By Des Hunt

1918: Broken Poppies is the fifth and final book in Scholastic NZ’s ‘Kiwis at War’ series, which commemorates New Zealand’s involvement in the First World War. Author Des Hunt based this book on the experiences of two of his uncles who fought in WWI.

Struggling to survive in the trenches, close to enemy lines, amid the terror of gunfire and the whine of warplanes, Kiwi soldier Henry Hunt rescues a shaken little dog. Henry finds the dog is not only a comfort to his fellow soldiers on the battlefields of France, but a great ratter, too. Together, can they survive the Great War?

Chapter Six: Front-Line Duties

French/Belgian border

August 1917

Twelfth Platoon had no work detail that night. Instead they were listed for one early the next morning. For some reason, their work in the trenches had to be done in daylight. There was much grumbling about this as it meant they would be exposed to greater danger.

When it came time to leave, they found there’d been a change in the organisation of 12th Platoon. The normal sergeant had been sent to the field hospital with dysentery. His replacement was Sergeant Bell.

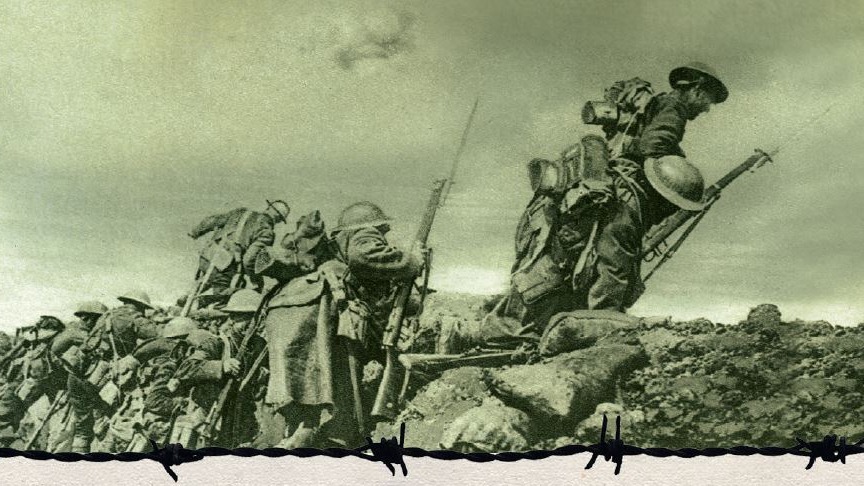

The march to the front line was in half darkness, which allowed them to reach the cover of the trench system before full daylight came. Instructions were given while they crouched in the reserve line.

The previous day, the fire trench at the extreme front had been attacked by mortar bombs lobbed from the German lines on the other side of the Lys Canal. The trench walls had already been repaired, but not the duckboards– the slatted wooden walkways that sat in the bottom of a trench. Fixing them was 12th Platoon’s job for the day.

A faint glow had formed on the eastern horizon when they made their way forward through the connecting trenches, passing two further lines before reaching their destination. Despite the damage, soldiers were already stationed along the fire-step, rifles poking through loopholes between the sandbags. Others were studying the enemy through periscopes. Every now and then shooting would break out from both sides, mostly due to boredom.

The duckboards had been reduced to rafts of kindling floating in groundwater. Repair seemed unlikely, and yet that is what 12th Platoon had to do. It would have been an impossible task at night; splinters of wood and exposed nails made the job dangerous enough by day.

Standing in the bottom of the trench, there was nothing to see of the outside world except for a patch of sky.

Standing in the bottom of the trench, there was nothing to see of the outside world except for a patch of sky. This would have been tolerable, if it weren’t for the stink: dead bodies, chloride of lime, and cordite from bullets and shells. The temptation to climb the walls to escape was strong.

Come midmorning, the troops manning the trench joined the workers for a welcome tea break. Henry took the opportunity to ask about the surrounding land. “What can you see through those periscopes?”

“A lot of barbed wire, ruins, crump-holes. Total chaos.”

“Crump-holes?”

“Bomb craters.” The soldier picked up a periscope.“Here, have a dekko. Just don’t stick it up too high.”

This was what Henry had been angling for. Getting the two mirrors lined up and facing in the right direction took some time, so it was a minute or two before Henry got a clear view. When he did, he gripped the periscope in shock. This was worse than anything he’d seen alongside the road at Plug Street. The ground between the trench and the canal was pockmarked with huge craters, some many metres wide. Surrounding these, and covering everything else, was barbed wire. This scene was repeated on the other side of the canal, in front of the German trenches. The canal itself looked out of place, its waters blue in a landscape of grey.

To the left was a ruined building with pipes and vats spilling out of an upper floor.

“The sugar factory,” whispered Henry. Which meant that the ground this side of it was where George was killed. Where his remains still lay.

Ed Bassett had called it a field. This was no field. Fields had grass and sheep or cows. In a field you could be at peace with the world. No one could ever be at peace in that place, not even the dead.

This was no field. Fields had grass and sheep or cows. In a field you could be at peace with the world. No one could ever be at peace in that place, not even the dead.

As Henry viewed the scene, his eyes blurred with tears. Within seconds he was weeping uncontrollably. The emotions he’d held back for almost a day welled to the surface, twisting his features in anguish.

He dropped the periscope, tumbled from the fire-step,and then staggered along the trench away from the group.

“Where are you going, Hunt?” yelled Sergeant Bell.

“He’s going for a pee,” said Jock.

“A nervous one, I bet,” sneered Bell.

Henry continued, lurching from the fire bay into the traverse that formed the zig-zag to the next fire bay. In there was as private a place as you could get in a trench. He leant against the wall, taking in huge gulps of breath, the tears still streaming from his face. Minutes passed before a voice broke into his grief. It was Sergeant Bell.

