Ngaere Roberts (Ngāti Porou) is one of our most prolific translators of children’s books into te reo Māori, having translated work from the likes of Joy Cowley, Gavin Bishop and Ruth Paul. Today Vini Olsen-Reeder chats to Ngaere about her storytelling process.

See here to read this interview in te reo Māori.

We’re doing this on paper, and not in person. At first I was a bit worried about that. Now I’m thinking it’s pretty special because I first met you through your written words! Today, our paper is our meeting place, and our two pens are our hongi! I’m from Tauranga Moana. Could you please tell me about yourself, who are, where you’re from and where your Māori language came from?

Kia ora rawa atu koe e Vini.

Firstly let me write here that I am humbled by your comments. We both know there is no better way to communicate than talking, face to face, but this is not always possible. So here we are communicating through the written word with the hope that we will achieve a similar outcome.

Although I have lived outside my own tribal area for some considerable time, my heart and love still goes back to my birthplace, to my cultural roots, to my home, to the very origins of my identity!

Hikurangi is my mountain

Waiapu is my river

Ngāti Porou is my tribe

Ngāti Rangi is my hapū

Reporua is my marae

Tū AuAu is my meeting house.

As for my reo, I thank my mother. My brother and I were not taught te reo Māori. We were fortunate that the Māori language was the only language spoken, not only in our family home but also with extended family members, who all lived nearby. This was the only language we heard, until we attended school.

Could you please tell me about your affinity with books, and what led you to be part of such a special and prolific few who translate books for our tamariki and mokopuna?

When I finished school my mum said, ‘You’re going to train as a teacher!’ There was no argument. In those days, you got told things once, and you just did it!

So teaching was what I did for years. Every teacher knows that reading is pivotal in education. I am not just talking about reading aloud, but all the different interrelated skills involved in engaging with written texts.

If children struggle with reading, it is more difficult for them to excel in education. So what teachers strive to do is to make sure that children enjoy reading and so develop their affinity for books.

I was one of those teachers.

Let’s talk about your translation work. When I read some books, I feel like I get to know a bit about the author. Is that true of translated work? Do we learn about the author, or the translator? Do you try to carry through the essence of the author? Or am I just imagining things?

That is a good question. However, I personally do not look exclusively at the author. I do pay a certain amount of attention to how appealing the story is, how the story is constructed, who or what the characters are, and so on.I then read the script, once, twice, maybe three times or until I can really understand the meaning of the story. Then I begin to translate.

With regard to your question about whether or not I follow the essence of the English author, I do not. This is simply because, English has its own inherent essence, and te reo Māori has its own unique essence.

You’re not just a prolific translator but a doctoral graduate from university as well. While you were there you published research around discourse analysis: the style, format and flow of stories. Does that academic personality help to inform your translation work?

The definite answer to that is ‘Yes!’

Linguistic theories are indeed relevant to the task before a translator. These theories encapsulate every aspect of language from its phonology, vocabulary, phrases, sentences and whole text structuring.

The correct application of all these language features results in clarity of meaning, for the reader or listener. This is paramount.

Many of your books are aimed at our youngest audience, our babies who pick up their first books. Your language opens the door for them to read in te reo Māori, which is so important. Do you actively gravitate towards books written for that age?

The books I translate are chosen by the publishers.

Having said that, there is nothing wrong with spending time on our babies!

This is, in fact, a very important time for mum, dad, teachers and so on, to read aloud, to share these stories, to discuss the colourful illustrations, to introduce Māori words, phrases and sentences to our little ones to enable them to hear the beautiful sounds of te reo Māori.

Having said that, some of your books are aimed at older children, say, those who’ve started school (like Melu). Does your translation process change between ages? That is, do they require different kinds of treatments?

No! The difference may be that the themes, the interest levels are quite different for children who are a little older. And it is this that dictates what kind of language is used.

We should not overlook the cognitive ability of our tamariki nohinohi and think that we need to simplify the language. ‘No!’ They will absorb whatever language they hear, if they hear it regularly, and if it is presented to them correctly.

