For World Refugee Day, former refugee Nida Fiazi writes about her life and how books have intersected with it, and includes her recommendations for books (and attitudes) to help all people in Aotearoa understand the lives of refugees better.

Books and reading were never part of my life prior to arriving to New Zealand.

My mother had never attended school so unfortunately, at the time, she wasn’t literate either. However, this is not to say I was deprived of the wonderful gift of storytelling. My mother and I used to sleep together every night, whether that be in a boat, in a refugee detention centre, a resettlement centre or a home, until my little brother came along. Whenever I felt anxious, scared or restless she would narrate old Afghan folktales to me until I fell asleep, and boy, was she good at it.

I only realised how incredibly talented my mother was at this in my first year of university. I took a Children’s Literature paper where I discovered that most people learn how to narrate well (for example, using voices, the change in intonation, pauses) from being read to as a child. My mother had none of these experiences, yet she had such a knack for storytelling.

My favourite story she’d narrate was a Hazaragi folktale called Buz e Chini about a cunning wolf who attempts to eat the children of the goat Buz e Chini.

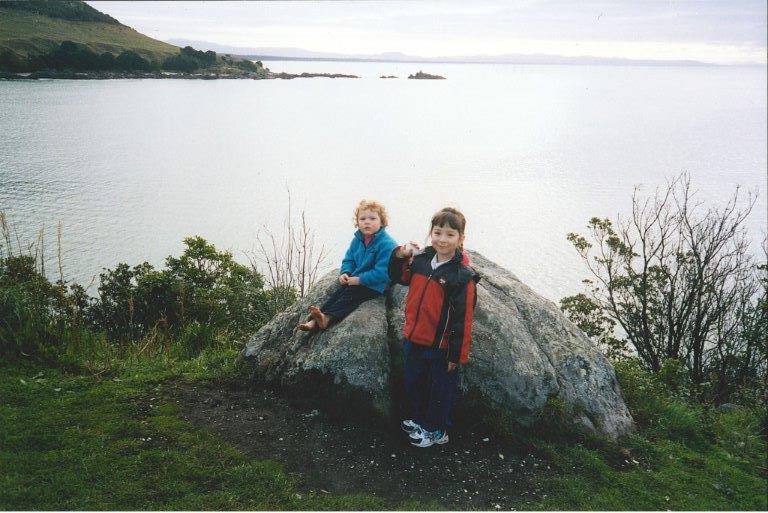

I was four years old when I first arrived in New Zealand. The refugee resettlement centre in Māngere was where I first encountered books, but because I did not know how to speak or read English it didn’t mean much to me at the time. I do remember being really passionate about learning the English alphabet.

The resettlement centre was where I had my first experience of education and I loved it. I loved to line up the cards with the letters of the alphabet in order and recite them as I did so. I remember The Rainbow Fish by Marcus Pfister and The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle. I remember carrying The Rainbow Fish everywhere with me. I don’t think I could even read it at the time but I loved to look at the pictures and marvelled at the foiled scales of the fish. When I look back on this I find myself just in awe of books all over again.

Despite my journey, my background and my differences, I grew up with the same classic books that Kiwi kids grew up with. Books provided a common ground for us.

I am from Afghanistan. I know that the first word that many people associate with my motherland is war. However Afghanistan is more than that. It’s a country rich with tradition and culture. It boasts the most amazing cuisine (I may be a tad biased but I doubt you’d disagree if you tried it), fashion and of course, most importantly, people.

My mother was in her late teens and I was just a toddler when she decided that staying in Afghanistan was not an option for us as we were surrounded by war and suffering. I don’t know the exact details because I was so young when we left and my mother does not like to relive her experiences because they are very triggering for her. What I do know is that somehow, she managed to get a hold of plane tickets to Malaysia where we and 15 other people were smuggled in a flimsy fishing boat to Indonesia.

Then from Indonesia my mother and I climbed aboard a small ship which we stayed on for 10 days before the Australian coastal patrol intervened. My mother and I, alongside the other passengers, were evacuated and placed on two more ships for a total of 30 more days and nights.

