Mitch Marks reviews Moa, a collection of comics by James Davidson (published by Earth’s End), and makes a case for the importance of graphic novels in general.

It’s well documented, and kind of a no-brainer, that combining words and pictures is a great way to help ‘reluctant readers’ – both in enticing them to pick up a book in the first place, and to make the actual reading easier in the second:

The brilliant thing about the graphic novel is the way they offer dyslexic readers several different cues to the story. If a reader gets snagged on the vocabulary or storyline of a graphic novel, illustrated pages offer contextual cues to help decipher meaning. (Kyle Redford, Yale)

But that’s a limiting framework to view children’s and YA comics and graphic novels within. It implies that the artwork is secondary or supplementary, there to explain the text; or to others it might suggest the other angle, that the text is merely there to make a picture book ‘readable’. Last year at Writers Week in Wellington Kate De Goldi spoke to Mariko Tamaki, an award-winning Canadian artist and writer who collaborates on YA graphic novels with her cousin, illustrator Jillian Tamaki, and is now writing for Marvel and DC – the superhero comic ‘big gun’ publishers. Kate told Mariko that, as a children and YA author herself, she was envious of the graphic novelist’s superior advantage when it comes to ‘show don’t tell’, the adage of creative writing teachers worldwide. With an illustrated text, you get the opportunity to literally show an event, a surprise, an expression – De Goldi’s example was not having to say ‘her jaw dropped’. There’s an extra layer of subtlety that an author or illustrator can work with, as well as an extra layer of unsubtlety, with drawn sound effects and repetition of textual themes in imagery.

In France there’s no question that comics are both art and literature. Known as bandes dessinées (drawn strips), the form is ubiquitous. It helps that the potential audience is huge – the French comics scene has close ties to the Belgian scene, and between them they have the French and Flemish markets across Europe, and beyond, covered. The major titles to come from the area are also widely known as English language children’s comics. Think Asterix, The Smurfs, Tintin, Lucky Luke: all translated into multiple languages from the Franco-Belgian originals. Apologies for quoting from Wikipedia, but this passage does sum up the important distinction between Euro comics and those of the US:

The term bandes dessinées contains no indication of subject matter, unlike the American terms ‘comics’ and ‘funnies’, which imply a humorous art form. Indeed, the distinction of comics as the ‘ninth art’ is prevalent in Francophone scholarship on the form (le neuvième art), as is the concept of comics criticism and scholarship itself. (Wikipedia)

France allows comics a place in schools and, perhaps more importantly, beyond childhood; they have the readers, the publishers, the Angoulême International Comics Festival (where New Zealand’s own Dylan Horrocks has appeared regularly). French-New Yorker Françoise Mouly, art editor of The New Yorker since 1993 and before that co-publisher of the seminal Raw comics magazine, is attempting to raise the understanding and appreciation of comics as a teaching aid in the US by publishing graded comics and curriculum-aligned teachers’ guides under her Toon Books imprint. Slowly, the idea of comics being a distinct genre from kid’s picture books – a more literary and nuanced, more likely to last beyond the teenage years, genre – is spreading.

Which brings me back to New Zealand. We had a short and unusual love affair with Terry Teo in print and onscreen in the ‘80s and again in this decade. And part of the credit for the revival of Bob Kerr and Stephen Ballantyne’s skateboarding sleuth can be given to Earth’s End, the publisher of Moa, who reprinted 1982’s Terry Teo and the Gunrunners in 2015 as a TV tie-in. In other comics-lit news, Sarah Laing’s graphic memoir Mansfield and Me (Victoria University Press) was longlisted for the 2017 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards, sitting awkwardly in the Illustrated Non-Fiction category alongside photography, wine, women and painting. Unsurprisingly, the more obviously ‘illustrated’ (read: glossy photos or reproduced works of art) and ‘non-fiction’ made the shortlist, and Laing’s work of what I would call ‘fictionalised fact’ went unrewarded. We want to like comics, we’re just not sure how to get there, and there’ll be some awkward shoulder-rubbing and brow-furrowing until we do.

