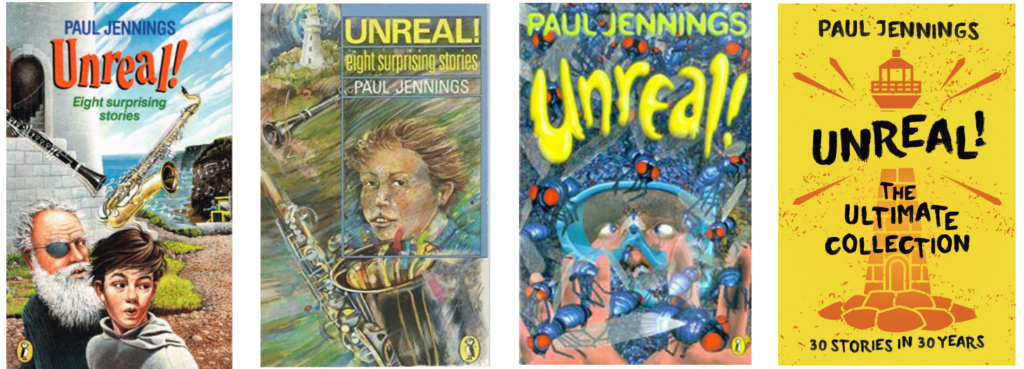

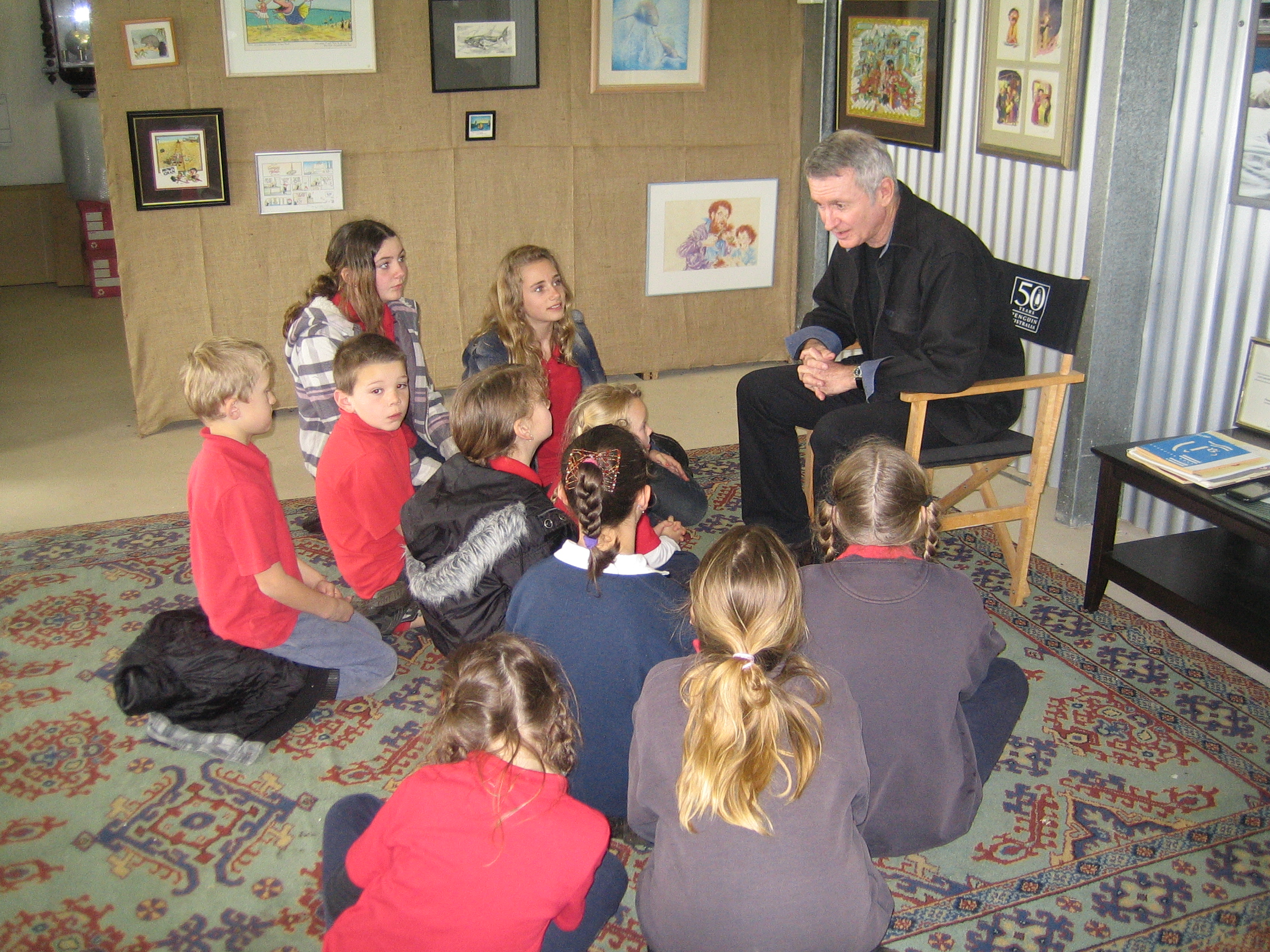

Paul Jennings is a legend of Australian children’s literature. He burst onto the literary scene in 1985 with his first anthology of short stories featuring weird, spooky and humorous tales with a twist, and never looked back. He has countless titles to his credit and drawers full of awards. From Unreal: Eight Surprising Stories, to the Rascal and Gizmo series, his stories have captured the imagination and inspired generations of kids around the globe.

