In an interview with writer Sherryl Jordan as her two most recent works are published, Catherine Woulfe gets to the heart of what makes her work taonga.

I’m at a kid’s birthday party at McDonald’s and comprehensively hating it – the small talk, the noise, the lights – when a woman introduces her daughter. Elsha. Everything stops.

‘Elsha, you said? Not Elsa?’

The mum starts to explain. ‘Oh, it’s just a character from a book I really like…’

‘Winter of Fire,‘ I interrupt. ‘Yes. I wanted my boy to be a girl, just so I could call her Elsha.’

We grin at each other, entranced. Elsha rolls her eyes.

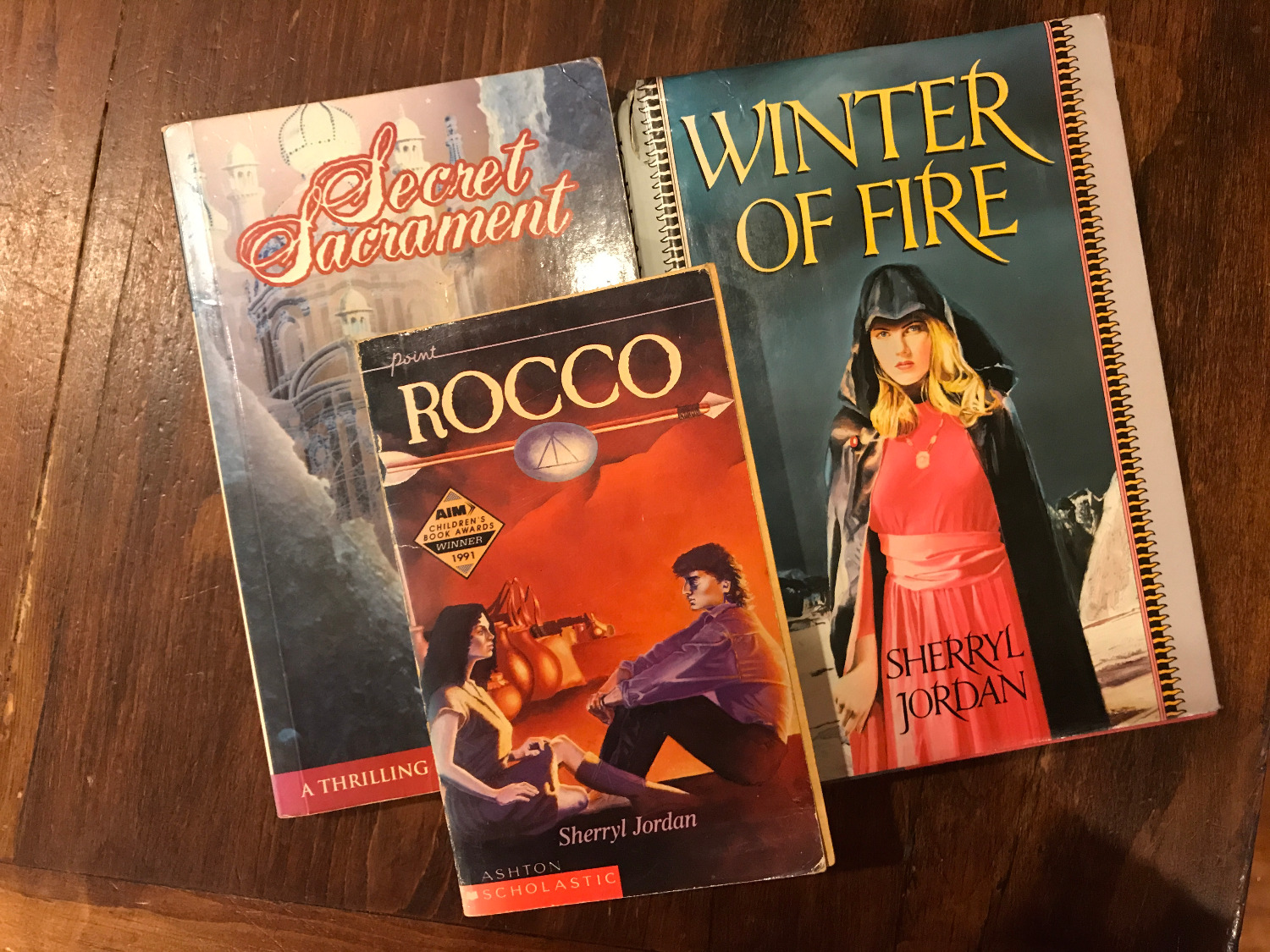

Elsha is the name of the woman – firebrand, lionheart – you get to inhabit when you read Sherryl Jordan’s 1993 YA Winter of Fire. A quarter-century on, this book still pulls the same trick it used to when I was an anxious, lonely kid. It makes my stupid brain shut up and be still for a moment.

