Kura Rutherford describes her role as a Steiner school librarian, and how the holistic curriculum means the school library is able to support the wellbeing of the students in an environment where there is room for it all—the scientific, practical, socio-psychological, intellectual, cultural, but also the intangible and the magical.

Sometimes I try to walk through our school, Michael Park School in Ellerslie, with the eyes of a newcomer. I see fresh blossoms on the orchard trees, hand-dyed wool hanging out to dry, children making fire from flint in the outdoor classroom pavilion, a new batch of bowls in the clay room. I feel as if I’ve walked out of my own everyday life into another world; a little pocket of beauty, and a reminder that sometimes it’s the simple things that bring the most happiness.

The Steiner curriculum is often described as a healing education, and as an ex-nurse and an English literature graduate, I am really grateful for the opportunity to bring my studies together in the school library; using literature and the library to support the education’s overall goals of helping students develop resilience, optimism and resources to meet life’s challenges.

I’ve been a school librarian in two Steiner school libraries, Taikura Rudolf Steiner School in Hawke’s Bay and here at Michael Park School. In both of these schools the library has always been a calm, beautiful space, purposefully easy on the senses. You won’t find junior students on computers, or experience rowdy lunchtimes, but it is still full of life; student librarians busy drawing book posters or shelving books, younger students taking turns to read to each other, older students playing chess, parents reading to their children at whānau hour, and on a special occasion, even a child knitting! My role as kaitiaki of this space means I work directly with the younger classes, with the support of the teachers. I purchase and process books, I set up community outreach as well as services and programmes in the library (like National Library book boxes and the student librarian programme), I network within the broader library community, and I collect and develop resources to support the unique curriculum.

The Steiner curriculum is often described as a healing education

The Steiner curriculum centres around yearly themes taught through main lessons by a teacher who ideally travels through the junior years with the class. The main lesson is a 3-6 week block of two hours a morning where a particular subject is studied in depth. The topics vary significantly across any given year, covering anything from chemistry to poetry to building, but are all part of a whole year particularly tailored to the developmental stage of a class. Alongside this, there are a wide variety of specialist subjects, many of these practical. A class may be working on a play, gardening, singing waiata, or learning to use stilts.

The library curriculum mirrors the overarching theme of the year’s teaching as much as possible. In Class 4 (Year 5), for instance, where one of the curriculum themes involves supporting students to place themselves in time and space, the library curriculum looks at famous authors from around the world, with a special focus on New Zealand authors. Last year, we had a class-wide reading challenge where the students aimed to read as many classics as possible, which we visually charted on the wall by placing a coloured cardboard pebble on the path for each book read, attempting to get as far around the library as possible. The class kept up the impetus for the challenge for the entire year and made their way through a huge number of classics. In the same year, we also often have a book-share day when I tell them a story of Margaret Mahy’s life, and children will bring in one of her books from home. To finish off this curriculum focus, I ask the students to interview someone in their family about their favourite book from childhood, which they then write up into a report. In our final lesson of the year, we make an occasion of sharing the reports in library time.

Steiner education places real value on the role of stories to help build health, empathy and understanding, as well as to help spark creativity and inspiration. This means that from kindergarten through to Class 12 (Year 13), whole main lesson blocks can be developed around a particular story, and stories are introduced right across the curriculum subjects.

