Storylines Children’s Literature Foundation has given awards for local children’s literature since 2000, named for some of our most distinguished authors, both living and dead. All images below are courtesy of Crissi Blair.

This is the first time I have made it up to Auckland for the presentation of the Storylines Awards, this year incorporating the Joy Cowley Award, the Tom Fitzgibbon Award, the Gavin Bishop Award for Illustration, and the Gaelyn Gordon Award for a Best-Loved Book – and, of course, the presentation of the Margaret Mahy Medal (est 1991) and the associated Lecture, this year given by recipient Des Hunt. The Margaret Mahy Medal is our local equivalent to the Hans Christian Andersen Medal, honouring our best-known, beloved tellers of tales. (Tessa Duder has written a piece for The Sapling about each of these awards, to be online soon.)

The day opened with a Lifetime Membership of Storylines being awarded to the extremely deserving Libby Limbrick, for her 30 years of service with Storylines NZ/Children’s Literature Foundation of NZ. This is only the seventh Life Membership ever awarded. Tessa Duder had the excellent job of awarding it to her friend of 55 years, met by a standing ovation for Libby as everybody in the room knew just how well she has led Storylines in pursuing their aims over the years.

There was a murmur of surprise as no overall prize was given this year for the Joy Cowley Award for a picture book text. Penny Scown noted that Kyle Mewburn’s 2006 book Kiss Kiss, Yuck Yuck is still the most successful Joy Cowley Award-winner to date – there are over 160,000 copies now in circulation. Penny noted that of the 176 manuscripts submitted, 90% of them were rhyming texts, yet rhyme is extremely hard to do well and not essential for a successful picture book text. If you wish to enter next year’s award, there are tips on Picture Book writing from Joy Cowley on the Storylines website.

… rhyme is extremely hard to do well and not essential for a successful picture book text.

One of my favourite of the Storylines Awards is the Tom Fitzgibbon Award for an unpublished novel. This frequently pushes up writers to watch: Leonie Agnew, for instance, is now an established and prize-winning novelist; and 2013 winner Juliet Jacka has recently published a junior fiction series with Penguin Random House.

The prize for 2017 went to Christine Walker, for The Short but Brilliant Career of Lucas Weed, which Rob Southam, on behalf of Lynette Evans, noted was ‘fast-paced, with well-developed dialogue’ – and an irresistible title. Christine is a Community Librarian, a lifelong reader and ‘a great believer in the difference books can make to a life.’ She completed her manuscript in the final eight weeks before it was due, by ‘coming home and writing 1,000 words a night’ – a feat that made all the experienced authors in the room sigh in envy. Her dream was always to be first a librarian, then an author.

We have already published an interview with the prodigious 19-year-old Lael Chisholm, who won the Gavin Bishop Award for Illustration. There were seven other finalists, all female.

The legendary Pamela Allen was the recipient of the Gaelyn Gordon Award for a Much-Loved Book. This award is for a book that has stood the test of time, but never received any awards on its publication. Mr McGee was published in 1986, and was only her fifth book. She said, ‘I gave this book to three-year-old Jessie Maynard, and a few months later was invited to read to her and a friend at bedtime. They knew every word, and joined in at the end of each sentence. It was extremely gratifying.’ It was wonderful to see Pamela out, as she has been pulling back from public life since I’ve been in the kids’ lit world.

It was then time to see the winners of the Storylines Notable Books Awards file up: there were a few under-represented categories, particularly young adult fiction, but Crissi Blair had to do a bit of fancy photographer bunching to get all of the Picture Book winners in the frame.

The final duty for the first half of the meeting was a launch for Anne Kayes, who won last year’s Tom Fitzgibbon award for Tui Street Tales. The cake looked marvellous.

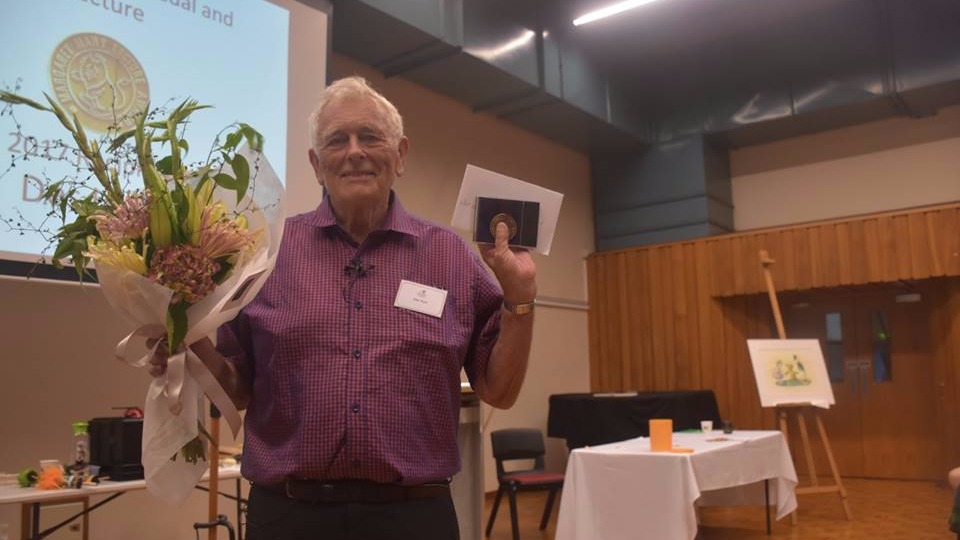

Des Hunt’s Margaret Mahy Lecture

I have counted Des Hunt as a friend since taking him, Kyle Mewburn and Fifi Colston on a the sky is the limit when you read tour to the West Coast (my home ground) in 2008. I was lucky enough during that tour to sit in on some of Des’s sessions with primary school and intermediate-aged kids. His box of tricks and toys is almost equal to those of any street magician; and he tells stories and write books to boot. Seeing him take the stage for this prestigious lecture was wonderful.

