Incredible poet and children’s fiction writer James Norcliffe reviews two books by Gecko Press, translated from the Swedish.

Soda Pop is a Swedish classic, first published in Swedish in 1970, and took Norcliffe back to his days listening to The Goon Show with his grandfather. The translation is by Sarah Death.

The Ice Sea Pirates is vaunted as a ‘modern classic’, and is a quest story, about a 10-year-old girl who sets out to save her sister from the most vicious pirates of them all: the ones that steal children. The translation is by Peter Graves.

Soda Pop, by Barbro Lindgren, with illustrations by Lisen Adbåge (Gecko Press)

When I was a small boy I would sometimes find my grandfather, ears glued to a wooden console radio, laughing with tears streaming down his cheeks and arms slapping his thighs. He was listening to his favourite programme – The Goon Show. I quickly learned to love it too: the outlandish plots, the bizarre characters, the language jokes and sound effects, the whole lunatic surrealism was utterly wonderful, utterly original.

Reading Soda Pop, Barbro Lindgren’s classic children’s story first published in Swedish in 1970, was very much for me a return to those Goon Show days. The story, such as it is, is delightfully bizarre. Soda Pop is the father in a multi-generation family, including his son, Mazarin, his father Dartanyong (who lives in the woodshed and whose name allegedly means feeble in Spanish) and Dartangyong’s grandfather who lives in the top of a nearby fir tree. There is also a wild menagerie including a giraffe who lives on Soda Pop’s rubbish heap and a ‘huge swarm’ of wild tigers who spend most of the book locked in the barn, although a running gag has Soda Pop regularly paying a hot dog man two tigers at a time for hot dogs to feed to the tigers. There are pike and owls.

The story is episodic, each section of craziness following on in bite-sized chapters, nicely designed for reading aloud; that is if the reader can keep a straight face. It’s a third person narrative told in a deadpan story-telling style. We are introduced to Mazarin first although he plays no central role in the story. He is ‘…a chubby red boy. He has tiny little kind eyes, big red ears and droopy cheeks … he eats buns, reads comics…’.

The story is episodic, each section of craziness following on in bite-sized chapters, nicely designed for reading aloud; that is if the reader can keep a straight face.

If Mazarin is unprepossessing, Soda Pop is bizarre. Passionate about orange, when we first meet him he is under the red table, a ‘…rather fat, rather lazy dad … a really great dad – he couldn’t care less about anything…’ He spends most of the book wearing an orange bathrobe and sporting a tea cosy on his head. Identities are as odd as names. His great grandfather in the fir tree believes he is a cuckoo. Dartanyong believes he is a flying trapeze artist, then a master painter and later a plumber and later still a pop artist. At another point both Dartanyong and Soda Pop fall into the delusion that they are dogs.

Other characters come and go: the hot dog man, the cross old man who believes Soda Pop is stuffing his letter box with owls, and Gustav the burglar. Meanwhile, the giraffe carries on munching through just about everything including all the beds in the house, and the tigers in the barn add tension and mayhem. And so it goes, craziness after craziness and all tremendous fun.

Meanwhile, the giraffe carries on munching through just about everything including all the beds in the house, and the tigers in the barn add tension and mayhem.

This is a beautiful book living up to the splendid production standards that have become the hallmark of Gecko Press publications. It is the first time the book has been translated into English and in the translation by Sarah Death the story rollicks along as one assumes it must have done in the original Swedish. She does a nice job, too, in translating Swedish comic neologisms into English: decrepitigers; telliphones… An innovation in this edition is the introduction of a generous number of illustrations by the young Swedish illustrator Lisen Adbåge. Her brightly coloured faux-naif drawings complement the tone of the story perfectly.

I can’t remember any female characters in The Goon Show. Perhaps Soda Pop is showing its almost fifty years by not featuring any females either. A woman – naturally ‘red with yellow hair’ – is the only female mentioned (on page 28) when Soda Pop is interviewed for a job. He doesn’t take it.

For all that Soda Pop is a wacky ride, giving the lie to Sweden’s Ingmar Bergman-like reputation for darkness and gloom. If it harks back to Spike Milligan, it may well be the grandparent of the wacky modern adult novels of Jonas Jonasson.

The Ice Sea Pirates, by Frida Nilsson (Gecko Press)

How appropriate it was that, as I was setting out to put this review of The Ice Sea Pirates together, the first polar blast of the winter swept up New Zealand bringing howling winds, teeming rain and hail and flurries of snow.