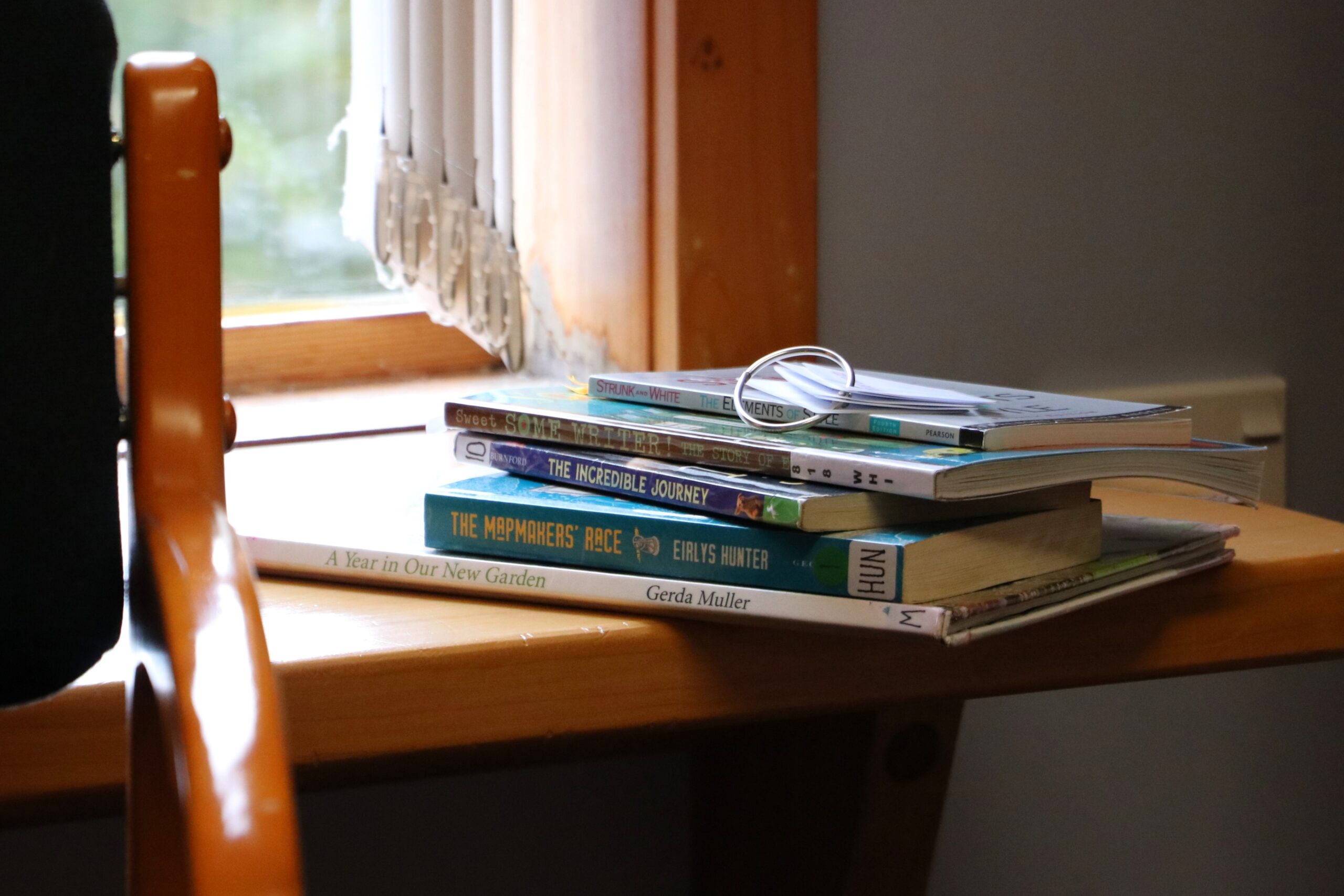

This emphasis on storytelling means the children build an intrinsic love for stories. We start every library session with story time, and there is nothing quite like the feeling when the room is totally still and a whole class is spellbound by a story. I have titles I read and reread to different year groups, because the books never lose their magic. When I read Nanny Mihi and the Rainbow by Melanie Drewery, the children’s eyes light up and they tell me all about the puppet show version they had at kindergarten. The Mapmakers’ Race by Eirlys Hunter is my favourite read-aloud, and every class I’ve read it to has loved it. Whether it is finding examples of ‘show, don’t tell’, noticing the word pictures Hunter creates, or searching for clues of where the book is set (the jury is still out on that one)—it’s a brilliant ‘teaching’ book. The Lost Words by Robert Macfarlane often sneaks its way into story time too and poetry in general is popular. A focus on the therapeutic value of storytelling influences the books we buy too.

