The follow-up to the award-winning Annual is out this month, ready to be part of the formative childhood reading of a new generation of Kiwi kids. We reviewed it last week, but we have also asked a few of the contributors to Annual 2 what books made an impact on them as children. Here are Steph Matuku, Michael Petherick, Gavin Mouldey, and David Larsen.

Steph Matuku won the 2017 Pikihuia award for best extract of an unpublished novel, and is the author of the screenplay ‘Garage Sale’ in Annual 2.

Steph spent fifteen years writing radio advertising, before deciding to branch out and write pieces that were longer than thirty seconds. She has a special love for writing stories for children and young adults and has written for film, magazines and theatre.

In 2016, Steph won a place on the Māori Literature Trust’s writing incubator programme ‘He Papa Tupu’, and wrote her first fantasy novel for young people, Flight of the Fantail, to be published by Huia Publishers. She has two children, a messy house and lots of books.

These are the books that formed her childhood:

The Man who was Magic, by Paul Gallico

This is a beautiful tale of a town of stage magicians who become fearful and jealous when a real magician arrives in their midst. It was the first entertaining childhood story I’d ever read that was also quite deep and literary at the same time. It seemed marvellous and eye-opening to me that the world was indeed a magical place to be – if only one knew how and where to look for it.

The Adventure Series, by Willard Price

Hal and Roger travelled the world capturing animals for zoos (they were only kids! How were they allowed to do this?!), and I thought their lives were so much more interesting than mine. They got to fight poachers and dive for pearls and battle blood-crazed lions and keep cheetahs for pets. My tortuous weekly piano lessons were pretty tame in comparison.

The Silver Crown, by Robert O’Brien

This was the first truly sinister book I’d ever read. Oh yes, there were the Grimm Brothers, but their dark tales were wrapped up in gingerbread houses and talking animals. But The Silver Crown is a contemporary novel, where adults under the thrall of a black crown, turn kids into terrorists. In the first few pages, our heroine’s house is burnt down with her family in it. Thrilling and terrifying.

