Music journalist Nick Bollinger shares a moving account of the place books had in his three daughters’ childhoods and his own parenthood.

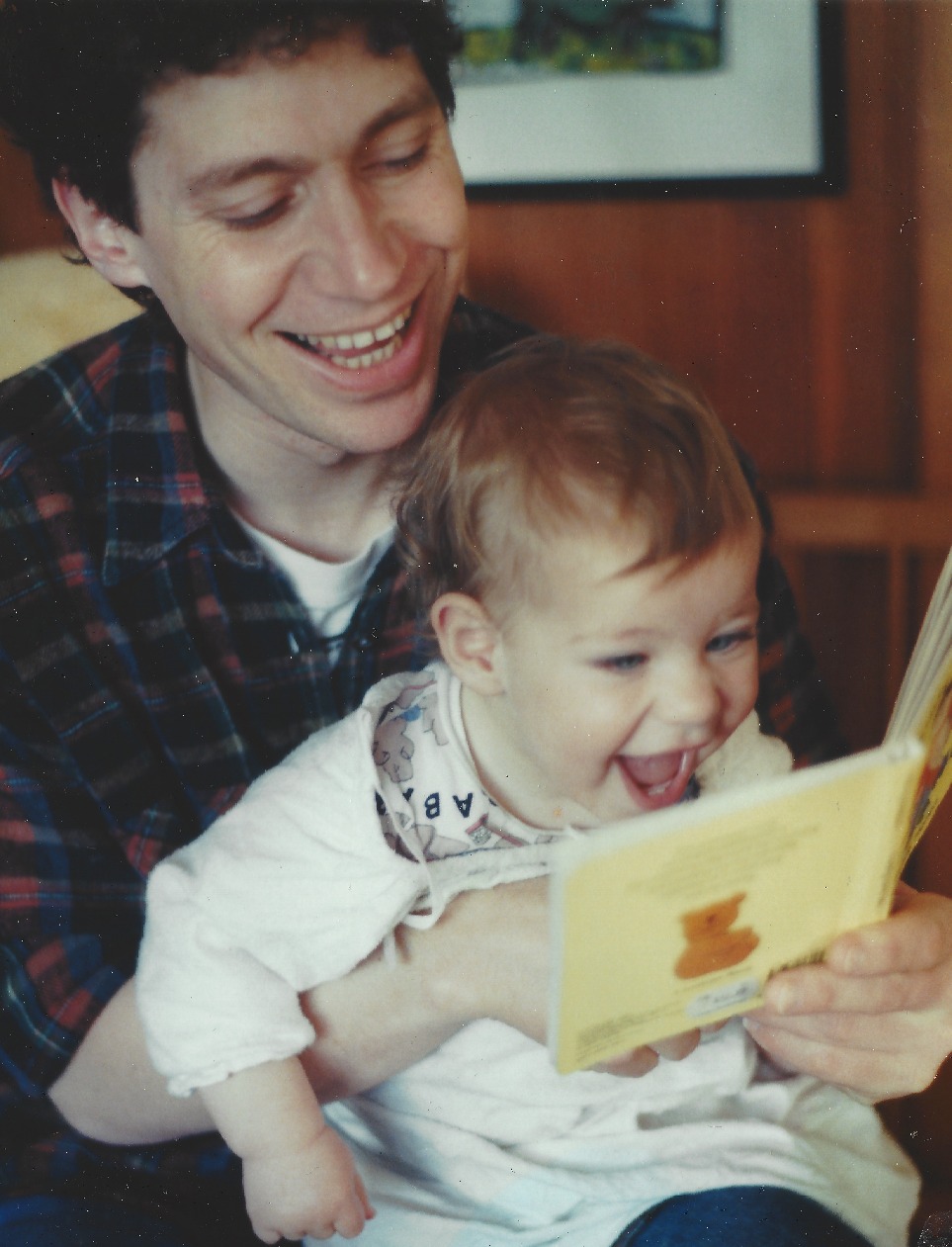

When I was a child, my favourite thing was being read to. I can still remember the smell of the tobacco my father smoked in his pipe and the soft warmth of his green shirt as I snuggled up to him with a book.