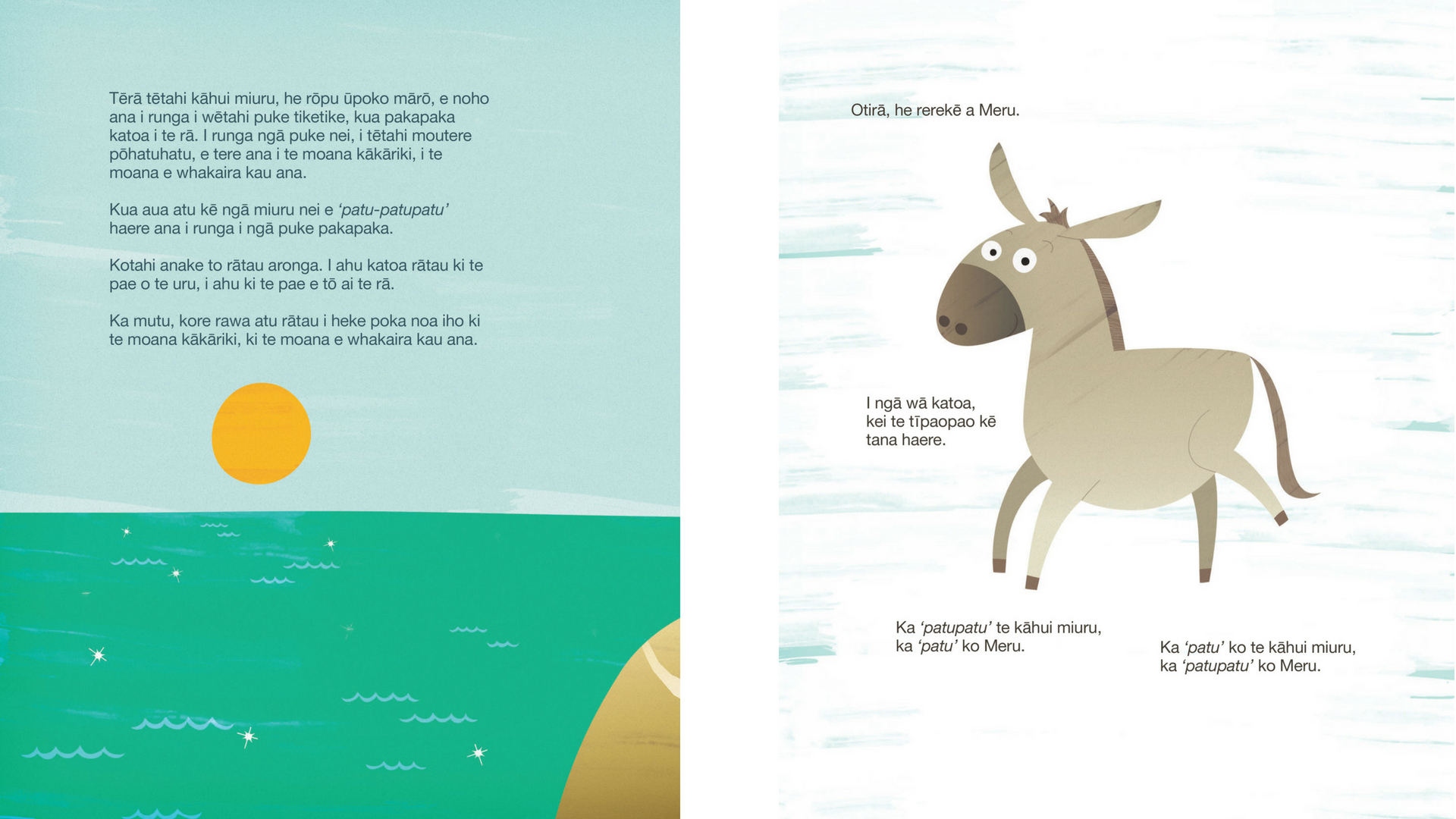

One of my favourite translations of yours is Ko Meru (Melu). I love the way you’ve translated English words like clippity-clop with patu-patupatu – these don’t just respond to the translation, but also translate the phonics. As a second language speaker who translates, I’m not sure it would be in my skillset to knead translations in that manner quickly. Do these kinds of translations take time for you to create, or are they things that connect to a native Māori speaker such as yourself?

Ko Meru is a great story, and you’re right! I believe that whatever is possible in English is possible in te reo Māori. I think what you’re talking about is ‘onomatopoeia’. Māori also has its own resonance and its own intonations. My approach, while I am translating is to consider the particular resonance. Then I convert that thought into a sound in my mind. From this I create a word which I hope will give meaning to the text.

A translator is often seen as a medium between two languages, the intermediary between understanding, and communication is the key goal. Translating books seems different to me, it’s less about ensuring an English and Māori reader can communicate, and more about ensuring both readers enjoy the text they’re reading in the same way. Do you think that’s correct?

I believe that you are making reference to two different contexts. However, for the translator, the two have the same overall objectives. They are:

- to correctly interpret the message/thought;

- to enable clear understanding by the reader /listener.