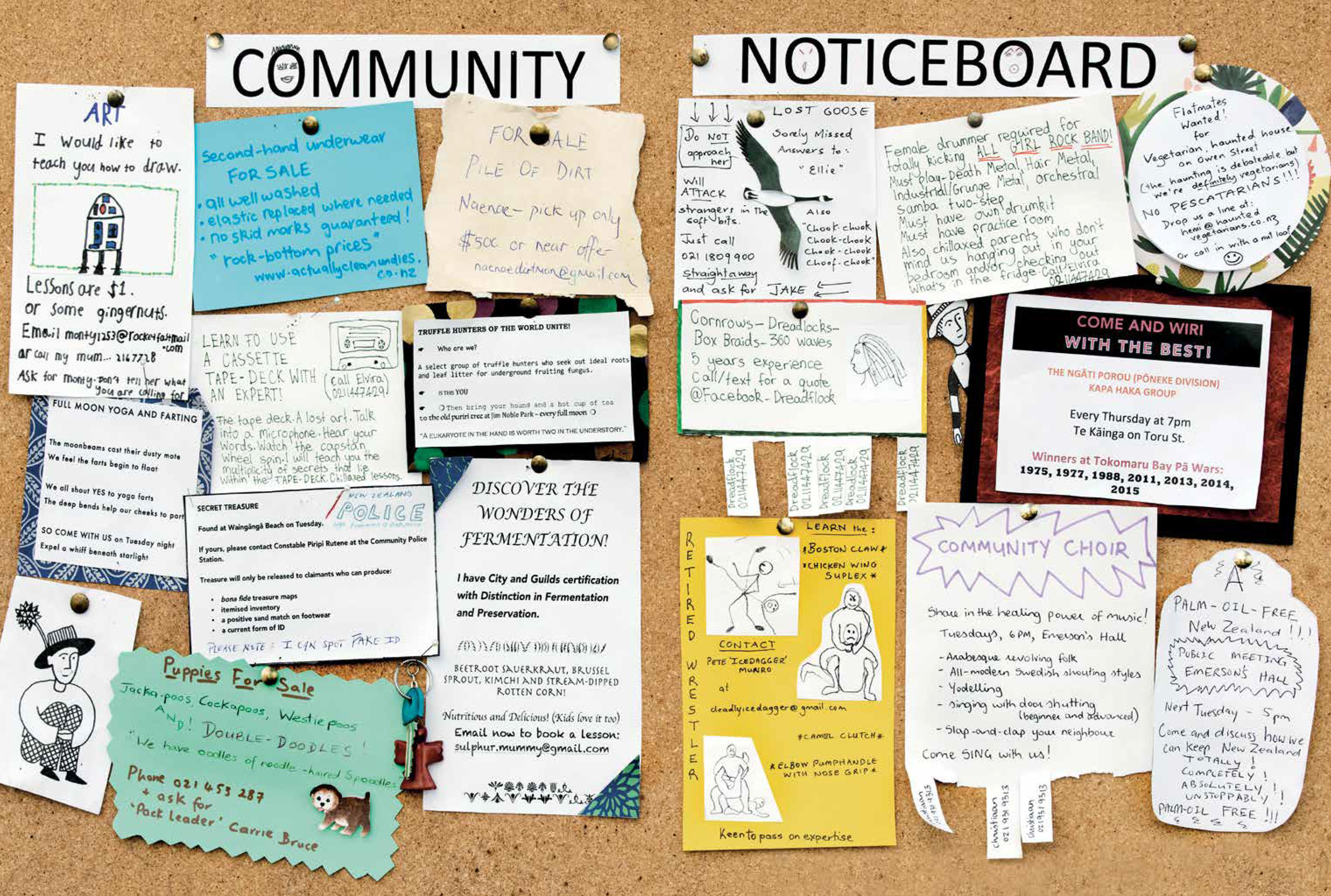

Michael Petherick is an award-winning writer and musician who grew up in Whangarei and now lives in Wellington with his wife and two children. He writes for children and adults, and after putting his children to bed he makes electronic beeps in dance punk band Lovers in Monaco.

He is currently working on a children’s album that he describes as ‘a mash up between Yo Gabba Gabba, Daft Punk, and R2D2 noises.’ He created the ‘Community Noticeboard’ (above) in Annual 2.

These are the books that formed his childhood:

I grew up in Northland in the 1970s. We didn’t have many books in the house. Mum and Dad knew I read a lot, so they took me to the library and left me by myself while they went shopping, or to the Men’s Club across the road. The librarians didn’t care.

I read everything in the children’s section and then moved on to the adults’ – Wilbur Smith and Shirley Conran – when I was still at intermediate. Someone gave me C.S Lewis’s A Horse and His Boy for Christmas when I was eight. I must have read it fifty times; over the school holidays hiding in the caravan at the beach, in my room during winter because it always rained. I knew every word – that Shasta would meet Aravis, his future wife, on page 50 and escape from the Calormen; that on page 212 they would be chased through the desert by a lion.

We had a book called The Children’s Encyclopaedia and I read it over and over. It was full of excerpts of novels, but I thought they were short stories because we didn’t have any other books.

Years later I went to university and a woman took pity on me and loaned me The Hobbit. She was my future wife as well, but like Shasta I didn’t know it at the time. In the middle I found a story from the Encyclopaedia I had already read a thousand times, about Bilbo meeting Smaug the dragon. It was the best book ever written. It was so good it made me cry. Then she loaned me Lord of the Rings.

