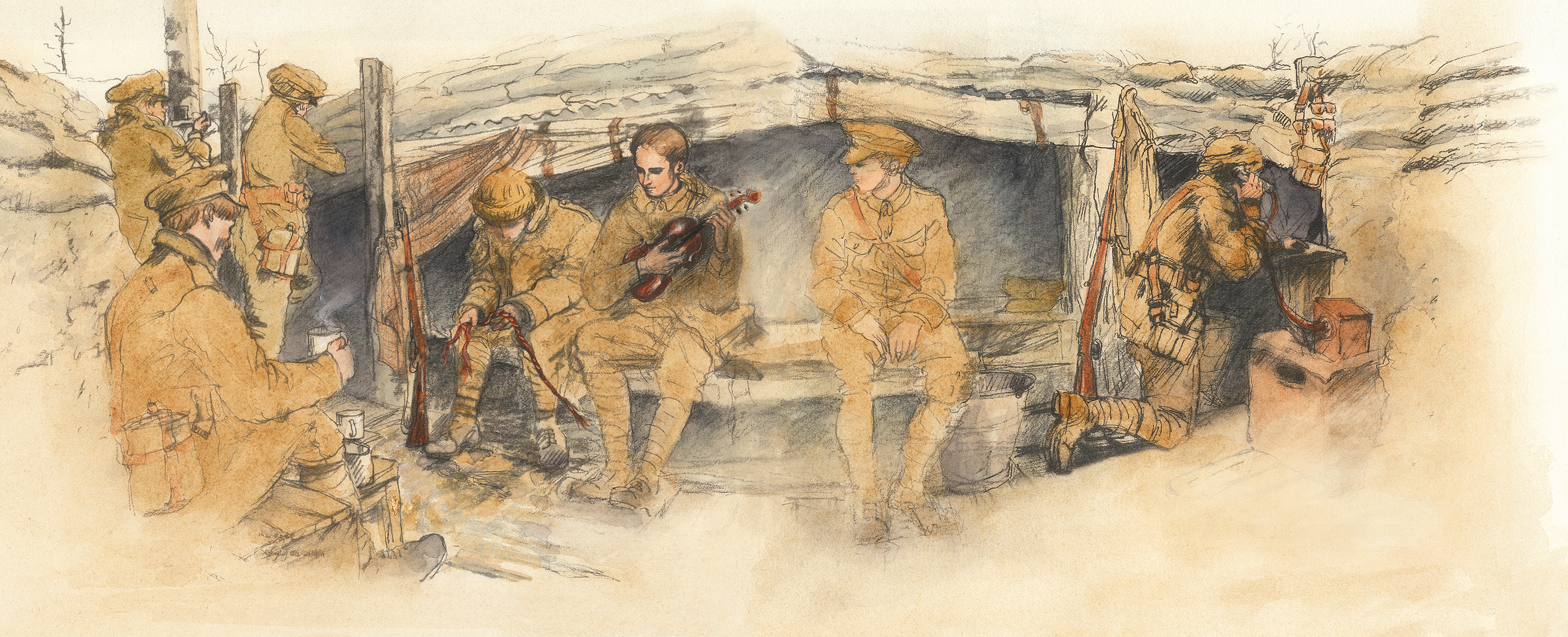

We present an interview between Robyn Belton and Jenny Cooper, on the subject of illustrating war stories, technology, (or the lack of it) and the misbehaviour of watercolour. Based loosely on their recently published World War I books: The ANZAC Violin: Alexander Aitken’s Story, written by Jennifer Beck, illustrated by Robyn Belton (Scholastic, 2018) and Bobby: The Littlest War Hero, written by Glyn Harper, illustrated by Jenny Cooper (Penguin Random House, 2017).