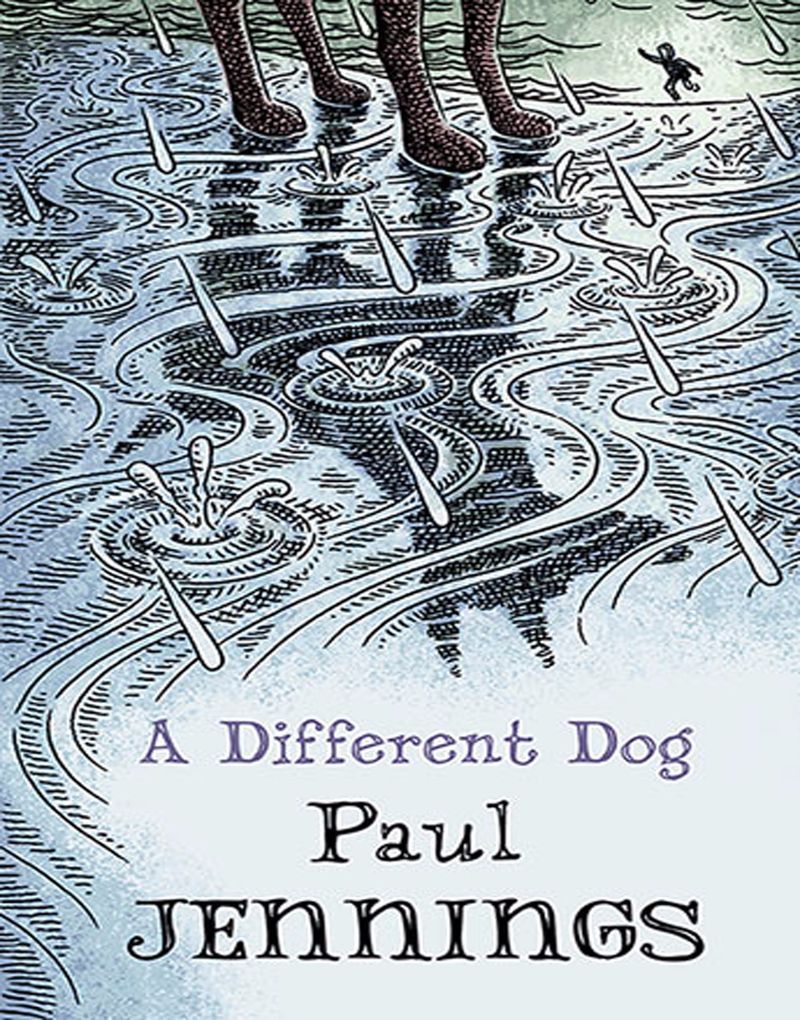

In his latest, thematically linked ‘Different’ series – A Different Dog, A Different Boy and the forthcoming A Different Land – he has raised the bar even further. Kyle Mewburn asks Paul about his background, philosophy and current works.

Kyle Mewburn: Like many children’s writers, you were once a teacher. What impact, if any – either positive or negative – has your teacher training and teaching career had on your writing?