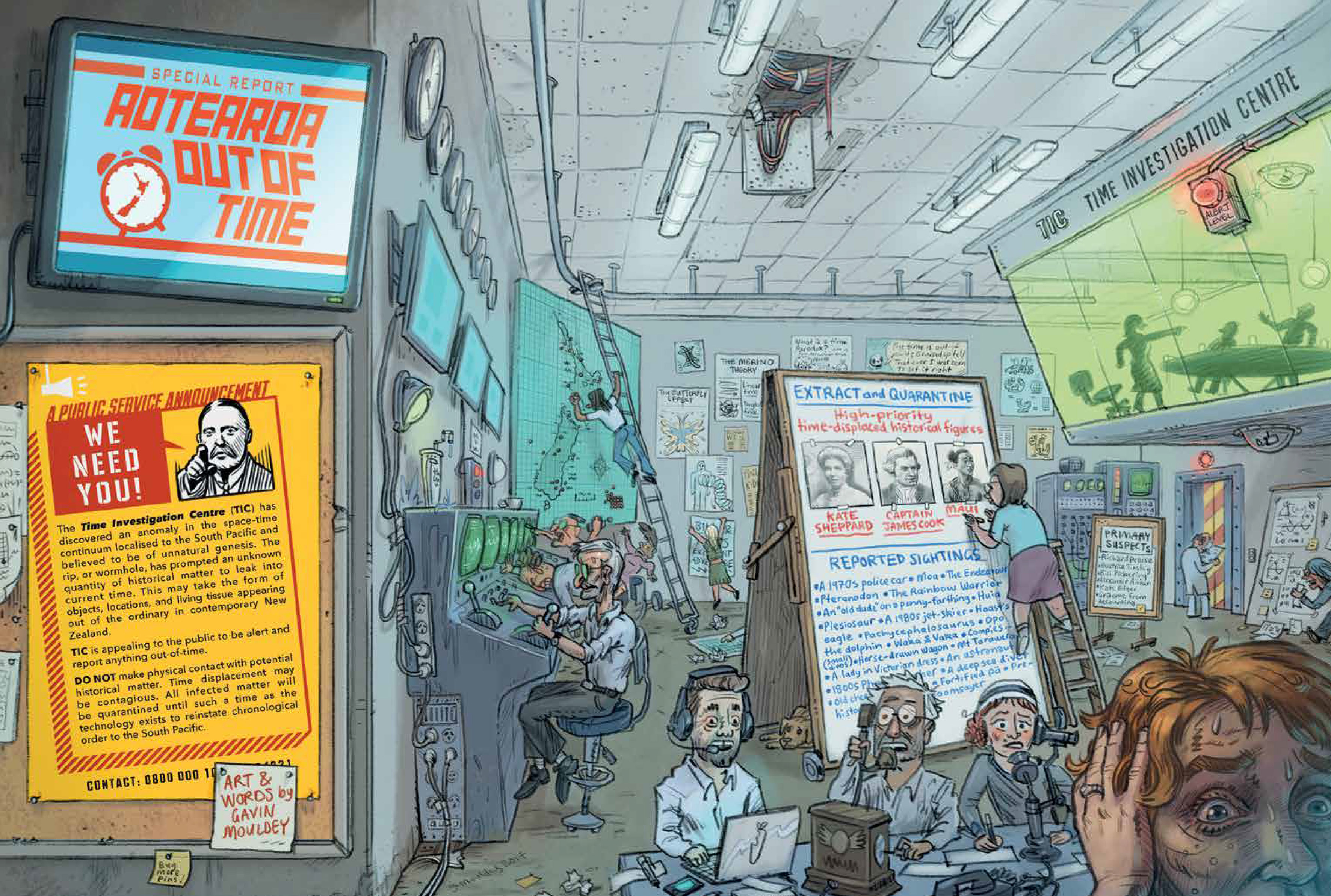

Tearaway Magazine was the first stop for aspiring Whanganui illustrators in the 1990s, so that’s where Gavin Mouldey started his doodling career. His commissions for the youth magazine were mostly drawn during class time at high school, along with a weekly cartoon for the local Chronicle called From The Tin Shed (Far Side inspired). Eventually the teachers and principal caught on, and started commissioning him to draw staff caricatures and illustrate text books.

Gavin continued to doodle through post graduate studies and in foreign lands, until eventually returning to New Zealand and building a family nest in the Kapiti coast. He has created artworks for greeting cards, TV cartoons, office walls, chapter books, close to 30 school journals, and now two Annuals. The Game Of Awesome, which features over 230 of his illustrations, has been winning national and international design awards and is available for free to all NZ schools. Gavin’s latest book, Toroa’s Journey written by Maria Gill, is available in October from Potton & Burton.

Gavin has created a piece of visual storytelling, ‘Aotearoa Out of Time’ for Annual 2 (an extract is above).

These are the books that formed his childhood:

Riverboat Adventures, by Lucy and Eric Kincaid

This book borrows from Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind In The Willows, but with shorter, stand-alone chapters making it perhaps more toddler-bed-time friendly. I still have the copy that mum read me many times over, and its significance for me is really due to her. Mum makes any old book sound like a classic, but Eric Kincaid’s paintings made an impact too.

