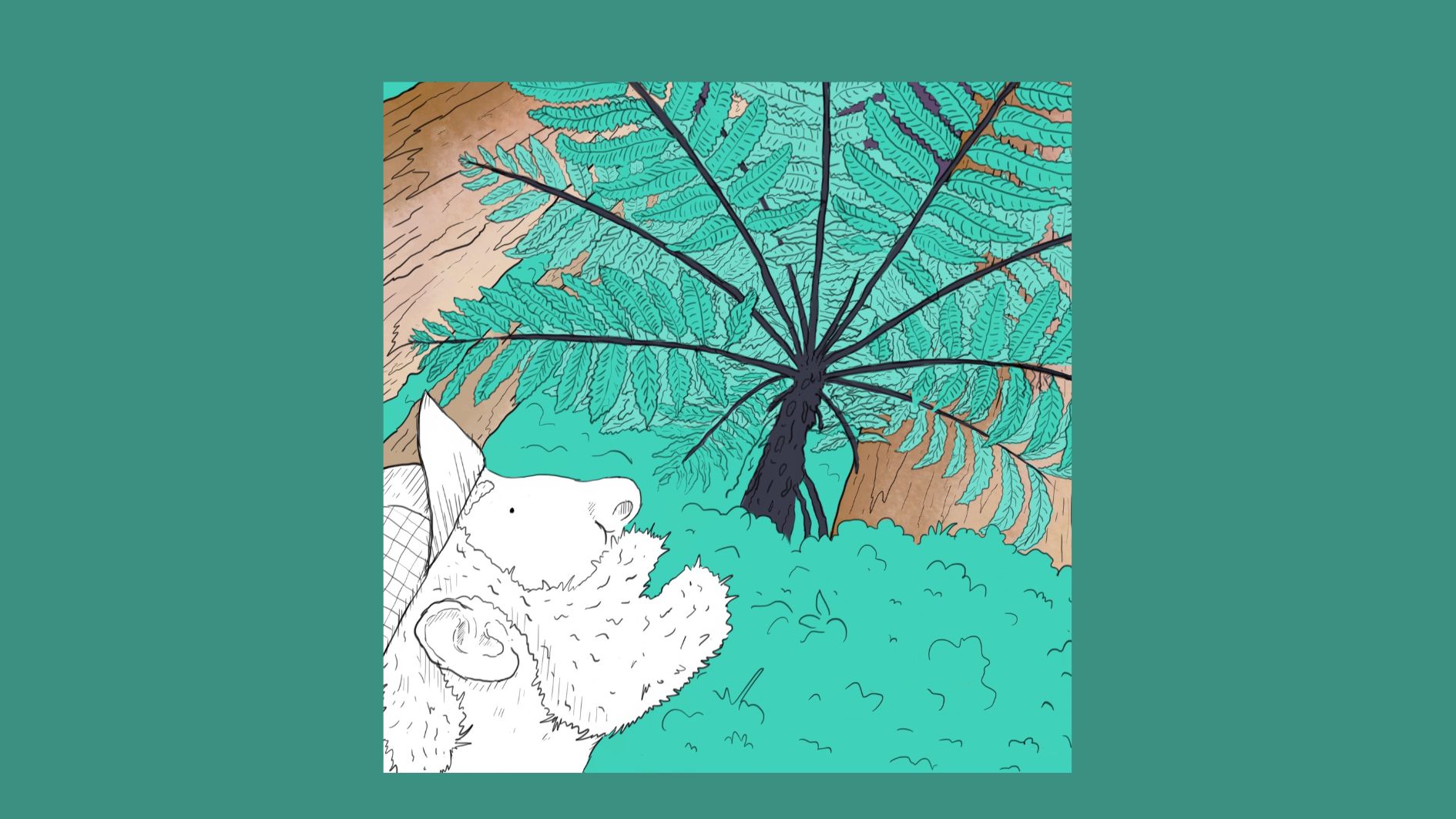

Steve Mushin with his book, Ultrawild, was the winner of the best children’s non-fiction book at the NZCYA Awards in August. Ultrawild is an entertaining thought experiment around the concept of rewilding to save the planet. Linda Jane Keegan reviewed the book earlier in the year and has now had the chance to dive in with all her questions about the ideas behind this incredible book.