Paul Jennings: My teacher training (1961–62) focused enormously on capturing the children’s attention by providing interesting and fun activities. Boring was bad. We were taught that you could put anything over if the kids were captivated. I have always believed since then that if children don’t like an activity it is almost impossible to get them to do it and if they love something it is difficult to make them to stop. Teacher training with its emphasis on using humour and well prepared, interesting lessons was an outstanding preparation for working with children.

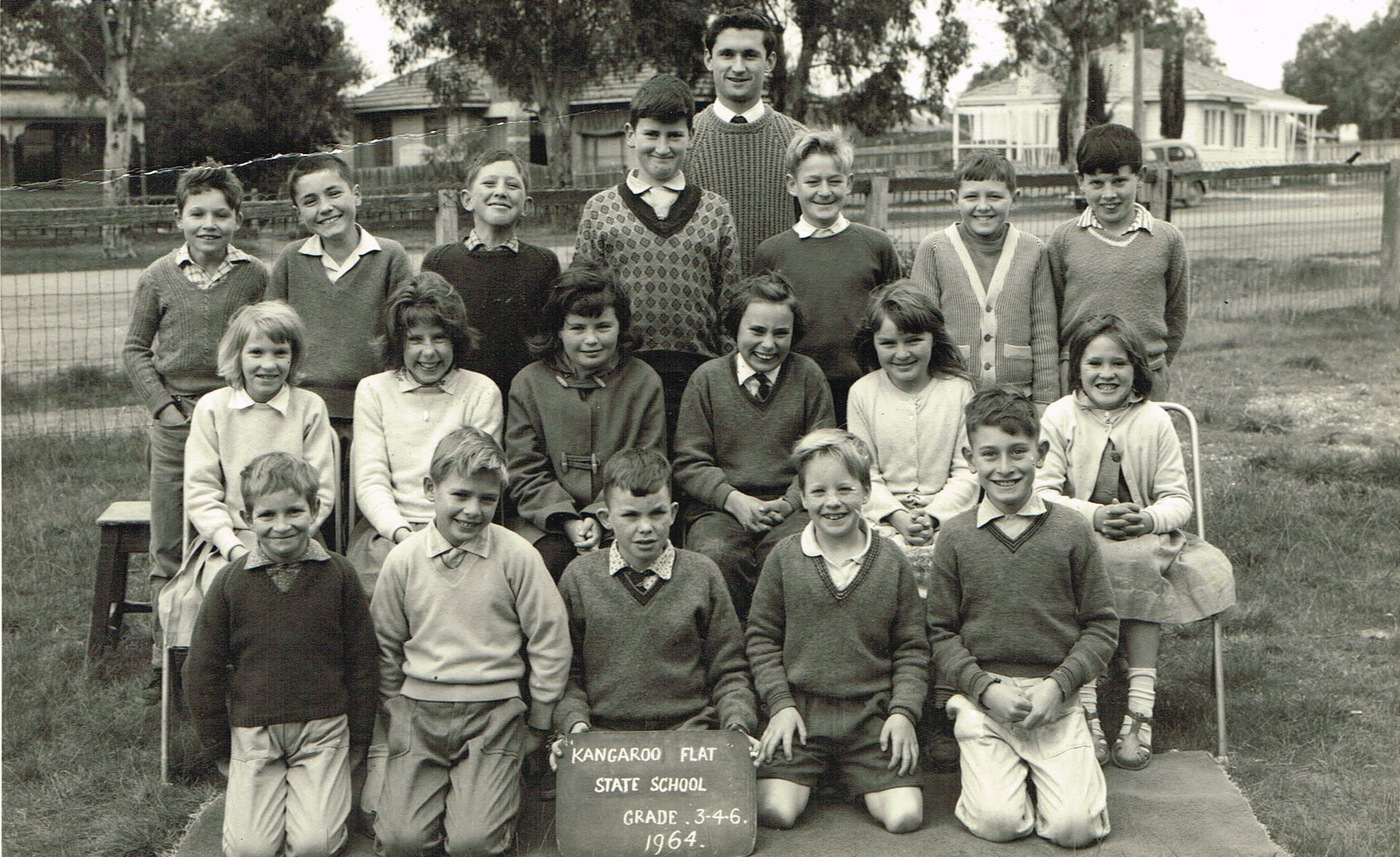

At the age of 18 I began my teaching career. My first class consisted of 15 children with intellectual problems. All of these students had reading difficulties. It was hard to find reading material that they could read but almost impossible to find anything that they wanted to read. This started me on a long journey.