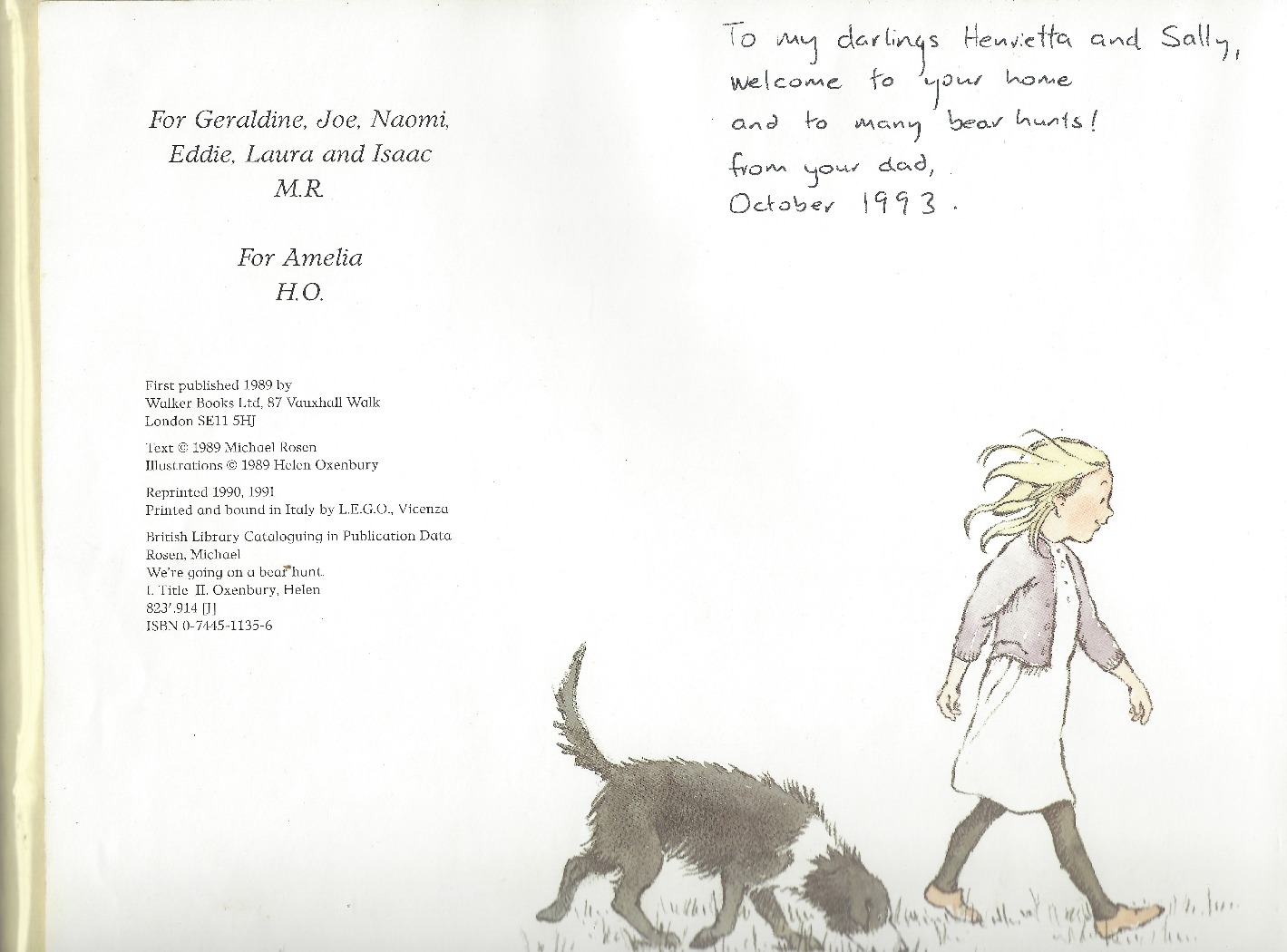

While Kathy was recovering from a caeserean and Henrietta and Sally were lying in incubators somewhere else in the hospital, I went to a book sale and found a big hardback copy of We’re Going On A Bear Hunt by Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury. On the endpaper I wrote: ‘To Etta and Sally. Welcome to your home and to many bear hunts. From your Dad.’

It would be two months before they got home. Our twins weren’t much bigger than a couple of pounds of butter and probably weren’t thinking much about stories yet.

