Writing children’s books may seem romantic at remove, but — as with many things — it’s less glossy up close. As Kiwi writers Juliet Jacka and Sally Sutton can attest to, for every passionate line they write, only a lucky few sentences ever see the published light of day.

So what keeps them going, despite the drawers bulging with rejected manuscripts, and the desks (or favourite cafe table) strewn with paper and empty coffee cups as they slog their way through their next recalcitrant plot?

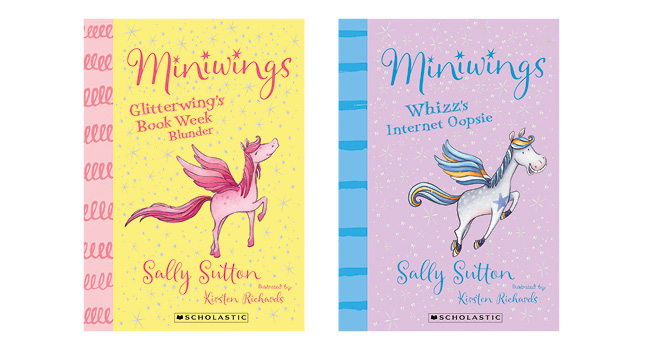

It’s their love of writing, of course, as Juliet and Sally discovered in their following email chat about their new junior fiction chapter book series, Miniwings (Sally’s) and Frankie Potts (Juliet’s).

Juliet Jacka: What gave you the idea for the Miniwings series?

Sally Sutton: I wanted to do a series about horses, because I know how popular they are with kids. The trouble was: I know nothing about horses. Nothing. And there are already a lot of horse books written by people who actually do know lots. You can’t fake something like that. The solution was obvious: my horses would be completely made up! Then I could do anything I liked with them, and I wouldn’t even have to know the difference between bridle and a halter.

When my two girls were younger, their favourite toys were their collection of Schleich horses — those little plastic German ones. They are very expensive (not to mention extremely anatomically correct!). They took those horses everywhere, even overseas on holiday. I remember the security guy at the airport bursting out laughing as he scanned their bags, saying: ‘There sure are a lot of hooves in there!’ I thought: what if those little horses came to life when the grown-ups weren’t looking? What if they could fly, and speak their own language, had their own personalities and were super-naughty? What if the girls had to keep them a secret? And so the Miniwings were born …

S: How about you and the Frankie Potts series?

J: My idea for Frankie came into being thanks to an exercise I did for a workshop course in writing for children at Victoria University. We had to string together a bunch of unrelated words into some sort of story, and when I tried that, out popped Frankie Potts. Although, initially … she was a he — Arty Potts — until a publisher (somewhat interested in my manuscript) asked me to turn him into a her, as they thought it would be a better fit.

What was the journey to publication like for Miniwings?

S: I have to admit it was pretty arduous. I envisaged the books as a series from the get-go, so wrote the first drafts for all six books at once, to maintain consistency. My original target age group was younger: five years and up, instead of the current seven-plus. It was hard going. The series was rejected more than once until the clever people at Scholastic said they liked the idea — just not the execution (though, of course, they said it much more delicately than that!).

I chose one story and completely re-imagined it, changing the characters and tone, loosening the language, upping the word count, changing the text from third person to first person, turning it into a diary format and injecting a whole lot of humour. Scholastic liked it, and took the series. I then rewrote the other five stories one-by-one. I’m really grateful for this editorial input. The stories are much, much better now.

I envisaged the books as a series from the get-go, so wrote the first drafts for all six books at once, to maintain consistency … The series was rejected more than once …

J: I had no idea at the time that my story would turn into a series, as I wrote the first book — Frankie Potts and the Sparkplug Mysteries — as a standalone piece. But luckily Frankie’s the kind of character who finds mysteries wherever she goes, so new ideas and stories are easy to dream up for her, and the series fairly much fell into being.

I reckon my biggest challenge with writing a series is continuity. It’s surprisingly hard to keep track of all the characters I’ve invented along the way, particularly now I’m on book four, and there are (I think …) 11 dogs, an overweight donkey, and a pig, parrot and iguana, as well as all the humans characters in the mix too. Luckily that’s where the great editors at Penguin Random come in, and they help me shepherd everyone along in a somewhat orderly fashion.

