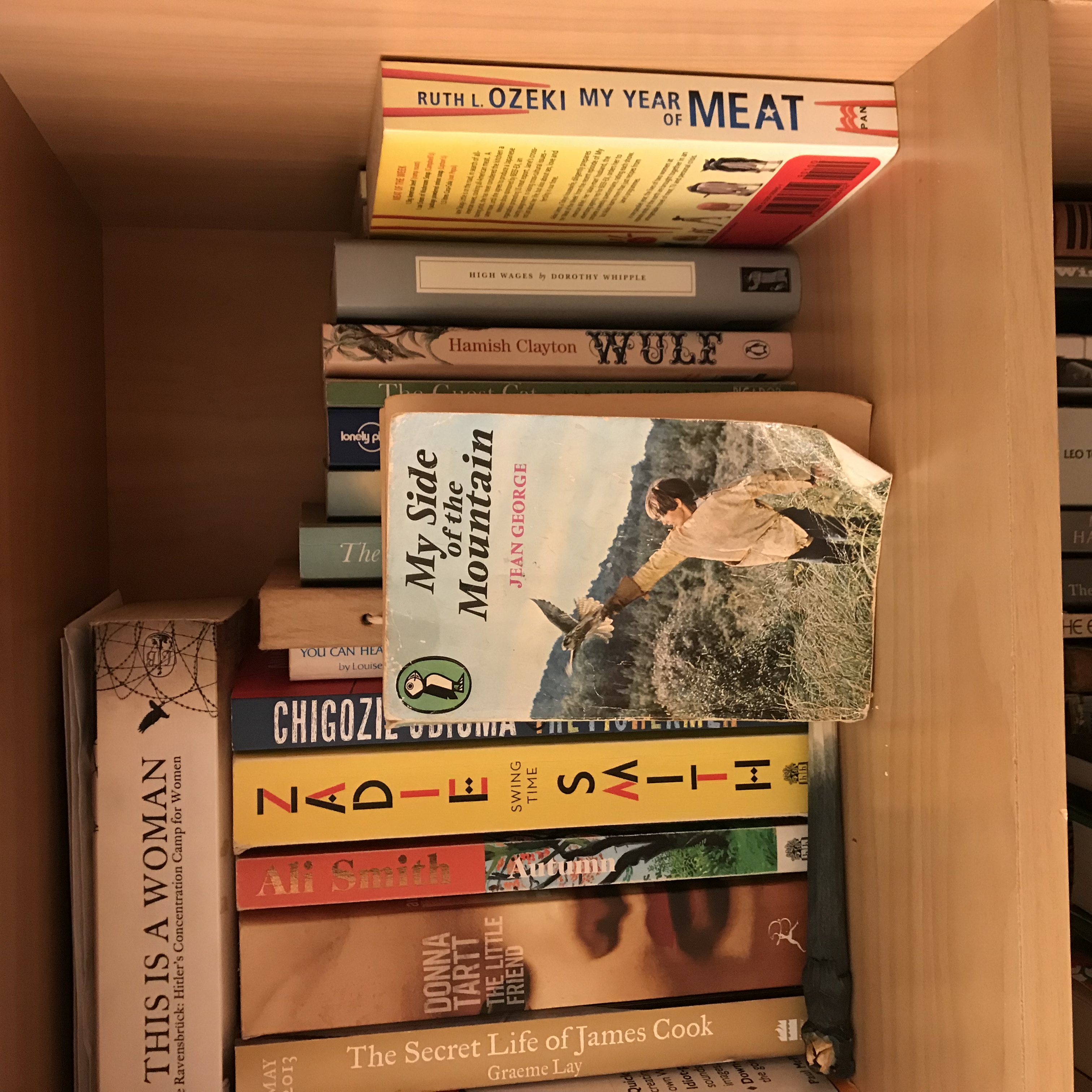

‘From where I sleep I can see the book on my bookshelf. I have read it so many times it has fallen apart, and now exists as an inelegant bundle of browning pages and brittle Sellotape.’

