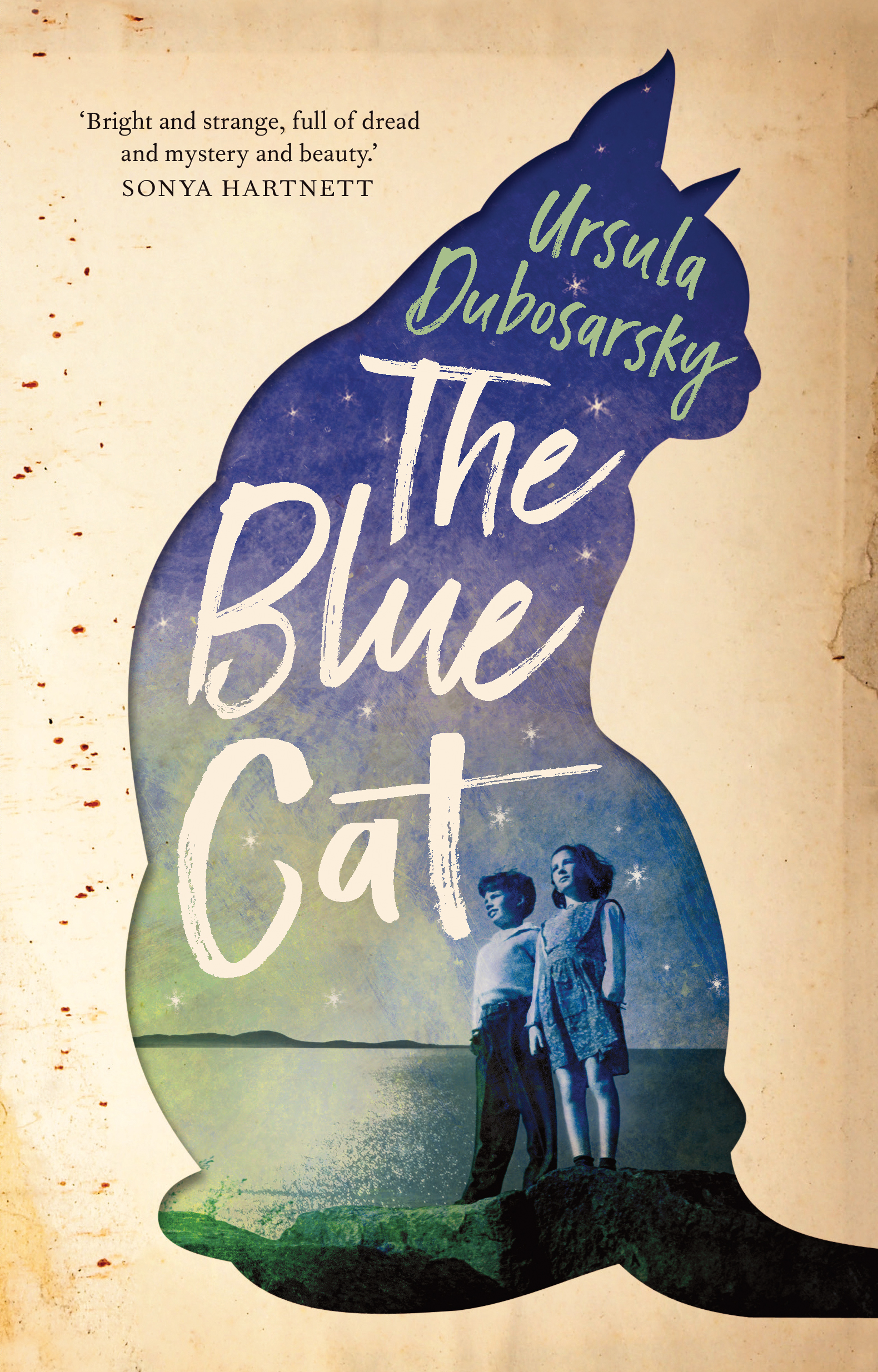

Our editor Jane Arthur comes out from behind the curtain to interview the multi-accoladed Australian children’s writer Ursula Dubosarsky, whose latest novel The Blue Cat is out now.

