Should children be exposed to books about slavery, racism and violence? Today Sisilia Eteuati, an Auckland writer, lawyer and mother, gives us her very good reasons for putting serious subject matter on her children’s bookshelves.

On the eve of my 39th birthday, I sat outside on a beautiful summer’s evening and watched I Am Not Your Negro.

Earlier I had asked my six-year-old who was engrossed in Lego if he wanted to come. A sprawling space city was emerging beneath his patient fingers. ‘It’s an important documentary,’ I told him. ‘Can I have popcorn?’ he asked. ‘Yes, but if you come you have to sit and watch the whole movie quietly. A lot of it might be in black and white.’ He shrugged. ‘I don’t really like black and white.’ He pressed another block into the transporter soon to take its place in the spacescape that had spread out across his bedroom floor.

And why, you may ask, was I asking a six-year-old to a film that shows lynching, slavery, extreme brutality and murder?

I am a Samoan mother to Samoan children. It’s my responsibility to be raising children who understand the world as it is, to understand not just our world’s history, and not just how we want it to be, but our world’s reality.

James Baldwin says:

‘Leaving aside the bloody catalog of oppression, what this does to [the American Negro] is it destroys his sense of reality. It comes as a great shock around the age of 6-7 that when Gary Cooper killing off the American Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, the Indians are you.’

I am not Black American. I am not dealing with the ongoing terrible brutal legacy of slavery. And still.

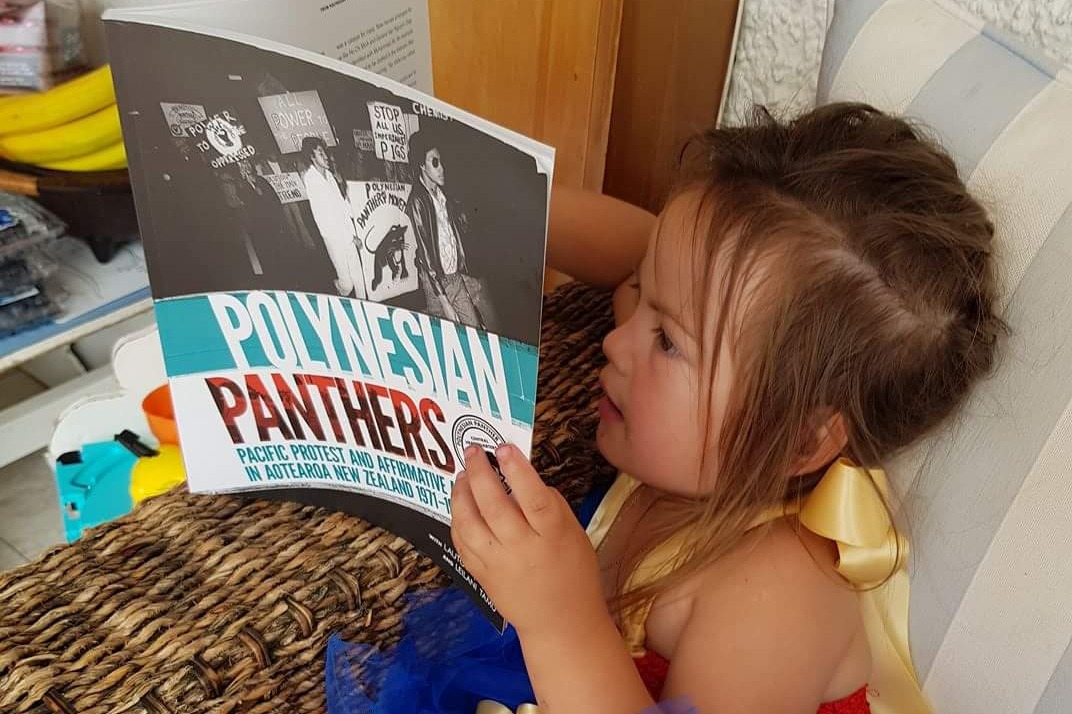

My children’s bookshelves do not and cannot just contain fairytales and flights of fancy. The books we read every night, snuggled up in our comfortably middle-class life in Aotearoa, can’t just be delightful stories about mice who outwit monsters. They can’t just be books with cunning rhymes and clever words like rapscallion that make my nerdy self deeply happy as they roll around my mouth. They can’t just be books on dinosaurs and books that give ratings to the deadliest creatures on the planet (even though there is a page rightly dedicated to humans). They can’t just be books by comedians that make my son laugh every time I am forced to repeat phrases like ‘booboo butt’.

The books we read every night, snuggled up in our comfortably middle-class life in Aotearoa, can’t just be delightful stories about mice who outwit monsters.

I can never forget that reading, even to children, especially to children, is a political act. Reading conveys powerful ideas, and ideas are important. They shape the entire world. They shape humans. Ideas make the difference between whether you see learning te reo as someone else’s problem (yes, Mike Hosking, I’m looking at you), or whether you recognise that each and every one of us in Aotearoa who is not Māori has benefitted from colonisation and dispossession and that we all have an ongoing duty to take as many real steps as we can, like learning te reo, to try and help address the ongoing effects of that colonisation and dispossession.