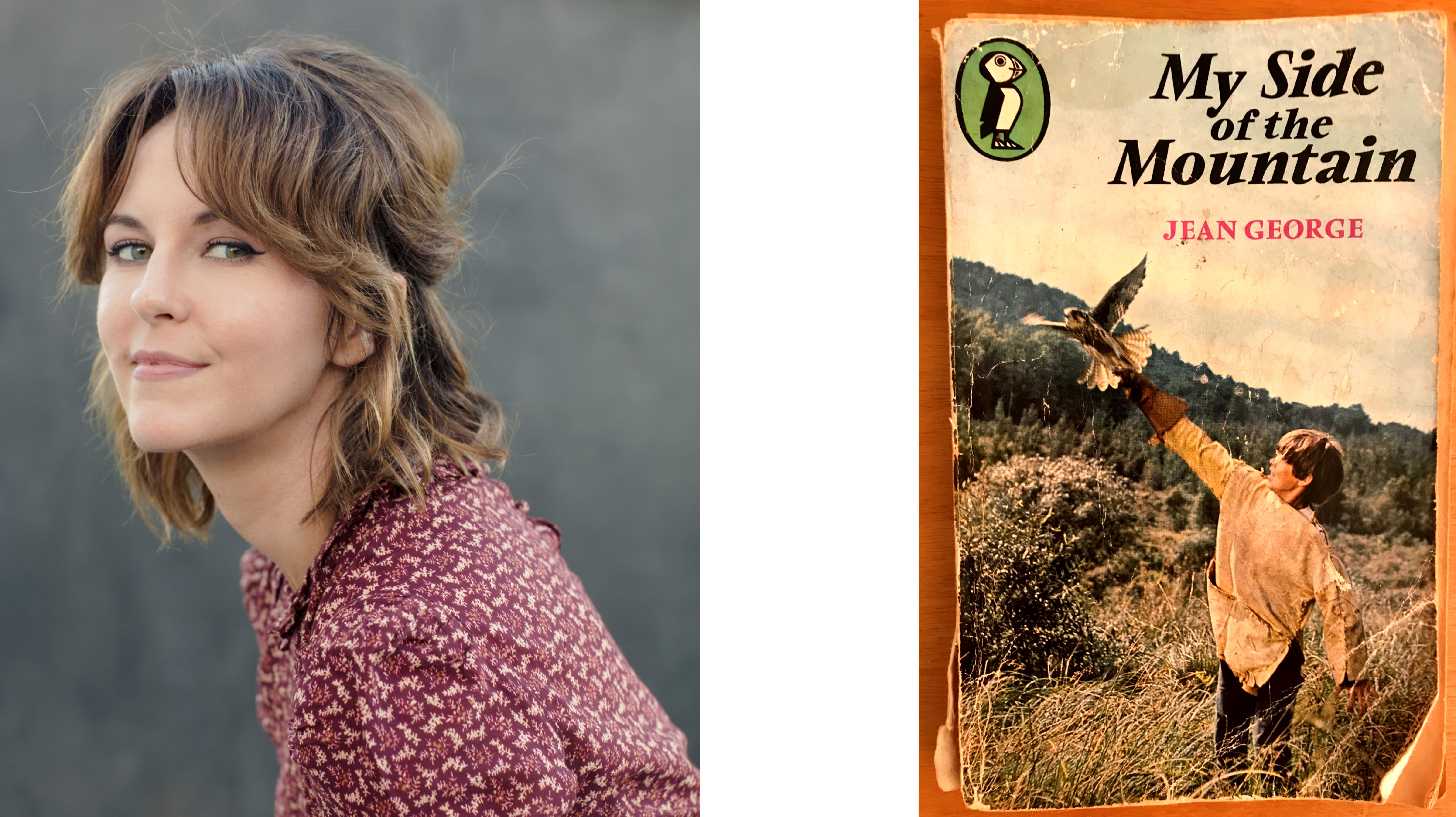

All her life, actor and writer Michelle Langstone has felt the influence of the 1959 novel My Side of The Mountain by Jean Craighead George, and here she explains why.

