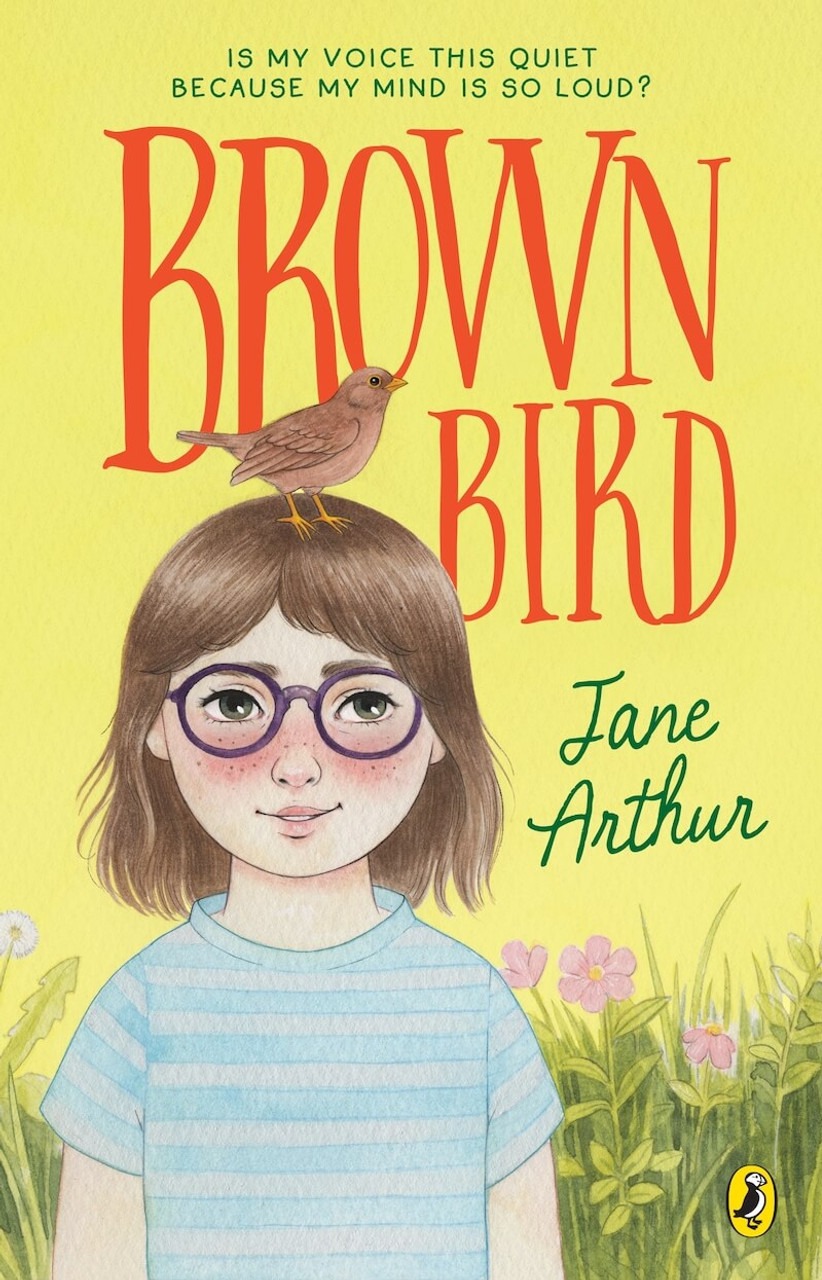

Tell me about the gorgeous cover. How did that come about?

I asked Catherine O’Loughlin, the children’s publisher at Penguin Random House NZ, if I could be involved in the design process of the book, as that’s always been part of publishing I’ve most enjoyed (to be fair, I enjoy the entire publishing process) and she kindly agreed, even though I admitted that their books and covers have recently been stunning so I’m sure they would have it under control. I then said that the only thing I knew for certain is that I didn’t want to have a picture of Rebecca on the cover, in case it messed with the picture of her in readers’ minds. But then Catherine emailed saying they’d come across an illustrator who they thought might be suitable and what did I think? It was Devon Smith.

I thought: you have got to be kidding me, this is spooky. I replied to Catherine and said, ‘I am flying to Dunedin tomorrow to be tattooed by Devon so YES PLEASE,’ and, ‘You know how I said no faces on the cover? Ignore me, because if it’s one of Devon’s sad sweet faces, then that is exactly what Rebecca should look like’. Next thing we have the beautiful cover with the summery yellow background and the wildflowers and weeds. It’s an actual watercolour, too, not digital. I love it so much. I love the fonts, all of it. Love seeing my name with the Puffin logo.

Can you share who some of your favourite contemporary children’s writers are?

Rebecca Stead, Karen Foxlee, Kate DeCamillo, Ursula Dubosarsky, Whiti Hereaka, Rachael King, Steph Matuku, T.K. Roxborogh…

Rebecca’s mum reassures her that “everyone’s weird. Absolutely everyone.” How important is it for children to know that what they are feeling is not a burden they carry alone? Or is Rebecca’s mum saying that, because she feels weird too, and she assumes that everyone else is?

It is so important to not feel alone – that is probably the main motivation behind me writing the book. More than wanting to show that Rebecca changed (she is fine as she is!), I wanted to show that she accepted herself. And truly, every single person has something about them that someone else would think is weird, or something about themselves that they feel ashamed of that is actually completely normal.

It is so important to not feel alone – that is probably the main motivation behind me writing the book.

I wanted to let Rebecca’s mum voice this message, rather than Rebecca learn it entirely for herself, because while the traditional thing in children’s books can be to let the kids go on the quest alone and fight the demons and have full agency, I wanted to show that sometimes you can have wise, supportive adults there to keep you safe. But I made sure to have Mum make mistakes too, because parents are human as well.

Chester is a beautiful character, all the more for Rebecca’s realisation that she hasn’t really seen his pain. One of the lessons I took away from the book is to not take people at face value, and that you never know what is going on in other people’s lives or inside their brains. Is that good advice?

Exactly. At the start, Rebecca doesn’t comprehend that worry can present in any way but quietness, so she thinks Chester must therefore be the opposite to her in every way. She comes to learn that people aren’t that simple. One of the first hints of this is when he’s too scared to go up the ladder in the plum tree, but she isn’t, so their bravery is switched for a moment.

Lastly, I just want to say that the sweetest moment was when Rebecca whispers to herself, “I feel sorry for myself,” because we are always told as children to stop feeling sorry for ourselves, or to be brave. So I love that acknowledgement that it’s okay.

I think the fact that emotional literacy is being taught at schools is revolutionary and will save the world. Screw being brave. Let’s all name our emotions!

Rachael King

Rachael King is a former literary festival director and a writer for adults and children. She’s the author of two middle grade novels: Red Rocks (2012) and The Grimmelings, which is a finalist in the 2024 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults.