In the current Anglo-Saxon book market, there is much that is the same. If one book is successful, there’s a flurry to find another one just like it. Sameness can make us all feel safe, but Julia Marshall from Gecko Press reckons sameness isn’t enough.

A diet of one thing becomes tiring, in the way that cabbage is very good as a vegetable, but not if you are on an all-cabbage diet. Even the books in our bookstores that are not local come mostly from the same place: the UK, rather than from other English-speaking markets – evidenced by the pound price on the back cover.

A good book is a good book

As Gecko Press founder, publisher, and sometimes-translator of books, I believe that a good book is a good book, regardless of where it comes from. Good doesn’t mean ‘literary’ – to me, it means good in its genre and for its purpose.

When reading a book in translation – or indeed any book that is written outside our own experience – we willingly put ourselves into the shoes of another, go to a sometimes wild and strange place, and enjoy the fact that people do things differently there.

Good doesn’t mean ‘literary’ – to me, it means good in its genre and for its purpose.

How could we not want to access the work of the best writers and illustrators in the world, regardless of what language they speak – whether that language is French or Chinese, or te reo Māori? Many of us read only one or two languages, and the only way to access books from other cultures and languages is to read them in translation.

In English, we associate ‘translation’ with what is ‘lost’ and somehow we think a translation must be inferior. But a good translation should have us forget that we are reading something in a different language. Pippi Longstocking works equally well in English and in Swedish – and it has been translated into more 70 languages.

The early days of translated European books

In New Zealand, back in the sixties, we used to get lots of books translated from the rest of the world – Pippi Longstocking, of course, and Emil the Detective, and Mrs Pepperpot, Babar and Heidi.

Back then, we had no local publishing industry to speak of, and we were crying out for more books that told our own stories; and we are still crying out for more stories about us and our place in the Pacific. We need the stories of Joy Cowley and Kate De Goldi and Gavin Bishop and the many great writers and illustrators that New Zealand has produced, and we need our own myths and legends and histories that are at the heart of us. But we also need stories and books from other cultures and writers.

Different countries bring with them the richness of their own back-stories, culture and history.

What we can learn from other cultures

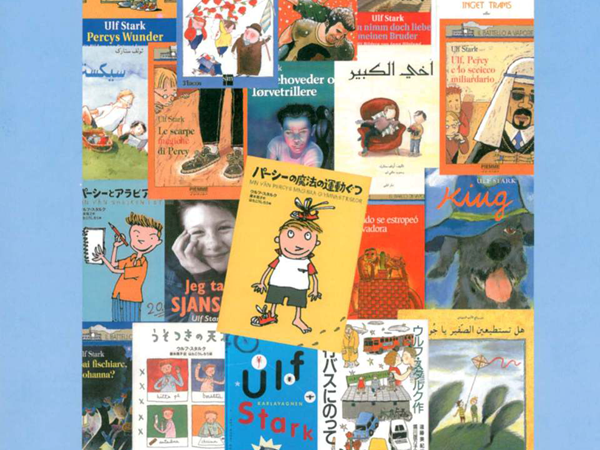

When Gecko Press began in 2005, only one percent of books published in the UK were reported to have non-English beginnings. When I reported this number to the Swedish publisher of Margaret Mahy, he said: ’I’m surprised that figure is so high.’ In Europe, this figure varies from 25–40 per cent (though it is apparently a whopping 70 percent in Slovenia).

In our current political climate, it is more valuable than ever to read from within cultures of others.

In our current political climate, it is more valuable than ever to read from within cultures of others. It can also be a political act to forbid the translation of writers into other cultures. Currently China has ‘suggested’ that publishers cease publishing foreign books, including those for children. Free access to books and other cultures is a sign of a healthy democracy.

Books from other cultures can bring a different sensibility. The late John McIntyre of The Children’s Bookshop in Wellington once said in a speech: ’In Europe, picture books have a tradition of appealing as much to adults as they do to children, and many subjects we would avoid here are freely discussed and regularly published right across the Continent. There seems to be a healthy respect for the mental strength of children to handle difficult issues without the fear of Child, Youth and Family coming to check your bookcases. Either that or they think a bit of Teutonic mental trauma is good for the development of the child. Remember, it was a German who wrote Struwwelpeter and the poem “Little Johnny Suck-a-thumb”, where the wicked scissor man came and snipped your thumbs off if you sucked them.’

We cannot generalise about books by country, but culture will find its way in.

The best Japanese children’s books, for example, are often very child-centred and warm, and achieve perfect simplicity. French books can be quite beautiful and wacky, or hilarious and sometimes without noticeable plot. They have a lot of love in them. Scandinavian ones are often a little rebellious. They have a style of illustration called ‘pretty-ugly’ that is fun. They sometimes use a soft, gentle palette, perhaps because their sun is not as harsh as ours, and often perspectives and composition and faces can be a bit wonky.

The best Japanese children’s books, for example, are often very child-centred and warm, and achieve perfect simplicity.

Be adventurous

In this book ecosystem, where everything depends on everyone and everything, publishers need our libraries, bookshops and schools to be adventurous in the books they choose – and we need to encourage readers to seek them out and sometimes to choose a book that is not from a writer they know, perhaps one with a hard-to-pronounce name.

We want to build readers who want salt and pepper and garlic and butter and chilli and vinegar and maybe even, heaven forbid, a little sugar with their cabbage. Same, and not-same. Safe, and not-safe. Sauerkraut or dumplings or just plain cabbage.

Editors’ note: The Reckoning is a regular column where children’s literature experts air their thoughts, views and grievances. They’re not necessarily the views of the editors or our readers. We would love to hear your response to any of The Reckonings – join in the discussion over on Facebook.

Julia Marshall

Julia Marshall is the Publisher and Owner of Gecko Press, an independent publisher based in Wellington. Every year Gecko Press translates and publishes 15 or so carefully selected children’s books by some of the world’s best writers and illustrators, from countries including France, Germany, Japan, Poland, and the Netherlands. Gecko Press also publishes three or four original New Zealand books each year.