The bear hunts began during Etta and Sally’s first year. We sailed with Max to where the wild things are, and searched for Ida after the goblins had stolen her. We followed Frog and Toad as they hunted for Toad’s lost list, played with the serpent in the rabbit garden, and worried about the contents of Mr Fox’s bag.

Some of these beautiful picture books – by Maurice Sendak, Arnold Lobel, Leo Lionni, Gavin Bishop – I had been introduced to by my sister’s kids, who I’d often babysat. Others were from my own childhood – Robert McCloskey’s Blueberries For Sal and Make Way For Ducklings, Virginia Lee Burton’s Little House, Wanda Gagg’s Millions Of Cats, and Hergé’s Tintin books.

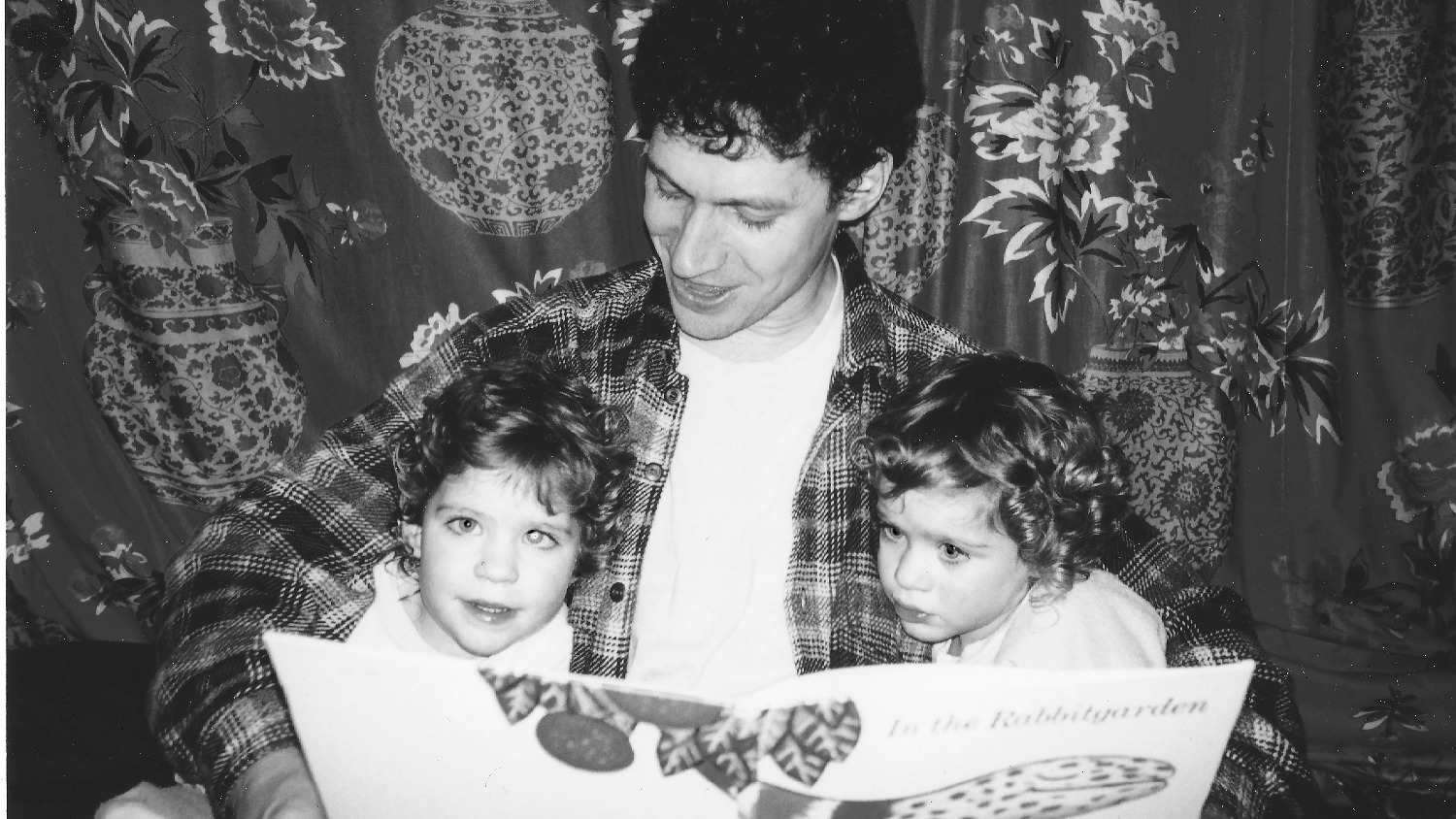

Like favourite songs on a jukebox, we returned to them again and again, until we all knew the words by heart. We read on rainy afternoons or weekend mornings, and always at bedtime. We’d sit on someone’s bed, all cuddled up together, the kids with their fingers and faces close to the pictures.