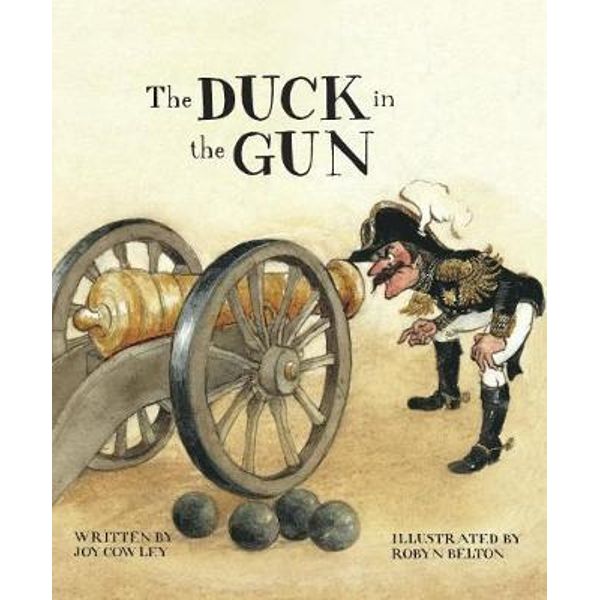

Robyn Belton is one of New Zealand’s best known and most accomplished illustrators of children’s books. After studying at the Canterbury School of Fine Arts under Russell Clark, Belton began her career in 1977 illustrating the School Journal. Belton’s first trade book was The Duck in the Gun, written by Joy Cowley, which won the Russell Clark Award in 1985, the first of several of her books to do so. With many major awards to her name, in 2006 Belton won the prestigious Margaret Mahy Medal. (bio source: NZ Book Council Writer’s Files)

Jenny Cooper: Let’s begin with a sensible question: Robyn, what do you love most about your job?

Robyn Belton: I love to bring stories alive through pictures!

I love the people I work with – many of them have become dear friends for over four decades. And I am no less excited by my work now, than I was when I began.

I do get challenged by deadlines, I love and loathe them at the same time. They seem impossible to meet! Yet my editors are so understanding.

J: You work in educational books as well as trade titles, what do you like about these?

R: Educational books are no less important than picture books. In fact, they deserve every bit of heart and soul, with attention to detail, as the longer trade books do. They are often a child’s first experience of looking at art, as well as being enticed into the world of reading – the magic of books.

J: What was the genesis of The Bantam and the Soldier (1996), which was published in 1996 and won Book of the Year in 1997?

R: This is a book very close to my heart. It arose out of a discussion Jennifer Beck and I had about family losses in World War I. She told me about a very special postcard that her family had kept. It was from her Great Uncle Arthur, who was killed days after writing the postcard.

For Jennifer, only as an adult did the significance of this strike home. The special postcard dated June 2nd 1917, with its poignant message ‘Give my love to Bertha’ relates to Jennifer’s mother.

In her Author’s Note in the book, Jennifer writes; ‘This is a story of what might have been.’

And I told her that although both my grandfathers had returned from World War I, they lost their sons in World War II. So I grew up never knowing my uncles.

In my country school, our headmaster asked my brother and me to lay the ANZAC wreath ‘because you are the family that lost all your uncles’. I was 12 years old. My grandparents tried to keep my uncles’ memories alive. I grew up knowing about the loss of all the young men. My father was the only one of that generation to survive.

We realised that many families in New Zealand and Australia would have suffered family losses such as this and we wanted to help children understand the significance of Anzac Day. It was the first New Zealand picture book to be published on the sensitive subject of the war. It coincided, by chance, with the 50 year lifting of the embargo on records from World War I.

It was the first NZ picture book to be published on the sensitive subject of World War I.

The President of the RSA came to the launch of the book, and I remember how honoured we felt when he said, ‘Thank you for telling our story. We want our stories told.’

The recent four year commemoration of that war has really brought many of these stories out into the open. And you have been a major part of this with your great collaboration with Glyn Harper!