On Friday, I found myself wondering during my writing session at a cafe when and how you fit writing in? I, like you, have two girls. I work 30 hours a week. So, for me, Friday is my writing day. I start off with an early morning yoga session then go to a cafe afterwards, and typically edit the chapter I wrote the previous Friday, then write a new one. I love the background cafe buzz as a writing backdrop.

What does a typical writing session look like for you?

S: I don’t know how you do it, juggling work, writing and motherhood! I am incredibly lucky to be a full-time writer. My girls are a little older now — ten and 13 — so I write while they are at school. It’s just as well I have extra time, because I’m a really slow writer. It takes me a long time to get down the first draft. I have tried to speed myself up, but it never works; it just takes longer at the other end, when I have to rewrite everything because it’s no good. I will usually do lots of drafts too, spending ages editing and refining.

I like to think I could write anywhere, but really, I prefer home. My favourite writing props are (too much) coffee and silence. I usually try to do new writing in the morning, when I’m fresher, and editing/emailing/other tasks in the afternoon. But in reality, this changes day to day.

J: I love the horse language you’ve invented for the Miniwings. What’s your favourite saying you’ve invented and how hard is it coming up with their lingo?

S: Making up the Miniwing-ese for the horses was one of the most enjoyable parts of writing the series. My favourite sentence so far is probably when Moonlight bites Comet in the sixth book, Moonlight and the High Tea Hiccup: ‘Owpie! Keep your fanglers off my fly-flicker, you peskery old trotter!’ (Translation: ‘Ouch! Keep your teeth off my tail, you naughty old horse!’)

I really love playing around with words, and trying out how they sound. I studied European languages at university, selecting the languages on the basis of how beautiful they were to listen to. It is actually quite hard, though. It’s tricky to keep all those words and definitions consistent, and also to use the words in the same way grammatically each time. Even though there’s a dictionary at the back of each book, I want kids to be able to guess what most words mean without having to look them up. Kids also need to be able to read them easily — so the language must be funny, but not too complex.

Writing Miniwings, I imagined it taking place in New Zealand or Australia, but was not specific about the setting.

How do you feel about setting a book in a particular country. Am I correct in thinking that the language and seasons in Frankie Potts are geared towards an American audience?

J: I actually had England in mind when I wrote Frankie Potts, not because I was being particularly strategic about possible markets for the book to sell in, but more because Frankie just emerged in that context, possibly influenced by the fact that I grew up reading classic English children’s books, plus my husband is from England and I’ve spent a bit of time over there. So that seems to suggest that, no, awareness of the international marketplace doesn’t affect the type of story I write. Although perhaps it should, a little more, but so far I tend to get stuck in and follow where the story leads me.

S: Oh, England! I should have known that. I totally agree with you that the story dictates its own mood and you have to be true to that. I would never try to inflict a particular setting on a story if I felt it didn’t suit. Having said that, I quite deliberately chose not to mention any real places in Miniwings in case the series went international. These stories could really be set anywhere, and I quite like the idea that kids can ‘fill in the blanks’ and imagine the adventures taking place in their own neck-of-the-woods. I hope that’s not a cop-out.

It’s a bit different with picture books: I am acutely aware of the American market here, not so much with setting but with the language itself, because Americans have different vocab, expressions and pronunciation. An example: in my book Farmer John’s Tractor, I mention a ‘slip’ on the road (it rhymes with ‘dip’) — apparently, in the U.S. slips are called land slides. That was a disaster for my rhyme. The American edition has a completely different verse. You can’t rhyme ‘again’ with ‘train’. ‘Saw’ does not rhyme with ‘roar.’ Little things like that.

J: How strategic are you about the marketplace and publisher appetite for certain types of stories, and does it influence what you end up deciding to write?

S: Publisher appetite does influence me to a certain extent, because, like all writers, I want my work to sell. If publishers don’t think it will sell, they won’t publish it. My bottom drawer is already full of rejected manuscripts. I don’t need more. But I also think it’s a mistake to pursue a trend simply because a type of book is selling well. By the time you’ve written it, the ‘market’ will have changed; everyone will be on to the next thing. What’s the ‘market’, anyway? The market is what kids are reading. Why are they reading it? Because they love it. Write a book that kids love, and chances are, you have found yourself a ‘market.’