The Ice Sea Pirates is utterly imbued with these things. Swedish writer Frida Nilsson has set her story in an archipelago in the imaginary Ice Sea, so bleak and so far north that the sea itself freezes over in winter. The original novel was published in Swedish a couple of years ago, and this year sees the English version released. It has been beautifully produced by Gecko Press and has been translated by Peter Graves with a number of black and white illustrations by David Barrow.

It is a quest story. The opening chapter quickly and efficiently sets the scene and pushes the story off. It is a first person narrative and our storyteller is Siri, a ten-year-old girl living with her father and younger sister Miki in Blue Bay where it is so cold in winter that birds can freeze in mid-flight. The mild fantasy elements that occasionally feature later in the story are foreshadowed by the description of a piece of a mermaid’s flipper mounted on the wall. The father had once caught this in his fishing net. This gives an opportunity for Siri to explain at once one of the presiding themes of the book – the coexistence of good and evil – and of the ever present danger of those who personify the latter: ‘…you see, there are some people who believe there is no difference between catching a cod and catching a mermaid. Or doing even worse things. Where I live, there was a time when pirates roamed the sea. Foul, wicked pirates…’

The mild fantasy elements that occasionally feature later in the story are foreshadowed by the description of a piece of a mermaid’s flipper mounted on the wall.

Siri then tells her little sister what she knows of Whitehead, the most vicious pirate of them all. ‘…There’s a man who treats children as if they’re animals. And inside that man, in the place where other people have a soul, there’s a space as empty and cold as an ice cave…’

The soulless Whitehead, soon to become the great adversary in the story, has a particular passion – children, ‘… small, thin children, the smaller the better. Whenever the pirates get hold of small children they throw them straight into the ship’s hold…’

Siri tells Miki that the fate of such children is to be forced to work from morning till night in the dark depths of Whitehead’s diamond mines. The first chapter ends on this portentous note: ‘all this seemed no more than a fairy tale… I would never have believed for a moment that Whitehead would sink his claws into my little sister…’