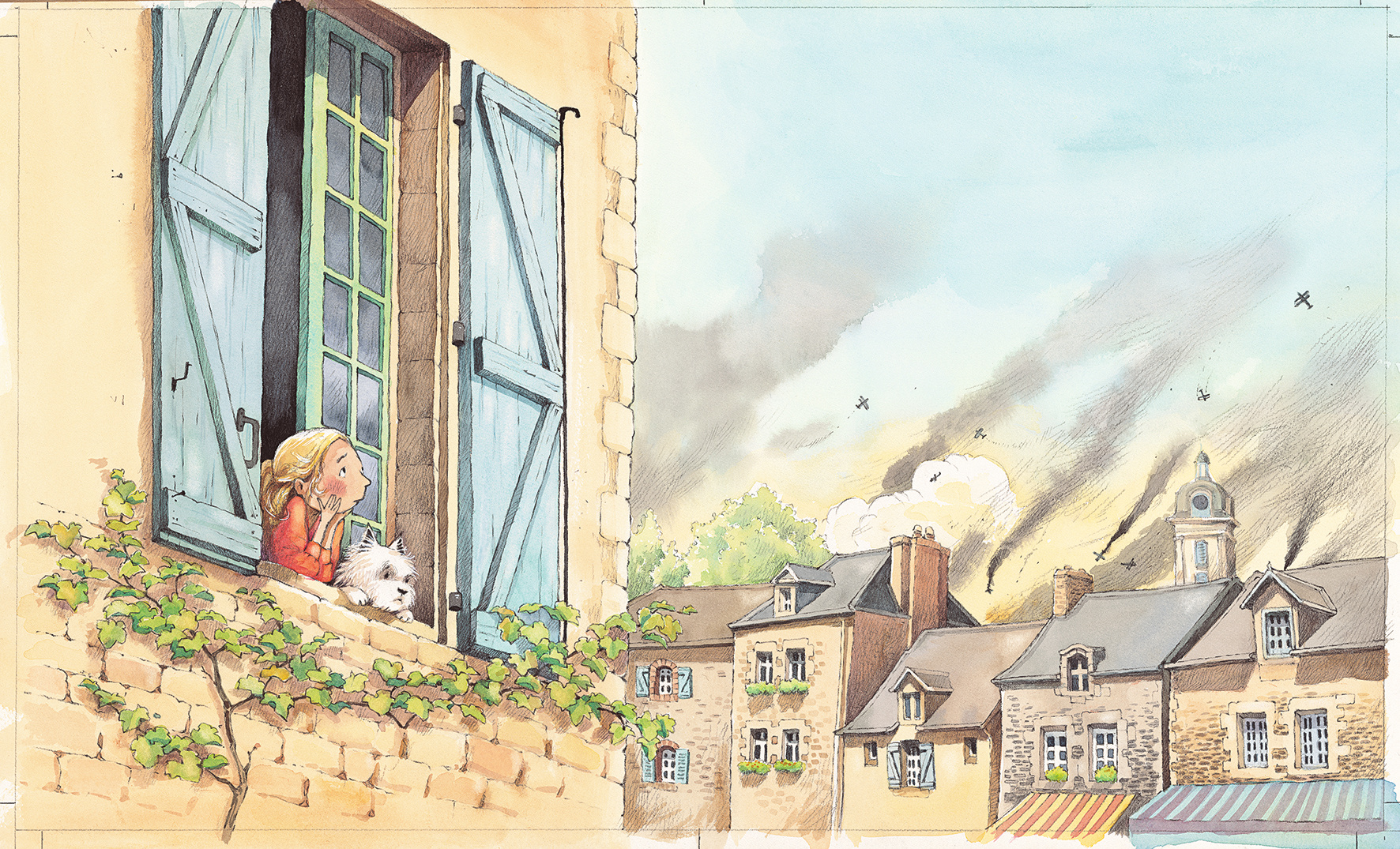

J: To be quite honest, I only accepted my first war book with Glyn because it was set in France, and I thought, old stone buildings! Geraniums! 1914 kitchen! I love to draw these things!

But Le Quesnoy was set in the (somewhat dark and wet) north of France, and I underestimated the amount of war that would creep into this book. I have learnt a lot since that first book, and hopefully deal with the complexities of illustrating war much better now. One is always aware of the war expert peering over one’s shoulder.

Le Quesnoy was my first World War I book, and I felt it was a bit uneven. I began with the female characters, which interested me most. They were loose and freely drawn. But as I did more and more research into the New Zealand Battalions, and looked at more and more images, they had an effect on my drawing, it became tighter and more detailed. I wasn’t happy, I felt I had lost control.

Glyn is great to work with. He writes simply, then leaves me alone to do what I want with the images. He has sent some uniform references, but other illustrators will know what I mean when I say they were of little use as they were illustrations! You can never trust an illustrator to get the details correct.

Glyn has an encyclopedic knowledge of every aspect of World War I, but he never gets picky or pedantic.

You can never trust an illustrator to get the details correct.

The internet has been invaluable. The whole of New Zealand’s war history is on line at Archives New Zealand including detailed day-by-day records of our battalions’ advances and retreats. It is fascinating and compulsive reading.

