Ko tēnei Te Wiki o te Reo Māori! All week, our guest editor Nadine Anne Hura (Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi) will bring us literary insights and treasures from Te Ao Māori.

First up, she draws back the curtain on the production of picture books in te reo, and discovers some magicians at work.

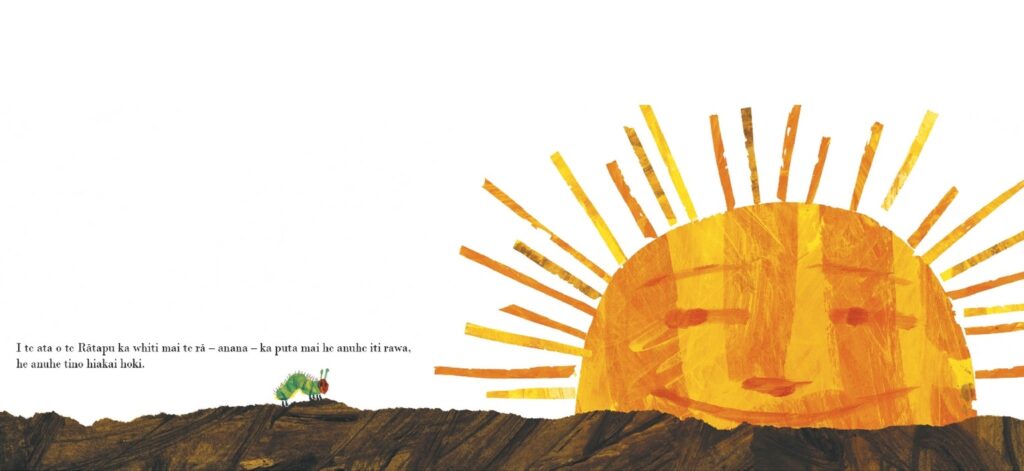

In 1992, Brian Morris, a school teacher by trade, bought a copy of Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar, and, breaking all the rules of copyright, covered up all the English words and replaced them with Māori.

Te Anuhe Tino Hiakai became a solid favourite in his whare, along with many other classics he has translated since then. ‘They were great books in English,’ he says. ‘Why wouldn’t they be great books in Māori? Maybe even better books in Māori!’

A few years later, in 2007, Brian was at the Bologna Book Fair when he came across the familiar illustration of a long, green caterpillar marching across a white book cover. His eyes went immediately to the text, but the title wasn’t in English. He stopped to chat to the agent, who boasted that the The Very Hungry Caterpillar had been translated into 28 languages.

‘Twenty-eight?’

The agent nodded.

‘But not into Māori?’

The agent shook his head.

And Brian thought: ‘Not yet’.

When Brian got back to New Zealand, he floated the idea of translating The Very Hungry Caterpillar into Māori with the Directors of Huia Publishers, where he worked. At first, they needed a bit of convincing. Would there be a demand for classic picture books published in Māori? How easy would it even be, to translate something like The Very Hungry Caterpillar? Brian pulled out his worn-out old copy of Te Anuhe Tino Hiakai. “I’ve already done it,” he smiled.

It would be a few more years before the glossy pages of Te Anuhe Tino Hiakai finally rolled off the printer, but as soon as they did, there was no looking back. Since it was first published in 2012, almost 7,000 copies have been sold. Huia has gone on to publish many more classics, including such famous titles as Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak (Kei Reira Ngā Weriweri), Who Sank The Boat? by Pamela Allen (Nā Wai Te Waka I Totohu?) and We’re Going on a Bear Hunt by Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury (Te Haere ki te Rapu Pea).

These days, Brian co-owns Huia along with Eboni Waitere, and publishing books in te reo remains a core part of their business. But things are a far cry from when he was a teacher in Hawkes Bay in the 80s.

Brian’s tamariki were among the first generation of kōhanga reo and kura kaupapa kids. These were trailblazing days in language revitalisation, a time when parents who signed up for immersion education knew that if there was something they wanted for their kids, they’d have to go and get it for themselves. That’s where translation of reo Māori children’s books really began.

