Lily Max author Jane Bloomfield caught up with UK author/illustrator Lauren Child during the recent Auckland Writers Festival. We captured some of their fascinating whirlwind conversation here, learning about inspiration, thrillers, sunglasses and Seventies childhoods.

I expected to feel incredibly nervous interviewing Lauren Child, famous British children’s author/illustrator, TV producer and self-confessed starer out of the window. She’s sold over three-million books and been translated into 30 languages. But from the minute I met her and her team, I felt like I was part of a cool girls’ weekend. With cool books.

We caught up in the Sky City Grand Foyer during the Auckland Writer’s Festival. She’s a strikingly glamorous woman. Tall. Sartorial. Chic. Elegant but edgy. Ears adorned in a delicate array of jewels that would make Faberge jealous. Tailored jacket with a teapot-patterned shirt. Killer black boots. Pinky-highlighted hair pinned up with a diamanté barrette. Sapphire blue eyes sparkled above a friendly smile …

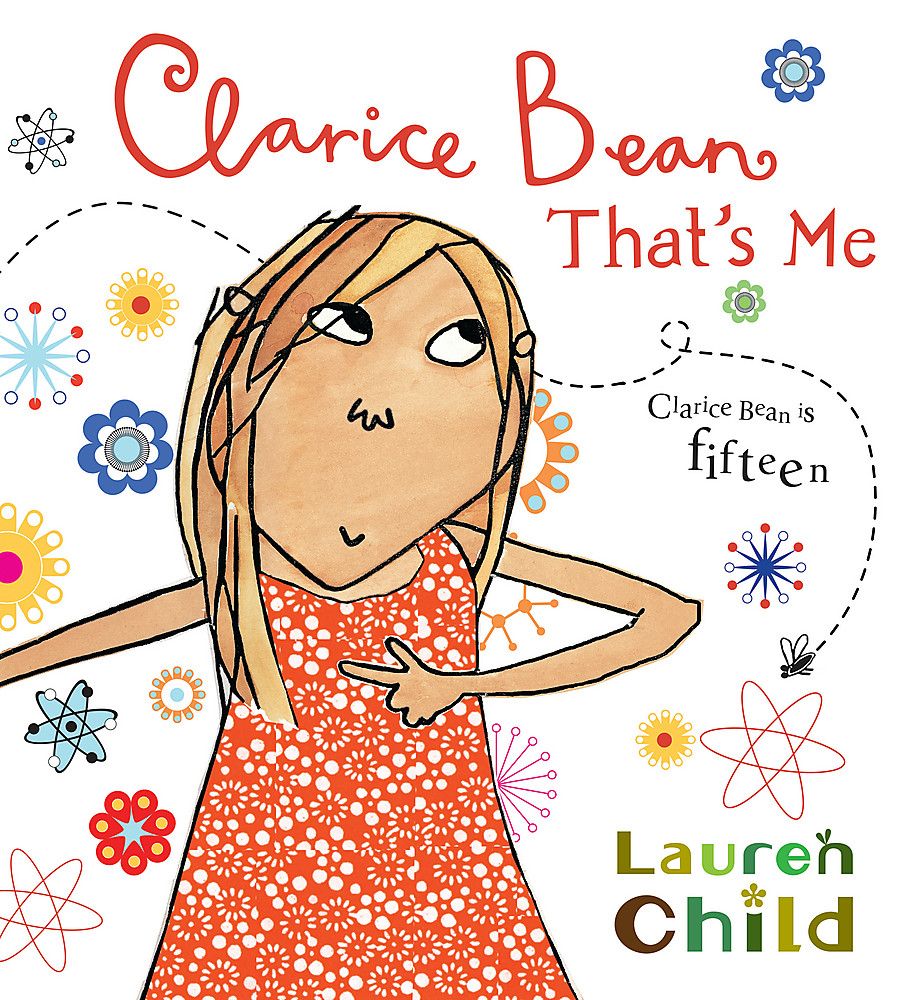

Jane Bloomfield: I’m a huge fan. I read all your picture books over and over to my daughters and son (who are now teenagers). I still have visions of That Pesky Rat in the dumpster with his used-teabag pillow! My Uncle is a Hunkle – I love. Your writing and illustrations were just so refreshing and funny. Your use of curvy typefaces, funky endpapers, and quirky bios – so fun. Your Clarice Bean novels made me want to be a children’s writer.

Lauren Child: That’s so nice. Sometimes it’s just the catalyst you need, seeing someone’s work you totally admire. I remember visiting America and children’s author/illustrator Maira Kalman’s books had the same effect on me.

J: You’ve written and/or illustrated 45 books in 18 years. That’s a phenomenal workload. Do you ever rest? Or sleep?

L: I was one of those people who really didn’t know what I wanted to do. Then once I’d figured it out and wrote a book, no one wanted it. It’s a bit like when you get really geared up for something – ‘okay, I think I can really do this, I think I can do this’ – then it’s all pulled away from you again. And again. Then when I was published, I just felt like I really had to get on with it. I don’t sleep much.

J: What do you think made publishers suddenly believe in the Lauren Child product?

