Babies don’t come with manuals, or book lists. Today journalist and broadcaster Guyon Espiner recounts how he and his daughter have discovered zen pandas and Roborovski hamsters along their bilingual reading journey.

My reading life with Nico began the day after she was born and would establish something of a pattern for my parenting: curious decisions based on limited information leading to surprising consequences.

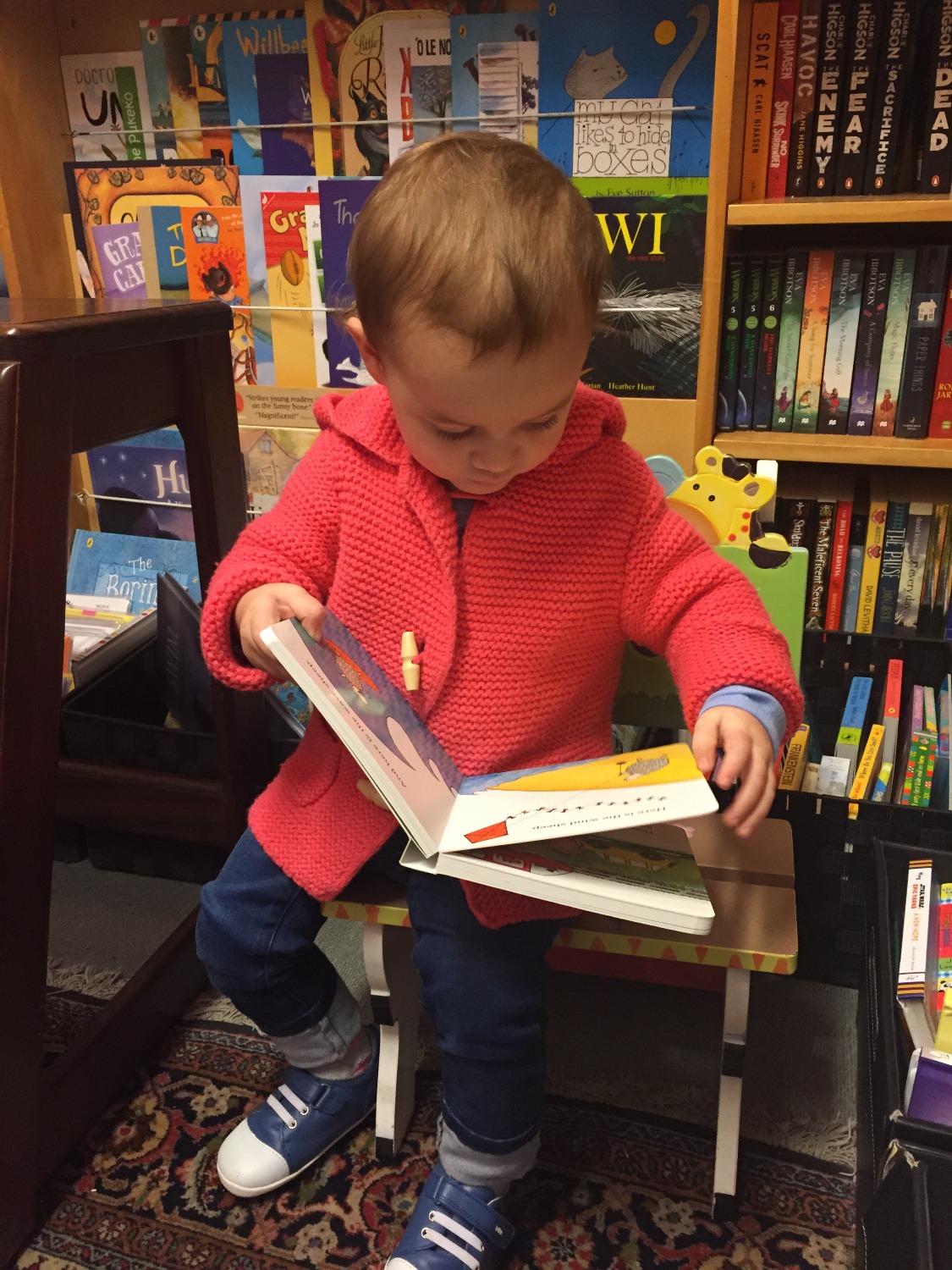

I knew so little about looking after this little matahīapo that I closely watched other parents in the hospital and scribbled down notes on how they were holding their babies. There was only one thing for it. I headed to the hospital book shop, or at least the corner in the shop devoted to reading rather than healing, although later I would learn the lines aren’t so cleanly drawn.

Given my love of skulking in a book shop my visit was indecently hasty – but then time changes when you have children. There is no mystery about this change in the nature of time. It’s quite simple. You don’t have any time.

. . . time changes when you have children. There is no mystery about this change in the nature of time. It’s quite simple. You don’t have any time.

The first of my choices was uncontroversial: The Noisy Book. Big picture of a firecracker on one page. The firecracker goes boom on the facing page. Big picture of a drum. Ratta-tat-tat. You get the picture, in fact it’s indelible after the 27th reading.

My second choice was controversial and was met with hoots of derision from my wife Emma – a noise snugly at home in the pages of my first choice. I had chosen a book called Pets. Now, as benign as this sounds, this small picture book – ‘Age 0-plus. Over 100 fun first words to learn!’ – is more accurately described as a technical manual, and not about the animals themselves but their peripheral worlds. There is a feature on bird seed, a section on Roborovski hamsters and close up photographs of horse cleaning equipment including a curry comb. There are some cat photos too, which are helpful if your newborn wants to acquaint herself with Maine Coon breeds.