A quarter-century on, this book still pulls the same trick it used to when I was an anxious, lonely kid.

When we meet her, Elsha is a slave. She works in a coal mine with a pick and a basket, wriggled deep into a seam, lying on her back in warm water.

On her sixteenth birthday she rebels. She stops work and she listens. She hears snatches of conversation, a child wailing, the thud of other picks.

‘And sometimes – some blessed, awesome times – there was a brief space where no sound was. Then I’d hear the soft breathing of the darkness, the throb and hum of the deep earth itself, the power of the firestones all around. Sometimes then it seemed as if my heart beat with the firestone heart, and I felt a oneness with the rock.’

It’s a moment that sustains Elsha. And although Jordan writes stories of turmoil and injustice, dragons and battles and plagues, every page of her books for young adults carries that sense of a powerful, meaningful peace – one that’s right there if you stop and listen.

…every page of her books for young adults carries that sense of a powerful, meaningful peace – one that’s right there if youstop and listen.

It’s also there in Rocco, the 13th book Jordan wrote and the first to be published, when a dying girl whispers ‘I do be scared’, and the teenaged hero cradles her, and says: ‘There’s nothing to be frightened of… Listen to Jakob’s pipes. The notes from them do be like silver birds, flying on the wind.’

It’s there in The Juniper Game, in a golden moment when Dylan and Juniper realise they can commune telepathically. It’s there in Tanith, running with the wolves.

It’s there in a last farewell between lovers Gabriel and Ashila, in the confronting, astonishing Secret Sacrament:

‘She looked into his eyes and saw that he was smiling, radiant; and there was so much love in him, so much triumph and joy, that she looked away again, unable to bear it.’

Radiance, triumph, joy: it’s everywhere, in all the slow smiles and sweet jokes and furs and fires and rituals. When Jordan uses words like “elated” and “awe” sincerely, without shying from them, she strips away the trivia. She transcends.

I still submerge myself in her books when I need to escape the ticker-tape that pulls through my head. It helps that the stories are set in other times, in landscapes of caves and falcons and smoke and wind. It helps that her female characters leave Katniss and Triss in the dust, and that Jordan gives her men – her boys, too – space for compassion, sensitivity, and grace. It helps that she centres the power of dreams, and of real human connections. But mostly, it’s that exquisite peace: the absence of a pick chip-chip-chipping away.

Funny, how things bubble in the subconscious. Jordan said in a Q&A with Christchurch City Libraries that she adored George MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin, in which miners dig into mountains, forging narrow passages through the warm and the wet.

During our phone interview, I read her this passage from that book:

‘If they stopped for a moment they could hear everywhere around them, some nearer, some farther off, the sounds of their companions burrowing away… Sometimes, if the miner was in a very lonely part, he would hear only a tap-tapping, no louder than that of a woodpecker…’

I gasped when I read it and now Jordan gasps too, marvelling.

‘Oh! Yes! Gosh, I’d forgotten that, because I hadn’t read The Princess and the Goblin since I was about eight or nine. Isn’t that amazing?’

The book shares other parallels with Winter of Fire: a setting of grey skies and grey mountains, a population divided into two profoundly unequal races. In both books, there’s also a simple trust in fate. MacDonald unspools a silver thread across his story for his characters to follow; Jordan fills Elsha up with courage and certainty and catalyses her with visions.

‘You can see how some people get accused of plagiarism, can’t you?’ Jordan says. ‘I would never have thought of it, if you hadn’t said that.

To be clear: I’m not going anywhere near plagiarism. What I’m interested in is synchronicity, serendipity, those deep quiet pools of the mind. Jordan, too.

‘I’m not one of these people who wants to talk about the weather, you know. I like to talk about things that really matter.’

So we talk about joy, and faith, and her humility at the way that her stories are gifted to her. Sometimes she feels like she’s taking dictation, she says, ‘the characters are doing their thing and I’m saying “Hold on, hold on, wait for me – I’m trying to write all of this down!”‘ She laughs. She laughs a lot.

