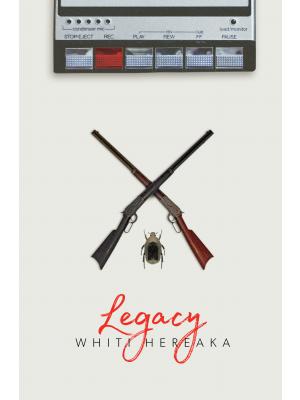

Novelist and playwright Whiti Hereaka is wondering where our Māori heroes were, in the commemoration of WWI. Her upcoming YA novel Legacy, will be released this month, and is based on the Māori experience of WWI.

I haven’t been to a dawn service in years. Decades even. I had attended Anzac services every year that I was a Girl Guide and there’s still a part of me that thinks: I’ve done my time.

The strongest memory I have of Anzac day is standing at attention for what seemed like hours and hours, shifting my weight between my feet as my legs got tired. Anzac day is the smell of Brasso and shoe polish on badges and shoes buffed to a high shine. It’s standing shoulder to shoulder in uniform, each of us blurring into the whole of patrol and company.

As I stood there I would let it all wash over me: the poems and speeches, the anthems, the ‘lest we forgets’ — but were we really remembering?

We all stood in front of the Memorial Hall — the Guides, the Scouts, cadets from the Army and the Veterans. One Anzac day, a cadet fainted as we stood. He was carried away as the service continued on, as the rest of us stood fast in formation. Thinking about that moment now it seems rather fitting for the events we were commemorating: human frailty barely acknowledged by the pomp of military ceremony.

One Anzac day, a cadet fainted as we stood. He was carried away as the service continued on, as the rest of us stood fast in formation.

The Anzac narrative was about “Kiwis” or “New Zealanders” — terms that are not really inclusive of Māori, so not inclusive of me.

Because of this, I never really connected with the Anzac story we learnt in school: none of it was made real for me. The story was too big to be human: the countries involved, the number of men who died; it was too much to comprehend. Or there was too much focus on detail: the guns, the uniforms; the train-spotting things that I’ve always found tedious. Anzac day seemed to be about biscuits and poppies but not really about people. Not people I knew.

Given my disinterest in the commemoration of WWI, it seems odd that I would write a novel about it. And yet I have. So how did it happen?

Some years ago, Brian Bargh from Huia Publishers rang me and asked if I’d ever thought about writing a book about the Māori Contingent in WWI. He thought there ought to be a novel about them. I’d heard of the Māori Battalion who had served in WWII — I’d spent some time during my day job at the time working on the Māori Battalion website.

I uploaded photos of headstones from the Commonwealth War Graves, and entered dates: births and deaths. I didn’t realise how it was affecting me until I went to waiata practise. I couldn’t get through the first verse of ‘Hoki Mai E Tama Ma’ because I was sobbing. The song and the work had made it real for me: each headstone was a young man who never returned home.

I couldn’t get through the first verse of ‘Hoki Mai E Tama Ma’ because I was sobbing… each headstone was a young man who never returned home.

The Māori Battalion are deservedly famous — but what about the Māori men who served in WWI?My curiosity about the Māori Contingent was piqued — here was a perspective on the Great War that I could connect to. I’d heard the rhetoric about WWI being an important part of shaping our nation: not only in our realisation that we were a nation onto ourselves, but also in how we’d relate to each other domestically. I look at it as the beginning of the Māori Renaissance: Māori asked to be recognised as equal to Pākehā in the war and beyond, and the frustration when that failed to happen.

Although the legacy of our war is not as obvious as the trenches still visible in Europe, one hundred years on, we’re still feeling the effects of that war. The Māori Contingent was made up of the first sons of Māoridom, the men who would be our leaders. Their deaths left great holes in their communities, and in our greater society.

We’ve come a long way since I was a kid in telling diverse stories. Now, there is more value placed on differing viewpoints. There seems to be confidence, that “Anzac” is robust enough to include the experiences of the “other”: Māori, Pasifika peoples and the conscientious objectors — that these experiences add to the richness and the humanity of the story; it doesn’t detract from it.

My novel Legacy is my attempt to answer to the invisibility of Māori in WWI. It is a novel that puts the Māori perspective at the heart of the story. I want young people to see the human story of war and how it has shaped their world. I also want them to think about the power of story — that how a story is told can change how people think about real, historical events. History is molded by those who tell it — so it’s vitally important to tell your own story.

I want young people to see the human story of war and how it has shaped their world.

It’s my hope that other writers will tell their tīpuna’s stories too and broaden our understanding of “Anzac” — to let kids like me see their role in our shared history.

Because stories can make heroes, but they can also make people invisible.

Editors’ note: The Reckoning is a regular column where children’s literature experts air their thoughts, views and grievances. They’re not necessarily the views of the editors or our readers. We would love to hear your response to any of The Reckonings – join in the discussion over on Facebook.

Whiti Hereaka

Whiti Hereaka is a writer of Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Arawa, Ngāti Whakaue, Tuhourangi, Ngāti Tumatawera, Tainui and Pākehā descent, based in Wellington. She is the author of The Graphologist’s Apprentice, and the award-winning YA novels Bugsand Legacy.Whiti’s latest novel for adults, Kurangaituku, retells the story of Hatupatu, from the ogress bird woman’s point of view.