Disability consultant, activist and blogger Robyn Hunt explains the literacy challenges faced by children with disabilities, and the many different ways they are able to access books – as long as the resources, regulations, funding and technology allow.

The earliest independent reading I remember, apart from the painstakingly handwritten first readers, were the large print School Journals, which I was allowed to keep. I treasured them. I still recall some of the stories and the black-and-white line drawings. One was about a little elephant who never cried, except when soap got in his eyes. There was a picture of him in the bath, waving his trunk happily, with bubbles everywhere and puddles on the floor. (I was disappointed when the published history of the School Journal neglected to include mention of large print.)

My parents were initially worried about their severely visually impaired daughter damaging her fragile vision by reading as if her life depended on it. Fortunately most children’s books had large print. My passion for reading and books was encouraged by my grandmother who spent lots of time reading to me before I was able to read for myself.

In 2013, Statistics New Zealand found that 95,000 (11% percent) of children in New Zealand were disabled. The biggest group had learning disabilities: six percent of all children (49,400 children) had difficulty learning. A small group of children were blind or had low vision (about 1.6% of the population), or were deaf or had some hearing loss (2.25% of the population). A small number of children have more than one impairment.

For many disabled children, reading and books can provide an escape from social isolation and the limitations of the here and now. In a book you can be anyone you want and do things that are maybe impossible in real life. And everyone loves a good story!

Engaging books including disability or with disabled characters can also be helpful to a child’s growing sense of self and place in the world, as long as they aren’t boringly earnest, preachy and overtly educational – I resisted and resented being given ‘improving’ books about the ‘inspirational’ Helen Keller.

Engaging books including disability or with disabled characters can also be helpful to a child’s growing sense of self and place in the world …

Finding books you can read which reflect and explain your own life and experience might be affirming, but they are few and far between in bookshops and libraries for young children, although there are more for young adults. Good New Zealand stories including disability or disabled characters are almost non-existent. There are some children’s books in public libraries about specific impairments. These are probably more helpful for parents and teachers.

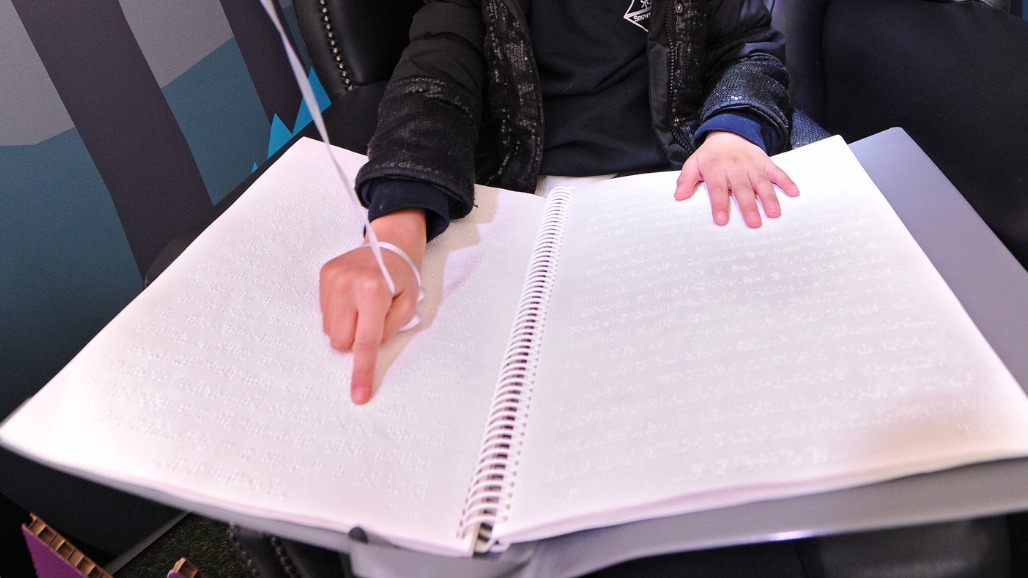

Access to the appropriate and accessible tools and good teaching for the development of literacy is necessary, along with access to accessible books. Deaf children who don’t have access to New Zealand Sign Language as their first language may have difficulty with learning to read and write English. Blind children need braille to develop literacy, while partially sighted children need large print. Learning-disabled children need particular interventions. There are specialist libraries, such as CCS Disability Action and IHC, and the Deaf education centres in Auckland and Christchurch, which provide support for families and teachers of children who are Deaf and disabled. The Blind Foundation library provides support for those who meet vision-loss membership criteria.