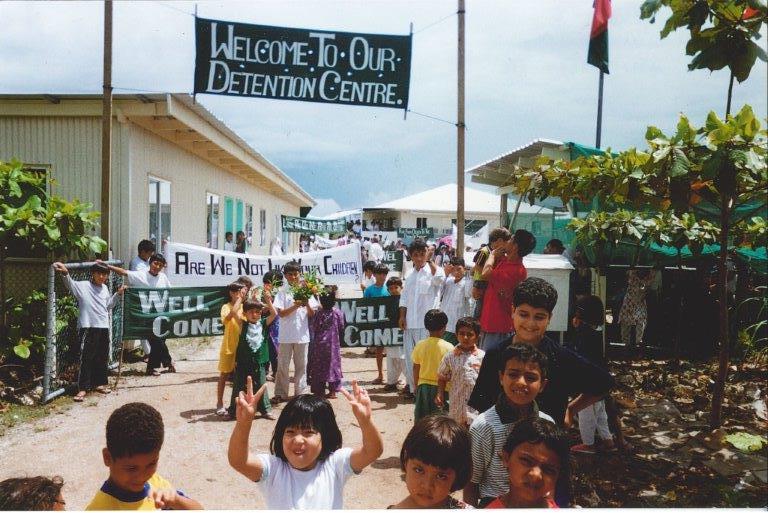

Our final destination after being at sea for so long was a detention centre on a remote island in the Pacific region called Nauru. I spent some of the most crucial years of my life at this detention centre.

They say the first five years of a child’s life are the most critical in terms of their development. It’s when the foundations of learning, behaviour and health are laid down. I was two when I arrived at the detention centre.

There I was surrounded with people, just like you and I, who were in a constant state of distress and suffering from ill health. At the detention centre, people were diagnosed with depression and anxiety everyday, but there were no proper doctors to help them cope. Some went to the extremes of sewing their lips shut in protest and even committing suicide upon learning that after everything they went through to get this far, they would be deported back to where they came from.

After two-and-a-half years in the detention centre, our case got approved and New Zealand offered us asylum.

I was two when I arrived at the detention centre.

I speak Dari, English and am in the process of learning Korean. My first language is Dari but unfortunately it is not the language I am most fluent in. I know how to read Dari, can hold basic conversations with people in Dari and I can follow along more complicated discussions but I cannot engage in these discussions myself. The only language I can do this in is English and as such I mainly read books in English.

Before I got my first public library card, my main source of books was the library in my primary school. I loved to read anything and everything I could get my hands on, whether that be the Famous Five books by Enid Blyton, the Geronimo Stilton series by Elisabetta Dami, Goosebumps by RL Stine or random books on astronomy and Greek gods. You name it, I was reading it all.

I absolutely adored anything by Jacqueline Wilson. I would read the physical copies of her books and listen to their audio versions on my DVD player as a child. Every single visit to the public library consisted of me checking their database for new Jacqueline Wilson books. I can confidently say that her books played a massive role in expanding my vocabulary as a child. She’s probably why I was so good at spelling too.

In my primary school, children weren’t permitted to issue books over the holidays because they would often forget to return them. I had been attending primary school long enough at this point to have developed good reading skills and my teachers had a good understanding of what kind of person I was. The two week break between the school terms was an awfully long time for me to go without having access to new reading material. I couldn’t bear to go that long without a book, so much so that I remember begging my teacher to let me issue books out over the holidays so I could satiate my thirst for stories and words. Much to my surprise, she eventually gave in and let me break the rules and I made sure to return the book when school started again.

The two books that impacted me greatly as an older child were The Glory Garage by Nadia Jamal and Taghred Chandab and Khaled Hosseini’s A Thousand Splendid Suns. I encountered these books at a time where I was really struggling with my identity as an Afghan Muslim growing up in New Zealand.