K: Was there any specific motivation for you starting to write?

P: Twenty years after leaving teachers’ college I was a lecturer in reading education and was training student teachers myself. The same problem still existed – finding easy-to-read stories that were appealing to reluctant readers. So-called remedial readers which strongly controlled the text and difficulty levels were boring. I witnessed a child who was reading one of these little books throw it across the room. He shouted, ‘I’m sick of these piddly little stories.’ I picked it up and thought, ‘I could write a better yarn than that.’ It was a defining moment in my life. I decided to give it a go.

I witnessed a child who was reading one of these little books throw it across the room. He shouted, ‘I’m sick of these piddly little stories.’

First, I researched the factors that make text easy to read. I came up with a list of around 20 features – word length, sentence length, active rather than passive sentences, phonic complexity, avoidance of embedded clauses, use of repetition and rhyming, etc. etc.

I kept the dialogue descriptors very simple and avoided such devices as, ‘She exclaimed through clenched teeth.’ The great short story writer Raymond Carver only used ‘he said’ and ‘she said’ in his tales but no one ever notices this. I mostly use a new sentence to mark each new piece of dialogue. I try to keep everything simple and clear.

But I never cling to these rules. I swap them around and do break them now and then. Sometimes I add a few difficult words. However, I set each one up so that the child can make a good guess at its meaning, e.g., ‘He was locked up in a cell.’

I chose short stories because I like them myself but mainly because they give a quick reward to struggling readers. I broke the stories up into short chapters which break at an interesting point and make the reader want more.

My motivation was to provide stories that were easy to read and interesting enough to suck in reluctant readers.

My motivation was to provide interesting stories which were easy to read and interesting enough to suck in reluctant readers.

K: And did you start by writing the kind of stories that ended up in your Unreal series, or did you dabble in other genres?

P: I didn’t dabble in other genres before writing my children’s books. The only piece of non-academic writing I had tried before this was written for the Australian Women’s Weekly when I was 12 years old. It was rejected and I gave up, believing that I had no talent. I was nearly 40 years old when I tried again.

K: Having grown up myself in Australia in the ’70s, when writers such as Patricia Wrightson, Colin Thiele and Ruth Park ruled the roost, your Unreal stories must have swept across the literary landscape like a bushfire. Given the literary environment at the time, how were your first stories initially received by publishers?

P: I sent copies of three short stories to six different publishers. The first four replies were rejections. The fifth was a qualified acceptance. Penguin Books told me that if I could give them five more similar short stories of the same standard they would publish them. After I finished another three stories they gave me a contract and an advance of 400 dollars. I still have a photocopy of the cheque on my study wall.

For a year or so I hardly ever saw the book (Unreal) in a shop. Then I started getting letters from children in schools. Some from Western Australia, some from Queensland. It even sold in New Zealand! But I didn’t really realise that something was happening until it hit the bestseller list and a reprint was ordered. Soon after that I was offered a four-book contract and my life changed forever.

K: Your stories are often quite dark – or at least have a darker tone or theme – but, weirdly, I remembered them as being more funny than anything else. In my head you were a writer of humorous stories. Yet on re-reading them, I’m left with a much more complex sense of your writing. How do you describe your stories and yourself as a writer?

P: My early short stories were mostly designed to be humorous because children love to laugh. Sometimes the tales were not funny but they always contained surprises, adventures, unexpected developments and took the children into worlds that were quickly disappearing in reality – contact with nature and danger. I call it safe danger. Like climbing trees and bringing junk home from the tip. All these things I did deliberately and consciously.

But there is something else there beneath the text and for many years I was not even aware of it. That is the role of the unconscious mind. I am attracted to Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious which connects us all to a world of deeper truths of the type that underlie traditional fairy tales and myths and legends. A darker and also a light-filled side to human nature which we all share. Even children are dimly aware that they have sometimes, ‘Met a man who wasn’t there.’ The notion that there is something disturbing in our society and inside ourselves.

I am attracted to Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious which connects us all to a world of deeper truths of the type that underlie traditional fairy tales and myths and legends.

When I finish a story I sometimes pick it up and exclaim, ‘Oh, now I see. That’s what it’s about.’

A therapist once told me that he had never met anyone whose unconscious mind was as close to the surface as mine. An observation which is possibly a little scary. But yes, I do acknowledge that dark connection with the world of Cinderella, The Little Match Girl and Sleeping Beauty.