“Hunt! Get back here. Now!”

“Coming, Sergeant,” he replied, in almost a normal voice. And yet he knew that returning with wet face and red-brimmed eyes would lead to more abuse. He began marching back and forth in the traverse, composing himself.

“Hunt!”

“Yes, Sergeant!”

Wiping his eyes one last time, he shook his head and began heading back to the others. As he was about to turn into the fire bay, his left foot slipped off the duckboard and down into deep mud at the side. A sharp object pierced the sole of his boot, and from there drove into his foot causing an eruption of pain. He managed to stifle the scream before it got to his throat. But when he tried to lift his foot, a second spasm was so intense that no amount of willpower could keep him quiet. What’s more, his foot would not move.

A sharp object pierced the sole of his boot, and from there drove into his foot causing an eruption of pain.

Jock was first on the scene, with Tom close behind.

“What’s the problem, laddie?”

“Something’s stuck in my foot and I can’t pull it out.”

“Have a dig down, Jock,” said Tom. “Probably a nail.”

Dropping to his knees, Jock began digging in the mud. “It’s a huge nail,” he said. “It’s gone all the way through.”

He dug some more. “It’s sticking up from a board. Give us a hand. We’ll have to bring that out as well.”

Together they managed to lift the board and Henry’s foot out of the mud, but not without more intense pain. The reason was obvious: a rusty spike stuck out through the laces of the boot, just behind the toes.

“Should we try to pull it out?” asked Tom.

Before Jock could answer, another voice broke in.

“No! Leave it there. I want others to see this.” Sergeant Bell had arrived.

Jock looked up at him. “You think he’s done this intentionally?”

“’Course he has. He’s a coward. He thinks a self-inflicted wound will get him out of this war.”

“He’s a coward. He thinks a self-inflicted wound will get him out of this war.”

“That’s not fair, Sergeant,” said Tom. “That thing was buried in the mud. He couldn’t have known it was there.”

“Wrong, Private Lyons. He put his foot on it and then buried it in the mud. Cowards are cunning like that. He’s after a Blighty One. But he’ll not get it. More likely he’ll get a firing squad instead.”

* * *

It was night by the time Henry arrived at No. 3 Field Ambulance. This was no vehicle but a collection of Nissen huts and tents a few kilometres from his camp. By then the spike had been removed from his foot at a dressing station; the wound washed with disinfectant,and bandaged. A tablet of morphine had ensured there was little pain.

Now he lay on a stretcher amongst other injured waiting for an MO – medical officer – to assess the damage. Some of the soldiers were groaning, others unconscious or sleeping. The one alongside Henry was conscious and wanted to talk.

“You got a Blighty One?” he asked.

“That’s what they’re calling it,” said Henry. “What’s that?”

“An injury that will take you back to England. Then home, hopefully.”

“I got a spike through my foot. I doubt it will keep me out for long.”

“Might turn septic. You’d go back if you lost your foot.”

“I don’t want that. What about you? You got a Blighty One?”

“Don’t know yet. Threw a Mills bomb, but it exploded too close and I got shrapnel in my stomach.”

“Would they call that self-inflicted?”

“Better not! I was throwing the thing at a machine-gunpost.”

“A sergeant has reported mine as self-inflicted even though it was an accident.”

“Oh, that’s not good. That’s a capital offence. They shoot people for that.”

“Yeah,” said Henry, quietly. “So I’ve heard.”

The MO got to him over an hour later. “Let’s take a look,” he said, unwinding the bandage, “see what damage you’ve done.”

When the foot was exposed he squeezed and poked at it for a time. “You do this intentionally?”

“No, sir! My foot slipped off a duckboard into some mud.”

“Well, whether that’s true or not, this wound is not going the get you out of the war. They’ve done a good job of cleaning it. You just won’t be able to walk for a week or two. We’ll keep you here until the system sorts out what’s going to happen to you.” He moved on.

“We’ll keep you here until the system sorts out what’s going to happen to you.”

‘The system’ came in the form of an officer who introduced himself as Major Rose.

“Private Hunt, I’m here to check on a few things,” he said, waving a piece of paper. “This report from Sergeant Bell says that you left your post, moved to another part of the trench and intentionally stood on a nail sticking out of a board. You then buried the board in mud and screamed for help. Is that true?”

“No, sir!”

“Then you tell me what you say happened.”

He did.

“Mmm,” said Rose when he’d finished. “That’s more in line with another report I have.” He waved a second piece of paper. “This is written by a Lieutenant Charles Saunders, the OC of your platoon. He interviewed two other soldiers …” He looked at the paper. “… Privates McKenzie and Lyons, who told a similar story. He also found a Private Bassett from Second Wellington who reported informing you of your cousin’s death. From these investigations, Lieutenant Saunders comes to the conclusion that the wound is not self-inflicted, but an accident caused by distress and distraction.”

Henry waited, knowing that the major would now reveal which he believed.

“SIWs are serious business. But based on what you’ve just told me, I have decided to go with Lieutenant Saunders’ report and not Sergeant Bell’s. As a consequence, your record will show that you sustained an accident in the performance of your duties. No further action will be taken.”

After he’d left, Henry lay, processing the interview, particularly the efforts of his lieutenant. They were a surprise, since Charlie Saunders and Henry had never spoken. In fact, to the lieutenant, Private Hunt would just be a name on paper. And yet he’d gone out of his way to contradict the sergeant. Was there conflict between him and Bell? Maybe. The one thing that was certain though was that Bell would not be happy when he learnt of the decision. He was sure to take it out on someone, and it didn’t take a genius to work out who that might be.

Reproduced from 1918: Broken Poppies (Kiwis at War) by Des Hunt, published by Scholastic NZ 2018