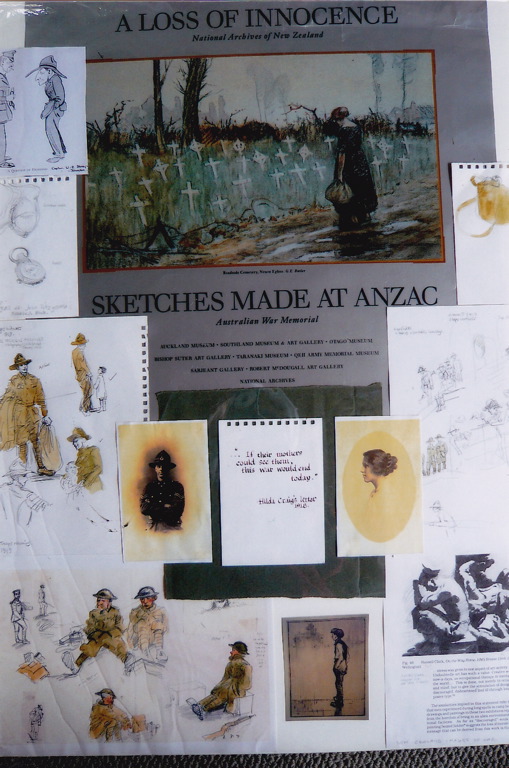

R: When I was working on The Bantam and the Soldier, in 1996, there was no internet, and there was no precedent for a children’s book about war. I was terrified of getting the uniforms wrong. There were no emails, it was all done with faxes, flying backwards and forwards between Jennifer B and myself, and using library books and museums for reference.

There were no emails, it was all done with faxes, flying backwards and forwards between Jennifer B and myself, and using library books and museums for reference.

J: I remember poring over it, as a very young illustrator, trying to work out your technique, what sort of paper you used, how you got those wonderful loose washes. Did you work at 100%?

R: I nearly always work same size, because if the artwork is enlarged, it appears looser and grainier.

J: I would love to be able to produce those loose free washes, my work just becomes tighter and tighter. I often work at 125%. But I am having terrible trouble finding good stretching tape. (Stretching tape is used when stretching watercolour paper before painting on it. This keeps the paper flat. The paper is soaked, then held down by the tape until paper and tape are at full stretch.)

J: Your new war book, The ANZAC Violin, where did this story come from?

R: This story has its beginning and its end in Dunedin.