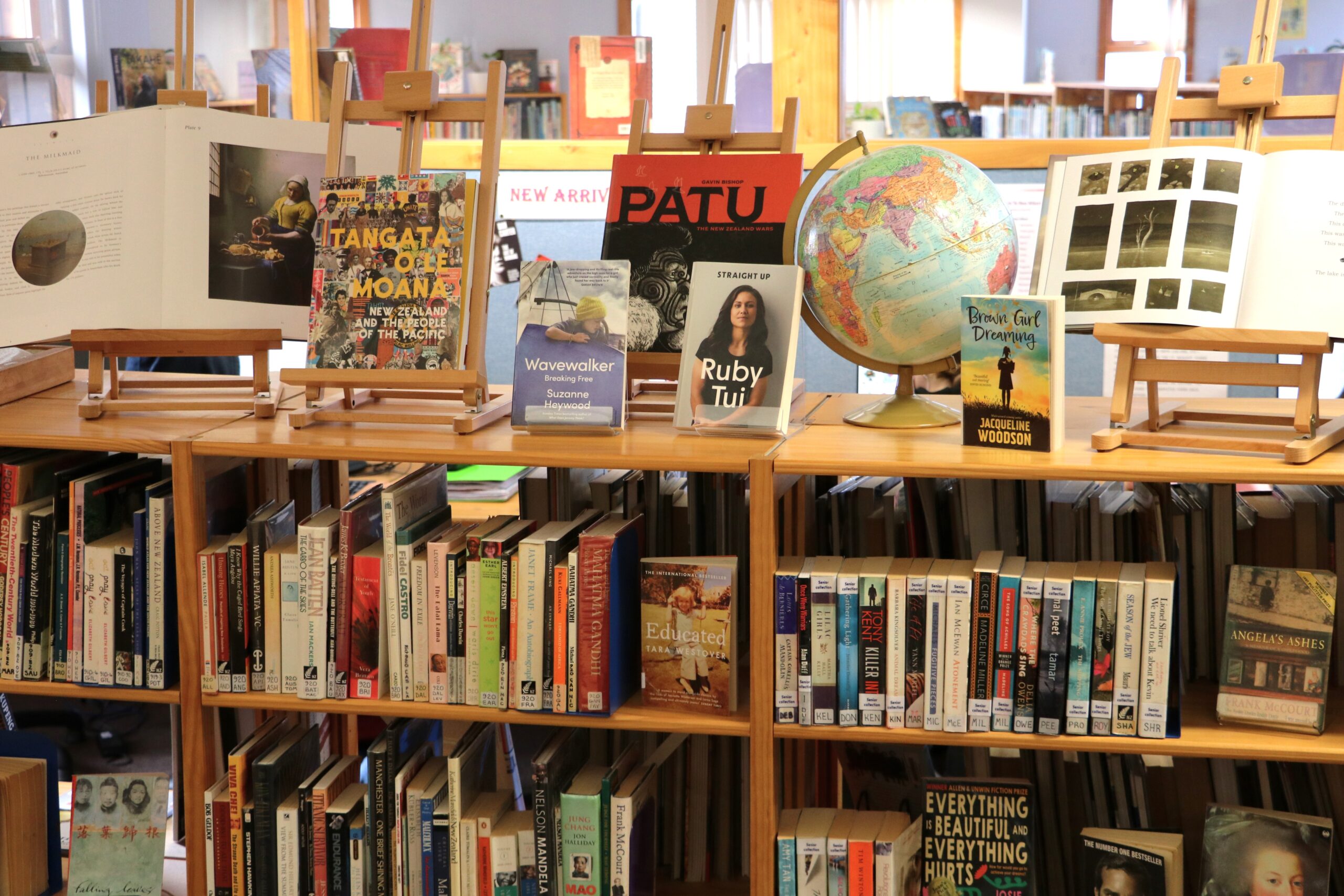

Journeys where challenges are faced and overcome are recurring themes throughout our library collection. We look out for exceptional biographies from around the world: Lion by Saroo Brierley, Educated by Tara Westover, and Trevor Noah’s Born a Crime have all been read out loud to our seniors as part of a main lesson. Fiction with a sense of warmth, emotional depth, and genuine hopefulness goes to the top of the ‘to buy’ list, as do books that portray something illuminating about the human experience. We are always on the hunt for picture books with a warm, positive message, a sense of wonder, and vibrant, beautiful art.

Book buying is also influenced by the constant work being done nationally to make sure the curriculum really fits here in present-day Aotearoa. I’m acutely aware of how much it enhances our students’ wellbeing to feel connected to where they stand in the world, and I am always on the lookout for ways to bring te reo me ōna tikanga Māori, and the diverse cultural landscape of Tāmaki Makaurau, into the curriculum through resources that enhance the learning in meaningful, authentic ways.

Books like Stacey Morrison’s Kia Kaha are a staple in our library because you can tie in a biography with a lesson topic—Hekenukumai Busby’s biography is often used in a Pacific voyaging focus for instance, and Dame Naida Glavish was recently used during a Renaissance main lesson that tied in Māori language revitalisation. Books like Cuz by Liz Van Der Laarse, Charlie Tangaroa and the Creature from the Sea by T.K. Roxborogh, and The Tooth by Des Hunt have all been popular fiction to support a main lesson, and Andre Ngāpō’s Rongoā Māori in the school journal has been used to introduce the Class 5 botany lesson. It’s an exciting time in New Zealand publishing, and I love that every month there seems to be a new book coming out that adds to the growing understanding that all our tamariki need to see themselves in our published stories.

