Kate Duignan recalls two influential books from her childhood, Heidi and The Diddakoi, in this stunning personal essay about the importance of a child’s sense of home.

Kate’s new novel for adults, The New Ships, is out now from Victoria University Press. Novelist Anna Smaill has called it ‘a gripping novel about lost children and a very fine portrait of family life in all its beauty and betrayal. Intricate, compelling, and deeply moving.’

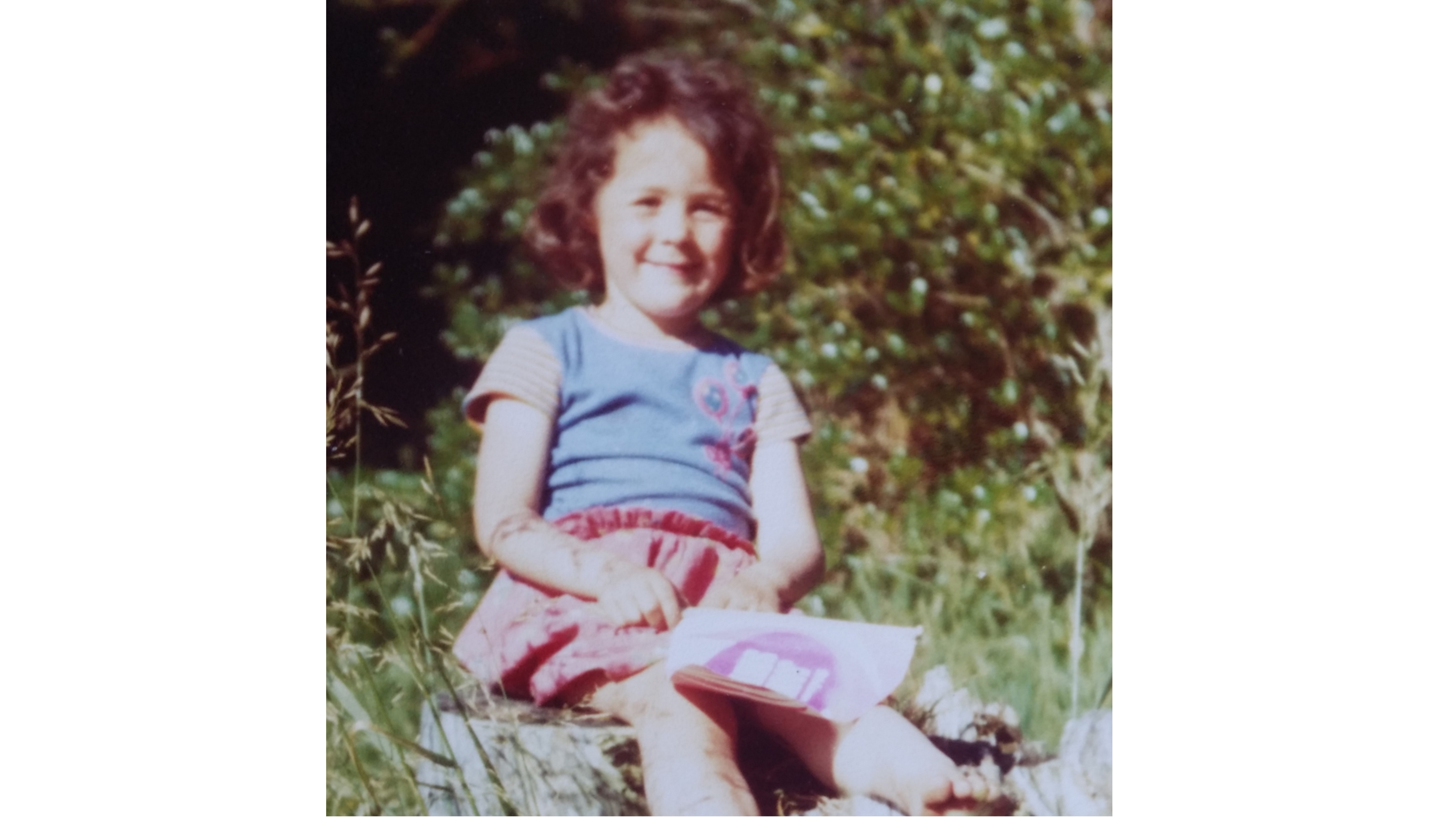

I think of my childhood as falling into three blocks. Before England, which is before the age of five-and-a-half, where time is swirling and vague and punctuated by only a handful of memories. Sitting on a rocking horse, and being given a cup of lemonade; a trip to Staglands, enormous horses and the terror of a swing bridge; orange, yellow and brown lines striped carpet in the classroom at Kura Street, and Mrs Stretch, my teacher, writing the word stretcher and making us see – look! – how it was just like her name.