We fell in love with the characters and began to see the world the way they did. Their words and phrases became part of our daily conversation. ‘We must stop eating. We need willpower!’ Etta said, quoting Arnold Lobel’s Toad, when we’d had too many biscuits. If anyone did something clever they were a prize pazoozle, like Solomon the Rusty Nail in William Steig’s story. When one of us tripped over or banged our head, we’d yell ‘Blistering barnacles!’ like Captain Haddock.

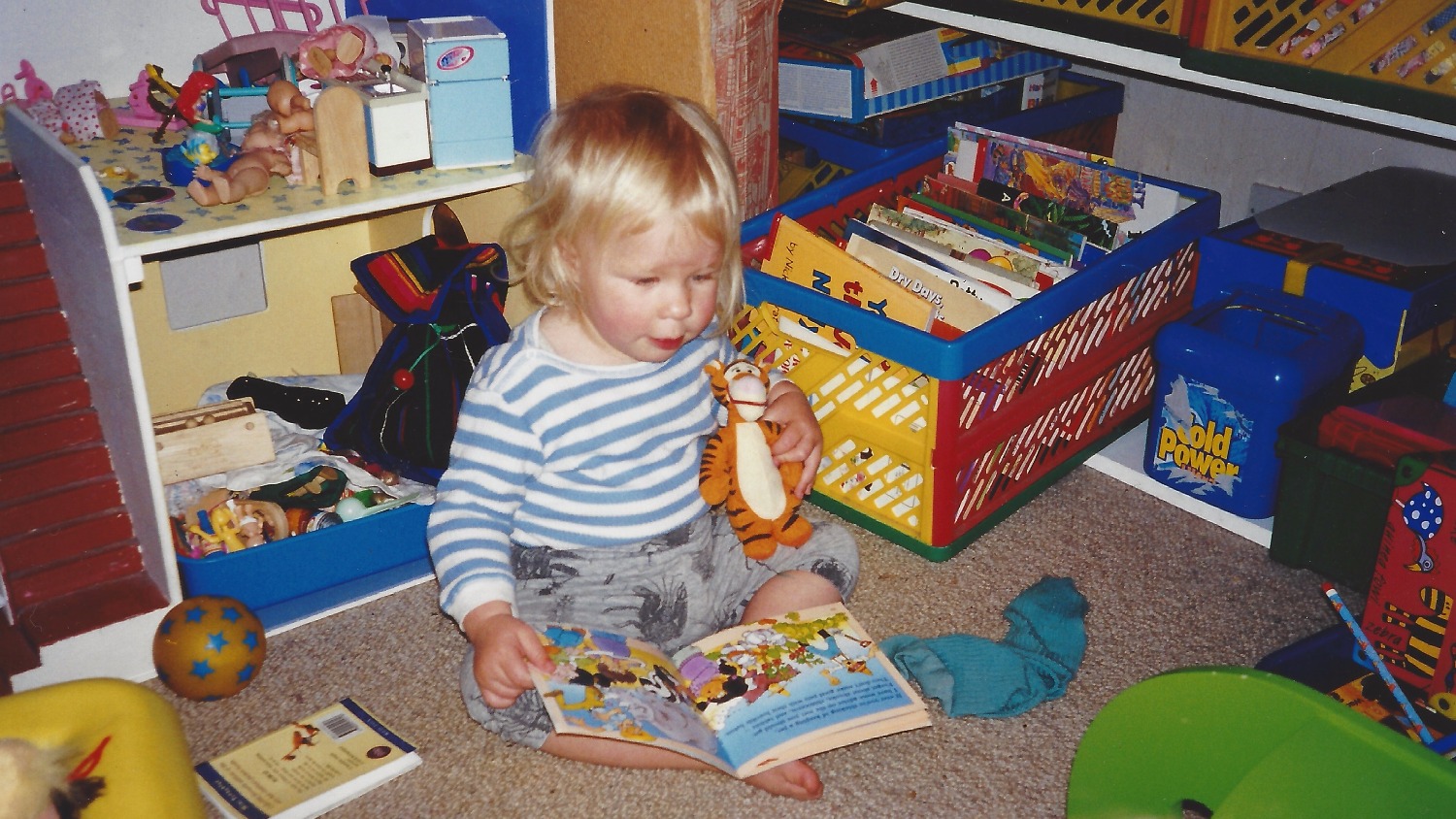

I introduced them to chapter books I had loved when I was their age, like Winnie The Pooh and The Wind In The Willows. The Magic Pudding was an instant hit. It had songs, which we made up tunes to and all sang along. We had a chapter each night. When we reached the end they made me to go straight back to the beginning and start again. We read Jack Lasenby’s Uncle Trev stories, Margaret Mahy’s The Changeover, the Narnia books and The Hobbit.