Kia ora Steve! Congratulations on winning the Elsie Locke Award for Non-Fiction at the NZCYA Awards!

I’m on Cloud Nine—which also happens to be the name of a theoretically possible floating city proposal described in my book.

Ultrawild feels like xkcd meets European comics meets the IPCC, and it’s clear from the format how storytelling is a huge part of sharing this thought experiment. Who are the artists, designers, scientists, engineers and others who have influenced your approach to design and illustration—in this book and other projects?

Xkcd and What If (Randall Munroe) are huge inspirations—because of their science, but also their comedy. Ultrawild is fundamentally a design comedy. And of course ‘ligne claire’ comic artists like Hergé and Mœbius (Jean Giraud) have inspired me since forever. I spent my childhood flicking through Tintin comics—marvelling at how the scenes (particularly those involving explosions) were drawn. On design, I found a copy of Victor Papanek’s incredible book of environmental thought experiments Design for the Real World in my primary school library when I was about 10. That blew my mind. And from there I got into the experimental environmental designs of Buckminster Fuller and Hundertwasser and others.

How did the idea for this book go from concept to reality? You’ve spoken before about it developing organically, but can you tell us about how the early ideas transformed into what the book is now?

It’s been a long journey…

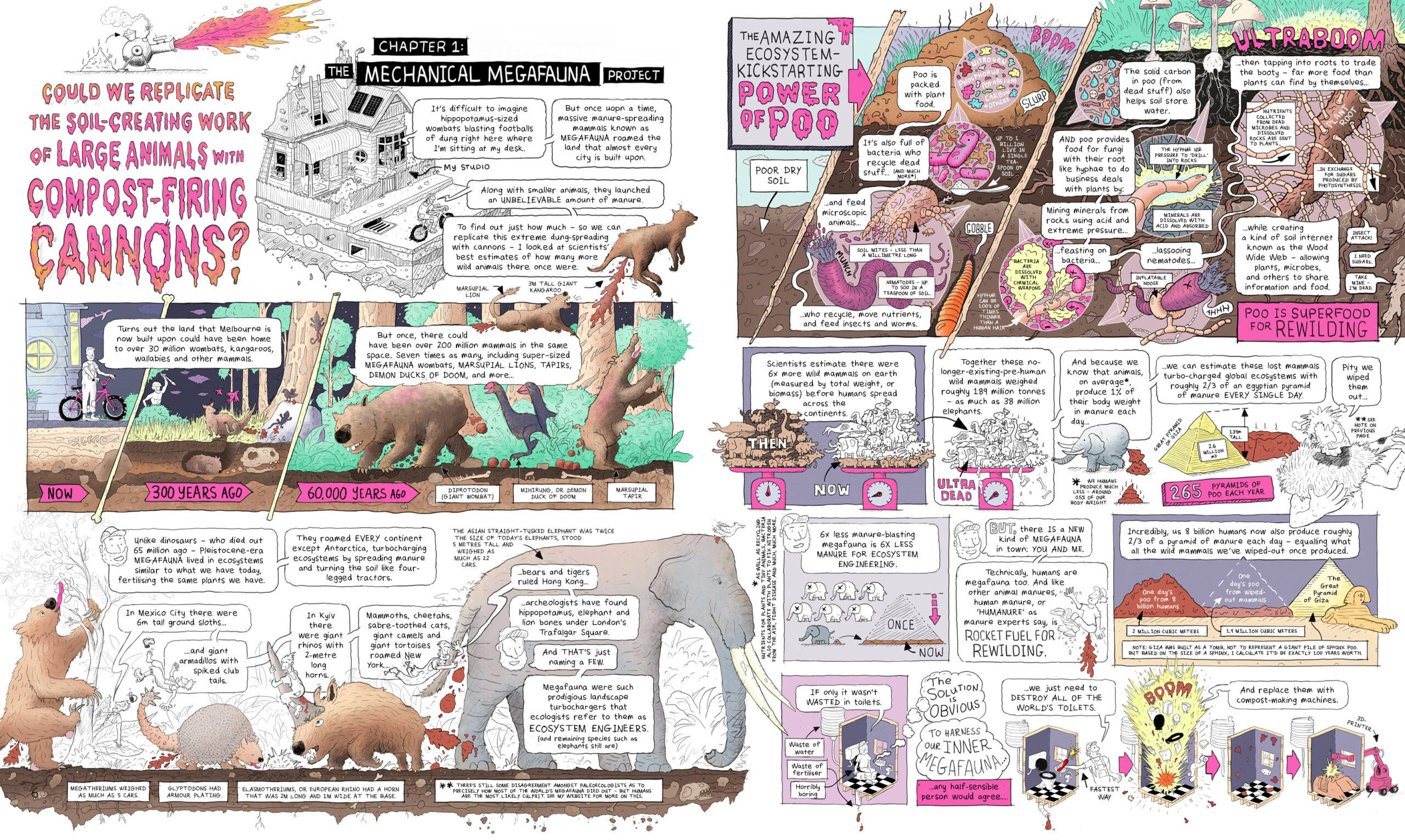

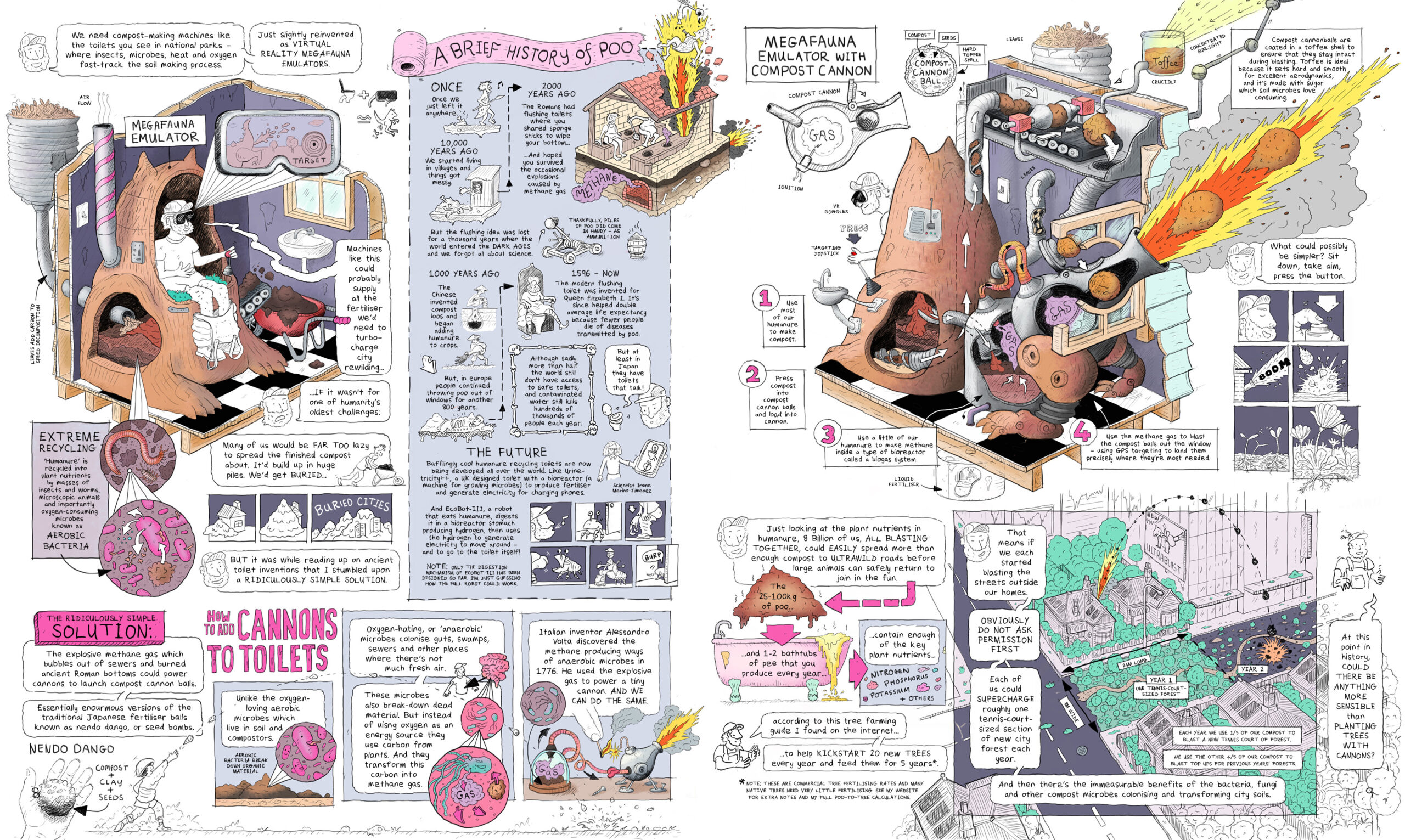

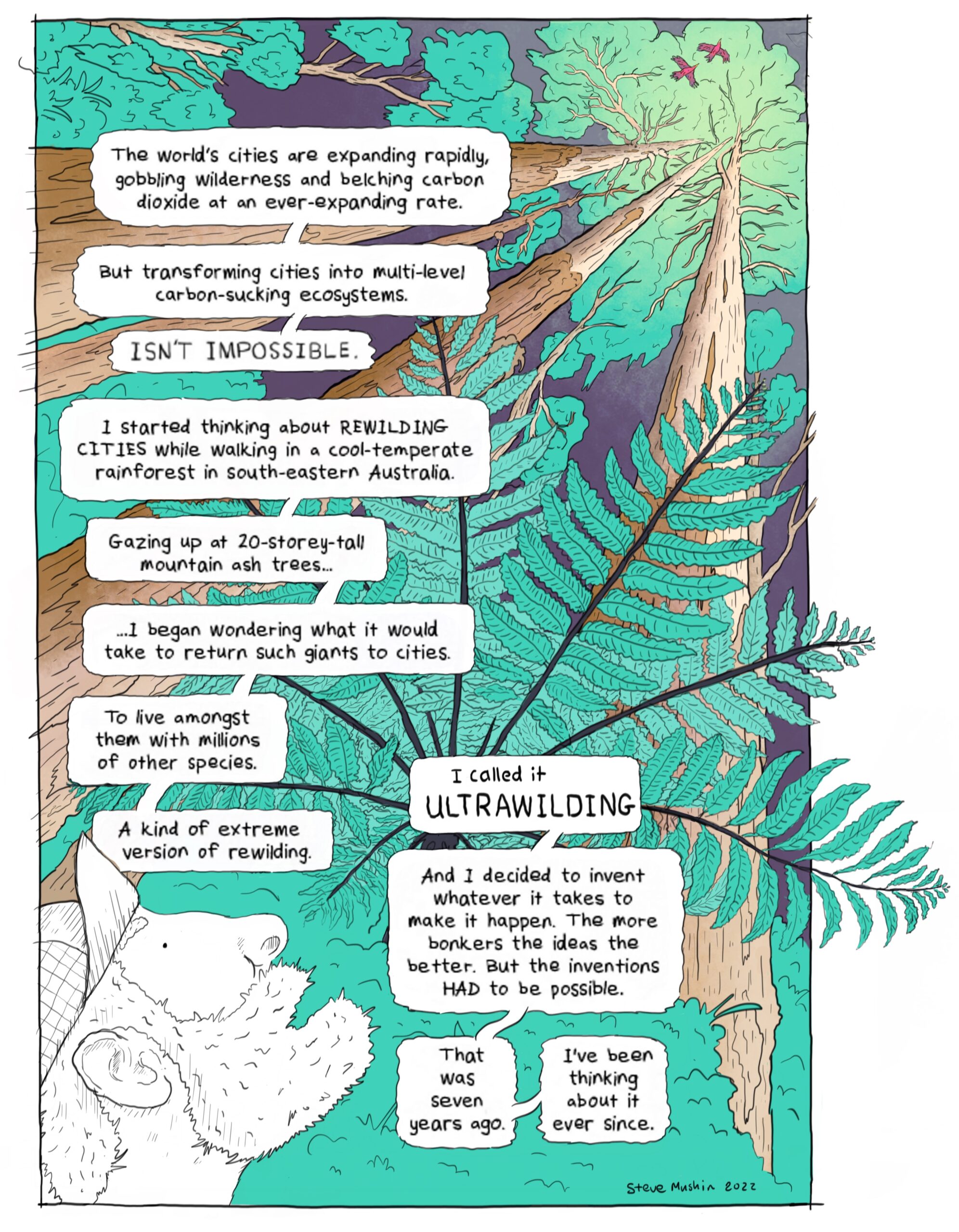

The book began about 15 years ago while I was working on engineering research at CERES Environmental Park in Australia. A small team of us designers, engineers, scientists and teachers received about a million dollars in funding to develop demonstration prototypes for technologies which could help Melbourne become a zero emissions city. We built a modular hydroponic farm, a large-scale worm composting system, a solar concentrating dish, greywater filtration systems and a biogas reactor. And it was while working on these projects that I began developing the speculative engineering ideas in Ultrawild.

I became increasingly terrified about the lack of global climate change action…

After CERES I developed a series of projects for a touring exhibition of future thinking with the Australian Centre For Design, called CUSP. That led to a solo exhibition of ideas for urban farming at Spiral Gallery in Tokyo, called Farming Tokyo. And when I returned from Japan, Allen & Unwin asked me to produce a book of the ideas, giving me one year to do it.