Ideas help you know that countries can’t be grouped and dismissed as ‘shitholes’ whose immigrants you definitely don’t want. Ideas stop you pretending that white supremacists who march with tiki torches are ‘very fine people’ who can be equated with those who march against such hate. Ideas make the difference between going down to the ballot box and voting and just throwing your hand up and saying ‘all parties are the same anyway’ and then complaining for another three years about the government.

I can never forget that reading, even to children, especially to children, is a political act.

We read because I can’t have my children go into the world not armed with ideas. I cannot have them not prepared for reality.

Ideas can prepare you for the day the school secretary butchers your and your brother’s Samoan names and carelessly jokes to the Principal ‘two more for the remedial classes, then,’ because your palagi mother and your fair skin meant they didn’t realise that name belongs to the children in front of them. Ideas can prepare you for the day someone in your Masters of Creative Writing class kindly tells you that it’s okay, they didn’t understand that term either and English is their first language, because your accent means they can’t imagine it’s yours too. Ideas can prepare you for your first day at work when your boss tells you to ‘watch out for those Aboriginals in the park’, and the day you come back from being yelled at by a judge to be comforted by colleagues who tell you it was inevitable, given that you were both a woman and not white.

Apparently, my children can’t be convinced to come and watch excellent documentaries in black and white just yet. But even if they did, I would not want them to have tears streaming down their face for most of the film, like I did watching I Am Not Your Negro. My tears were not just because of the terrible reality on the screen but also because I realised all over again that, despite being a child who grew up in Samoa drawing black power fists, despite being a teenager who studied this particular history while blasting Public Enemy and NWA on repeat, still. Still I am the product of a Western education. Still I am unlearning.

Still I am the product of a Western education. Still I am unlearning. And so we read.

And so we read.

We read Remember that November by Jennifer Beck where Aroha stands up at a school speech competition, a white feather in her hair, and tells the story of the invasion of Parihaka and her tūpuna who peacefully resisted in 1881. We read Stolen Girl by Trina Saffioti who re-imagines how it must have been like for her maternal grandmother was stolen from her family, a girl who is always trying to go home. We read Anh and Suzanne Do’s book The Little Refugee, which tells the story of a young Vietnamese boy whose family risk dangerous seas and pirates to escape to another country where he grows up to be a celebrated comedian and writer. We read The Forgotten Taniwha by Robyn Kahukiwa, about the taniwha Ngākau Pono who is forgotten with the coming of the Pākehā and then remembered. We read The Arrival by Shaun Tan and make up stories about the haunting images it contains.

We read Aunt Harriet’s Underground Railroad in the Sky by Faith Ringgold where children follow the road their great-great-great-grandparents’ escape from slavery led by Harriet Tubman, who escorted over 300 slaves to freedom. We read To Hell with Dying by Alice Walker about children who give meaning to an elderly neighbour’s life. We read Patricia Grace’s Haka so my children know what those powerful words mean and the people they belong to. We read Maraea and the Albatross where Maraea’s whānau’s relationship with albatross and her steadfastness in maintaining that relationship is rewarded. We read Meariki: The Quest for the Truth the graphic novel by Helen Pearse-Otene and Andrew Burdan about a brave slave girl who saves a princess and has an even greater destiny. We read The Sacred Hill by Gordon Hookey where four strong different kangaroos representing the more than 500 different indigenous peoples in Australia are living happily before myna birds invade and take it over. We read Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls by Eleni Favali and Francesca Cavallo about extraordinary women from all over the world who have led in many different ways.

We read and read and read.

My children, who are now almost seven and almost four, sometimes ask me tough questions about these books. Sometimes they complain when I won’t just read mind-numbingly boring Marvel origin stories or yet another Wiggles book and be done with it. Other times they have delighted me. I expected some questions from my then almost three-year-old as I read to him from We Are All Born Free: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Pictures. As an unmarried mother I was particularly nervous as I read to him about marriage: ‘Men and women have the same rights when they are married.’ I expected some reflection on the state of my relationship with his father.

‘What’s a woman?’ he asked.

‘Mummy’s a woman,’ I answered.

‘No, you’re a person!’ he corrected me.

This reminder from my small child has remained with me. I think of my child that beautiful summer’s evening, carefully pressing Lego blocks together, creating a world from tiny interconnecting pieces. The pieces that he has been given both allow him to build and limit him. Ideas can be like that too. I recognise that being able to access and read these books to my children, books that provide ideas for my children to carefully press together to shape something wonderful, is privilege and fortune.

I have always wanted to change the world. When I was younger I thought that might be through practising law, working internationally, being a writer, or doing any other number of wonderful and wild things. Now I understand I am changing the world, I am shaping my children’s ideas, I am showing them reality and how to cope with reality.

One book at a time.

Editors’ note: The Reckoning is a regular column where children’s literature experts air their thoughts, views and grievances. They’re not necessarily the views of the editors or our readers. We would love to hear your response to any of The Reckonings – join in the discussion over on Facebook.

Sisilia Eteuati

Sisilia is a writer and poet. She has a Masters of Creative Writing with Honours from the University of Auckland, where she was awarded the Sir James Wallace Master’s of Creative Writing Scholarship on the strength of her writing portfolio. She makes ends meet by practising law.