K: Your protagonists are primarily boys – often boys who don’t quite fit in, or are from single-parent families etc. Is this a conscious decision?

P: The single-parent families in my stories are quite deliberate. I was once a single parent and I like to present these families as normal. Also, I have to confess, that it is easy to write a story with fewer characters to describe – If the plot doesn’t need them I don’t put them in.

I mostly write about boys because I was a boy and I can get inside my childhood skin when I write. I don’t think girls mind this. I used to read my sister’s Anne Of Green Gables books. I do have some stories with girls as the main character.

K: Your voice is generally first-person – so could you possibly share something about your approach to discovering, or uncovering, each narrator’s voice.

P: I use the first-person voice a lot because it is easier to follow. All the ‘I did this and I did that’ make it quite clear what is going on. For more complex stories I use third person but, as in my ‘Different’ books, I only enter the mind of the main character and imply the feelings and thought of the others. And of course, the dialogue can always allow the secondary characters say what they feel.

I only enter the mind of the main character and imply the feelings and thought of the others.

K: Your stories almost invariably have a twist, which made me wonder about your creative process, and how you meld the elements together. How much do you plan your stories? What generally comes first – the story or the twist?

P: My earlier stories were always tightly plotted with the twist and the plot worked out before I started. My editor of 30 years (Julie Watts) once pointed out how much my stories change between drafts and as I was writing them. I gradually stopped the detailed planning and trusted that I would get a twist as the story developed. Now I always start with a small incident and see where it takes me.

K: Given your series usually have a theme – your current series focusing on difference, for example – how much planning or thought goes into creating a sense of cohesion across the series?

P: The three Different books happened by accident. A Different Dog was given its title because of the play on the word ‘different’ in its meaning of ‘changed’ rather than ‘not the same dog’. When I wrote the book A Different Boy, I realised that the new story fitted this play on words perfectly – the twins in the story are not the same but different people. I have just finished writing a sequel to this book about the main characters and their new life in Australia. I just had to call this A Different Land.

It was not my original intention to write a series. My editor, Julie, said to me, ‘Paul, we just have to know what happened to these poor people when then arrived in Australia.’

She was right – as usual.

K: Your writing is incredibly fluid and a marvel of efficiency. Every sentence, every scene keeps the story ticking over and compels the reader to turn the next page. How much of this is intuitive, and how much is the result of hard work, editing etc? How much editorial input do you actually receive? How valuable do you find such input?

P: I am heavily edited. I write at a furious pace and don’t spend as much time correcting my work as I should. My main mistakes are semantic ones. Julie once commented that they are the hardest errors for an editor to find. I constantly do things like describing five boys in grade six at the beginning of the story and mistakenly change it to six boys in grade five at the end.

Julie often works with me right from the original concept. She has also suggested books that I might think of writing like Round The Twist and the Rascal series. She read my first unpublished stories and was present at my first visit to my publisher over 30 years ago. These days she edits freelance and I am lucky enough to still have her help. In addition I have an in-house editor, Kate Whitfield, who is also a great help to me.

K: In the Author’s Note for A Different Dog, you offer insights into the genesis of the story. How it started – or at least you think it started – with an unpleasant memory of burying your dog as an eight-year-old, but as the story developed it slowly metamorphosed into something completely different.

As someone who often makes up genesis stories for my own ideas, what I’d really like to know is – how much of it is true? Or is that giving away too much?

P: The story A Different Dog contains a lot of elements from my own experiences. I had a dog which I loved when I was a boy. My father didn’t like it and one day it disappeared. I’m pretty sure that I know what happened to it. I was devastated by this loss and it is a major part of the story. The boy has a speech problem and it just so happens that I was a speech pathologist for many years. I also witnessed a man drive over a cliff during a hailstorm. I had to climb down through the forest to find him, still alive but unable to move. I remember the dread of approaching that car and in the story I wrote just how I felt. Originally, it was going to be the dog that died but my instincts told me to make it the man who died and dog that lived.

These days I just follow my instincts through the story.

K: I particularly loved your latest stories – A Different Dog and A Different Boy. They were compelling and rather poignant, with twists that kept me guessing – wrongly, I must admit – right until the revelation. And when everything was revealed, it was intensely satisfying and entirely inevitable, in retrospect.

I found the poignancy especially fascinating. While your stories are always emotionally gratifying, poignancy seems to be something new. An extra layer generally not apparent in your earlier stories. At least not in the ones I’ve read. Interestingly, for me, both stories are also in third person.

