Kristin Smith reviews the five Te Kura Pounamu finalists in this year’s NZ Book Awards for Children and Young Adults.

He kōrero Māori koe? He kōrero pukapuka koe?*

If you love reading te reo Māori, and you love reading fiction, you pretty much better love children’s books, or you’re gonna run out of reading material in te reo pretty quickly.

Luckily, children’s books in te reo can be especially clever, insightful, funny and surprising. I’ll never forget discovering Te Ātea by Katerina Te Heikōkō Mataira (honestly, what are we going to do now that we’ve lost her) and sitting on the library floor, quietly amazed that this picture book existed. It was written in te reo, in rhythmic epic poetry and the narrative begins with a nuclear holocaust and takes you on a journey of inter-stellar travel, a multicultural Māori-speaking society living deep underground, prophecies and wairuatanga, cannibalism, and establishing a utopian, vegetarian community on a distant planet.

I’m pretty interested in children’s literature in te reo for my own reading purposes, not just for reading to my six-year-old. But I did seek out some expert advice from her when I started looking at the following five children’s books, which are finalists for this year’s Kura Pounamu award for books in te reo Māori in the NZ Book Awards for Children and Young Adults. Anei ngā pukapuka hei pānui māku …

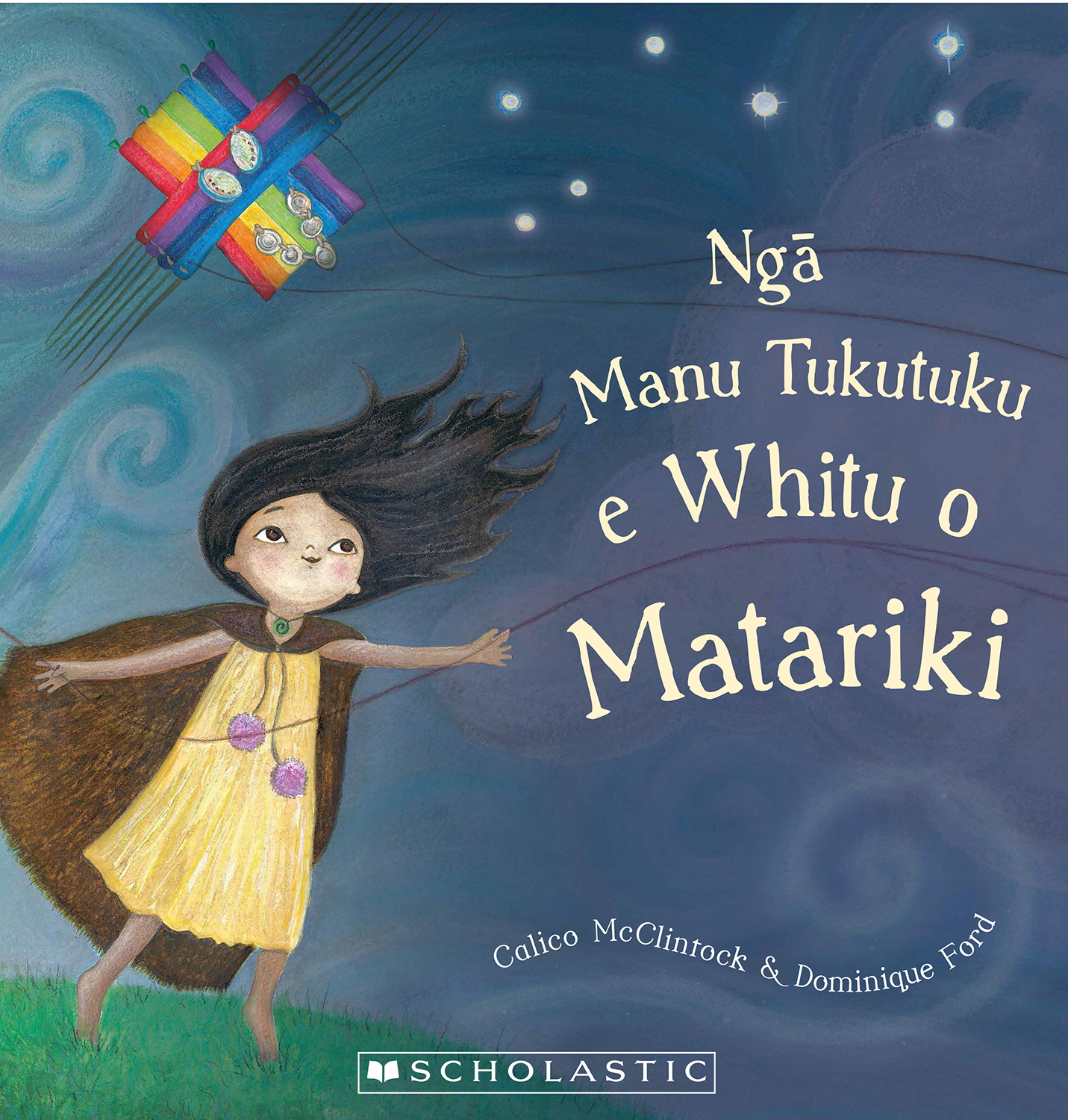

