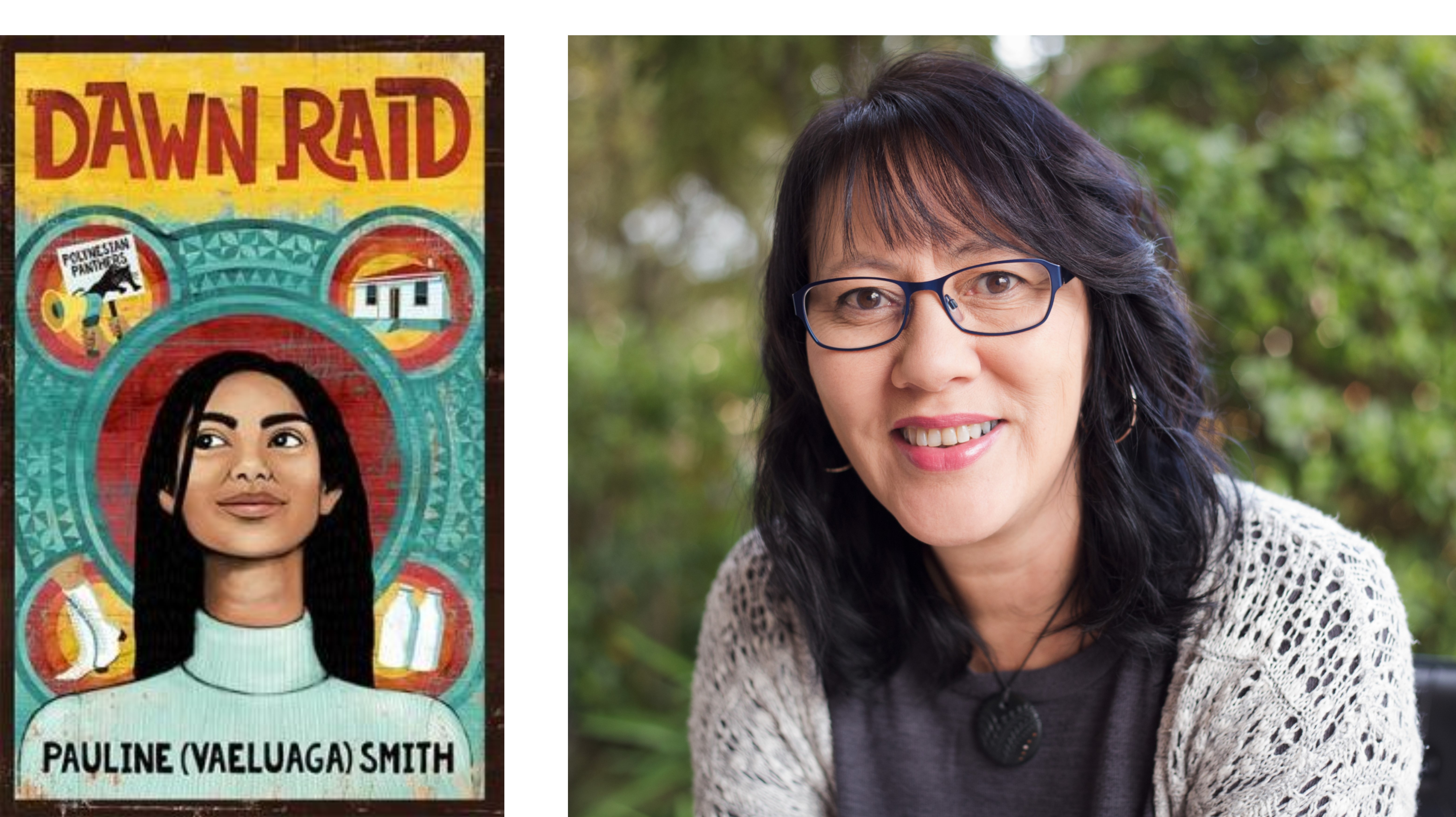

NZ-Pasifika writer Pauline (Vaeluaga) Smith has recently published her first book, Dawn Raid, as a part of Scholastic’s ‘My New Zealand Story’ series. Leilani Tamu catches up with Pauline to find out more about her writing journey and the experience of writing a book for young people anchored in the concept of ‘educate to liberate’.

Dawn Raid is a great read that captures an important time in New Zealand’s history, especially for Pasifika peoples. What made you decide to write it and who do you see as the key audience?

My work as a lecturer at the University of Otago, College of Education alerted me to the fact that many of the students had little or no knowledge of the Dawn Raids, or of the Polynesian Panther Party’s role in addressing this injustice. I wanted to create a book that would help people of all ages to be informed and understand about this important part of New Zealand history. I have always been a keen reader of the Scholastic ‘My New Zealand Story’ series. They make history very accessible to young people. They are told through the eyes of a teenager writing a diary, so people of all ages can learn about historical events.

How would you describe the main character in the book, Sofia? What aspects of Sofia’s character, if any, are based on your own personality?