Which makes me suspect the stories are somehow rather personal. You suggest A Different Dog is linked to the emotional impact of burying your own dog. And in A Different Boy, Anton, your orphan protagonist, stows away on a ship bound for a bright New Land, which seems to link back to your own experiences migrating to Australia when you were six.

So, after that rather long preamble, I guess what I’d really like to know is, firstly, how personal do you feel these stories are? And secondly, is there any reason for their unusual poignancy? Or am I totally over-analysing it?

P: When I first wrote I was responding to a community need. Publishers might call it a hole in the market. I was writing to fill a need for easy to read books with good stories that might attract the more reluctant readers as well as the competent ones.

I did realise that there were some very strong themes in my stories – loneliness, courage, being different, separation and loss, irrational fears, and good versus evil. But, as I said earlier, I didn’t start writing to a theme. I always let that emerge. Jung describes two types of writing – psychological writing, which aims to teach and inform, and unconscious writing, which lets the psyche speak. I don’t think it is always one or the other but rather a mix depending on the author. My plots are conscious, my themes emerge.

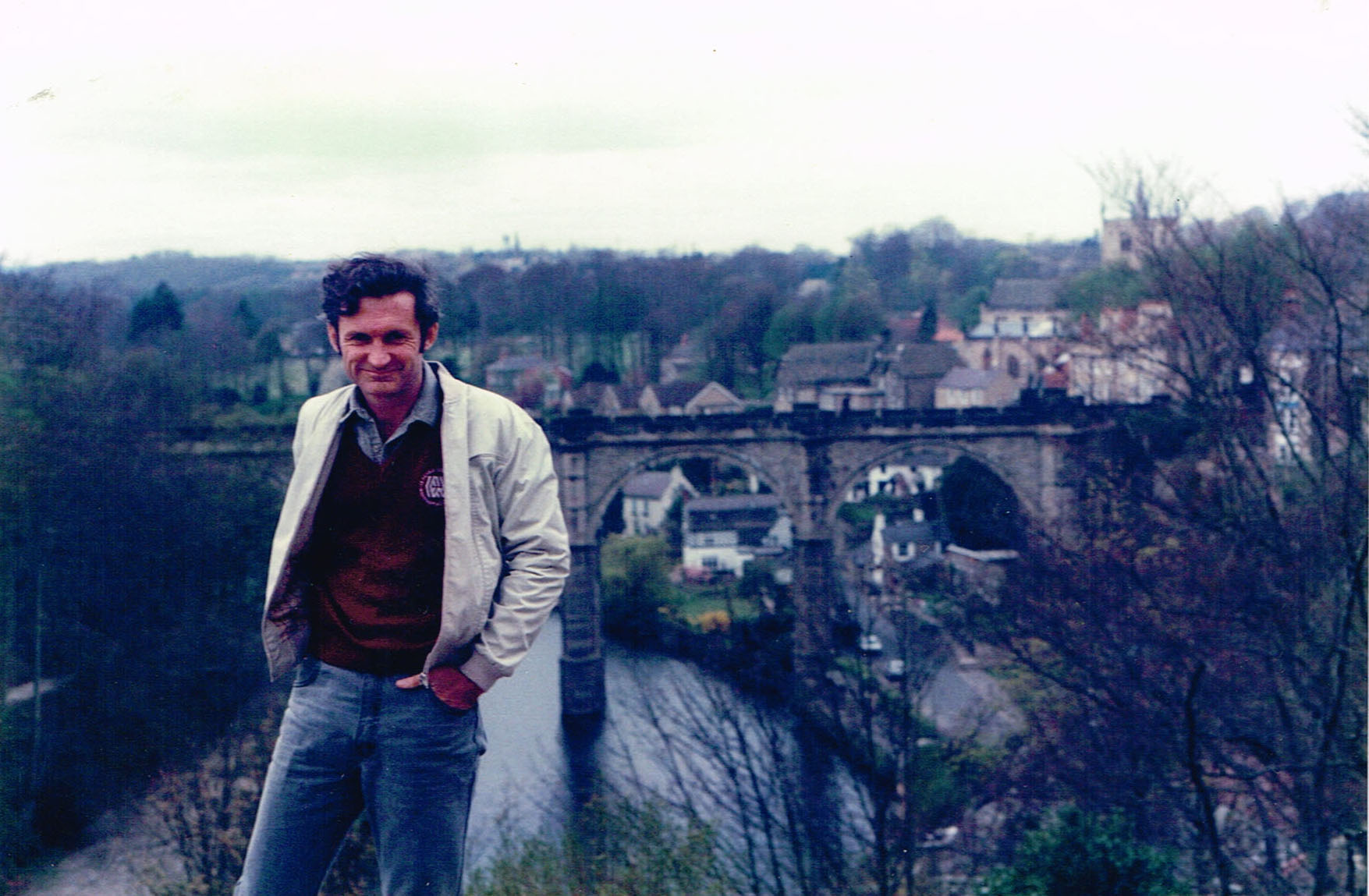

A Different Boy does call on my experiences as an immigrant. The trip is etched into my mind. In the week before we left England I had the same dream twice. I was tumbling down the stairs outside my tiny bedroom. At the bottom was a huge ocean with giant ships sailing around. Just before I hit the water I awoke trembling with fear. The night before we boarded the boat my grandmother dreamed that she died on the boat. She refused to come and we sailed without her.

The night before we boarded the boat my grandmother dreamed that she died on the boat. She refused to come and we sailed without her.

This story also has some of my adult experiences in it. Wolfdog Hall, the terrible juvenile training centre, was based on my experiences in such a place when I was a young teacher. The descriptions of the bombed-out buildings in Europe come directly from my parents’ mouths.

Yes, these two stories are different to my earlier work. Today I am responding to a different community need. Teachers, librarians and parents have told me that there is a need for easy-to-read stories at upper primary and lower secondary school level. Stories the readers can discuss and discover some human truths. Where they can ponder questions such as, ‘Did the death of the boy’s dog have anything to do with his speech problem?’ or ‘Do dogs think?’ or ‘Do we sometimes obey when we shouldn’t?’

I’m glad that you like these stories because I think that they are my best so far.

K: In two of your more recent titles – A Different Dog and The unforgettable what’s his name – your protagonist follows an abandoned railway track leading into a dark forest. Which kind of suggests your hero is taking a different path heading into the unknown. Does the motif have any personal meaning or link to some personal experience? Are there other motifs that have tended to pop up over your long career?