Then England, which last until eight-and-a-half, where I am a schoolgirl at St Paul’s Roman Catholic School in Thames Ditton, Surrey, where I wear a blue jersey and a tie and a grey pinafore, where I begin my reading life, where I have, for the first time, private thoughts.

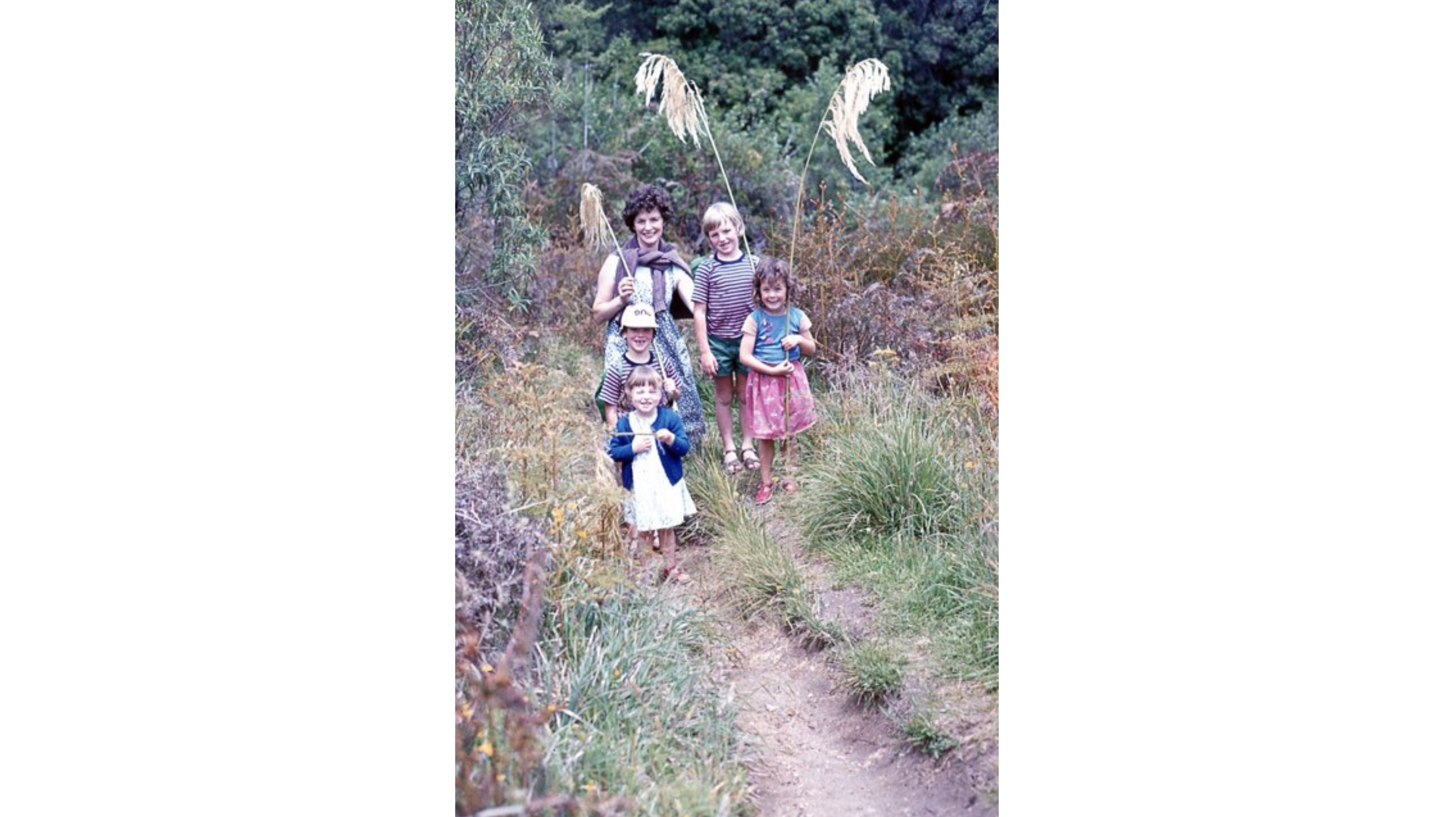

Then after England. There is a return to Titahi Bay, to the house my parents built, with the deck that never did get finished, walking down the gorse track to school on our own now, siblings and neighbours, twenty-cent mixtures and sherbet dips from the dairy at the end of each term. The movement from ages five to ten was home, not-home, home again.