Back then, practically all the resources issued for young people by the Department of Education were in English, so the community had no choice but to use what they had. ‘Someone would be put in charge of the translation, someone else would type it up, then it’d be photocopied and enlarged, cut out, and stuck into the books on top of the English.’

Nowadays, there are whole sections of the library dedicated to Māori books, and prestigious awards to celebrate books in te reo, such as Te Kura Pounamu, the award for the best book in te reo. This year, Huia took out the top honour at the New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults for Te Kaihanga Māpere by Sacha Cotter and Josh Morgan.

The translation of Te Kaihanga Māpere was done by Kawata Teepa, a native speaker an author who’s translated more books than he can carry. Surrounded by all his books, Kawata says there’s a special kind of magic that goes into translation. ‘Growing up in Rūātoki, we only spoke Māori. I remember when I first heard books in English, sitting around listening to Bad Jelly the Witch on the radio. I think I was about eight years old at the time. I could hear the language coming alive through the words. It was like going on a journey.’

Preserving that magic is what Kawata strives to do in his translations. He gives me some examples of the use of onomatopoeia from Te Haere ki te Rapu Pea (We’re going on a Bear Hunt). ‘Kūwehi’ and ‘kūwera,’ he explains, are transliterations for squishy and squelchy, while ‘hūwihi’ and ‘hāwihi’ are transliterations for swishy and swashy. Other words slot seamlessly into the story while staying absolutely true to whakaaro Māori. ‘Roly-poly,’ for example, is to ‘taka-porepore’ – to fall and roll over and over. It’s a reminder that reading aloud should be fun.