Ursula Dubosarsky made me an evangelist at first read. It was The Red Shoe, and it was like nothing else I’d read in children’s literature. It’s ‘about’ a lot of things, including life in mid-century Australia and the threat/romance of Communist spies, hydrogen bombs and polio, but it’s also hypnotic and strange. Then I read The Golden Day, about ‘the confusion of childhood, the strangeness of things half-glimpsed and only partly understood’ (Early Childhood Council), which I loved. The Wall Street Journal called it a ‘chilling, elegant, atmospheric novel’, which is spot-on. It’s her atmospheres that make her novels stand apart. In those books, it’s almost as if more is happening between the lines than on the page, which is equally disconcerting and addictive to a reader – to me, at least. I’ve always been intrigued by the unsaid, by inferences and vibes and things below the surface. The unsaid is what Ursula Dubosarsky does so well.

She’s a writer’s writer, and a quiet child’s writer. Though she’s written dozens of books, including funny picture books and chapter books about guinea pig detectives, her ‘middle-grade’ novels have me shouting loudest on my soapbox, her books for ages (approximately, of course; I’m in my thirties) nine to 14. It’s that time when you’re complex and deep-thinking and beginning to notice your own oddness in the world, but without the full extent of puberty’s torment.

Her protagonists are watchful; they question deeply but are also naive. Though maybe naive is harsh – they are, after all, children. But they’re children whose worlds are opening up more and more each day because of wars and crimes and scandals, and simply because they’re growing older. For a reader, it’s compelling: mostly, we know just that bit more than they do – except for when we don’t.

In her latest novel, The Blue Cat, Dubosarsky gives us young Columba, dreamy, caring and mildly gullible. It’s the middle of World War Two, but Columba lives in Australia so we can’t blame her for not really knowing what or where ‘You-rope’ is. She knows it’s where Ellery, the silent new boy at school, is from. She’s drawn to him not because of the rumours (is he a Nazi? A Jew? What is a Jew? Is his mum dead? And if so, how did she die?) but in spite of them. Theirs is a beautiful relationship, made up of looks and tentative smiles, with silence and an innate understanding of each other, somehow.

But while we can think to ourselves, ‘Oh, silly girl, it’s Europe,’ we can’t claim we know the mystery that is Ellery. We don’t know how much English he understands, or anything at all about his life before he arrived in Australia, or what of the war he experienced. Or where his mum is. As readers, we’re not more clever than the girl; we are the girl.

The Blue Cat is about mysteries multiplying as your world expands; people (and cats) can appear and disappear without explanation. They’re just something that happens, though they can change you a bit along the way. The book is also about mysteries not being solved and endings not being tidy. It’s about the instinct to be afraid of the unknown, which in the book includes God and the Japanese, and learning to work out which things deserve our fear. It’s beautifully written, at once lyrical and plain-speaking, and captures pre-pubescent wonder so well:

‘Why didn’t it rain? The sun was so bright. Everyone knew that if you looked directly at the sun your eyes would burn up and go blind. I covered my eyes with my fingers and peeped through. The light lit up the blood of my hand so it turned a glowing pink and there was the sun, a shadow of blood, moving soundlessly through my fingers on its way across the sky, like one of the ships in the harbour sailing off to war.’

I spoke with Ursula Dubosarsky about The Blue Cat and her writing process.

Jane Arthur: There’s a thread through many of your novels of the impact – both immediate and eventual – of World War Two on Australian life, which is emphasised by the inclusion of facsimile documents from the time (air raid information, newspaper clippings, photographs). What is it about the War for you?

Ursula Dubosarsky: Both my parents grew up in Sydney during World War Two, so the stories they told of their childhoods have stayed with me. Other things, too. In 1985 I spent a year on a kibbutz in Israel (I’m not Jewish, just went travelling), and I learned Hebrew from a man called Yehuda Artzi, who migrated to then-Palestine from Munich in the late 1930s.