This essay is about the books I read in England, and the child I was there. England, of course, wasn’t such a strange land. I spoke the language, I fitted in. (I developed a plummy accent, then lost it quicksmart when we went back to Porirua.) There were many continuities with home.

And yet. My birthday was now in spring, and Christmas was in winter, and there were squirrels and foxes and conker nuts, and you didn’t call it a park, you called it a common. There was no sea, and no beach, no toetoe and no island. There was no wind. There must have been some wind, I suppose. There was nothing like the wind at home. Also, I missed my grandparents.

My birthday was now in spring, and Christmas was in winter, and there were squirrels and foxes and conker nuts, and you didn’t call it a park, you called it a common.

The two books which I loved most in those years were Heidi by Johanna Spyri and The Diddakoi by Rumer Godden. There were plenty of other books – Famous Fives and Secret Sevens, Swallows and Amazons, the Noel Streatfeilds and E. Nesbits, the Narnia books, Roald Dahl. The standard canon of an English childhood, I guess. But from this vantage point, close to four decades on, it’s Heidi, and Kizzy from The Diddakoi, who I can feel along my bones and in my chest. I occupied these girls, I felt them, I was them.

Heidi is well known. The rustic idyll of the Swiss Alps where Heidi comes at five years old to live with her rough but kind grandfather, to sleep in a hayloft listening to the wind in the pines, to eat bread and goats’ cheese, to herd the animals to pasture. After a year or so, her aunt comes and removes her to Frankfurt, the noisy, busy city, where you must have table manners, where you are not allowed to run out of the front door and climb a church tower. Heidi, homesick, grows thin and pale, and starts to sleepwalk, frightening everyone in the household. The adults relent and she taken back to the mountain. Home, not-home, home again. When Heidi comes home to the wind and the pines and the hayloft and the grandfather and the goats’ cheese we feel such a deep relief: those grand rooms of Frankfurt were killing her.