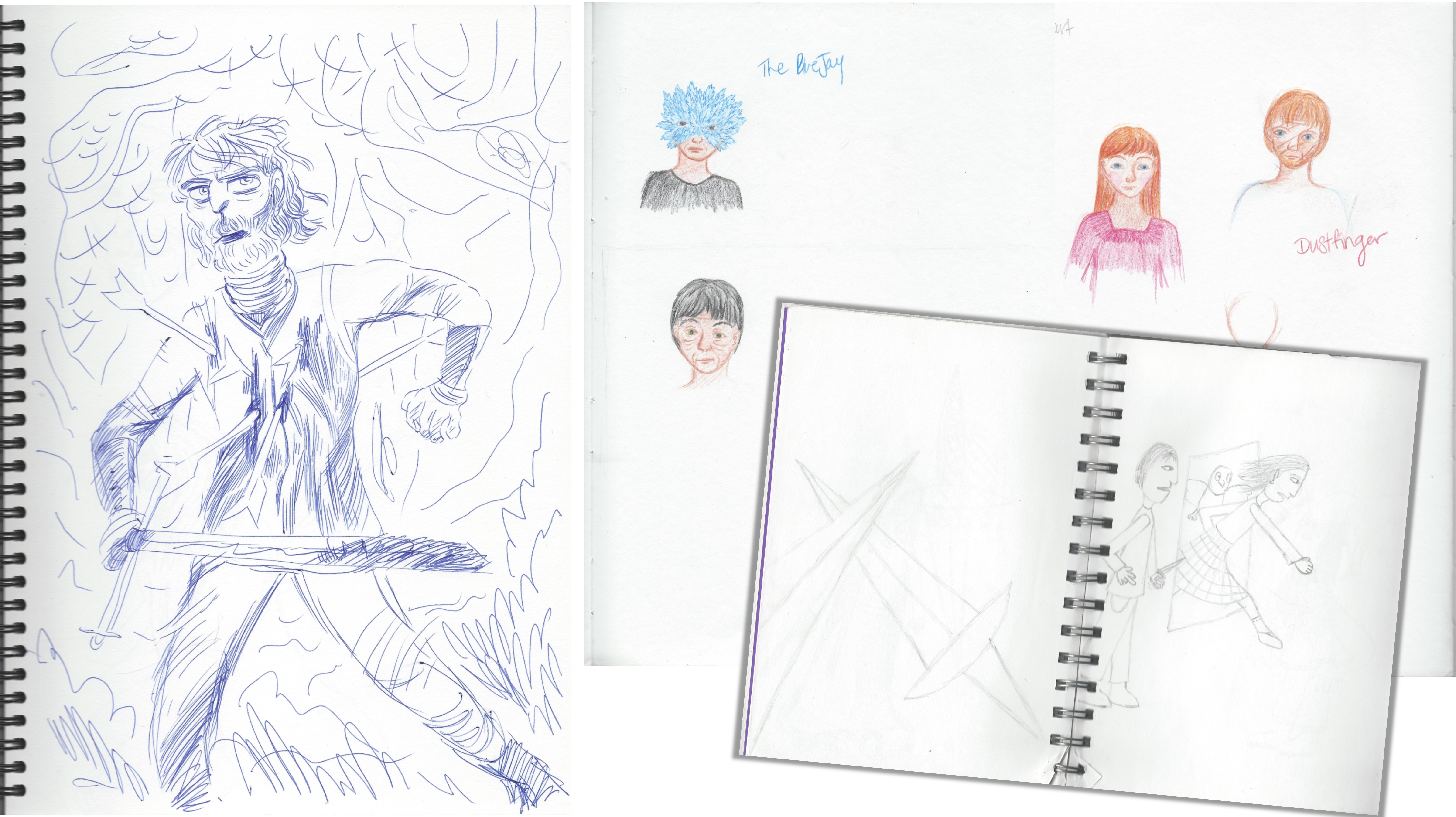

Sally was always fixed on the illustrations. She would point and trace and look like she wanted to climb into the pages. Once we started reading books without pictures, she began to draw her own, sketching as I read.

Etta was more focused on the language, asking what discombobulated meant, spicing up her vocabulary with words she had learned from the stories. She started writing her own chapter book.

We heard that The Lord of the Rings was being made into films, so we read the trilogy. It took a year. We finished the final chapter just before the first film came out.

We had entered the age of epics. The first couple of Harry Potter books had been published, and we caught up quickly. Like others of their generation, Etta and Sally were eager fans, anticipating each new volume the same way I had looked forward to the next Beatles album. While we were waiting for J.K. Rowling to finish writing The Order Of The Phoenix we embarked on Philip Pullman’s Dark Materials trilogy. One evening Kathy came into the room and found the three of us on the bed, all in tears.

‘What’s the matter? Has there been an argument?’

‘Lee Scorseby died!’ Sally and Etta sobbed in unison.

Sensing this was a tragedy but having no idea who Lee Scorsesby was, Kathy went away and began reading the books herself. We consumed everything else Philip Pullman had written. Sally Lockhart was their heroine.

Soon Elsie began to join us. She was three and a half years younger than her sisters. Some of the stories were too scary for her, but she exercised a kind of self-censorship. When Harry Potter encountered Fluffy the three-headed dog she got off the bed and silently left the room, grabbing on her way Round Robin, a safe and familiar picture book, which she got Kathy to read her somewhere beyond the reach of three-headed dogs.