I suppose it was in those small classes that I came face-to-face with certain facts of history in a personal way, things I thought I already knew, that everybody knew, but actually I didn’t really know. I suppose I’ve never gotten over it. I often think about something Jean Améry, who wrote a short book about his time in Auschwitz, said: ‘I had no clarity when I was writing this little book. I do not have it today, and I hope that I never will.’

I came face-to-face with certain facts of history in a personal way, things I thought I already knew, that everybody knew, but actually I didn’t really know.

As for the documents and photographs – for me they are a kind of collage, accumulated bits and pieces that help make up the picture as a whole. I guess you could describe The Blue Cat almost as a ‘montage novel’, something like the montage cinema of Russian director Sergei Eisenstein. He wrote in 1925 that ‘the essence of cinema does not lie in the images, but in the relation between the images’ and certainly the images and the clippings and the other documents in The Blue Cat take on a different meaning in the context of the story and the specific moment in the story at which they are placed. They are both a commentary on the story, and also part of the story.

J: Your website has a lot of expanded information about the factual background of a number of your books. Is it important for you to write books that educate their readers as well as entertain and captivate?

U: Well, I feel novels should just be read for what is between the covers, that it should all be there, in the sense of the emotional content that forms the meaning of the book. I put the information on the website for those curious readers who want to know more about how a book comes to be what it is, and of course for students and teachers.

It’s for myself, too. I enjoy the process, as most of the time the things that end up on my website are not on the top of my mind at all when I’m writing. It’s more that I sit down afterwards and think to myself, ‘What was THAT all about, Ursula?’ Then I trace the thoughts back. A bit like when you wake up from a dream …

J: The Blue Cat has a great cast of characters. They’re each totally individual and convincing, from gentle Columba herself, to her know-it-all whirlwind of a classmate, Hilda, to the American soldier they meet at the pool who may or may not be deserting, to the charming old sisters next door with secrets of their own. How do characters come to you?

U: Sadly I’m completely shocking at describing how I create characters! When I teach writing, this is the part for me that is beyond explanation. I often say to children that writing a story is like playing with your toys, except the toys are in your head instead of your hand. The personality, the voice, the behaviour of each character appears as you play (write) in a way that seems as natural as breathing. And just as when you play with toys, for some reason one character becomes more dominant than the other. Perhaps you just like playing with it more, I don’t know.

… writing a story is like playing with your toys, except the toys are in your head instead of your hand.

While we’re on the subject, I have to say I’m also hopeless at physical appearances of characters. They’re just shadowy presences in my mind, physically anyway, but with very distinct souls.

J: There are so many secrets and mysteries in the book – Ellery’s past (and future); quiet, nervous Miss Marguerite; the cat – that are never resolved. I love that you don’t feel the need to make everything tidy for your young readers. But … do you know the answers to these mysteries? Do you have to know in order to write about them?

U: It’s true, all my books, including my picture books, are full of secrets and mysteries. I think sometimes I’m the most mystified of all! It’s not on purpose, I don’t set out to deliberately mystify. I just start a story and follow it along its path, and like the reader, I’m on a quest to understand the meaning of things and uncover the truth. But somehow the door is always still open at the end. It might slam shut for a moment in a sudden wind, but then it swings open again with a faint creak. A palm reader in King’s Cross told me thirty years ago that I came from a ‘hidden culture’. Hmm.

I’m always intrigued and impressed by the ingenious solutions that readers come up with, often very plausible.

I don’t set out to deliberately mystify. I just start a story and follow it along its path …

J: Speaking of mysteries (and even though I claim to be fine with things being unanswered): what is the significance of the ownerless cat which appears and disappears throughout the book?

U: The cat first appeared in a poem – the one that appears at the beginning of the book. I wrote it during a long flight home to Sydney from the Berlin International Literature Festival, when it was dark and everyone was asleep. I really have no idea why it crept into my mind and why as a poem. I remember I was in a bad mood, and to try and alleviate my temper I started writing the first verse on a scrap of paper.