I also think it’s a mistake to pursue a trend simply because a type of book is selling well. By the time you’ve written it, the ‘market’ will have changed …

S: You’ve been prolific with junior fiction books; would you consider writing a picture book? Or young adult fiction?

J: I just finished the last chapter of a new junior fiction book yesterday, which I’ve got in mind as being book one of a new series. I need to polish it up then send it off to the publisher to see if they like it. Or not, as the case may be! I’d love to move into young adult fiction at some stage. I’m a massive fan of it. I have a completed manuscript called The Fringes lurking in my writing archives, but so far haven’t found a publication home for it yet.

I don’t think picture books are my forte. I find them seriously hard to write (every word has to count, you’ve got so few to play with).

I’d love to hear how you find writing picture books versus books for older kids?

S: That’s an interesting question about picture books versus junior fiction. I always like to have at least one of each on the go at once. Most of my picture books rhyme, and rhyme can really do your head in! It just goes round and round and round in your brain. I need to be able to put a picture book draft aside and come back to it. I wrote the final drafts of the Miniwings after a long period of writing picture books, and writing prose felt liberating, almost indulgent. Not that I find it easier — I don’t. It’s just as difficult, but in different ways. I’m the sort of writer who loves variety. And yes, I am indeed working on a YA novel. It’s a long way off yet, but I’m loving it. It’s different all over again…

J: What keeps you going when writing gets hard? E.g., you get rejections, you get stuck, you can’t think of the next book to write, you suddenly decide the book you’re writing sucks (etc).

S: The only thing to do, really, is to work harder. If I’m stuck, it usually means I haven’t thought something through properly. I might need to go for a walk to work it out. I might need to change to another type of writing for a bit. I might just need to battle through. When I’m totally stuck, I tell myself: ‘Right, there’s nothing for it. You’ll have to do the vacuuming and clean the shower.’ Then I will have an idea. Works every time.

When I’m totally stuck, I tell myself: ‘Right, there’s nothing for it. You’ll have to do the vacuuming and clean the shower.’ Then I will have an idea. Works every time.

J: I email my Aunt, Fleur Beale (an amazing writer, I’m lucky it runs in the family) and have a moan about whatever it is that’s bothering me. Sometimes we meet up for for a ‘writing breakfast’ so I can moan in person! She’ll offer me some philosophical and spot-on advice, and then — as you say — it’s time to get back into it and battle through whatever’s getting in the way. For me, it’s often that I’ve dived into a story without thinking things through in detail, then I’ll collide up against that and have to dig my plotline toes in.

How do you feel about the rejected manuscripts lurking in your drawer? (I have them, too. Poor stories!)

S: I was lying when I said my bottom drawer was full of all my rejections. There are way too many to fit in just one drawer!

In all seriousness, though, I really do think that everything I write makes me a better writer, especially the work that doesn’t quite make it, because I can learn from it. That sounds very mature, doesn’t it? But when a book goes really well, it feels a bit like magic — I don’t always know why. It’s great, but kind of unhelpful. The hardest rejections are the times when I suspect that the piece might actually be good. Has it been rejected because it really does suck, or just because it hasn’t found the right home yet? I don’t always know. You get so close to the work, it’s hard to judge it objectively. For this reason, I’m a big fan of putting scripts aside for a few weeks (or years), then reworking them. I’m getting better at doing that.

J: What’s your top tip for aspiring writers?

S: Write it! (I couldn’t tell you how many people have come up to me and said: ‘I’ve got this great idea for a book …’) Just write it! Then write it better. Never give up.

J: Snap! Same! Get writing. And love doing it, because it’s a funny old business, with no guarantee of publication at the end of the writing rainbow. So make sure writing for its own sake is something that gives you joy.

Juliet Jacka

Juliet Jacka started writing junior fiction stories when she was on maternity leave with her first daughter (who was luckily a good sleeper). Her first book, Night of the Perigee Moon, won the 2013 Tom Fitzgibbon Storylines Award and was published in 2014 by Scholastic. Her chapter-book series about Frankie Potts, red-haired girl detective, was launched by Puffin in July 2016 (#1: Frankie Potts and the Sparkplug Mysteriesand #2: Frankie Potts and the Bikini Burglar). Juliet is pleased to be carrying on a family tradition by becoming a published author: she's the third generation to do so. Juliet lives in Wellington, and juggles writing with family life and her work, which involves doing inscrutable digital stuff with websites.