Des began by telling us about his first case of stage fright in years, at a True Stories Told Live event run by the Book Council at the Hamilton Gardens Art Festival. He realised later what his problem was: when he goes to a school, he creates his own environment with his props – like Margaret Mahy did with her wild wigs, badges and scarves. Up there that day, he had nothing but himself to rely on. So he decided to create a tokotoko – something easy to carry with him on visits, inspired by a visit to a marae when he was a student.

… he creates his own environment with his props – like Margaret Mahy did with her wild wigs, badges and scarves.

Throughout the lecture, he mounted totems on his tokotoko to explain parts of his life as a storyteller. Some were expected, predicted by the themes in his books: a gecko, for his first published novel; a frog, for another book; a beautiful poppy, for his book out next year; a kiwi, for his nature focus; a kiwi and pukeko fighting for ascendancy as New Zealand’s number one bird… and then there were the less predictable totems. A cow, given to him by his house captains at Rosehill College after 30 years’ service. And an empty glass drink bottle.

This totem saw Des spin a story of his childhood in Palmerston North. Aged 12, he and his mate had gone adventuring (on their bikes, smoking cigarettes) to an old, abandoned-looking house at the edge of town. There were two sheds on the property: one locked tight, the other slightly ajar. So they went in. It was an old carriage house, complete with carriages. Knowing carriage lights often had Carbide in them (Des was a know-all with a special interest in science), he went hunting around for some to make stink bombs at school. But, instead, he found empty glass bottles, which you could trade in at the local shop for money: four would get you enough cash for a ten-pack of cigarettes.

By the time he got home, the cops were waiting for him. They knew he had bottles – the neighbour of the house had dobbed them in – and the owner thought he’d left strychnine in one. Not one that he had, but Des was aggrieved he hadn’t even got home before they were onto him. Pondering that now, he realises that it meant a caring community looking out for him. Everybody knew everybody’s business. They kept an eye out. Des embraces this in his books: his characters have absolute freedom of movement and expression, because they are within the safety of the village.

… his characters have absolute freedom of movement and expression, because they are within the safety of the village.

Des’s first book wasn’t actually a novel: he started out writing science resource books for Physics and Chemistry, back in 1972. He explained that thanks to a terrible teacher in English, he never got into writing at school – the teacher he co-wrote his resources with had to teach him how to write clearly.

Des’s books bring science and the environment into action stories. His idea was to write for boys specifically, but it wasn’t long until he realised his audience were both boys and girls: and his books worked very well as read-alouds. This forced him to be strict with himself in terms of story structure. His chapters are all pretty close to being the same length. Each of them can be taken as a capsule story, as well as giving a ‘what comes next’ feeling to the reader; and every story has a clear beginning, middle and end.

Des talked a little about how much kids – all kids, no matter the age – enjoy being read to. He spent 90 minutes with an assembly of Year 10s, and he’d run out of all of his tricks with 15 minutes to spare: the teacher suggested reading to them. So he did, and the act of listening to the same story settled them, gave them a shared experience.

‘Start with a stink, end with a bang’

Des used the rule ‘Start with a stink, end with a bang’ in his science classes while teaching; he uses it in his school visits, too. And he realised that this was the story arc. He had been using the story arc to teach classes for as long as he was a teacher. Another totem read ‘imagination of a child and wisdom of an adult’ – another useful thing to keep in mind when writing for children.

The final totem was one I always associate with Des: a bomb with a radioactive symbol on the front, for Cool Nukes. With a bit of mouth freshener, this (eventually) delivered his bang.

I think by the end of the lecture, the crowd were in agreement: Des Hunt was a very worthy recipient of the Margaret Mahy Medal and Lecture. Thank you to Libby Limbrick and the Storylines committee for putting on a great set of awards, with a wonderful talk at the end.

Here are a few Des Hunt books to check out with your family:

Sunken Forest (Scholastic NZ) $18.00 Buy Now

Deadly Feathers (Torea Press) $20.00 Buy Now

Cool Nukes (Scholastic NZ) $18.00 Buy Now

Project Huia (Scholastic NZ) $18.00 Buy Now

Sarah Forster has worked in the New Zealand book industry for 15 years, in roles promoting Aotearoa’s best authors and books. She has a Diploma in Publishing from Whitireia Polytechnic, and a BA (Hons) in History and Philosophy from the University of Otago. She was born in Winton, grew up in Westport, and lives in Wellington. She was a judge of the New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults in 2017. Her day job is as a Senior Communications Advisor—Content for Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.