L: That’s a very interesting question and it’s hard to know what the answer is. I think it might simply be them seeing it at the right moment. Because with Clarice Bean there were four or five years of them saying, ‘we’d never publish anything like this’. The British said, ‘it’s too American’. The Americans said, ‘it’s too English’. And I think that happens sometimes. And then someone relooks at it all those years later and then decides, oh this is interesting. So you never know.

J: You first wrote Clarice Bean as a movie. But a friend told you it was a book. Is this because your writing process is visual?

L: I was writing picture book ideas and submitting them with sketches. The publishers would like something about them. But they weren’t very good at pointing out what it was that they loved and then steering me in the right direction to bring the most out of it.

Every now and again you meet a publisher who is good at doing that. And editors and designers who are good at doing that. But others, rather than them saying, ‘we love this part of your work, but maybe you could think of structuring a story like this’, they would just hand me someone else’s book and say, this is a very successful book. You should write one like this. And I’d say, yes, it is. But it’s already been written so there’s no point me looking at it.

I think I just gave up. Then someone very cleverly asked me: what is it that you really love? What are you really passionate about? And I realised it was film.

I’d gone to see Edward Scissorhands and I’d really, really loved it. I’d heard of Tim Burton before but he was not well known. It was early on in his career. But what I saw in his work was his whole vision. Everybody he’d got involved in his film was very beautifully chosen. The movie felt entirely original and it felt like his creative vision. I felt really inspired by that and I ended up writing Clarice Bean, That’s Me, my first picture book. Although it had nothing in common with Edward Scissorhands there was something I understood about creating a world and a personality, so it had your voice. So yes, I did write it as a film!

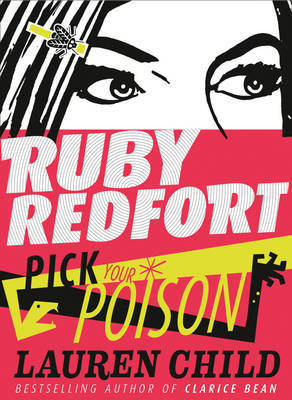

J: Ruby Redfort first appeared in Clarice Bean, Utterly Me. The six books’ detective plots are very complex after the whimsical, family-based Clarice Bean stories. How was that writing transition for you?

L: Ooh, that was a head spin because, yes, Clarice Bean is generally about someone small’s observations of daily life. With Ruby you have to bring not only the thread of one plot but the thread of six together.

I can’t do plot plans. I don’t think it’s something I can learn to do. I have had editors get very frustrated because they want you to plot it out. They know that it will be easier if you do and you’re writing to an end point. But I just get really bored if I plot. I can’t do it.

Then I read Stephen King’s book On Writing and he talks about that exact same thing and he doesn’t plot his books either. That made me feel very secure somehow. That was really reassuring. Because I think of him as a master plotter. Stephen King said, Look, if I plot my books I know what’s going to happen, so that means there’s a good chance someone else will know what’s going to happen!

J: Did you look to the early masters of murder, mystery and suspense for inspiration?

L: Hitchcock was a huge influence. And I listened to a lot of Raymond Chandler detective books on audio. He has wonderful dialogue.

In Hitchcock films like North by Northwest there is such wonderful comedy. I love the plotting. It’s a proper thriller. Then you get these lovely interludes when he’s on the train with a beautiful woman and you don’t know if she’s a goodie or a baddie, and they take that pause in action to sip a cocktail. I think that’s why they work so perfectly as thrillers, because you relax and you have that moment of oh, this is all really safe, and then the drama builds again you get full of dread.

I always feel, particularly with modern films we just go from one piece of action to another. We don’t allow the audience to breathe a sigh of relief. That’s what Jaws does so brilliantly. You relax when the characters are at home, because they’re indoors and you know there’s no shark. You feel that sense of relief. And then you go – please don’t go out on the boat! Please don’t go out on the boat! And then they do. It’s that great sense of jeopardy.

J: All your characters have the best names! Karl Wrenbury and Betty Moody in Clarice Bean. Clancy Crew and Del Lasco in Ruby Redfort. Do you have tips for children’s writers for naming characters?

L: I really think a lot about it. I can’t write a character until I’ve got their name. Occasionally I’ve changed a name. If I go back and look now at Clarice Bean, Don’t Look Now. I go, oh no, there are too many ‘Ks’ in this book. There’s a Kiera, and a Kurt and a Karl. I should’ve made the Karl with a ‘C’ because I think you hear it differently. But Karl Wrenbury just seemed so right. I think about it a lot.

As for tips for writers – those dictionaries of names are quite useful when you get really stumped. They’re quite handy. I think you can get drawn all the time to the same kind of names.

J: Is there an underlying theme to your body of work?

L: All my books are very character-driven. I’m very interested in family relationships. I love writing dialogue. They all have that in common. It’s so much easier when you look at other peoples work and you can see those things very clearly. But, yes, there are obviously themes I get really interested in. I see it a lot in my illustrations: Lauren, you’re drawing a tree again! There are a lot of trees in my books.

J: You work from home. Is your studio big small? Cluttered or tidy? Are you a collector?

