By Whiti Hereaka

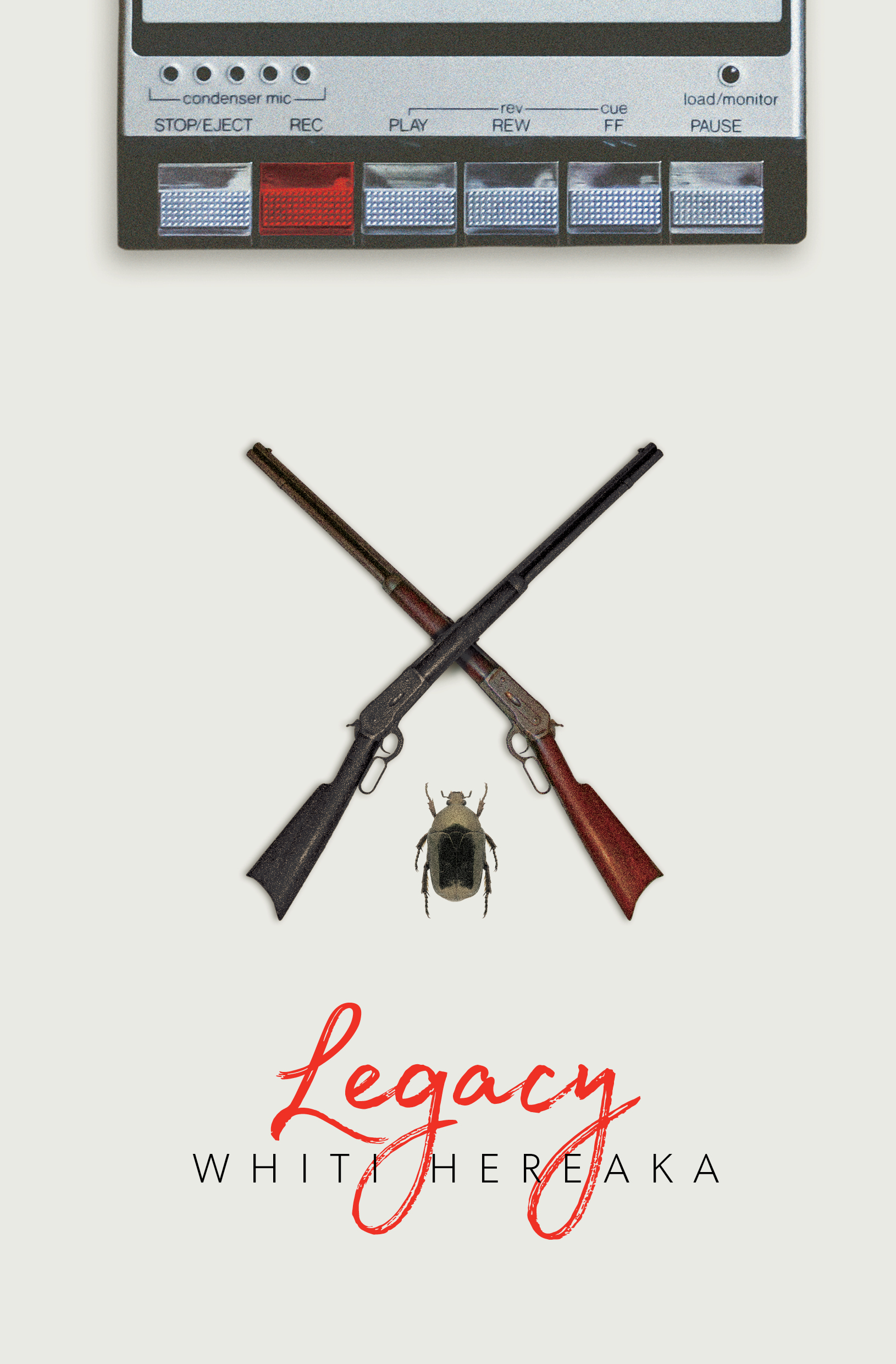

We’re pleased to present an excerpt from Legacy (Huia), a new YA novel by Whiti Hereaka (Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Te Arawa), the author of the multi award-winning Bugs (Huia).

Seventeen-year-old Riki is worried about school and the future, but mostly about his girlfriend, Gemma, who has suddenly stopped seeing or texting him. But on his way to see her, he’s hit by a bus and his life radically changes. Riki wakes up one hundred years earlier in Egypt, in 1915, and finds he’s living through his great-great-grandfather’s experiences in the Māori Contingent …

Chapter 4

2 APRIL 1915

Riki is aware of the world around him before he is aware of himself. It is disorienting; it feels as if he has emerged from a void, that until this very second he has been swimming in nothing, or rather, that until this second he was nothing. Unconsciousness seems to be worse than death.If the near-death stories are to be believed, then at least in death you are still aware of yourself – there are lights to follow and family to welcome you. Unconscious, there is nothing at all.

He hears the fall of footsteps around him: running, mostly. There is a little niggle in his brain that the footsteps sound wrong – the impact of them is soft, not at all like the click clack of soles against the road. There is no traffic, but that’s understandable because of the accident …

The bus. Riki remembers it all – it stretches out in his mind even though it only took a few seconds. He didn’t see the bus; he was looking down at his phone. But he heard its horn and the shouts of people on the footpath. He remembers being slammed in his side and the phone flying from his hand, and stupidly worrying that it would break.