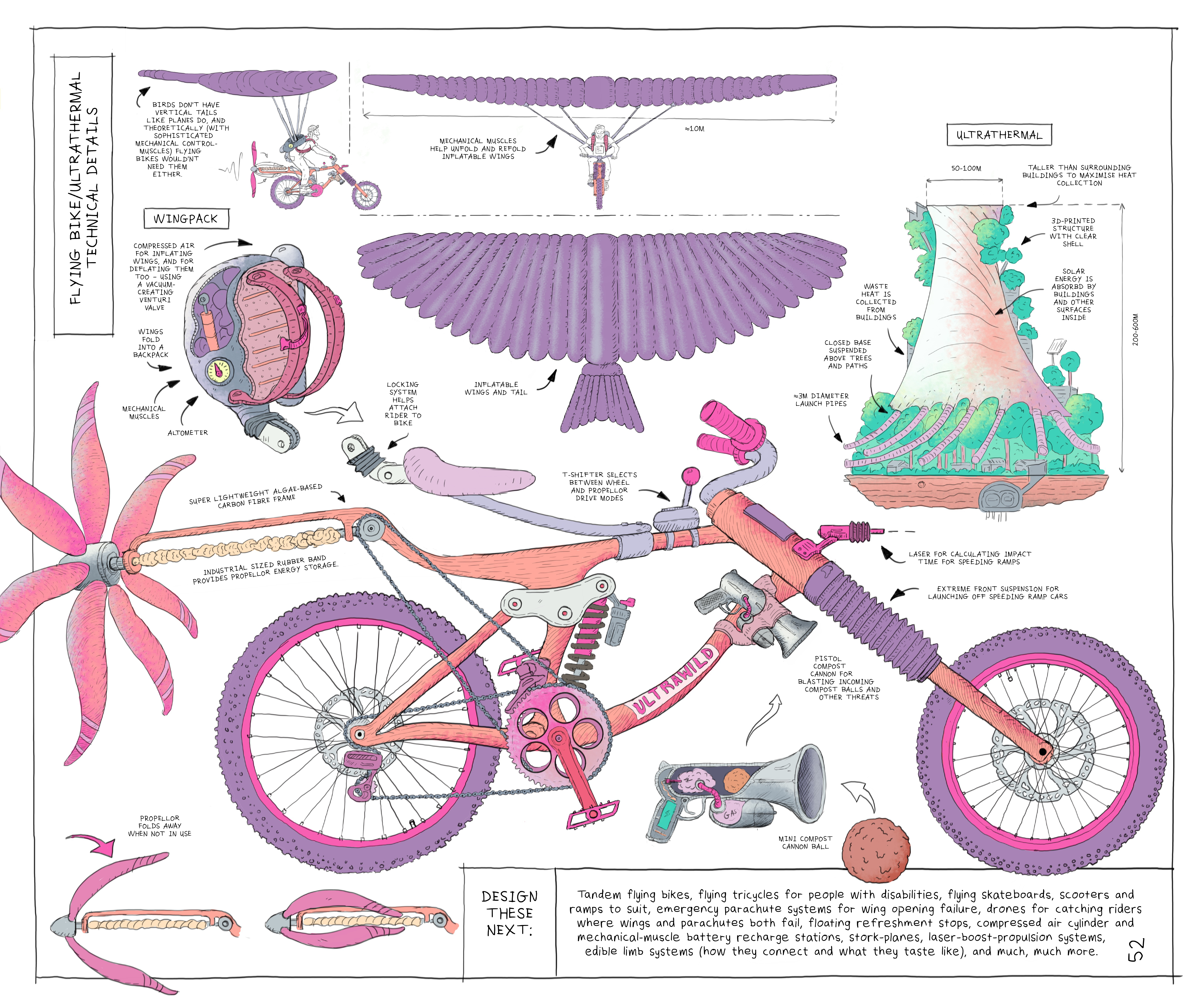

Ultrawild ended up taking seven years! This was partly because I massively underestimated what it takes to make a graphic book. But also because of the complexity of the projects. Every invention needed to be possible, and so involved collaboration with scientists and engineers for technical advice. And all of the ideas needed to work together to create both an engaging narrative, and a vision for future cities that was possible, appealing, and funny too. I initially imagined the book involving a few dozen sketches and ten ideas. It ended up containing just over 1,000 drawings and 100 unique inventions. Luckily, Allen & Unwin were endlessly wonderful, patient, wise and supportive on this journey.

I absolutely love that your calculations for the number crunching in Ultrawild are freely available online. Aside from my personal love for spreadsheets, what a great resource for the curious, nerdy, and aspiring inventors of the world, and an endorsement for the idea of open access data. How do you hope this information will be used?

Ultrawild is all about pushing engineering and urban rewilding ideas to the extreme, whilst still being actually scientifically possible. So it was important from the start to give readers the ability to download my calculations and notes—as is the done thing for scientific papers. As far as I’m aware, Ultrawild is the first kids’ science and engineering book where this is offered. For anyone interested, head to www.ultrawild.org. My hope is that schools (and really cool nerdy people) use the data to help them with their own design thought experiments.

You’re an industrial designer and artist and have worked on science-based adventure playgrounds, large-scale megafauna sculptures, among other things. But you’re also a science communicator—who do you work with and what messages do you impart?

My real world design projects often involve inventing large hypothetical machines for science-based playgrounds and exhibitions (such as my bus-size mechanical millipede that pulverises roads and plants trees. Or the seed-scattering flying machine I’m working on right now). And it is through these projects that I get to work on fun science communication signage to explain engineering principles, and how my inventions could transform cities. The goal: get people really, really, really excited about science, design, and reinventing the world!

Many of us are jaded by what feel like hopeless causes: reversing or mitigating the effects of climate change and protecting biodiversity. Audacious ideas are exciting and fun, but how do you envisage buy-in for large scale rewilding projects at a local council, governmental, and international levels for uptaking actual change?