Fantastic Mr Fox, by Roald Dahl and Quentin Blake

Another storyteller who inspired my lasting love of children’s literature was Mr Dewson at Durie Hill Primary School. Mr D was Roald Dahl as far as I was concerned. He could also draw, and his chalkboard doodles might be the earliest influence on me painting on walls today.

Asterix At The Olympic Games, by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo

Could be any Asterix & Obelix album, but I remember copying the body builder poses from this one. I lost hours staring at the details in the ancient cityscape and village life illustrations. There was always something I hadn’t seen before, which was something I was trying for in my spreads in Annual.

David Larsen wrote stories all through his childhood, and then stopped, for reasons he cannot now well remember. Abject terror of other people reading them may have been a factor. While home schooling his children, an activity which a neoliberal economist would describe as ‘being unemployed’, he made the discovery that he could make small amounts of money by reviewing large amounts of books. This and the home-schooling kept him happily occupied for most of the next twenty years.

At some point during this period he noticed that people were occasionally reading things he had written, and the world had not ended. Around the time his children were leaving home, a friend suggested that the world would probably also not end if he wrote some short fiction for the School Journal. He tried this. He has written several more stories since. It turns out it’s still fun. David has written a bunch of things about children’s fiction and children’s films. His favourite in both categories is this essay about the Harry Potter film series. The essay is in four parts, but it is still significantly shorter than several of the Harry Potter books.

His story ‘The New Late Works of Mozart’ is in Annual 2.

These are the books that formed his childhood:

The Magician’s Nephew, by CS Lewis

One of the first proper books I read on my own as a child. All the Narnia books were important to me, and they still are. You hear a lot about CS Lewis’s faults as a children’s writer – he buries Christian allegory just below the surface where most kids won’t initially notice it, his ideas about race and gender are antediluvian – and these are real problems.

I’ve found them useful problems to talk about with kids; but truthfully, in terms of my own reading pleasure, I just love the books too much to care. Lewis was who he was, a damaged, complex, brilliant man, and there’s so much beauty and deep thought and wonderful invention in his work.

This is the one he wrote almost last of the seven, though it often gets presented as the first in the series, being a prequel; it’s the Narnia origin story, set in the years of Lewis’s own childhood, and among other things it’s about a boy whose mother is dying. Lewis’s own mother died when he was young, which is only one of the reasons I generally end up crying if I read this.

A Wizard of Earthsea, by Ursula Le Guin

Ursula Le Guin is my indispensable writer, the only great writer I’ve loved at every stage of my reading life. The Earthsea books were everywhere when I was a kid; people in my class at school who didn’t really read much still knew about them. They’ve faded out of the popular consciousness somewhat – adult readers are usually aware of them, but only a minority of reading children seem to be. I find this at once strange (they’re so much a part of my mental landscape) and somewhat comprehensible.

They’re morally complex books, in some respects heroic but in others deeply not (I’m talking about the first three, written explicitly for children, rather than the entirely anti-heroic later three, written very much for adults). And when I think about it, I didn’t actually understand the ending of the first book until I was in my twenties. And yet as a child I’d read it over and over.

The scene where the young not-yet-wizard Ged first encounters the shadow beast, a hunched, indistinct shape in the corner of the darkened room where he’s been reading a book he should never have opened, became one of my primal childhood nightmares.

I am a big believer in childhood fears. The stories that scare us are often the most valuable ones.

Citizen of the Galaxy, by Robert A Heinlein

People who did not grow up as wild-eyed scourers of libraries for books with ‘SF’ on their spines mostly know Robert A Heinlein as the author of Stranger In A Strange Land. I didn’t even hear of that book until I was 14 or 15, but Heinlein was one of my favourite writers as a pre-teen.

Every year through the 1950s and into the early 60s, he published an adventure book for children, and I could talk to you at boring length about nearly every one of them. I eventually figured out that he writes out of a hardcore libertarian worldview that I find far more obnoxious than CS Lewis’s brand of Christianity, and there are other ways in which his stories seem very dated now. But even so, I expect a major Heinlein revival within my lifetime, because as a storyteller he’s hard to beat.

I read this one when I was ten, and I can still put myself in that thronged alien square on page one, where the old beggar is watching a slave auction. A young human boy is about to be sold off. Am I the boy, when I remember this, or am I the beggar? Heinlein writes it so well that in my memory, I’m both.

Annual 2 is reviewed in detail here.