I don’t have a cat at home. In fact, the only cat I’ve lived with was the family cat when I was a child, a grey tabby called Ricky. He was a perfectly gentle and apparently unmenacing animal. But when I was about four, I did come across him one day with a bleating baby sparrow in his mouth. I was very disturbed; it was like a revelation of some sort, really. (You will note I have included this scene in the book.) I’ve not lived in a house with cats since, although they are fascinating and obviously beautiful animals. They always remind me of ghosts.

[Cats] are fascinating and obviously beautiful animals. They always remind me of ghosts.

J: You have a PhD in literature – is that how you became a children’s book writer? Could you tell me a little about your thesis, why you did it, and if it still influences your daily (writing) life?

U: Ah, no, I had already published several books when I did the PhD. I’m still not exactly sure why I did the PhD – certainly part of it was to find a place or community where people valued children’s books and wanted to talk about them.

The thesis topic was to do with children’s books that have ‘small people’ in them – like Mary Norton’s The Borrowers and the doll stories of Rumer Godden. The books and stories I focussed on were all published in the period immediately after World War Two, and many of them are clearly an attempt to explore the various horrors of that war metaphorically to young children. (There it is again!) They are tough books, sometimes brilliant. My novel The Red Shoe was a sort of accompaniment to the thesis, and it does contain a small person, Matilda’s invisible friend, Floreal.

J: What does a typical day look like for you? What’s your writing process? And what do you do when you’re not writing?

U: I’ve been through a few methods of approaching writing in my life, depending on my circumstances. When I was working full-time in an office I used to get up very early (about 5am) to write for an hour before leaving the house. I became a bit addicted to the marvellous silence of that hour actually.

Then when I was home with small children I used to write while the baby was asleep – so with a certain urgency! I found the isolation at home with the children in fact rather wonderful for my writing. Nobody bothers you when you have small children (nobody wants to see you!) and so you’re left blissfully alone with your thoughts and the company of the very young, who, mentally-speaking anyway, are largely in their own private worlds. When I look back on that time I feel as if I was close to the hub of the universe, somewhere deep and elemental, just tiny new lives and their mother.

I’m not much of a planner, so that means I’m messy, always off in this direction and that, constantly deleting, rewriting, rearranging, back-tracking.

Now my time is freer I still tend to write in the mornings, and not more than a couple of hours – I get vaguer and lazier as the day goes on. I’m not much of a planner, so that means I’m messy, always off in this direction and that, constantly deleting, rewriting, rearranging, back-tracking. Lots of walking by the river and frowning and thinking and trying to work it all out. IT’S A NIGHTMARE!!!! I would love to be more methodical but I don’t seem to be able, even when I try my hardest (sob).

When I’m not writing I lie around a lot. I read of course, I walk the dog. I used to swim more or less regularly but now I don’t like getting wet, which is a drawback for swimming, it must be admitted. I do my French homework and my Latin homework. Gee what a dreary life it sounds! (I’ll have to find something more dramatic to report.)

J: Lastly, what are some books – for kids or otherwise – that you’ve read recently and want to tell the world about?

U: I love the French novelist Patrick Modiano – at least what I have read of him. I have read Horizon and Dora Bruder and he wrote a charming book for children, Catherine Certitude, about a little girl who prefers not to wear her glasses because the world looks better when it is blurry….

Jane Arthur

Jane Arthur's debut children's book, Brown Bird(PRH) was published in May 2024 to widespread acclaim. Jane is co-founder of The Sapling, co-owned and managed GOOD BOOKS, a small independent bookshop in Pōneke Wellington and has twice judged the NZ Book Awards for Children and Young Adults, in 2019 and 2020. Her debut poetry collection, Craven (VUP) won the Jessie Mackay Prize for best first book of poetry at the 2020 Ockham NZ Book Awards, and her second collection, Calamities!(THWUP) was longlisted for the Mary and Peter Biggs Award for Poetry in the 2024 Ockham Awards.