Ngā Manu Tukutuku e Whitu o Matariki was a complicated one to begin with. Matariki books are always pretty popular at Early Childhood Centres and schools, so I imagine that this one will probably do okay, sales-wise. It’s about seven sisters, in apparently pre-colonial Aotearoa who all make different traditional kites (manu tukutuku), each with a different shell for the eyes. The sisters are clearly based on the ‘seven sisters’ that are associated with Pleiades in Western mythology, combined with some of the stories about Matariki – the pōtiki of the whānau is called Ururangi. The kites end up getting blown up into the sky and become the seven stars of Matariki.

The beautiful illustrations and the visual and verbal repetition as we see each sister’s kite make for an easy read aloud. It’s also lovely seeing the different kinds of traditional kite. Ngaere Roberts’ translation is clear and flows along nicely – with just enough poetic language to make it feel interesting but keeping it clear enough for kids who might have just started school.

The subject matter is a tricky one though. I mean, most iwi already have a story of how Matariki came to exist, whether it’s Ngā Mata Ariki, the eyes of Tāwhirimātea, or Māmā Matariki and her tamariki, or another kōrero. It seems a complicated one to choose to rewrite, especially when the author has drawn from the Western ‘seven sisters’ story but forced it into a pre-colonial Māori time and space. It’s made even more tricky by the fact that only last year, Dr Rangi Mātāmua rocked our world by showing us that, in te ao Māori, Matariki actually has nine stars and not seven. Awkward.