The Glory Garage detailed the many issues that Lebanese Muslim youth faced growing up in Australia and I remember feeling for the first time in my entire life that I wasn’t alone in the issues that I struggled with. A Thousand Splendid Suns was an unexpected gem. I went into it not really expecting much and came out of it a changed person. For the first time in my life I was being represented in literature. I felt validated. No one can put a price on that.

For the first time in my life I was being represented in literature.

I love reminiscing about my first trip to the public library after being issued a library card. I was a fast reader as a kid but my primary school would only allow you to issue two books at any one time. The public library on the other hand had a maximum of twenty books you could issue at once. You bet I took advantage of that. I came home after my first trip to the public library with twenty chapter books and I devoured all of them within that very week.

Over time, as my mum started attending English classes and improving her literacy skills, I would go to the children’s section, books that I had outgrown myself, and picked her some stories to read every week. It was our little tradition.

My current goal in life is to learn how to write professionally so one day I can write stories that help other people to heal. I have always wanted to write and publish my mother’s story. I want to recognise all the struggles she has had to face and still faces to provide me with a better future. However because her experiences are very triggering, this is proving to be a lot more challenging than I had anticipated.

After taking the Children’s Literature paper in my first year of university I realised how much I would have loved to read about people like myself as a kid. Representation matters so much – especially the representation of minority groups. It is so important to feel validated and that you belong. It’s now my goal to write children’s stories with diverse characters. I want to write about refugees, about Afghans and about Muslims. In doing so, I hope that other refugees and people in general find solace in these stories.

In order to achieve these goals I am attending university. I am currently in my second year of studying at the University of Waikato. I’m working towards a Bachelor of Arts degree majoring in Writing Studies with a minor in Anthropology. I have already learnt so much through experimenting with different writing assignments and reading material that I would not have personally picked out myself.

I think the most important thing to remember when it comes to the global refugee crisis is that refugees are people just like you. They had homes, jobs, friends and family that they did not want to leave behind. If refugees had the choice, many of them would not leave their homes but unfortunately they do not have that choice. They are forced to become refugees for many reasons, some of which include being displaced as a result of natural disaster, fleeing from war, genocide, from persecution for their ethnicity, religious beliefs, political beliefs and so on.

…refugees are people just like you. They had homes, jobs, friends and family that they did not want to leave behind.

Three years ago, my high school history teacher/social sciences teacher approached me about discussing my journey to New Zealand with her year 10 students. I agreed, not really thinking much of it at the time. I attended one of their classes where I told them my story and answered any questions they had for me. A few days later I encountered my history teacher again and she thanked me for coming to speak to her class and discussed how she had been struggling to help her students grasp the global refugee crisis and empathise with the refugees.

My teacher told me that the majority of the information and commentary her students had been receiving about the global refugee crisis was from their parents. They had not done any research on their own and unfortunately were not very sympathetic towards refugees. Many of them repeated the concerns of their parents and older family members who were worried about how the global refugee crisis would affect the current economic state of New Zealand and that the refugees would take job opportunities away from Kiwis, and bring backwards traditions to New Zealand. Their encounter with an actual refugee pushed them to reevaluate their former viewpoint and pushed them to do their own research and form their own opinions about the global refugee crisis.

I think that is the least we can ask from New Zealanders. If after reevaluating, they are still not for helping the global refugee crisis, at least it’s an opinion they formed on their own. Ignorance only breeds more ignorance.

In terms of the place of former refugees in Aotearoa now, I can only really speak about my own community as it is the one I know best. My best friends and I were amongst the first few Afghan refugees to settle in New Zealand in the early 2000s. Since our arrival, the Afghan community in New Zealand has grown immensely.