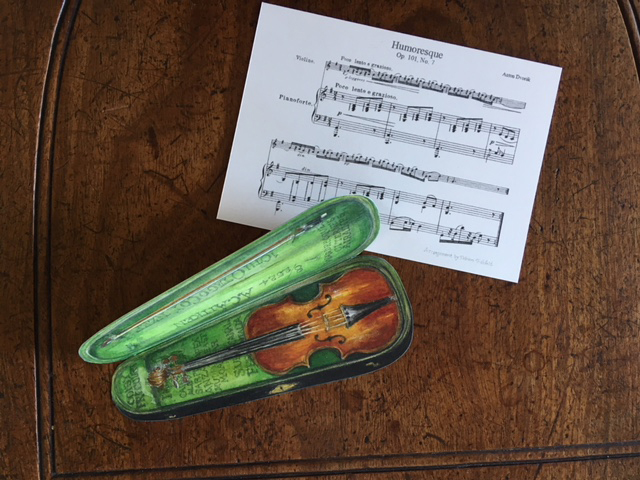

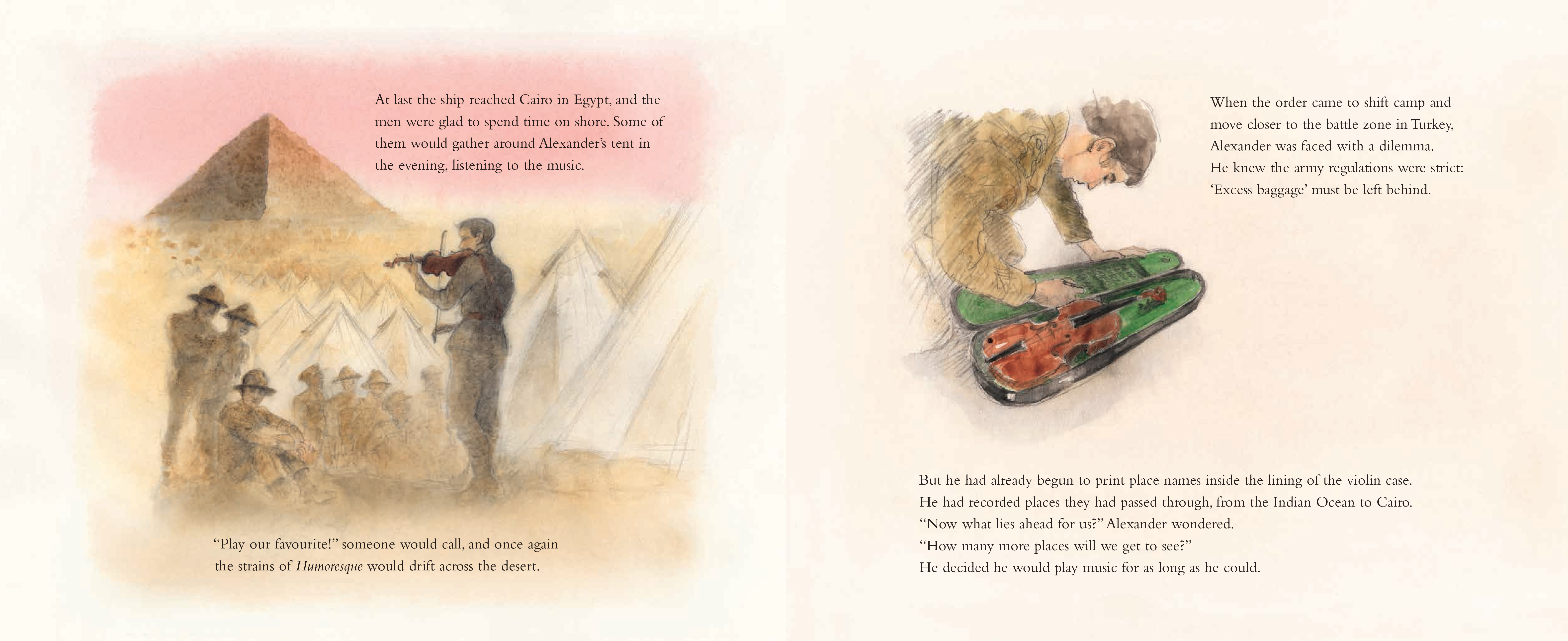

I had heard of the Aitken Violin, that it was a treasured exhibit at Otago Boys High School. Jennifer B had rescued a discarded copy of Gallipoli to the Somme, Alexander Aitken’s recollections of World War I, from her local library. We were both very moved by his story. We investigated further, went to see the violin and knew we wanted to bring Alexander’s story to light for a new generation.

Jennifer B and I greatly appreciated being granted the Creative New Zealand College of Education Children’s Writing Fellowship at Otago University in 2015.

Jennifer B came to Dunedin from Auckland to live for three months in the Robert Lord Cottage – we shared the residency, I continued my three months gathering images for the illustrations. But this was only the beginning!

We spent hours together in the Hocken Collection where Alexander Aitken’s letters are held. Being able to see Alexander’s handwritten notebooks brought an immediacy that was unforgettable. It was a great adventure. A rich experience. And we found more treasures than we had ever hoped for.

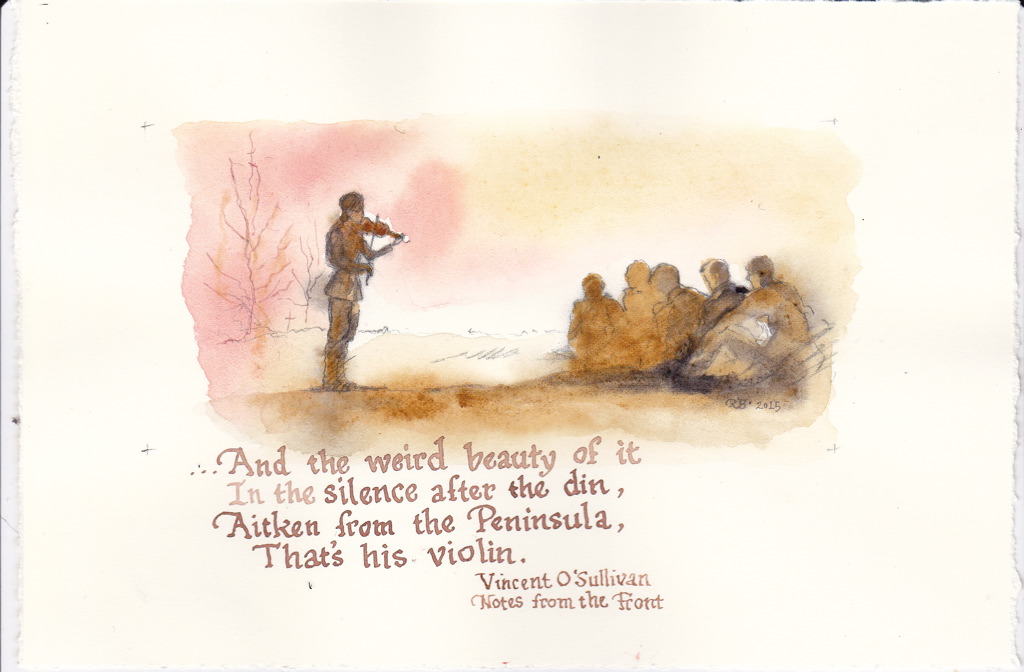

One of the highlights for me, working on the Anzac Violin, was knowing that composer Anthony Ritchie was working on his own project about Alexander Aitken. We was writing the oratorio Gallipoli to the Somme, commissioned by the Dunedin Sinfonia, for the World War I 100 year anniversary. We were working on our projects at the same time. So we often shared our findings.