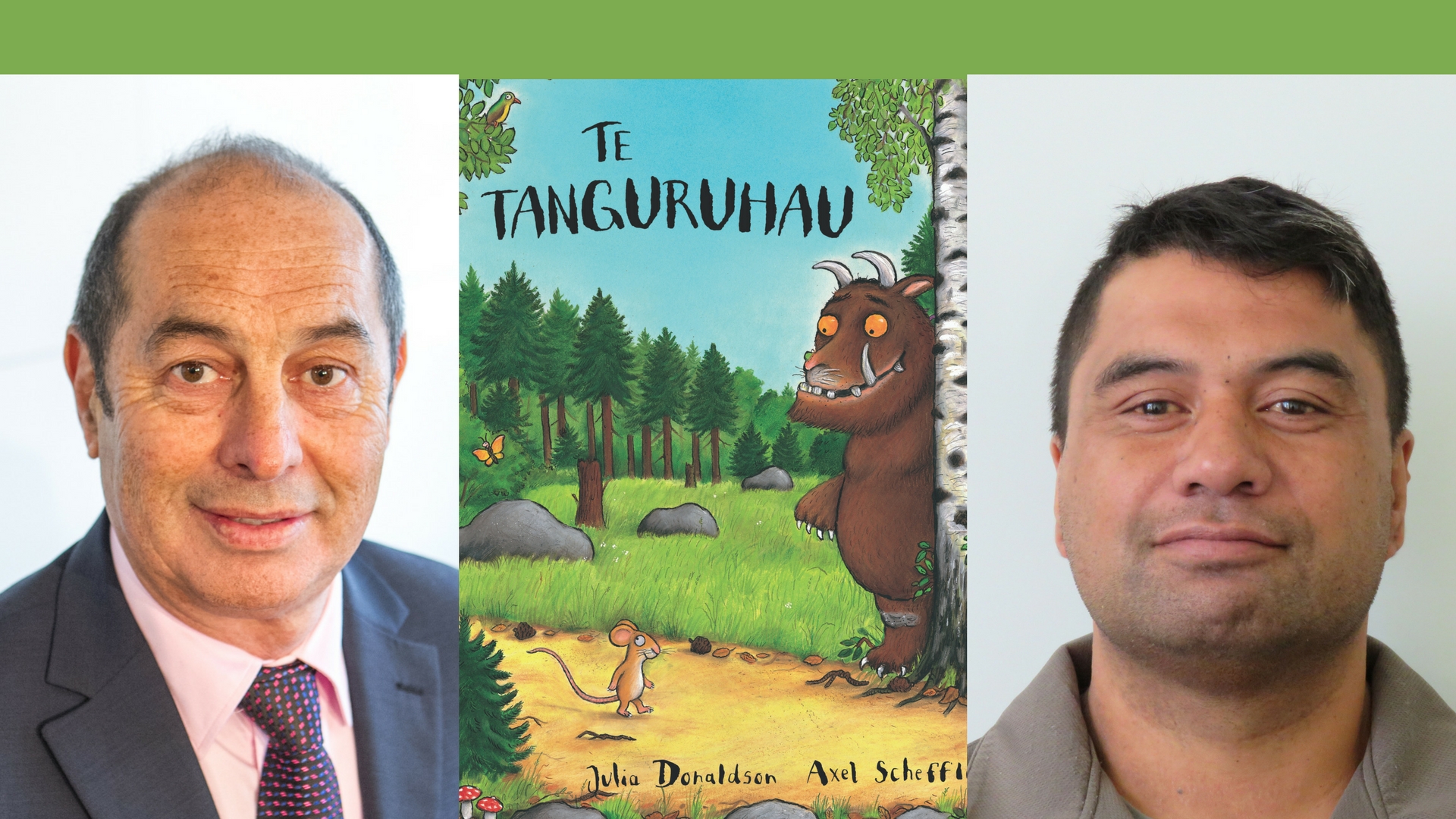

It was certainly entertaining listening to Brian read from Te Tanguruhau by Julia Donaldson (The Gruffalo). As I took the story in, I was struck by just how much it sounds like the original. It seems like a ridiculously obvious thing to say, but for some reason I had assumed that it would be impossible to achieve the exact same rhythm and rhyme in a different language.

It’s a mistake a lot of people make. ‘People often have this very narrow view of what te reo can do. People think that Māori stories amount to myths and legends. But that’s such a limited perspective. Our language has incredible range. We can traverse all genres and styles. We can do anything with te reo, and do it well.’

Our language has incredible range. We can traverse all genres and styles. We can do anything with te reo, and do it well.

That’s not to say it’s easy. But the challenge, Brian says, is the most exciting part. ‘Preserving the integrity of the story is paramount. Is it playful? Is it sad? Is there suspense? You need to find that emotion, and be true to it in your translation.’

Brian talks about the importance of each word and turn of phrase, describing the process of capturing whakaaro Māori within the context of a story that at times is both foreign and fictional. It can be especially tricky when encountering words with double meanings, or expressions that play with metaphor. Carrying those layers across from one language to another is crucial, and requires mastery of both languages.

The word Tanguruhau, for example, just like the word Gruffalo, is a completely made up word. ‘It needs to be an invented word,’ Brian explains, ‘because The Gruffalo, as we all know, is a figment of the imagination of that koi little mouse. It couldn’t be a word in Māori that people knew, because then the story wouldn’t work.’

Broken down, ‘tanguru’ means to be deep-toned, or gruff. The word ‘hau,’ has many meanings, from breath to breeze to essential vitality. More importantly, it also happens to be a very handy suffix to use in Māori because the ‘au’ sound is so common. Given that the genius of The Gruffalo is in its rhyme, it was essential to find the right word on which to build the entire story through and around.

It’s precision art, with purpose.

‘That’s the thing,’ says Brian. ‘A good story is a good story, is a good story. The language is just a vehicle. As a translator, your job is to serve the story. Conveying meaning is only one aspect of translation. You also need to think about how something sounds when it’s read aloud. Is it entertaining? Does it delight and inspire? If it doesn’t, then you’ve missed the mark.’

Looking back to those pioneering days of translation, when ‘cutting and pasting’ meant literally cutting and pasting, it feels like we’ve made remarkable progress in the last thirty years.

Then again, there’s always more work to be done. On Brian’s desk, I spy a copy of The Gruffalo’s Child. I ask him if the reo Māori version is due out any time soon.

He smiles and shakes his head. ‘That one’s parked,’ he says. ‘For now.’

Tune in everyday this week for more features in honour of Te Wiki o te Reo Māori. Tomorrow, Kristin Smith writes a love letter—in te reo—to a YA classic.

Nadine Anne Hura

Nadine Anne Hura (Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi) has a background in journalism, education policy and kaupapa Māori research. Her essays explore themes of identity, biculturalism, politics and parenting, and are collected on her website.