NGĀ MANU TUKUTUKU E WHITU O MATARIKI

By Calico McClintock

Illustrated by Dominique Ford

Translated by Ngaere Roberts

Published by Scholastic NZ

RRP $18.00

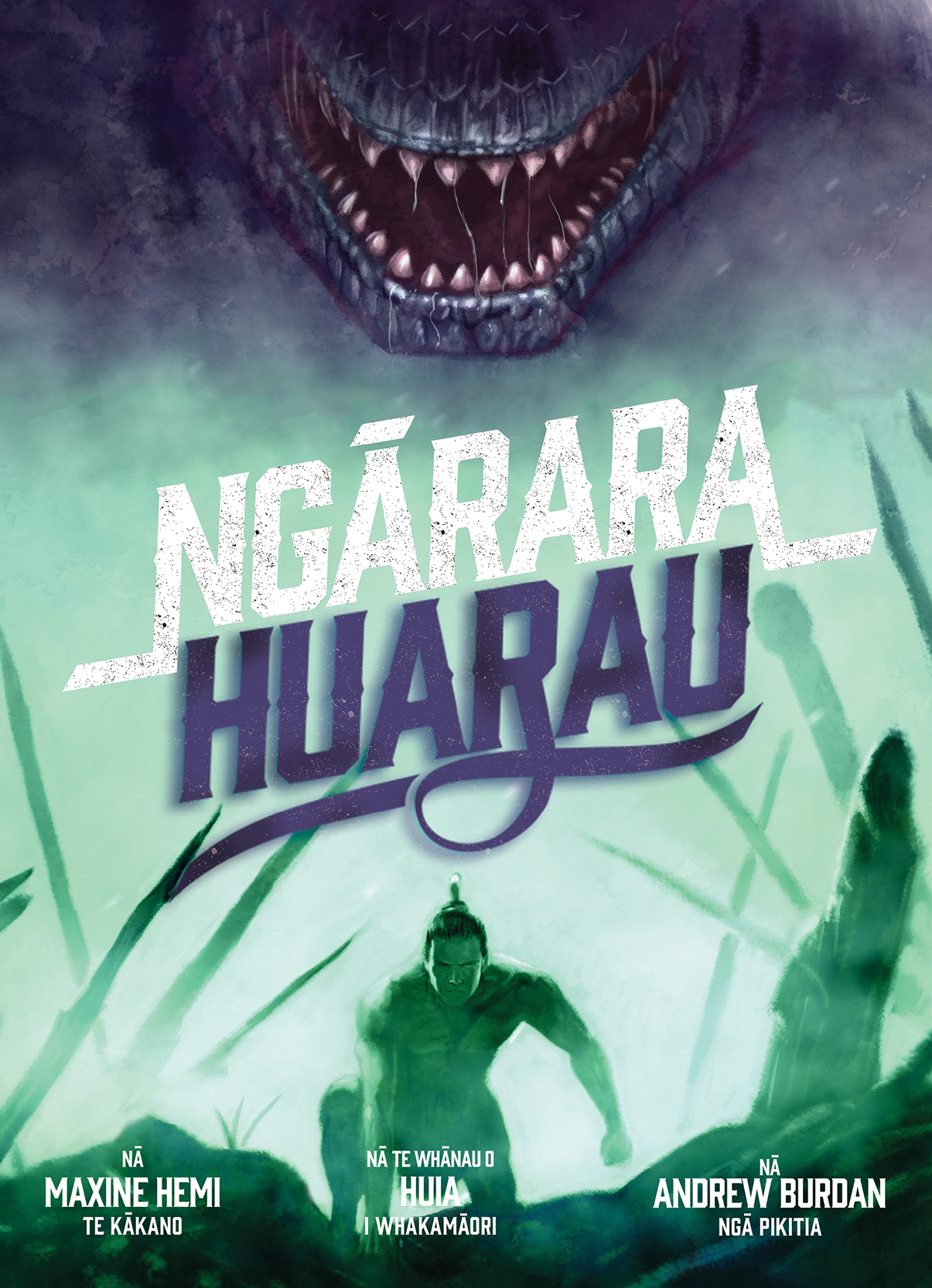

Ngārara Huarau was another kettle of fish altogether. If you like action-packed (but really short) comic book adventures, then this is the book for you. Andrew Burdan has illustrated a few graphic novels and shorter comic-style books like this for Huia Publishers, and his work always looks great. Like, every single page is honestly a work of art. If I wasn’t so against cutting up books, I’d be tempted to cut up this one and wallpaper my bedroom with it. The writer, Maxime Hemi, does really well considering how few words (and pages) there are to play with.

In a nutshell, a handsome warrior fights a people-eating, pā-destroying taniwha and thinks he’s defeated him but oooh, look closely on the last page and you might just be able to predict a sequel to this exciting adventure. My daughter wouldn’t even look at it (she is only six and it is pretty scary), but I liked it. I think bigger kids, especially kids who aren’t usually into reading at kura or at home, might get a kick out of this one. There is not very much time spent on building the narrative or the motivations for the characters, which is a shame, but really, this book is all about the action anyway (and it does seem like it might only be ‘part one’ of a series).