By the time I was 10 years old, I had run away three times. All three times I attempted to run away and hide in a tree. Two of the trees were in the garden of my own home, though far enough down the bank to be obscured from view of the house, and one was up the road in another person’s garden. If it sounds daft, well — that’s because it was. The least successful of these missions had me sitting in a young Gleditsia tree, perhaps about two feet above the ground, holding a backpack and eating a cheese roll for sustenance. I went home after the rest of the food (a Snack Log, an apple) ran out, which was approximately 45 minutes later. I am absolutely certain my running away was the fault of one book, and one book alone.

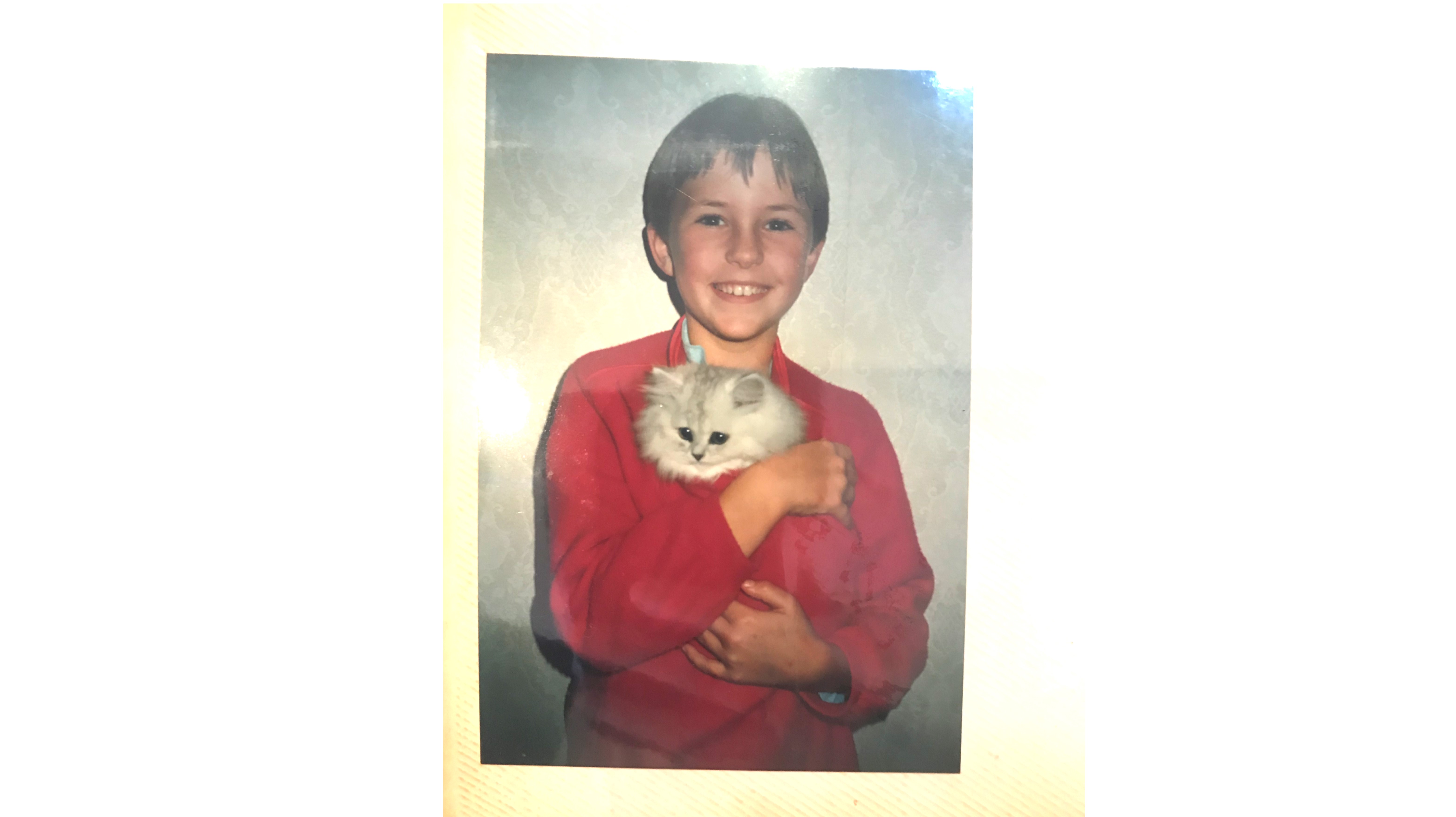

A battered copy of My Side of the Mountain by Jean Craighead George made its way to me via the bookshelf at a friend’s bach, in the summer of 1988. I was nine years old, and due to an unfortunate incident with our neighbourhood hairdresser, I had very short hair styled in a spike just like all the boys on my street. It was such a bad haircut that I refused to get my photo taken all year, and made a forced retreat into a space where only adventure mattered. I got about that summer in practical clothes — shorts, bare feet and old T-shirts — and it could be argued I was running a bit toward the wild. Over that long holiday season we kids only came in at mealtimes, and were scarce seen again until dark. I read the book in the narrow shade of the bach over two sunny afternoons. A week later, I ran away.

My Side of the Mountain concerns a boy named Sam Gribley from New York, who runs away to the Catskill mountains where his great-grandfather once lived off the land, and where legend has it a giant beech tree bears the Gribley name. Sam is a 14-year-old romantic at heart. He’s like a young Thoreau, and he longs for the wilderness and to be free in nature, attuned to the rhythms of life that come from isolation. He’s not running away because of troubles, he’s running away because the call of the wild has started echoing in his ears, and his family legacy occupies every space in his imagination. At its heart, My Side of the Mountain is an adventure story, but it’s also about connection: Sam discovers a loneliness that can only be filled with relationships — whether it be with a peregrine falcon, a naughty neighbouring weasel, or a librarian in the closest town.

He’s not running away because of troubles, he’s running away because the call of the wild has started echoing in his ears …