And you can guess where this is going. Yes she liked The Noisy Book – in fact it’s all about noise in those first few months, which is why poetry and song are instant highs – but she absolutely loved Pets.

While I still couldn’t wind her, or settle her to sleep – or comfortably hold her without glancing at my notes – I had already learned some valuable lessons as I created my baby bibliography. Sound, absolutely. But also detail. Kids love it. Nico remains highly susceptible to seemingly tangential clusters of information. At about 2.4 she memorised the names of all the bounty hunter droids in Star Wars books and could spot IG88 in a page bursting with fiends and freedom fighters. Reading the magnificent Winnie the Witch books at night, much of the time was taken up with counting the critters crouching in the corners of castles.

I learned a few other things about kids and books along the way. Children can sense a good story like a successful Hollywood producer. The classics are classics for a reason. A Lion in the Meadow, the bloody Tiger who Came to Tea (our Tiger came to tea more than 800 times and never said thank you), Where the Wild Things Are – are just damn good stories.

Children can sense a good story like a successful Hollywood producer.

You do have to watch it though. Some of the oldies struggle to stand up in 2018. Nico, now 4.2, loves The Witch in the Cherry Tree but I struggle with David’s mother, who meekly bakes the cupcakes. And yes I know it’s faux naivety but getting schooled by a toddler in the ways of witches does grate a little. In Julia Donaldson’s ZOG, Princess Pearl has a nice riposte, rounding on the dragon:

‘Don’t rescue me! I won’t go back to being a princess

And prancing round the palace in a silly frilly dress…’

Reading to Nico in te reo Māori has been a big part of my language journey over the last year or so and it’s getting easier to find good stories, largely thanks to Huia Publishers. Kei Hea Tāku Pōtae? is a good one. An old man wants to go fishing – nā te mea e marino ana te moana, e whiti ana te rā – but he can’t find his hat. He spends the story asking his whānau where the bloody hell his hat is, to which most of them answer: Aua. Rapua, which roughly translates to, I dunno, look for it. In a case of art meets life I trudged around the house in the Auckland summer asking the exact same thing. Kei hea tāku pōtae? Nico didn’t look up. ‘Aua. Rapua!’

Timo te Kaihī Ika is another beautiful one from Huia, by Mokena Potae Reedy and Jim Byrt. Timo goes fishing with his dog and learns the hard way about why he should throw the first fish back into the ocean. The language is a little more advanced in this one and I did spend most of an afternoon scribbling translations in pencil over the pages. There are also te reo versions of classics such as Kei te Kīhini o te Pō (In the Night Kitchen), He Wāhi i te Puruma (Room on the Broom) and Te Mīhini Iti Kōwhai (The Little Yellow Digger). For a first step reo story, read Kei hea te Hipi Kākāriki and join the quest to find the green sheep who (spoiler alert), it turns out, is having a moe.

As well as wrestling with learning the reo in my mid-40s I also spend a bit of time interviewing politicians on the radio. I’ve found reading to a toddler quite helpful there too. Politicians and toddlers immediately gravitate to talking about something other than the narrative you want to pursue. Ask a poorly configured question and a politician will dart down the rat hole you opened up for them. Kids too. Confronted with a key in a story, Nico asked, what is this for? Well, what could you do with a key, I replied, guiding her towards the treasure chest on the facing page. Well, you could put a key on your head, she replied. Quite correct. Poor question. The trick is not to invite distraction.

Ask a poorly configured question and a politician will dart down the rat hole you opened up for them. Kids too. Confronted with a key in a story, Nico asked, what is this for?

I’ve recently been reading my daughter Zen Ghosts by Jon J Muth, a curious book my wife brought home from the Mt Roskill library. It takes me back to my point about detail and complexity. Kids can cope with it. This is a story about a panda who visits some kids at Halloween and takes them to another panda who tells them a story. But are there two pandas or only one? It’s based on a story by Master Wu-men Hui-hai, a Chinese Buddhist Monk who died in 1260. It explores the duality and questions of whether we have only one consistent identity or more. The author’s note (don’t read this to your children) asks ‘When our hearts are taken in two different directions, where are we?’ Regardless of the philosophy, trust me, your kid will love it as a yarn about whether there are two pandas or one. That is if you keep them on track. We came to a bit where two of the characters had to ‘face the consequences’. What are consequences, asked Miss 4.2. Well, if you had a bowl of yoghurt and you threw it at the window, I helpfully explained, then the consequence would be that I would be very angry with you. When did I have a yo-yo, she asked. Was I good at it? Who taught me? What happened to it? That was the end of the zen panda story for the night.

What are consequences, asked Miss 4.2. Well, if you had a bowl of yoghurt and you threw it at the window, I helpfully explained, then the consequence would be that I would be very angry with you.

Time is up on the Pets book too, of course. And thank goodness right? I’d never even heard of half the animals in this dreadful little book, with its conure parrots, akhal-teke horses and long-haired sheltie guinea pigs. It’s funny though. We had a big clean out after the summer holidays and got rid of a lot of useless, old things but it’s still here on the bookshelf. I must have forgotten to throw it out

Guyon Espiner

Guyon Espiner is the presenter of Morning Report on RNZ National. He has been a journalist for 20 years, working in both print and broadcast media, and has been political editor for Television New Zealand and, earlier, the Sunday Star Times. He has reported on trade from China, on war from Afghanistan, on politics from Washington, on international relations from Papua New Guinea and on climate change from Antarctica.