P: This is interesting question because I wasn’t aware that the two stories had abandoned railway lines. And even more interestingly my next book, A Different Land, also has one. Is this careless or is my unconscious mind at work here? A decaying railway line is certainly a great metaphor for a journey into the dark places in one’s own mind.

We did live close to a railway line when I was young and I found great comfort from its sound in the middle of the night when I thought that a murderer might be under my bed. And I did often put pennies on the railway line but of course I wouldn’t be allowed to put that in a book for children these days.

As far as unconscious motifs go, the main one I am aware of is the separation of the parent and the child. This is the strongest theme one can write about both for children and adults. I don’t do it deliberately – in fact I try not to do it but for some reason it always pops up. I did miss my grandmother terribly when we came to Australia. Maybe, unknown to me, I was re-working the terrors of leaving home. Particularly relevant at this time.

As far as unconscious motifs go the main one I am aware of is the separation of the parent and the child. This is the strongest theme one can write about both for children and adults.

K: Finally, as a writer who has had an extraordinarily long and successful career, what do you think are the key ingredients of a successful children’s story? And can you offer any words of wisdom or advice for aspiring children’s writers?

P: The main piece of advice I can give to emerging writers is to find what you are good at and go for it. When I was in Year 7, I received two bits of encouragement. The first one happened when the class was asked to write a piece of fiction. I was accused by the boy who sat next to me of stealing the story out of book. I was thrilled with that accusation –he actually thought that a published author had written the original.

The second encouraging incident happened when our history teacher held up one of my answers to a question. He said, ‘Jennings has answered the question just as well as anyone else in the class but he has only used half the number of words as the rest of you.’

I knew that I was good at precis. I could always cut a piece of writing down to its core. So, there it was, staring at me all those years ago. I could tell a good story and I could do it using a small number of words.

I only wish that it didn’t take me another 30 years to discover my talents.

Kyle Mewburn

Kyle Mewburn is one of New Zealand's most eclectic and prolific writers. From multi-layered picture books and laugh-out-loud junior fiction series; to short stories, novels and memoir; her titles have been translated into eighteen languages and won numerous awards including Children's Book of the Year. She was Children's Writer in Residence at Otago University in 2011 and President of NZSA from 2013–2017. Her most recent novel, Sewing Moonlight, is published by Bateman.