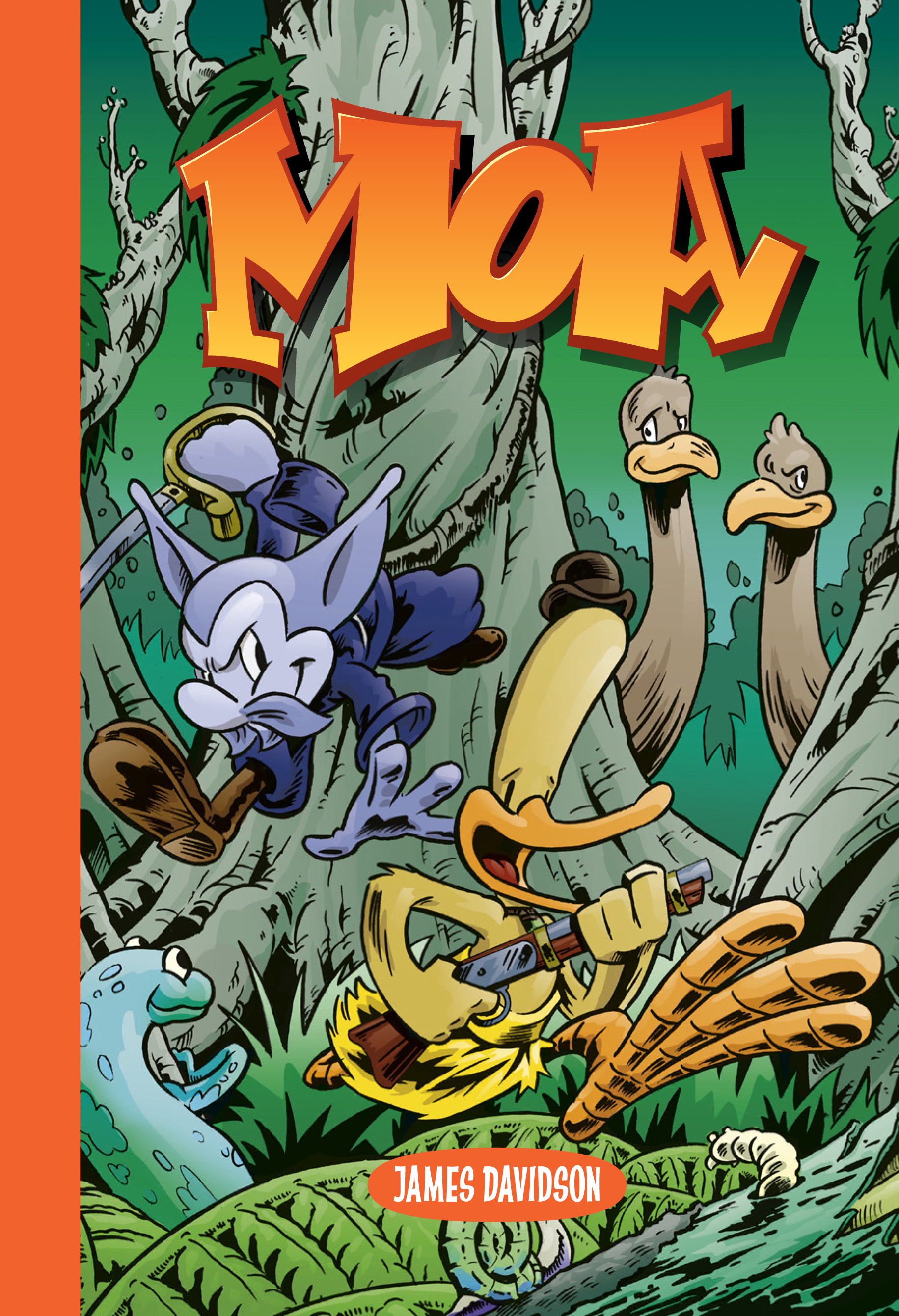

To the book at hand: Moa is a collection of the five comics in James Davidson’s previously published comic book series. Davidson is an educator himself, Head of Arts at Opunake High School, and his artwork is seriously tuned in to what kids like. The publishers are equally tuned in to what adult buyers of kids’ book like, including lush paper stock, a hardcover and dark, inky printing. A winning combo.