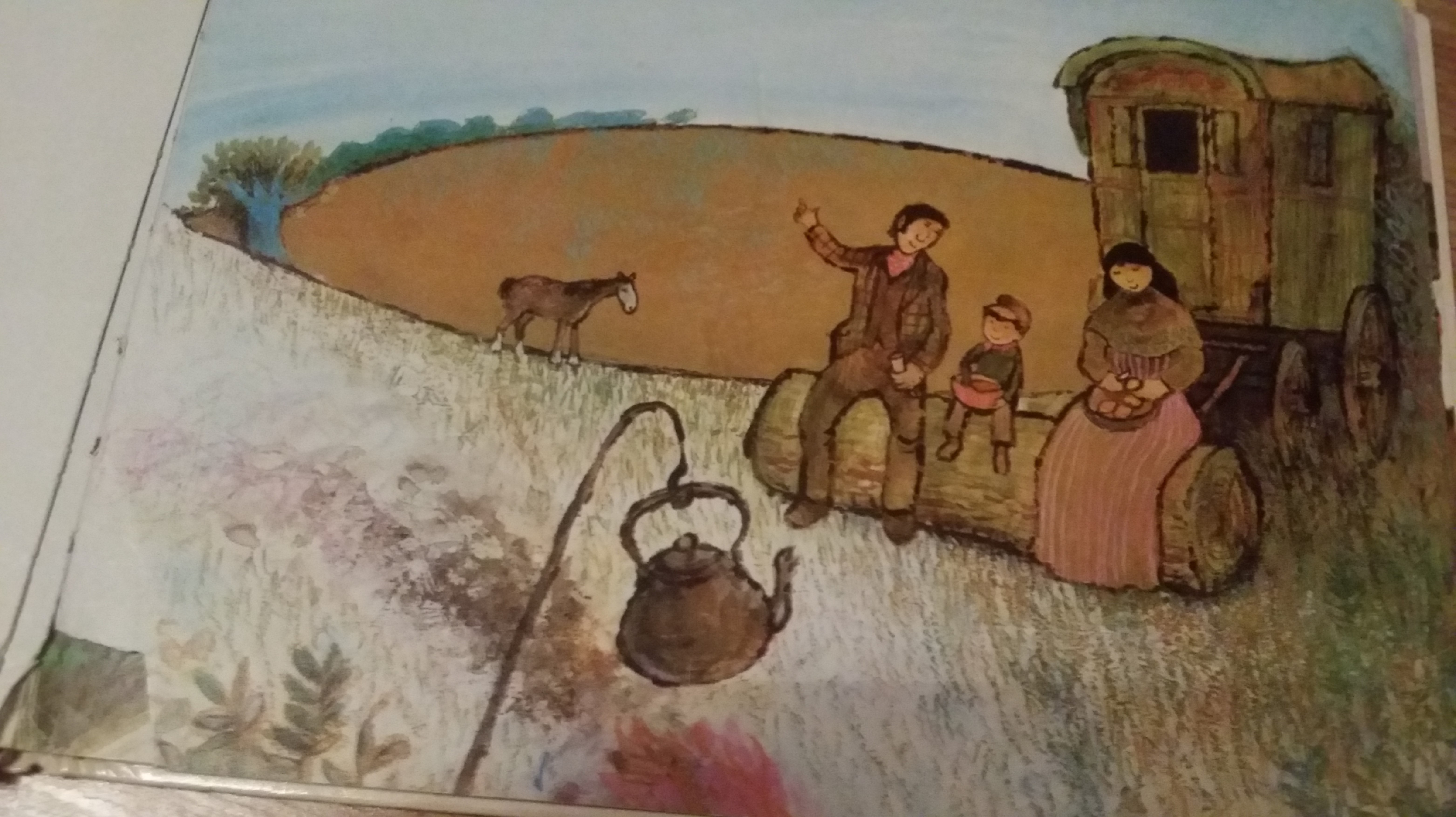

Kizzy Lovell in The Diddakoi is a gypsy child, who lives with her elderly Gran in a caravan parked in an orchard belonging to kindly retired Admiral Twiss, who gives Gran’s horse, Joe, free grazing.

‘Gran kept the caravan while Kizzy was away and went stick-gathering for the fire they lit and kept protected by a shelter of two sheets of corrugated iron, with sacks to keep out the wind. No one could build a fire like Gran; she sat on a bench, a plank across two piles of bricks; Kizzy had a fish-box that had McPhail and Son, Aberdeen stenciled on its side, but it was sturdy, the right size for Kizzy, and when it grew warm from the heat of the fire it gave out a sweet resin smell. … The black kettle sang on its hook, Gran’s kittle-iron, and presently they would have a cup of strong tea, drinking it in the firelight, their backs protected with a sack and Joe tearing up grass, keeping as close to them as he could get.’

I knew just how it was, the horse, the caravan, the fire and the kettle, because of the picture of the family in my book of rhymes, Bangalorey Man by Peggy Blakeley:

Little lad, little lad

where were you born?

far off in Lancashire,

under a thorn,

where they sup buttermilk

with a ram’s horn.

And a pumpkin scooped

with a yellow rim

is the bonny bowl

they breakfast in.

Gran dies early in the story, and so Kizzy is thrown into the care of the villagers, particularly busybody ladies on committees. All she wants is to live by herself in a caravan, but she’s seven years old: even I knew she wouldn’t be allowed to get her way on that.

It was quite a romanticisation to understand myself as one of these wild, untamed, free-ranging children. By the time I was five, my parents had built a comfortable three-bedroom house…

It was quite a romanticisation to understand myself as one of these wild, untamed, free-ranging children. By the time I was five, my parents had built a comfortable three bedroom house with views over Mana Island; I had a room to myself for that part of my childhood. I had grandparents with large family homes in Khandallah and Woburn, and while everyone enjoyed camping in the summer or a brisk winter’s day out walking in the Orongorongo valley, it was always home at dusk to the gas heaters and the six o’clock news on TV. But I did live near the sea, and I did go barefoot often. Sometimes as a child, the merest hint will do. I did just completely see myself as Heidi, as Kizzy. I hated Frankfurt. I also hated the girls at Kizzy’s school with their meanness, and their complex rules of what you were allowed to do, and what you weren’t, and all the ways you might be wrong.