This experience of working alongside Anthony took away the feeling of isolation and loneliness you sometimes get when you are deep in a book.

I was very touched by this review of The ANZAC Violin by Matariki Williams in The Sapling. She had it right on. Matariki writes: ‘For me, the illustrations for this book worked as a metaphor. Nothing is drawn with sharp distinction, the pictures often fade off the sides of the pages. The illustrations show us that war is indefinable, it is nonsensical, and that as memories fade, we need to remember through books like this.’

For The ANZAC Violin, I wanted the artwork to give a sense of another time. A time long ago. I hoped the watercolour washes would help suggest this.

I love the graininess of watercolour paper. There is nothing like the joy you get when the watercolour washes work well. Watercolour is so expressive. It can suggest the most tender feeling or evoke a truly dramatic atmosphere. You can create a storm by flooding the wet paper with colour. Indigo, Ultramarine, Prussian blue, yay! You have conjured up a storm!

I make a sort of ‘controlled accident’ with the watercolour, moving the wash of colour over the wet paper. I love those pigment names, so evocative: Burnt Umber, Raw sienna, Rose madder, Alizarin crimson, Cerulean blue…

I make a sort of ‘controlled accident’ with the watercolour, moving the wash of colour over the wet paper.

Of course, sometimes washes don’t behave and I have to screw up the paper, and throw it in the fire.

J: Do you often have to throw paintings out?

R: Yes, particularly if the stretching tape doesn’t work! For Herbert: the Brave Sea Dog, there was one painting, honestly, it took me seven times to get that painting right. After six failures, I got up at 4.30 one morning and had a go at conquering that particular page, and by 9.30am I got it right.

J: The colours you use in The Anzac Violin are wonderful. War books tend to offer a limited colour palette, which can be a bonus. It focuses the attention on the figures, without the distraction of bright colours. However I am never entirely happy with my ‘khaki’ colour. None of the references seem to agree.

Bobby was set mainly underground, in earthen tunnels, and was entirely peopled by men in uniform. My wonderful editor Catherine O’Loughlin diplomatically suggested I try to limit the amount of yellow and brown I painted with! We laughed about it later. It proved impossible. There is a LOT of yellow and brown in that book. Catherine’s suggestion explains why there are some rather highly coloured backgrounds used in Bobby. I was trying to break free of the mud and khaki.

Bobby the canary was a bit of a dilemma to work with. Canaries can be quite plain, thin birds, I tried to give him as much fluffiness as honesty would allow. As an illustrator I often find myself walking this tightrope between fact (canaries are boring, war is muddy) and fiction (canaries are cute, war can have a happy ending). Of course I am oversimplifying here, but much of what I do is editing, as there are so many possible truths about war, and so many details which might or might not be added. This is where the illustrator and author must to have a clear vision, otherwise the story we are telling can become unclear.

As an illustrator I often find myself walking this tightrope between fact (canaries are boring, war is muddy) and fiction (canaries are cute, war can have a happy ending).

J: Tell me about The Duck and the Gun – that is one of my very favourite books, and one I gave my own children.

R: Joy Cowley was distressed about the Vietnam War. How could a writer get an anti-war message to the next generation? This was the genesis of The Duck and the Gun. It was her first anti-war story.

Her ‘artist brief’ to me was to treat it as a spoof! And I loved illustrating that book. It was fun to give it a Ruritanian and operatic look. To send up the ridiculous aspects of war, the pomposity. I loved the humour and the compassion of that book. Joy and I were thrilled when some years later, the Hiroshima Peace Museum chose it for their Museum. It was re-published as one of 10 children’s books from around the world on a theme of peace. And more recently, Kate De Goldi chose it as part of her ‘Princely Package’ sent to Prince Louis!

One of my favourite war picture books is Rose Blanche, by Roberto Innocenti, and another is War Boy, by Michael Foreman.

J: I like Michael Foreman’s War Game. That book makes me weep.

R: Michael Foreman is wonderful, he sloshes watercolour all over the place.