…we talk about joy, and faith, and her humility at the way that her stories are gifted to her.

She remembers her friend, Joy Cowley, observing that switching between writing and the real world gave her jetlag. ‘And it’s true – the other world is just so true and so vivid and the voices are so real…’ ‘

In The Juniper Game, Juniper would visit medieval times in her mind, and come back high as a kite.

‘It probably is a bit of that, because it is living in that other world, with other people – it is in an other place, you know?‘

‘It’s the most amazing feeling. I think the only time I’ve ever had a feeling like that outside of writing was when my daughter was born. I can remember going for a little walk around the hospital and I was just walking on clouds… It’s a sense of absolutely ecstatic awe. It’s the heart of creativity.’

‘It’s a sense of absolutely ecstatic awe. It’s the heart of creativity.’

This interview was awhile in the baking. Last year Jordan steered clear, focused on dealing with breast cancer. For a time, her surgeon was concerned that an ache in her arm meant they were too late, that the cancer had already spread. She was 68.

‘I thought I really was going to die, and I actually was overwhelmed with the most incredible sense of joy,’ Jordan says. ‘I just absolutely felt that death was just the beginning of the greatest adventure… It was just a sense of being in a place and being loved and known absolutely. Which I am, now. But even more perfectly. It’s like Saint Paul said: now we see through a glass, darkly, then we shall see, face to face.’

Instead here she is, still looking through the glass. She lives close to the beach in Tauranga – ‘it is mostly solitude, rather than loneliness’- and locks her door so as not to be disturbed when she writes. For five years she has written and written, and worried that all her joy and light had put her out of touch with young adults – four more books have hit the ‘unpublished’ pile.

But two others have just been picked up, and she’s hopeful a third, Wynter’s Thief, about a water diviner, will be next.

I’ve been sent an electronic proof of Rafferty Ferret, Ratbag, Jordan’s new book for children, but a slew of visual migraines makes me reluctant to stare at a screen long enough to read it. Also, an admission: I’ve avoided Jordan’s younger books, the same way I ditched Jack Lasenby’s after discovering The Lake. What I want from these two is solemnity, grit. Not capers.

To the new YA, then. The Anger of Angels is Jordan all over: brave and thoroughly good young people, medieval Italy, grief and truth and light. Written from 2012, it forecasts these mad, Trumpian times. A Saint Melania is mentioned; there’s an evil dictator who lives in a golden palace, ‘a preening, powerful buffoon, violent and treacherous’. Freedom of speech is the central dilemma. Jordan’s tickled by the prescience.

She’s delighted by it all, actually – as Elsha puts it, ‘It is a wonder… to wrap up joy and grief in signs, for someone else to understand.’

Frankly, it’s a wonder Jordan’s still writing. In her work, healing is elevated, sacred. In life, over and over, it’s been mundane.

She overcame paralysing RSI to write Winter of Fire, scrawling Elsha’s first line in huge, wobbly letters. ‘Always at the heart of my life there has been fire.’

Then, in 1999: chronic fatigue syndrome. The accompanying brain fog meant Jordan was unable to read a novel, let alone write one. Simply taking a shower would leave her exhausted, nauseated and shaking. It lasted five years.

Last year brought cancer; now a disc has slipped in her spine. Jordan can only sit at her computer for half an hour at a time. Imagine the jetlag.

Jordan can only sit at her computer for half an hour at a time. Imagine the jetlag.

‘I don’t know when I’ll be able to get back to writing seriously, hour after uninterrupted hour,’ she tells me on the phone. ‘Probably never.’

A few days later, in an email, I ask her if that scares her. It did, during the chronic fatigue.

‘I will work it out, because I can’t imagine life without writing; but it is not going to be easy, perhaps not even enjoyable… I am trying extremely hard to be optimistic about it, though if I’m honest I’m dreading trying to write that way.’

So, perhaps there will never be another Elsha, another Juniper or Rocco or Tanith. But here’s the other thing about Sherryl Jordan: she likes to pit her characters against immense forces. She likes them to face failure, annihilation. But she never lets them get depressed.

And in the end?

‘I like them to triumph.’

Catherine Woulfe

Catherine is currently the editor at New Zealand Geographic after previously editing the books section at The Spinoff. She also edits 1972 magazine and has been a regular reviewer for the Listener.