Sofia is the 13-year-old girl that I would like to have been. Sadly, I was politically and socially unaware until I went to University in my late-twenties. It was there that I learnt about the Treaty of Waitangi injustices, Bastion Point, protesters and activists. I was enlightened. I guess I admire Sofia because she was enlightened at such an early age. The likeness between Sofia and myself: we both have a very strong sense of justice, we love learning about culture, we love a good laugh, and we are goal-focussed and responsible (well, most of the time).

Sofia is the 13-year-old girl that I would like to have been.

In what ways, if any, did your own personal history and upbringing as a Pasifika New Zealander shape your decision to write the book, and the writing process?

My heritage is Samoan, Tuvaluan on my Dad’s side and Scottish, Irish on my Mum’s. Having a foot in the Palagi and Island worlds was a real asset to writing Dawn Raid. Many of my childhood experiences formed the backdrop for events in the story. I learnt from a friend, Victor Rodger, that your personal experiences make great material for writing. It makes perfect sense because, if you think about it, who knows your experiences better than you!

I think my Pasifika heritage was evident throughout the interview phase creating Dawn Raid, as I know how important it is to be respectful of other people and their stories and experiences. I spent a lot of wonderful hours meeting and interviewing members of the Polynesian Panther Party. There was always food, connections with others, time to talk about nothing and time to focus. All of these are important Pasifika values of building and nurturing relationships and showing respect towards each other.

I spent a lot of wonderful hours meeting and interviewing members of the Polynesian Panther Party.

I was fascinated by the journey that Sofia’s parents go on during the book, in particular the complex emotions and challenges that her dad has to grapple with. Can you tell me more about these inter-generational tensions in the book and a bit more about Sofia’s dad?

Sofia’s dad (like my own father) immigrated to Aotearoa for a better life. To help them fit in, many Pacific Island people took on or were given English names. This was often to make it easier for Palagi/European New Zealanders to say their names and at times helped them fit in better. I have to admit to being surprised when I realised my own father’s name wasn’t Fred or Freddie, but was actually Fou-Liki.

I have to admit to being surprised when I realised my own father’s name wasn’t Fred or Freddie, but was actually Fou-Liki.

In terms of the inter-generational tensions, I was very moved by a story Tigilau Ness told me. He said, ‘My mother would always say, “Why you make trouble with the police?”‘. He said his parents’ generation wanted to work hard, fit in and not make any trouble. This made it hard for them to understand why their children were challenging police, protesting, being arrested and being put in jail. Tigilau said when Nelson Mandela came to New Zealand, he thanked those people who protested against apartheid in South Africa. Tigilau got to hongi with Nelson Mandela and that was the moment when his mum realised what the struggle had been for, and that it was worth it.

I loved that the book wove in real characters who are recognised NZ-Pasifika people like Tigilau Ness and his (then) baby Che Fu. Can you tell me more about this generation of Pasifika social-change makers and what your research revealed about them? Were there any surprises along the way?

Tigilau Ness made sacrifices for his beliefs that only brave people can commit to. His decades of protests have taken many forms, from being on the front-line of protest marches to turning the tables on cabinet ministers during the Dawn Raid era. His music has carried strong social and political messages. Music is a talent that has been passed on to his son Che Fu and some of his grandchildren who perform with him now.

In Dawn Raid, Sophia’s older brother Lenny plays a critical role in connecting the family to the Polynesian Panthers. I was particularly fascinated by the relationship between Lenny and his friend Rawiri and the insights that this provided in relation to the important relationships between Māori and Pasifika social change-makers during this period. Can you tell me more about this?

The Polynesian Panther documentary informed my perspective for this part of the book. The producer Nevak Ilolahia (now Rogers) showcases a relationship between her Uncle Will Ilolahia and Ngā Tamatoa member Hone Harawira. In an interview about protesting and activism, Will and Hone describe an instant connection based on a shared understanding of the causes they were supporting. In other interviews, young Polynesian Panther members discuss how they convinced their parents to support causes like Takaparawha Bastion Point and to send food up to the point. What I took from this was, despite people’s ethnicity, there can be unity and solidarity in the face of oppression and injustice.

[D]espite people’s ethnicity, there can be unity and solidarity in the face of oppression and injustice.

How have young people responded to the book?

One of the best things that happened was when my grandson Brooklyn, who is nine-years-old, read the book and learnt about Martin Luther King Jnr. This made him choose Martin Luther King Jnr for his class project and he is now researching and teaching other kids and his family about him. I was proud and tearful when I heard this.

I have had the privilege of doing drama workshops with groups of young people based on exploring the Dawn Raids. After they do these, we get them to create placards with their thoughts and responses. I have been moved by the level of intensity, empathy and feeling they are able show about the Dawn Raids. It gives me confidence that the message of ‘educate to liberate’ is a powerful tool.

Leilani Tamu

Leilani Tamu

Leilani Tamu is a poet, public policy professional and former New Zealand diplomat. Her first book of poetry, The Art of Excavation(Anahera Press, 2014), was longlisted in the 2015 Ockham NZ Book Awards.