J: Your styles are similar. Do you think, Is it appropriate to show children these images of death and battlefields?

R: I think children need to know about these things, but that is the illustrator’s task – to interpret in a sensitive way. A way that can be suggested rather than literally shown. The images need to be believable – not in a literal, photographic sense, but in an emotional sense, capturing the essence of the situation. (I think Michael Foreman said this.)

As an illustrator I have to be totally immersed in the story – I have to live it. All the while hoping ‘to catch the spirit of the thing’ (to quote Alexander Aitken)!

As an illustrator I have to be totally immersed in the story – I have to live it.

J: I try to keep one step removed from the stories I work on. All I can do, as an illustrator, is not to judge, but to bear witness, based on the best research I am capable of. By nature this is an exacting, and intense pursuit, and if I stopped caring, it would show in my work. Often the final product is a disappointment and I think, oh, if only I had another six months!

War stories in particular I find hard to work on. So many sad images to wade through. I only use a tiny part of the research, but once the images are seen, they can’t be unseen. There is one photograph in particular of a young man, completely covered in mud, perched in a water filled muddy trench, with his head in his hands. That image haunts me. It is an image of complete despair. And all those images of WW1 burns victims. There are no words for those.

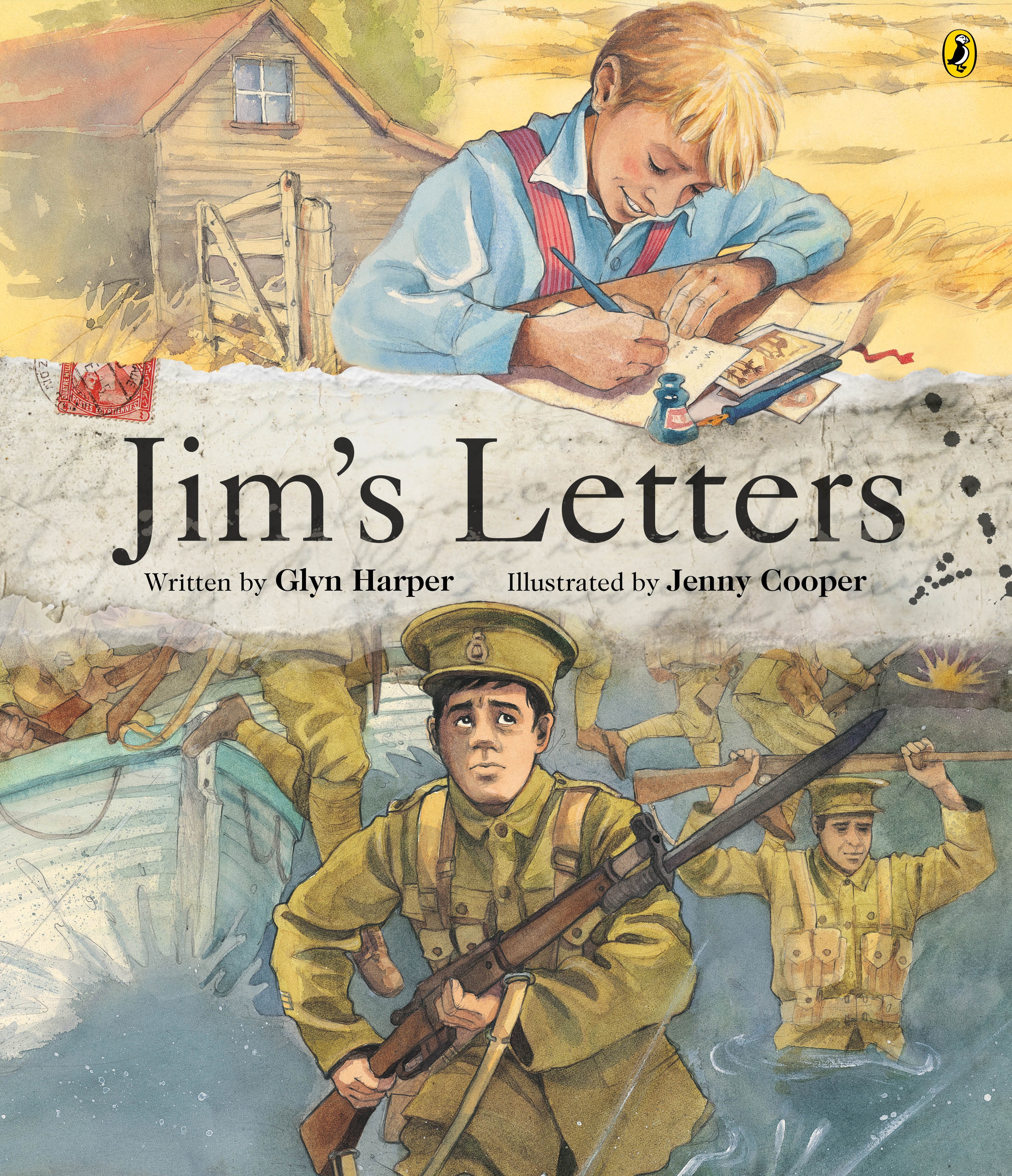

For Jim’s Letters (Penguin Random House) I hired models, so that the characters would be more consistent, and I hired the expertise of Graeme Barber, a local school principal here in North Canterbury, and World War I memorabilia collector. He has a whole garage full of artifacts, from guns to uniforms to every bit of kit carried into the trenches and onto Gallipoli beaches by New Zealand soldiers. We virtually set up desert camp, and trench warfare, in Graeme’s living room. Graeme, my model Sam, and myself, enacted scenes from the book for a whole day, and I took digital images.

That exercise has proved a wonderful resource. From the hundreds of digital photos I took, I would choose the best dozen or so, then cut and paste them in Photoshop. I then printed them out to the size I needed, and traced them, adding backgrounds etc. later.

R: I do the same but without Photoshop. I go through this ridiculous process with scissors and tape, printing out images, cutting them up, sticking them together and even taking them down to the local copy bureau to enlarge and reduce, to get the images I need at the right size. It is such a pain, I wish I knew how to do this on computer.

J: That is hilarious, that is EXACTLY what I used to do as well. So much paper everywhere!