Rewilding is already happening, all around the world. Vast rewilding projects are sucking down carbon, boosting biodiversity and showing that ‘nature-based climate solutions’ are doable, cheap and powerful. And ultrawilding—a term I invented for high tech urban rewilding—is already happening, too. In fact, I argue that Aotearoa – with our Predator Free projects and dozens of tech startups developing technologies to remove pests and help native animals return to cities like AI smart traps and forest planting drones – actually leads the world in ultrawilding. Cool international examples of ultrawilding are the massive Supertree habitats in Singapore, the vertical forest skyscrapers in Milan and China, the removal of a city motorway to return the Cheonggyecheon stream in central Seoul, bird bricks in UK buildings, 3D printed owl hollows produced by the University of Melbourne, and a lizard garden on the roof of a Zurich railway station.

It was important to you that Ultrawild’s approach was playful and fun, in order to excite readers about the concept of rewilding, while also acknowledging some of the depressing reality of human impacts on the earth. How did you come to striking that balance and retaining a sense of hope for our younger generations?

Initially Ultrawild was ALL positive. It was a book of wild and funny ideas that could help reverse climate change. But as the years went by, I became increasingly terrified about the lack of global climate change action. And one day in 2019, while writing in 40 degree heat in Melbourne, under skies darkened from vast fires in Sydney, I suddenly felt that I could no longer produce a book that was purely humorous and positive. I realised then that I had to include my personal journey navigating feelings around climate change. That was when I wrote the book’s black ‘inner most cave’ pages, and what led me to include an epilogue exploring real world technologies which give me hope that we can indeed still reverse climate change.

You’ve talked about brain research and how playful thinking is important for creativity, and Ultrawild is certainly an exercise in playful and creative thinking. What advice would you give to teachers, parents, and other educators about outside-the-box thinking and action? And how can we rewild audaciously in our own backyards?

In Ultrawild I describe how the latest brain research on creativity suggests creative thinking can be strengthened with wild and outrageous thinking exercises, or ‘thought experiments’. Like mental yoga for creativity! And because we all know that to beat climate change we need to re-invent almost everything about cities. And so it follows that we need to invest massively in creative engineering and design. We can conclude that having outrageous design ideas to boost creative thinking is an extremely sensible and valuable thing to do.

Quite simply, for our planet to survive, schools must prioritise creative thinking at the same level as maths and English. I’d go further and say that schooling should be entirely based around exploring big creative thought experiments—for brain boosting power, and simply for the joy of it.

…schooling should be entirely based around exploring big creative thought experiments

My suggestion to schools—to anyone—is to do regular exercises with:

1. Real-world design problems where maximum outgoingness is encouraged. So, maximum hypothetical design thinking to promote thinking outside the square.

2. Hands-on nature-based design projects. So, building bug hotels, garden beds, native animal habitats, etc—anything which connects us to ecosystems.

I’m currently touring Aotearoa, running Ultrawild Design Workshops with primary and high schools. For teachers interested, the awesome literacy advocacy project ReadNZ can help subsidise my visits.

And finally, is it true that your mum wrote the famous kiwi kids’ song, Fish and Chips?

Yes! When I was 12 old, my beautiful and endlessly creative mum, Claudia Mushin, wrote the famous song, Fish and Chips, in response to my eagerness for that meal. It was published in a book called Kiwi Kidsongs 3 in 1992. The song has since had a colourful history – at one stage the New Zealand government tried to ban it (citing its unhealthy eating message). People often don’t believe me when I tell them my mum wrote Fish and Chips. So for anyone who’s curious, here’s the National Library record for the song’s original publication and copyright.

Ultrawild: An Audacious Plan to Rewild Every City on Earth

By Steve Mushin

Published by Allen & Unwin

RRP $37.99

Linda Jane is a writer of picture books, poetry, essays and science. Her background is varied, including work in ecology, environmental education, summer camps, and a community newspaper. She is Singaporean-Pākehā, queer, and loves leaping into cold bodies of water. She was previously lead editor for The Sapling.