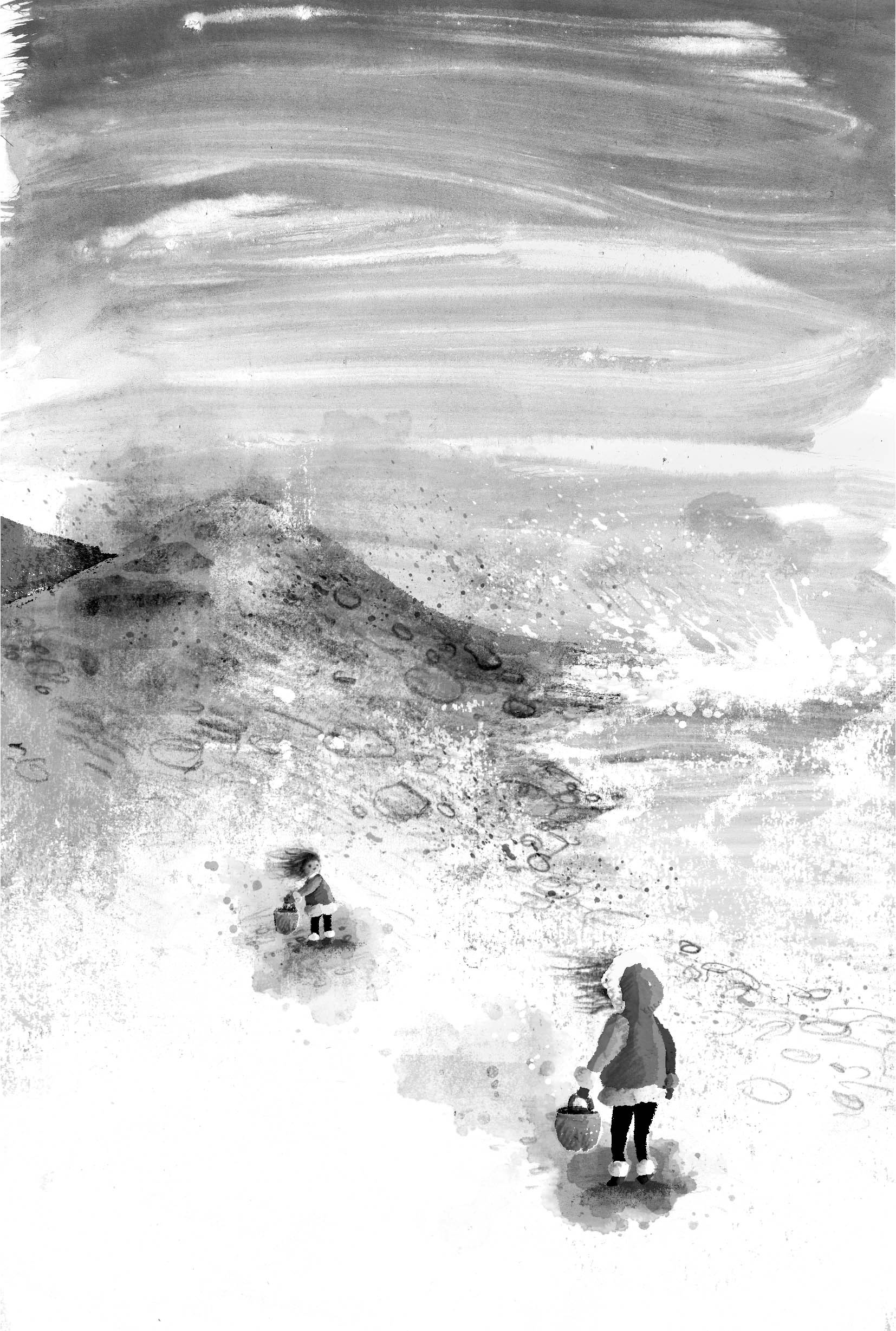

In this way the reader is groomed for a situation as bleak and as bone-chilling as the climate. Sure enough, in the very next chapter, Miki – small, thin Miki – is snatched by Whitehead’s pirates. She and Siri have gone to a tiny island to gather snowberries and because the berries are few, Siri sends Miki off on her own to the other side of the island where she is promptly abducted.

… the reader is groomed for a situation as bleak and as bone-chilling as the climate.

This is of course a moment of horror for Siri (and the reader) compounded by the fact that she, having ordered the unwilling Miki to the other side of the island, was largely responsible for what happened. The guilt this engenders helps explain the single-minded tenacity that drives her to find and rescue her little sister before she perishes in Whitehead’s diamond mines.

Siri’s quest, by any objective standard, faces insurmountable odds: a ten-year-old girl on a rescue mission with dozens of blood-thirsty pirates, an ice-bound ocean, inhospitable islands often with equally inhospitable inhabitants, sceptical sailors – not to mention ferocious wolves, ambiguous mermaids, savage bogle birds and the nightmarish Whitehead himself all pitted against her. Moreover, Siri has no idea where Whitehead’s diamond mine is. His island redoubt is mysterious and its location unknown.

All this, of course, makes for almost non-stop action and page-turning excitement. Perhaps just as well, for if the pace were a little slower, the more sceptical reader might at times find things a little too implausible; disbelief not entirely suspended.

It is a violent and unpredictable world that Siri finds herself in. People regularly reach for guns and knives, and killing is not far away. Life preys on life in this harsh world. While the violence is incipient as far as Siri personally is concerned, the reader is aware that it is a constant undertone and this gives the book an edgy, often worrying frisson.

It is a violent and unpredictable world that Siri finds herself in.

Siri is an attractive heroine: smart, sassy and resourceful. Just as the course of her journey hops from island to island in the archipelago, so her adventure hops from crisis to crisis. She does find support from the kind-hearted ship’s cook Fredrik, but for the most part she is on her own in a hostile, frigid environment.

The ending, and Miki’s rescue, has a succession of skilfully engineered surprises and is very satisfying. The Swedish Daily News described The Ice Sea Pirates as a “modern classic” and while that is an overused term, in this case it is more than justified.

Soda Pop

By Barbro Lindgren, with illustrations by Lisen Adbåge

Published by Gecko Press

RRP $24.99

James Norcliffe

James Norcliffe is a poet, fiction writer and educator. He has written collections of poetry and short stories, and several books for young adults. His writing has been featured in journals and anthologies, and he has also worked extensively as an editor. Norcliffe has won awards and prizes, and has been the recipient of prestigious fellowships, including the 2006 Fellowship at the University of Iowa. For his children’s book The Loblolly Boy (2009), Norcliffe won the Junior Fiction Award at the 2010 New Zealand Post Book Awards for Children and Young Adults.