‘“Those clothes smell,” said Prudence, wrinkling up her pretty white nose. They did, but not of dirt. Gran washed them often, hanging them along the hedge, while Kizzy wrapped herself in a blanket; they smelled of open air, of wood-smoke and a little of the old horse, Joe, because she hugged him often.’

Kizzy’s classmates are merciless, almost to the point of murder. It’s extraordinary to read some of these scenes as an adult in 2018. At the height of their cruelty the children, the girls (women and girls do not come off well in this book) lift Kizzy off her feet and ram her headfirst into a tree, almost breaking her neck. The adult who witness the scene, including Kizzy’s guardian, conclude that: ‘It’s a children’s war. Let the children settle it.’

‘Your dad wears a grass skirt and dances around a fire,’ the kids in Thames Ditton said. But my father mostly wore a suit …

‘Your dad wears a grass skirt and dances around a fire,’ the kids in Thames Ditton said. But my father mostly wore a suit, and took his tie off when he came home at night from his work at New Zealand House on the Haymarket in London, near the lions of Trafalgar Square. Also, the only fire from home I could remember was the huge gorse fire that had happened one night at the back of Onepoto; we had gone out in the dark to see it, and the fire was the same fire as the poem my mother read to me from our book (The Gorse Fire’, from James K. Baxter’s Poems To Read to Young New Zealanders):

Oh what a worry

When the gorse bushes catch!

Somebody careless

Has dropped a match…

And the crackling bushes

Blazed higher and higher

Up the brown hillside

Like a river on fire!

‘Your dad wears a grass skirt and dances around a fire.’ I knew what the kids meant, and I knew they were wrong. In fact, there was a heady rush in understanding how confused those English children were. I wasn’t Māori; and in any case, Tāne, Roimata and Te Reme’s father across the road from us at Mapplebeck Street didn’t wear grass skirts, or at least I’d never seen it; none of the Māori men that I knew in Titahi Bay did. It was a strange goading. I was being conflated with something that I wasn’t, but that I wouldn’t have been ashamed to be, and something which was being misrepresented in any case.

Mostly, though, I knew that the group had singled me out, had seen me as other, different, weak, ready to be picked on.

In my memory, a fierce egalitarianism had operated in the playground at Kura Street. Was it Ngā, the girl whose hands had been burned? The skin of her palms was scarred and thick. I had flinched once, when I was supposed to take Ngā’s hand in a circle game. I had flinched, or maybe I shook my head in refusal. I don’t remember how the kids let me know that this was wrong, that this was not how it was done, but somehow I was made to understand, and I bucked up and took Ngā’s hand: excluding Ngā would not be tolerated.

I remember… sometimes climbing to the top of the bars and hanging upside down from my knees, because that was the one trick I had that seemed to impress the English kids.

It wasn’t like that at Thames Ditton. It’s hard to be objective, but I have a sense that there was a strong heirarchy, and that for a long time I was at the bottom of it. Still, it was all rather mild. I was never Kizzy. I remember a vague misery, and avoiding going to school in the mornings, and sometimes climbing to the top of the bars and hanging upside down from my knees, because that was the one trick I had that seemed to impress the English kids. (That too was odd, because at Kura Street such a boring trick wouldn’t have even been noticed: back home several girls my age could do the death drop, hanging off their knees, then flipping off without using hands at all, landing on their feet.) Later on in England, there were real friends; one in particular, Olivia, who, like Heidi’s Clara, I didn’t want to leave behind.

Heidi and The Diddakoi both romanticize and, no doubt, sentimentilise poor, rural, subsistence childhoods. But my eight-year-old self simply loved those stories. They were my first experiences of novels explaining me to myself. They made me feel less lonely, and they helped me make sense of a homesickness that, in spite of many delights, permeated the three years I lived as a child in England.

Kate Duignan

Kate's novels Breakwater(2001) and The New Ships(2018) are published by Victoria University Press. Kate has completed a PhD at the IIML at Victoria University Wellington, and has published in Landfall, Sport, and various anthologies. Kate lives in Aro Valley, Wellington, with her partner and three children. Photo by Robert Cross