NGĀRARA HUARAU

By Maxine Hemi

Illustrated by Andrew Burdan

Translated by Te Whānau o Huia

Published by Huia Publishers

RRP $19.99

I really enjoyed reading this odd little pukapuka! Te Haerenga Māia a Riripata i Te Araroa was not at all what I was expecting. I looked her up, and apparently Maris O’Rourke has written a few stories about Riripata te kunekune (or Lillibutt, in the English language versions). You know how sometimes the best kids’ books are a little bit weird? Well, this book has that lovely tinge of strangeness to it.

Riripata lives at Te Rēinga, and she decides to walk along Te Araroa (a path that runs the length of the motu) to Tāmaki Makau Rau to visit her whanaunga at the zoo. The story was inspired by the author’s own walk along Te Araroa, and you can really tell that she has been on those whenua and engaged with the communities along her journey, just as Riripata does in the book. There’s a real genuineness to the way people and places are represented in this book (and I hear good things about her other books too).

Riripata travels from place to place in Northland, meets whoever is in that place and then continues on her haerenga. There’s some really sweet repetition each time she comes across a new group and they ask her to stay there with them, but even though she’s really tired, she always insists on sticking to her goals: ‘Kia ora, engari kāo, ka ū tonu au ki taku haere.’ The groups she meets range from kura kids at Paihia, to Captain Cookers in the ngahere at Herekino, to a Spanish speaking whānau on a campervan holiday (it’s funny how normal it seems now for Spanish and Māori to sit side by side – thanks, Dōra Mātātoa!).

He pīki whakanui tēnei ki te kaiwhakamāori, ki a Āni Wainui. Like nearly all of these books, Riripata has been translated from English, and Āni Wainui has done a really lovely job. It’s a pleasure to read – lovely lyrical language, but also really simple and straight-forward. I found that there were a fair few kupu I’d never come across before, hei tauira: ‘whare tāwhai/campervan’. But Wainui has used all these kinds of kupu so seamlessly that you never need to look anything up – it’s all clear from the context.

TE HAERENGA MĀIA A RIRIPATA I TE ARAROA

By Maris O’RourkeIllustrated by Claudia Pond Eyley

Translated by Āni Wainui

Published by David Ling Publishing

RRP $20.00

Whū! Hangareka ana! This book was really funny. Te Kaihanga Māpere is another stellar collaboration from Sacha Cotter (kupu), Josh Morgan (pikitia) and Kawata Teepa (whakamāoritanga). I remember when Ngā Kī came out, and how exciting it was to read a book in te reo that was so clever and inventive with language, pictures and with the whole overall kaupapa of the book. Ngā Kī won this category at the 2015 awards and I reckon this new offering from the trio is in with a shot too. It’s really clever and unexpected and, yeah, funny.

While most of this book is devoted to hilarious marble-making potions – ‘Ranua he pēke kāriki, me te niho kōura, kātahi ka takaia ki te tīhi nanekoti!’ – it’s really a story about following your dreams, and ends with a suggestion to the reader that they too might be able to get their name in Te Pukapuka o ngā Māpere.

Teepa’s translation is very funny and clever, and it can’t have been straightforward translating those complicated marble recipes. Sometimes it took me a while to work out what his kupu meant, but only because they’re so unexpected, and it was always worth the time spent pondering. The text is very rhythmic and he even manages to work in a few internal rhymes here and there. Kāore he painga i a ia mō te mahi whakamāori pēnei – kei runga noa atu ia.

Both Cotter and Morgan have done something truly beautiful in the way they write and illustrate Māori characters. I love how the kaihanga māpere is so far from your clichéd caricature of a young Māori girl, in both looks and personality (which of course makes her a far more truthful representation of Māori kids who are all diverse and unique individuals). She has scruffy red hair, khaki gumboots, a sheep called Winitana for a best friend, and she’s an inventor!