I found some good examples of books for young children in the CCS Disability Action library. A little board book, while not including disability specifically, did talk about the differences but essential similarities between all children and peoples: Whoever You Are by Mem Fox and illustrated by Leslie Staub (Red Wagon Books). Two picture books were also appealing: Sometimes by Rebecca Elliott (Lion) is a gentle, beautifully illustrated story about Toby and Clemmie who spends a lot of time in hospital, and how both children cope. I Have the Right to be a Child, pictures by Aurelia Fronty, translated by Helen Mixter (Groundwood Books, House of Anansi Press) is also beautifully illustrated. It describes the UN Children’s Convention for young children. I particularly like the no-fuss way it includes disability.

Some disabled children need information in alternative formats such as electronic, audio, braille, or large print versions of standard print educational materials (such as textbooks, novels and non-fiction, general reading, student guides, magazines and periodicals). Electronic versions include, but aren’t limited to, e-text, scanned text, and web-based text.

Less than 10% of print material is available to blind and vision-impaired and other print-disabled people in developed countries like New Zealand …

But some of these children have limited access to books in alternative formats. Less than 10% of print material is available to blind and vision-impaired and other print-disabled people in developed countries like New Zealand, according to the World Blind Union and Blind Foundation. For example, the last book in the Harry Potter series, Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows, first published in 2007, isn’t available in braille yet.

The Blind Foundation produces most of the children’s books in alternative formats in New Zealand. Fiction, non-fiction and educational resources are produced in one or more accessible formats. Production is limited because of the high cost and significant time for production, particularly of braille. The Foundation produces the School Journal in braille and large print for the Ministry of Education. There are difficulties, some technical – for example, producing macrons and other scripts in braille when producing children’s books in Māori, Pacific languages and other languages spoken by New Zealanders, such as Mandarin and Arabic. As well as technical problems, there are problems finding fluent narrators for audio production in languages other than English, although audio production is generally easier than braille production.

Digital options for accessible format production have made some difference to availability. An example is the New Zealand Sign Language Ready to Read books available on the Ministry of Education page on iTunes.

The Marrakesh Treaty, developed by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) and the World Blind Union (WBU), would make alternative-format production much easier. It directly addresses the thorny problems of copyright access. The treaty enables “authorised entities,” such as blind people’s organisations, service providers and libraries to more easily reproduce printed works into accessible formats, like braille and DAISY (Digital Accessible Information SYstem), for the production of talking books, large-print and e-books, for non-profit distribution. It will also allow authorised entities to share accessible books and other printed materials across borders with other authorised entities. This will help avoid expensive and unnecessarily duplicated reproduction of the same books in different countries. The Marrakesh Treaty came into force in 2016. Australia and Canada are among the 33 countries that have ratified it. New Zealand has indicated it will ratify the Treaty, which requires changes to the Copyright Act, and this will take time.

Technology has revolutionised access over the last ten years, as equipment has become less cumbersome, expensive and specialised. Regular, accessible, ‘out of the box’ and relatively affordable devices such as iPads and smartphones run sound and large print. PCs and other devices support refreshable braille displays, screen reader software and the relatively easy captioning of videos, Sign Language videos and read aloud software for dyslexic children. The 21st century web is a powerful access tool for children and young people when used well; for example, talking books can now be accessed and downloaded on mainstream devices such as iPhones and iPads, as well as specialist equipment, and children with dyslexia can use software that reads aloud and highlights text on the web. Disabled children need access to these tools, too.

The provisions for access in the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) lend focus and urgency to the issue. New Zealand ratified this treaty in 2008. Deaf and Disabled children have the right to be literate, and to read and achieve alongside their non-disabled peers.

Deaf and Disabled children have the right to be literate, and to read and achieve alongside their non-disabled peers.

I hope that no family in New Zealand ever has to transcribe and hand-make early readers in large print as my family did. I still remember the foolscap-size folder tied with black shoelaces, with the text written in thick black beauty pencil, and the pictures cut out and stuck in above. Without them, and a supportive and patient new entrant teacher, I may never have learned to read well, pursue a university education and follow a career in words.

Robyn Hunt

Robyn Hunt is a disability consultant, activist, blogger, and commentator. She is a founder of the Crip the Litproject and a former human rights commissioner.