But working from photographs has an interesting effect. The illustrations can become very tight, there is too much information. Once you learn how to draw puttees and canvas bags and ammo pouches it is very hard NOT to draw them in full detail. I have inadvertently become an expert on WW1 buckles and webbing. Every war book I do, I start out promising my editor it will be loose and expressive, and as the book goes on, the sheer weight of all the information simply overloads the pages.

Once you learn how to draw puttees and canvas bags and ammo pouches it is very hard NOT to draw them in full detail.

R: For The ANZAC Violin, I wanted to keep the spontaneity of the first sketches, so I took them down to my printer, who scanned them directly onto the watercolour paper. Then I drew and painted right into them. I think it looks a bit uneven, but it has kept things nice and loose.

J: My latest war book, My Grandfather’s War (Exisle Publishing) was a year late. I had just completed two war books back to back, this was the third in a row. It was too much – I had to take a break, and do some dancing cows. I felt so saturated with the tragedy and waste of war. War books especially can be sad and overwhelming to work on. If I ever get a whiff of Gallipoli commemorations, I just weep and weep, it is embarrassing!

R: Here are some quotes that I heard from Edward Blishen at an International Reading Association meeting some years ago which have helped me when I become depressed, struggling in the trenches, and facing this exacting task. These quotes give me heart, I have them on my wall in my studio. ‘Books aren’t just an optional form of entertainment, but are actually life giving things.’

And Shirley Hughes wrote ‘I hope books survive, they are wonderful pieces of technology.’

But I loved doing The Anzac Violin. I was almost three years ‘in the trenches’ but I felt it deserved that ‘war effort’!

Somehow, unintentionally, we’ve both become ‘war artists’. I tell myself that I’m being a Peace Warrior and hope like anything that it might do some good.

Somehow, unintentionally, we’ve both become ‘war artists’. I tell myself, that I’m being a Peace Warrior and hope like anything that it might do some good.

Bobby the littlest war hero

By Glyn Harper

Illustrated by Jenny Cooper

Penguin Random House NZRRP: $2000

Jenny Cooper

Jenny Cooperis an award-winning and prolific illustrator of more than 70 children’s books, and says she finds each new title “completely different and a new adventure”. In 2015 Jenny was honoured as one of New Zealand’s foremost illustrators with the presentation of The Arts Foundation Mallinson Rendel Illustrators Award.Jim’s Letters, Jenny's and author Glyn Harper’s memorable depiction of a World War One correspondence between two brothers, one a soldier in Gallipoli and the other at home on their Central Otago farm, won the Picture Book category of the 2015 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults. Jenny has also won a number of Storylines Notable Book Awards. Her illustrations forRoar Squeak Purrwere shortlisted for the NZ Book Awards 2023. Jenny lives in Amberley, near Christchurch.