I’ll be looking out for more books from this team – they are taking people’s expectations for books about Māori kids and turning them upside down in the funniest possible way.

TE KAIHANGA MĀPERE

By Sacha Cotter

Illustrated by Josh Morgan

Translated by Kawata Teepa

Published by David Ling Publishing

RRP $20.00

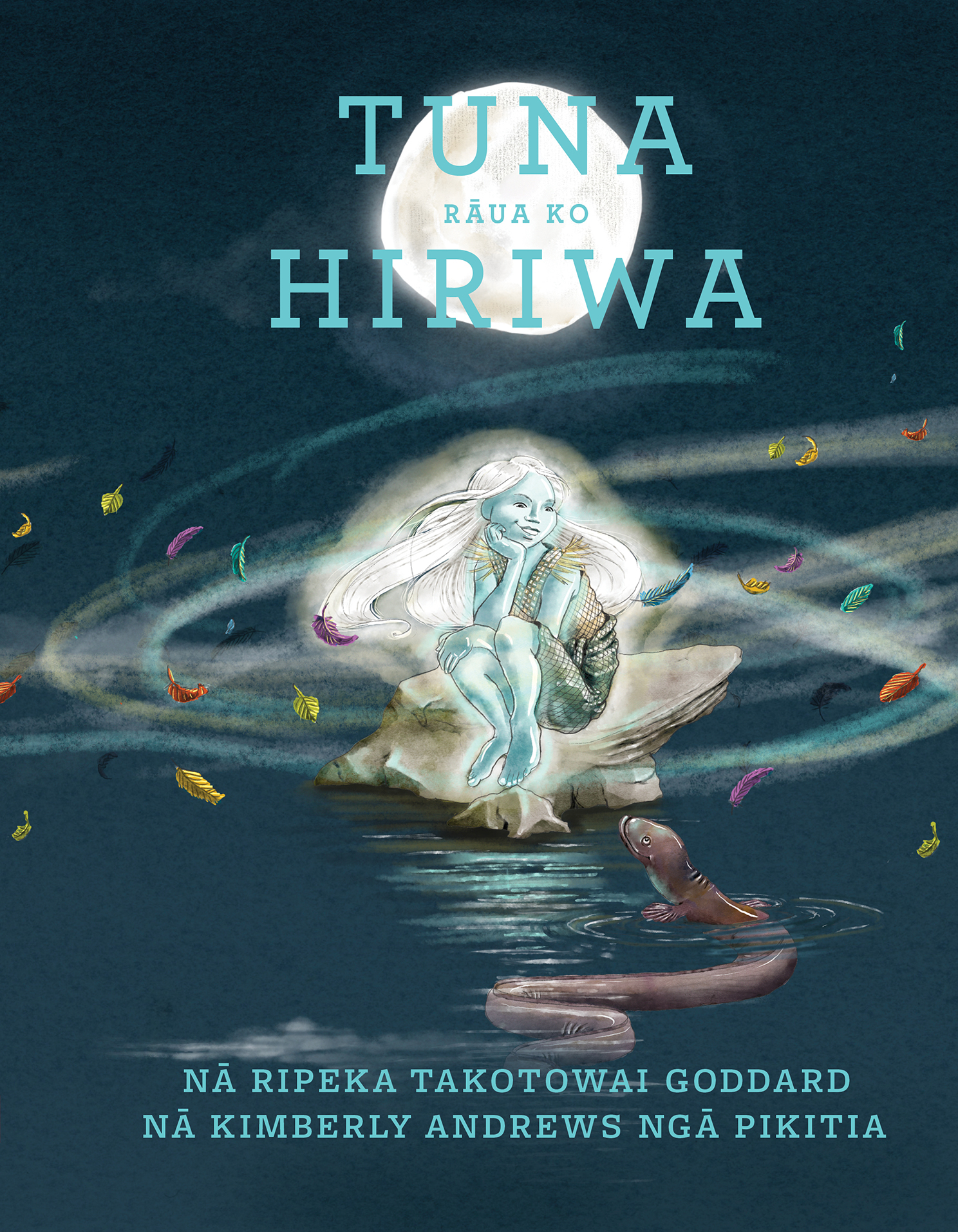

I’d like to give an especially big mihi to this book, as it appears to be the only one out of all five finalists which was written in te reo by the author, and not translated from English. In Tuna rāua ko Hiriwa, a tūrehu named Hiriwa befriends an eel who ultimately becomes jealous of her silvery (hiriwa) glow and eats her! It’s told like a pakiwaitara – explaining the how and why something in nature is the way it is. Te marama is angry that Tuna has consumed her mokopuna, Hiriwa, and banishes Tuna to the darkest parts of the awa. The story doesn’t pull any punches – my own sensitive wee six-year-old found it a bit scary when Hiriwa was killed and eaten – but it was that exhilarating kind of scary that you get sometimes with pakiwaitara, or with those grisly old Brothers Grimm tales.

The illustrations are what really captivated me and my kōhine – they are stunning. The expressions that Kimberly Andrews shows on the faces of Tuna and Te Marama especially are just so, well, expressive! Waihoki, E ai ki taku kōtiro: ‘Te ātaahua hoki o te patupaiarehe e Mā!’

TUNA RĀUA KO HIRIWA

By Ripeka Takotowai Goddard

Illustrated by Kimberly Andrews

Published by Huia Publishers

RRP $20.00

I loved that all the books that are finalists in this category are written for speakers of te reo, rather than monolingual kids/teachers/parents looking to branch out with a little bit of Māori. I do think it’s super important for non-speakers to read more in te reo, but we actually have quite a lot of children’s lit in Māori that is already aimed at that level (check out the Reo Pēpi series or the Te Reo Singalong series or Huia’s First Readers in Māori). It’s nice to see new content is being created for kids who aren’t learning the language, they’re living the language.