If the translator has this focus in mind, no matter what the context, then the third thing you talk about will eventuate, that is, you’ll end up with a really happy reader or listener.

It must be challenging to be a storyteller, when you’re telling the stories of others. That’s a responsibility you seem to carry with such ease. Are there any really challenging aspects to the job?

The main thing for me is to align the meaning of the Māori version to that of the English version. That’s probably the main challenge.

What’s next for you…?

Who can say?

And the last word is over to the storyteller. Is there anything you’d like to add?

We, the Māori people, must continue to work at the revitalisation of our noble language. This responsibility is on our shoulders! We must not leave it to others to carry this enormous task.

Mauri ora ki a koe Vini, otirā ki a tātau katoa!

You can read a version of this interview in te reo Māori here.

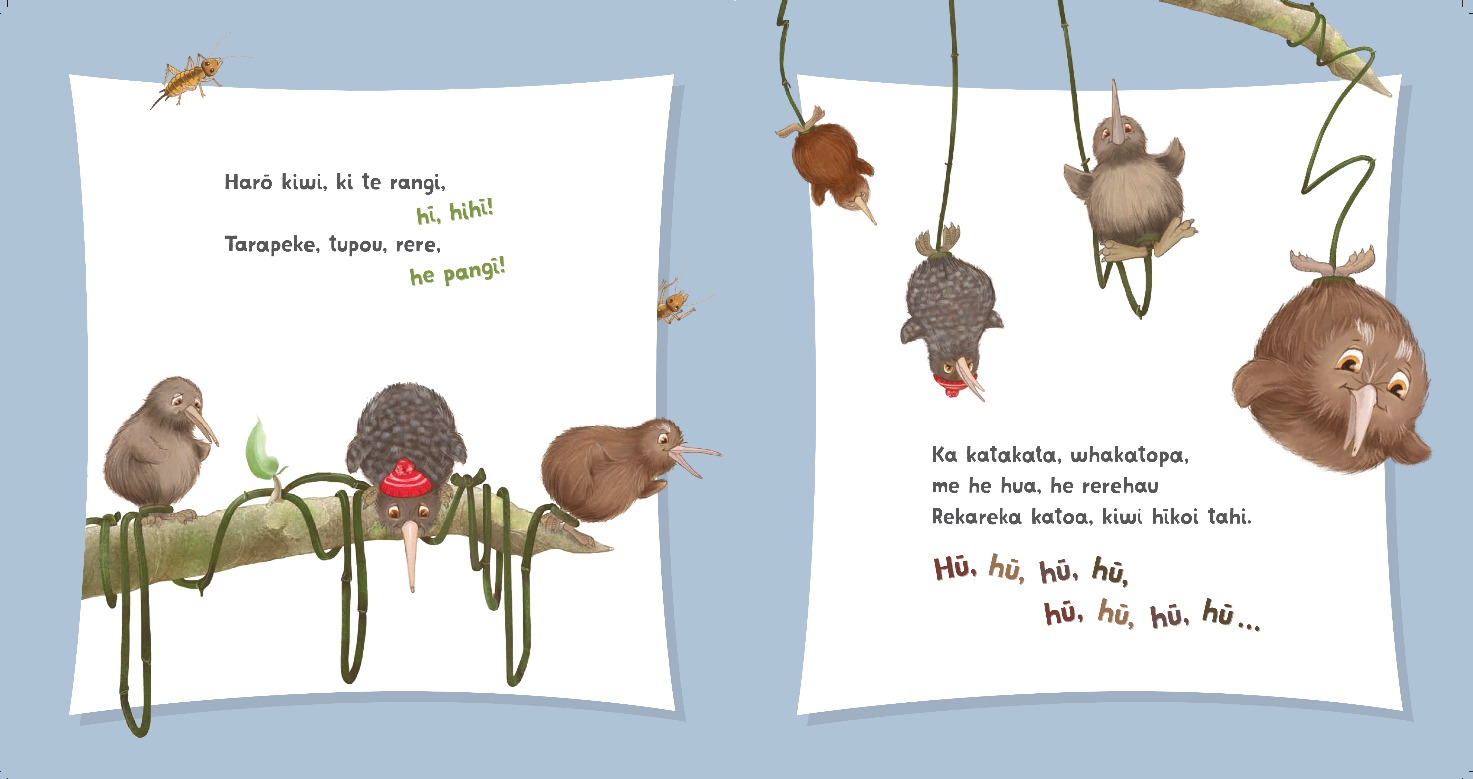

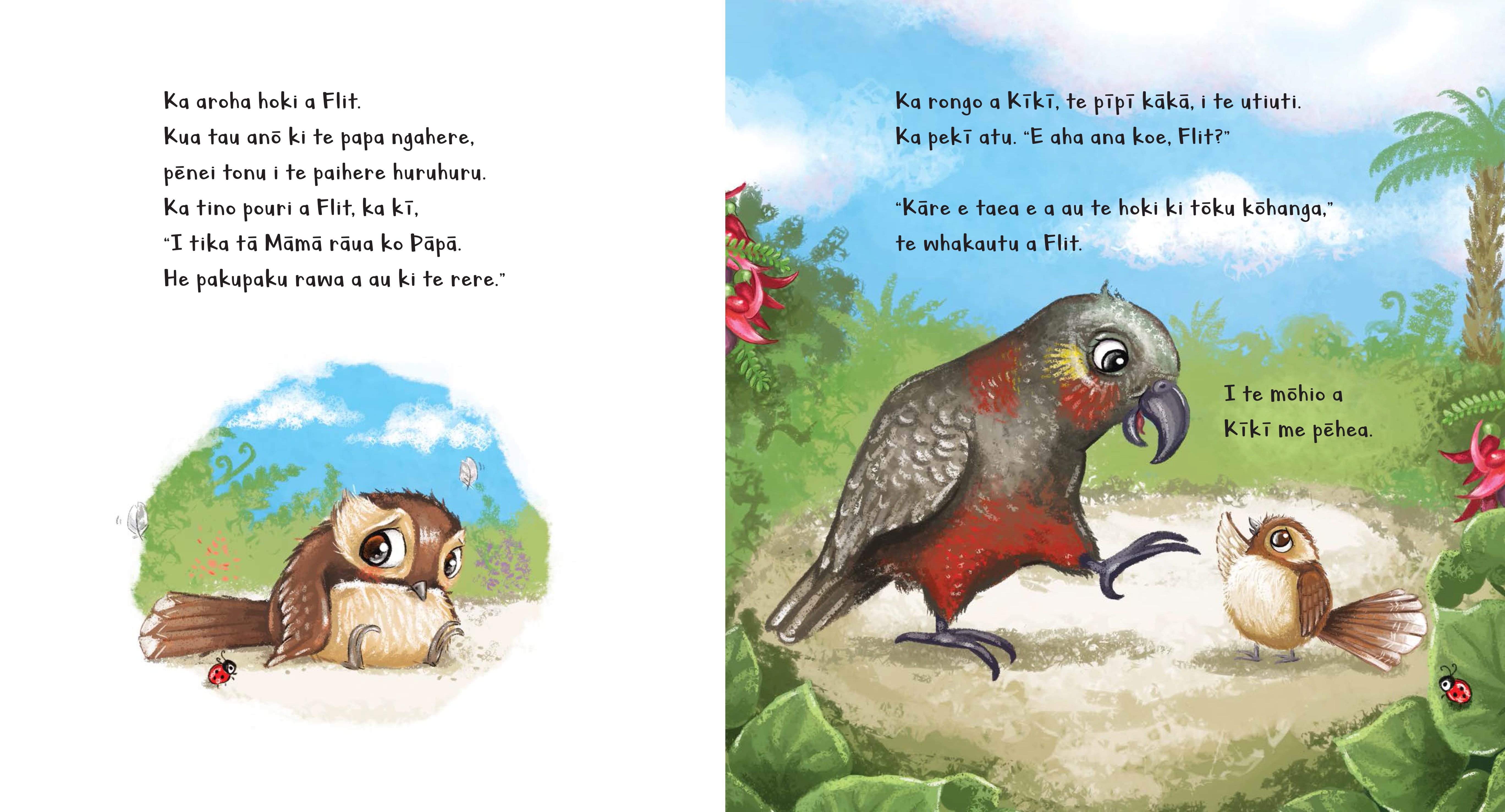

KO FLIT, TE TĪRAIRAKA: TE RERENGA I HĒ

nā Kat Merewether, nā Ngaere Roberts ngā kōrero i whakamāori

Scholastic

RRP $17.99

Vini Olsen-Reeder

Ko Koopukairoa te maunga,

Ko Waitao te awa,

Ko Rongomainohorangi te whare tipuna,

Ko Tūwairua te wharekai.

Ko Ngā Pōtiki a Tamapahore te iwi,

Ko Te Tauhou te tangata,

Ko Paraire te whānau.

Ko Vincent Ieni Olsen-Reeder ahau.

He kaiako reo ahau ki Te Whare Wānanga o Wikitōria.

He ngoke kai whārangi, he kaituhi, he ngākau nui ki te whai kia noho para kore.