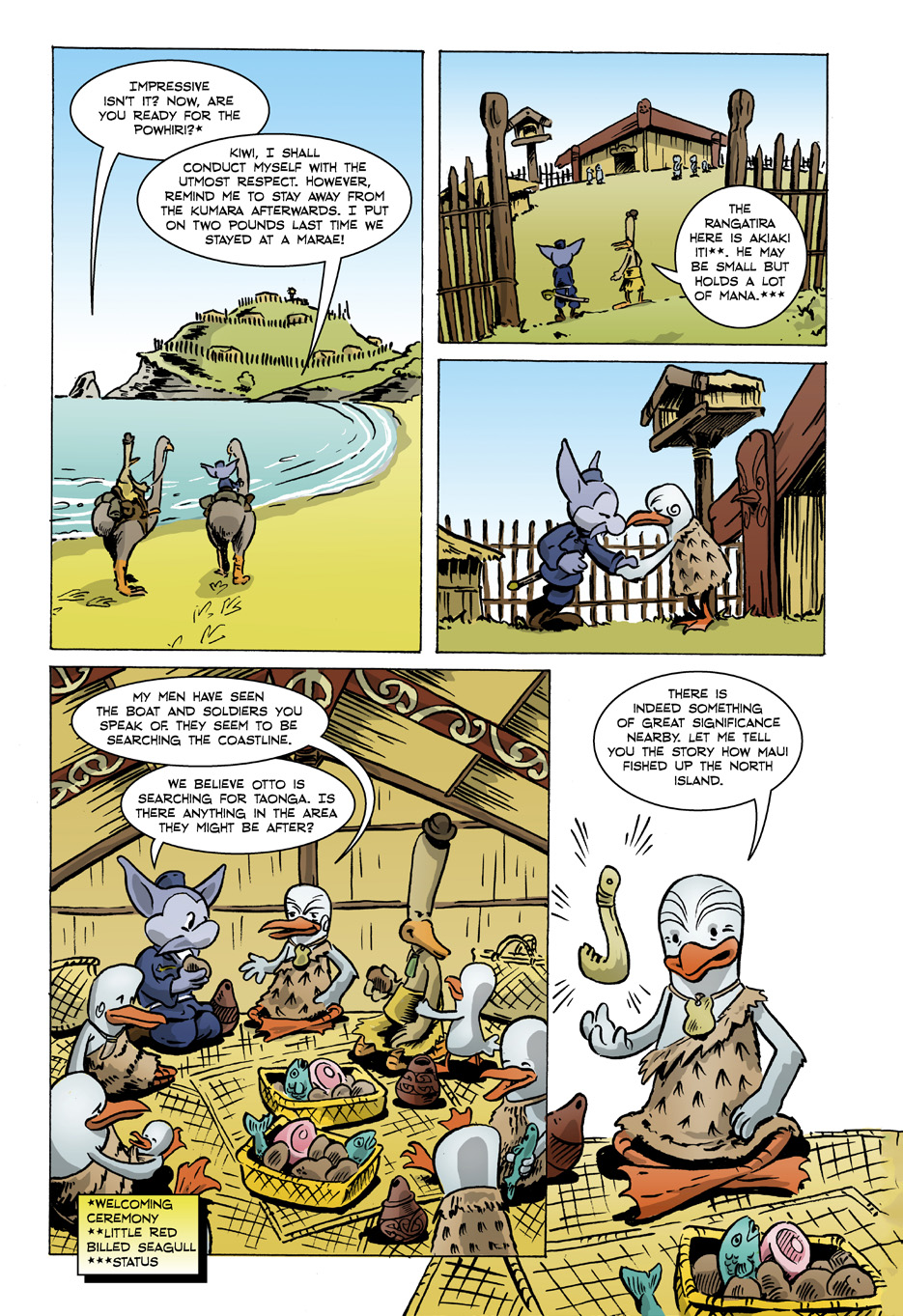

Moa Rangers Kiwi Pukupuku and Possum Von Tempsky romp around colonial New Zealand landscapes, falling into Maori myth, and throwing Kiwi slang and humour around with a joy that harks back to Terry Teo and its ‘Kaupati’ in-jokes. It feels like a story that is genuinely made for New Zealand readers – the artwork is reminiscent of American Jeff Smith’s Bone series which is the subject of a Scholastic ‘Using Graphic Novels in the Classroom’ teaching guide, and having seen for myself how popular the title is in the YA section of New Zealand libraries, the familiarity of the artwork can only be a bonus. Every page of Moa is crammed with action in both text and image, and if you’re a teacher or parent looking for learning opportunities, there’s plenty here too – language, history, choices – but they’re secondary to the story, as they should be. There’s also Kurangaituku (the bird–woman from the legend of Hatupatu) who talks like Yoda. I’m sold.

My only problem, and it’s why I have given such a long preamble to talking about the title itself, is that there is a glaring problem with taking this book into the classroom: it’s full of typos, misspellings, and jarring grammar and language. Here I have to add the disclaimer that I am an editor and proofreader by trade, so I gave serious thought about whether to mention this or not, and whether it mattered to those not pedantic or in the book trade, but in the end – after checking my assumptions with a primary school teacher aide who is the parent of two pre-teens – I think it bears mentioning. Most of the dialogue avoids contractions, opting for I am, I will, do not, over the easier and shorter I’m, I’ll, don’t that kids are well versed in by the time they’d be reading this book. Sometimes the text on dark backgrounds is hard to decipher. These combine to make reading out loud and reading to yourself equally stilted, and it’s a shame that the text wasn’t given the loving treatment that the pictures were. Misspellings throughout could be considered a small thing but if we want to raise the status of comics in this country, as well as literacy levels, then they’re a problem.

So to summarise, I loved this book. I love that it exists and I wish it had been around when I was in school. It’s fun, colourful, beautiful and distinctly of Aotearoa. Ignore my editorial misgivings and buy it, read it, share it. And in doing so, you’ll nurture not just our kids but also our comics industry, which will eventually mean there’s enough time and money to do as much for a comics publication as for a trade paperback. And the Ockhams will have a Graphic Novel category to recognise our winners.

Mitch Marks

Mitch Marks has been a comics fan from a very young age. She currently lives in Auckland and works as a freelance editor and publication designer, runs the fledgling publisher Foolscap Publishing, and used to own and run a comics and record shop in Melbourne.