I tried out my own type of censorship. I told them I didn’t like a book someone had given them about a fat pig, because it made character judgements based on physical appearances. They wanted me to read it anyway. For her sixth or seventh birthday, someone gave Sally the first book in Emily Rodda’s Deltora series, which follows the characters Lief and Jasmine on a laborious quest, through 15 interminable books. The story is interspersed with puzzles the heroes have to solve in order to survive. The plot was pedestrian and the language leaden. There were no prize pazoozles or blistering barnacles. Yet when we came to the first puzzle I could see from the size of Sally’s eyes and the intense concentration on her face that she was entranced. Whatever the books lacked in literature, the puzzles had pulled her in. In solving them she was helping the characters in the story.

By the time they were nine or ten they were reading to themselves, often by torchlight after bedtime. Sally dived deep into fantasy – trilogies, tetralogies, quintets, none of which I’ll ever read. She became a connoisseur of the genre.

Once they started secondary school our nightly readings began to be interrupted. There were homework assignments, sleepovers, computers. We made it through the Inkheart and Wind On Fire trilogies. But during the second book of the Mortal Engines quartet we stalled. There was no point in reading if one of us wasn’t there. One night I realised it had been weeks since we’d all curled up on the bed together. I went back to reading other kinds of books, to myself.

One evening I heard an animated monologue coming from one of the bedrooms. It was Elsie, now twelve, reading aloud to her big sisters. They were sprawled about, Sally with her paper and pens, all completely absorbed in the story. They didn’t notice me. I lay down and listened.

Nick Bollinger

Nick Bollinger is a writer, critic and broadcaster. He has been a music columnist for The Listenerand presents the music review programme The Sampleron Radio NZ National. He is the author of How To Listen To Pop Music, 100 Essential New Zealand Albumsand Goneville, which won the Adam Prize for Creative Writing in 2015.

He lives in Wellington with his partner Kathy. Their three daughters have all grown up and left home.