L: I am a collector. I like stuff. I was a minimalist for a long time because I was of no fixed abode. I was often housesitting for people. And although it is all neat and tidy and you just have a bag, I felt really strange because I’m just a type of person who likes things. So I’ve decided to embrace that, instead of keep trying to be a minimalist. I know that makes life simpler. But I’m not! So forget about it.

What I do find difficult is that I’ve never really had a good place to work. I’ve either been working from a small desk in an office, or a small room in my house. I have finally bought a studio to work in. I’m just moving in now. I can’t wait. There is something psychological, not only for me, but for other people. People always think you’re at home so they can always phone you about work.

J: How do keep in touch with your fans? Do you use social media?

L: Letters! I hate social media, generally, except for now I’m doing Instagram. Because I get it. You can take a picture of a marble and you don’t have to say anything. It feels less aggressive and less needy. The only thing I don’t like about it is that people can like your stuff and I don’t really want that. Because it makes you worry then if people don’t like it and I’m just putting it up because it interests me. I don’t like the neediness of social media. I can see where it’s good, but I don’t really like it.

J: You said in your bio in Clarice Bean, Utterly Me your ambition when you were younger was to wear sunglasses on top of your head, which you’ve achieved. Do you have many pairs of sunglasses?

L: I don’t have loads of them. But it’s such a funny thing. When I was small it was really all I could think of: when you’re a woman you get to wear sunglasses on the top of your head. I think I saw it first on Charlie’s Angels. Then my friend’s mum, who did the Thursday school run, would always have her sunglaszses on the top of her head. She looked marvellous.

J: All your books are full of humour and are very funny. Often deadpan. Were you a joker or serious child?

L: I was always making jokes. I don’t know if it’s middle-child syndrome. My older sister was very responsible. She’s very Charlie-esque. She was very good at looking after us. And my little sister was that sunny child, always the cute one. I became the joker.

J: Growing up, your dad was head of art at Marlborough College and your mum was a primary school teacher. Was there a lot of extra tuition in art and reading at home?

L: I suppose so, but it was done in a not-realising-it-was happening way. That was the advantage. Mum was very good at taking us to the library. We went to the library maybe twice a week. She was a passionate reader. So it taught me to love the library. It felt very normal to be there. We always, always read a story at night. I just thought that was normal.

And she taught me as well for a year. She was a very good teacher. She taught us creative writing. She had a very good understanding of it, because she read so much. She’d try and get me to start my stories with something punchy, because I always started with ‘Once upon a time’ and ended with ‘happily ever after’. Those stories were really boring. I’ve still got them.

J: Once you were drawing a wolf and your Mum said, ‘Oh darling, that’s a lovely mouse!’ How are your horses these days?

L: When they asked me to illustrate Pippi Longstocking, I knew that book off by heart so it almost felt like my book. As a child I’d loved it. I knew what I wanted to illustrate. The only thing is if I’d written it, I wouldn’t have written a horse into it because I can’t draw horses. If you look at the book you see I do bits of the horse. You see the head and the legs but they’re all separate you don’t see them together.

J: We both grew up in the 70s. In New Zealand, we were given a lot of freedom. Often the only instruction would be – go outside and play, children. Was that the same for you in the UK?

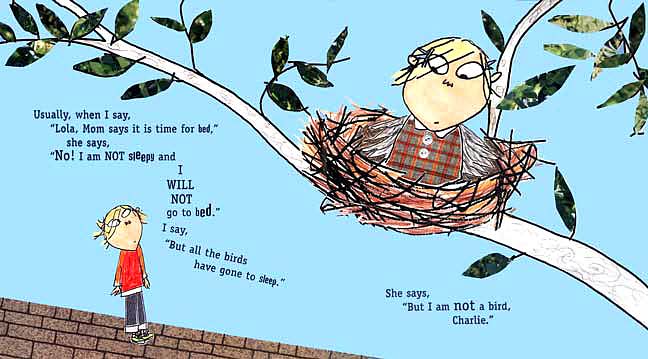

L: Yes, my mum was very much like that. Children often ask me why there were no parents in Charlie and Lola. And I say, I really want it to be about a child’s conversation and a child’s imagination. And a child’s imagination is not something that you can step into as an adult. It’s that Peter Pan thing, once you’ve grown up you can’t go back.

My parents weren’t playing with us all the time. And they weren’t taking us out all the time. I don’t know what it’s like here now, but back home it’s definitely – unless you’re not doing things with your children all the time, you’re a bad parent. My Mum would say, ‘Oh, just go and run about in the garden. Get out. Get out of my hair!’

J: And be home for dinner!

L: Exactly.

—

Lauren is currently working on an illustrated chapter book series for young readers.

Jane Bloomfield

Jane Bloomfield is the author of children's novel, Lily Max: Satin Scissors Frock, which was a finalist at the 2016 NZ Post Children's Book Awards. The sequel, Lily Max: Slope Style Fashionwas published in 2016, and the third book in the series, Lily Max: Sun, Surf, Action,was published in 2017. Jane was born in Takapuna in 1964.