He must have hit his head hard, that’s why he’s confused. The voices around him now are a mixture of English and another language he can’t quite place. And although the people around him sound panicked, they don’t seem to be panicked about him: the kid who was hit by the bus.

He opens his eyes, and it is darker than he thought it would be. How long has he been here, how long was he out? He starts to calculate in his head. It was just after nine in the morning when he was hit – surely they wouldn’t have left him on the street till evening. God, why does it matter what time it is? Why am I still on the street?

He groans as he pushes himself up to sit. At least he can move.He aches all over, but it doesn’t seem as if he has broken anything.He turns his head slightly and looks at the buildings, trying to orient himself geographically. Was he outside Kirk’s when he was hit? But this can’t be Kirk’s: that only takes up a block, and here the whole street looks old-fashioned. Where are the high-rises? The walls of glass and steel?

Where is he? He can’t think of anywhere in town that looks like this – not in his lifetime anyway.

Where am I?

Riki’s breath quickens. He stands up, testing his limbs for injury. He’s a little dizzy, but he can’t tell if it is physical or mental; it’s like he can’t process what he’s seeing, none of it seems real. He pats himself down as if to reassure himself that at least he is real. If he is honest, it is to reassure himself that he is alive.

He seems to have lost both his phone and his satchel. He’s sure he was wearing the bag across his body – how would it have come off on impact? He steps out on to the road, looking down for his phone. The road is unsealed – it is little more than compacted earth.

This isn’t right.

He has to touch his head again; he feels off balance. He looks up and sees his satchel – some guy is carrying it, the strap clutched in his fist. The guy is wearing a long tunic over pants – you don’t see a lot of guys wearing clothes like that in town.

‘Hey!’ Riki calls out. The guy turns around and sees Riki, then he runs.

‘That’s my bag!’ Riki runs after him, but he has no power in his legs,and his head spins. He stops to catch his breath, and the guy is lost in the crowd.

There seem to be heaps of men on the street – and there’s shouting, both angry and excited, like the crowd at a big game. People in fancy dress are spilling out of buildings: women in long skirts and camisoles, or those weird old-fashioned knickerbocker undies. Some of the men are dressed in long robes and turbans, and some of them are dressed like soldiers. Not in camo – old-school khaki.

The soldiers are chasing the other people out of the buildings; they’re throwing chairs and small tables, jars and bottles. Broken objects start to pile up on the street. Riki just stands and stares for a moment, then he sees his satchel in the gutter. He picks it up. The strap has been cut; that’s how it came off. The bag is empty – his wallet and books are gone. Worse, Te Ariki Mikaera’s diary is missing. Te Awhina is going to kill him when he gets home.

He hears a crashing above him – glass is breaking from an upstairs window. He looks up to see the end of an upright piano hanging over the street. The piano shudders as the men inside try to push it out.

‘Come on fellas, put your back into it.’ The voice has an Australian twang.

Riki can hear them groan as they push against the piano. The window frame splinters as it moves forward, and all of a sudden gravity takes over and it falls.

He scrambles away before it lands.

Hit by a bus and then crushed by a piano? Who am I, Wile E. Coyote?

He looks up to the window, or rather the hole in the wall, and sees three or four men pointing and laughing at the piano. It hasn’t smashed entirely – it landed on one corner, so its side crushed and the back has blown out. Some of the strings are breaking, so it almost seems as if it is playing itself. The whole scene reminds Riki of one of those old westerns – it is like the entire street is involved in some huge bar brawl.

‘Hey mate!’ One of the men from the window calls out. Riki looks up again. It’s hard to make the guy out against the light at his back. He holds up his hand and waves, and Riki waves back.

Riki lowers his hand and turns to walk away, and the guy calls again, ‘Boy! Wait there!’

But Riki keeps walking, avoiding the people on the street as much as he can. There are shouts of Gypo bastards! and Gypo scum! and women’s screams. There are men smashing whatever they can find, or looting from shop windows. There is a hint of smoke in the air – have they set fire to the piles of rubbish on the street? And then whoosh – a building goes up in flames. Whatever is going here – wherever ‘here’ might be – Riki wants no part of it. He’s not going to wait around on the street for some random.

He can’t walk very fast; he’s still feeling dizzy, and he can’t seem to get his feet to go in a straight line. People must think that he’s drunk, the way he’s staggering around.

‘Mate!’ Riki hears that guy again, and turns around. He looks into the crowd, but it’s a sea of khaki. He turns away again.

‘Pūweto.’ Riki stops; he’s not sure if he really heard it.

‘Pūweto! Te Ariki Mikaera Pūweto!’

It’s weird hearing his full name. Te Awhina only uses it when he’s in trouble – which he seems to be right now, to be fair. The guy even has that same scolding tone his mother uses. It’s like something deep inside him recognises the person in charge, so he stops and turns around again.

‘It is you, Pūweto.’

The guy pushes his way out of the crowd, and he and Riki stand face to face about a metre apart.

Reproduced from Legacy by Whiti Hereaka, published by Huia, 2018