Reading all these award nominees for this review also made me pine for more books – childrens, young adult, adult or whatever – to be written in te reo first and foremost, rather than written in English and then translated. Not at all to slight the amazing translators’ work on these books (Kawata Teepa, especially, did an unbelievably creative translation of Te Kaihanga Māpere), but just that a book feels really different when it is created in te reo and written for a Māori-speaking reader.

What I’m left wondering is if we might see some books authored by some of those amazing translators in the near future. I hope so. When you read a book that was written in te reo, everything just sits differently, fits differently. I want to see more of those books on our shelves, and I want our national literary awards to have more space for them. Ki te hoe!

*Did you know ‘kōrero’ (alongside ‘pānui’) was one of the first kupu Māori used to translate the English idea of ‘reading’?

Krissi Smith

Kua roa a Krissi e noho ana i Te Whanganui a Tara nei, i roto rawa i te rohe o Te Āti Awa nō runga i te rangi. Heoi, nō Kōterani kē ōna tīpuna - he tangata mau panekoti, he tangata noho maunga, he tangata whai huruhuru! Kotahi tāna tamāhine haututū - ko Nina Manaia te tou tīrairaka. Nō Rongomaiwahine, nō Ngāti Kahungunu, nō Te Āti Haunui a Pāpārangi hoki tāna hoa wahine. Kua waimarie ia i tana mōhio ki te reo Māori, he taonga nui i kohaina mai i ōna pouako, i ōna tuākana, i ōna hoa anō hoki. I ēnei rā, he kaiako reo Māori ia, he kaituhi, he kaiwhakahaere tānga hoki ki Te Whare Ture Hapori o Te Whanganui a Tara me Te Awa Kairangi. Engari, ko tana tino hiahia i tēnei wā, ko te takoto noa i te moenga mō te rā katoa, pānui pukapuka ai.