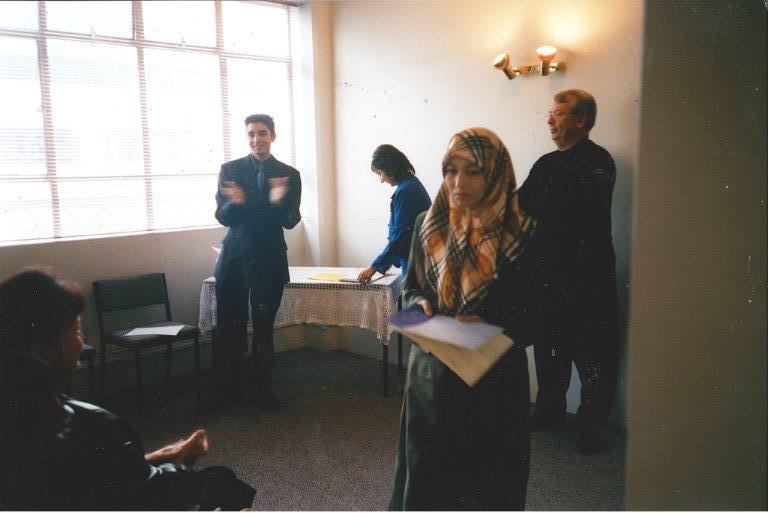

It’s incredibly difficult adjusting to new surroundings, language, food, social practices and laws regardless of your age. Many of those who were old enough to remember their journey were traumatised by it. My mother was one of those. But despite this, she and many others all made the effort to integrate within their new communities.

They attended language classes, made friends with Kiwis, learnt how to drive, use ATM machines, eftpos cards, how to catch a bus and all the things that those who grow up in New Zealand usually don’t have to think too hard about. Their children joined their schools’ football, hockey and cricket teams. They graduated from high school and are now attending university. Parents and children alike have jobs, are contributing to the economy and striving hard to make a living just like every other Kiwi.

Generations of Afghans have now been born Kiwis. New Zealand is their home, just like it is yours.

Nida recommends these books on the refugee experience

In The Sea There Are Crocodiles by Fabio Geda (Penguin Random House)

In The Sea There Are Crocodiles tells the true story of Enaiatollah Akbari, a ten year old Afghan boy, and his journey from Afghanistan to Italy. This is a great book if you are looking to understand the refugee experience through the eyes of a child but not in the form of a children’s book.

A Long Way Gone by Ishmael Beah (Sarah Crichton)

This memoir details the experiences of Ishmael Beah as a refugee who is forced to enlist as as a child soldier in Sierra Leone at the age of thirteen. At 16, Beah is rescued by UNICEF workers and sent to a rehabilitation center for boy soldiers where he is granted the opportunity to rebuild his life and regain his lost humanity.

In Order to Live by Yeonmi Park (Penguin Random House)

This autobiography details the struggles of Yeonmi Park, a North Korean defector and human rights activist. We follow Park as she struggles growing up in North Korea under the oppressive Kim regime, her dangerous journey to China where she encounters human traffickers and finally as she arrives to South Korea.

My Two Blankets by Irena Kobald, illustrated by Freya Blackwood (Little Hare)

This children’s picture book that follows the story of Cartwheel, a refugee from a country in Africa (it is not specified), as she moves to a new and unfamiliar land and her struggles to adapt to the western environment and language. As the blurb on the back cover of the book puts it, “This is a story about new ways of speaking, new ways of living, new ways of being.”

The Little Refugee by Anh Do, illustrated by Suzanne Do (Allen and Unwin)

The Little Refugee is based on the true experiences of Anh Do and his family who escaped from war-torn Vietnam in an overcrowded boat. This picture book not only describes their journey as refugees but also their struggle to acclimate to their new surroundings after arriving in suburban Australia. It highlights Anh Do’s struggles as a young boy with no knowledge of English and strange lunches.

Nida Fiazi has worked in the New Zealand book industry for the past five years as a poet, editor, reviewer, and advocate for better representation in literature. She is a Hazara Kiwi Muslim and a former refugee based in Kirikiriroa. Her work has appeared in Issue 6 of Mayhem Literary Journal, the anthology Ko Aotearoa Tātou | We Are New Zealand, and Poetry NZ Yearbook 2021. She is currently penning an opera with Tracey Slaughter.