Years of collecting and book hunting means that now the library collection is an absolute treasure trove of beautiful stories from Aotearoa and around the world. Michael Park School library, like Taikura, was built up from scratch by a committed, hardworking librarian, and I have been very lucky in both my roles to have followed on from these two legendary librarians. Both librarians had a vision of what a library could offer students and, over 30 years respectively, they went about bringing that vision to life, with the support of amazing leadership teams, boards, teachers and generous donors, who all valued the role of the library. I know it is a real privilege to have this widespread support towards resourcing our library, but I wish it for every child in Aotearoa. Every day I see how much the students benefit from this space, and I also see our issue rates rise annually—libraries and books are not going out of fashion, so long as we all put in the mahi to help them thrive.

Libraries and books are not going out of fashion, so long as we all put in the mahi to help them thrive.

I am thankful for being able to work in an environment where a holistic picture of wellbeing is visible in all parts of the school, and also grateful that it is a big part of my job to help this grow. I’ve seen enough classes make their way through the school to know how well the schooling sets students up to live fulfilling, creative, wholehearted lives, and I love that stories and storytelling are such a central part of what makes the school journey special.

Kura Rutherford

Kura Rutherford (Te Rārawa, Ngāpuhi) is a school librarian, writer and editor, who lives in Tāmaki Makaurau. She grew up in Hokianga and Grey Lynn, before moving to Hawke’s Bay for 20 years with her husband, Dominic, to bring up their three daughters. She worked for 10 years in public libraries in customer service and community roles before becoming the sole charge school librarian at Taikura Rudolf Steiner School in Hastings. Now having returned to Tāmaki with her family, she works in the same role at Michael Park School in Ellerslie. She has been connected to Steiner education since she was 23 when she and her husband worked for a year at Hōhepa Farm in Hawke’s Bay, and all three daughters have attended Steiner schools. Kura’s writing focus is on health, education and literature, and she has written for The Sapling, Good magazine, EBSCO databases, Magpies magazine, and craft magazine Extracurricular. She has a special interest in supporting organisations in their te reo Māori strategic planning and development aspirations.