My Side of the Mountain was a great success when it came out — becoming a Newbery Honor book, then becoming a film — and later, George went on to win the Newbery Medal for Julie of the Wolves. George was the real deal: she studied science and literature at Penn State University, and went on to report for the Washington Post. After she had her children her focus shifted back to the environment, and when they were old enough, she and the kids went into the wild to observe animals and nature, then she’d come home and write about them. From what I can gather, George had a procession of wild animals tromping through her family home regularly, and that kinship and observation sparked the impulse for her stories.

My dad always said you need to keep three things on your person at all times — a pocket knife, a length of string, and a handkerchief.

My dad always said you need to keep three things on your person at all times — a pocket knife, a length of string, and a handkerchief. Sam Gribley had the first two, along with some flint and steel, and I took it as some kind of talisman that his possession of these meant he had been sent to me for a very important reason. In Sam Gribley I felt an allegiance; he didn’t have a very good haircut either.

Like many of the books I inhaled as a child (Gerald Durrell, James Herriot, Jane Goodall, Michaela Denis), the book is filled with finely detailed descriptions of animals and nature, lending an immediacy that allows your own world to vanish for as long as your nose is amongst the pages. Sam hollows and then burns out a gigantic old beech tree, and lives inside it, sleeping on a bed made of beech sapling, keeping warm with a small fireplace made from clay hauled from a riverbank, the drafts kept out by a deerskin-hide doorway. With the help of his falcon, he becomes an adept hunter and catches rabbits for his dinner. There are freshwater crayfish in the deep pools of rivers, there are tubers to be dug, weeds to be collected, and nuts to be roasted and ground into flour. It got under my skin, that way of life. Our family would be out on the boat, and I’d have a string line in the water, fishing for sprats with a bit of flour and water balled up as bait, and I’d think about Sam. When we struck matches to light mosquito coils, I’d remember Sam’s first miserable night on the mountain, trying to start a fire with flint and steel, and failing, and falling asleep cold and miserable. The matchbox seemed like cheating.

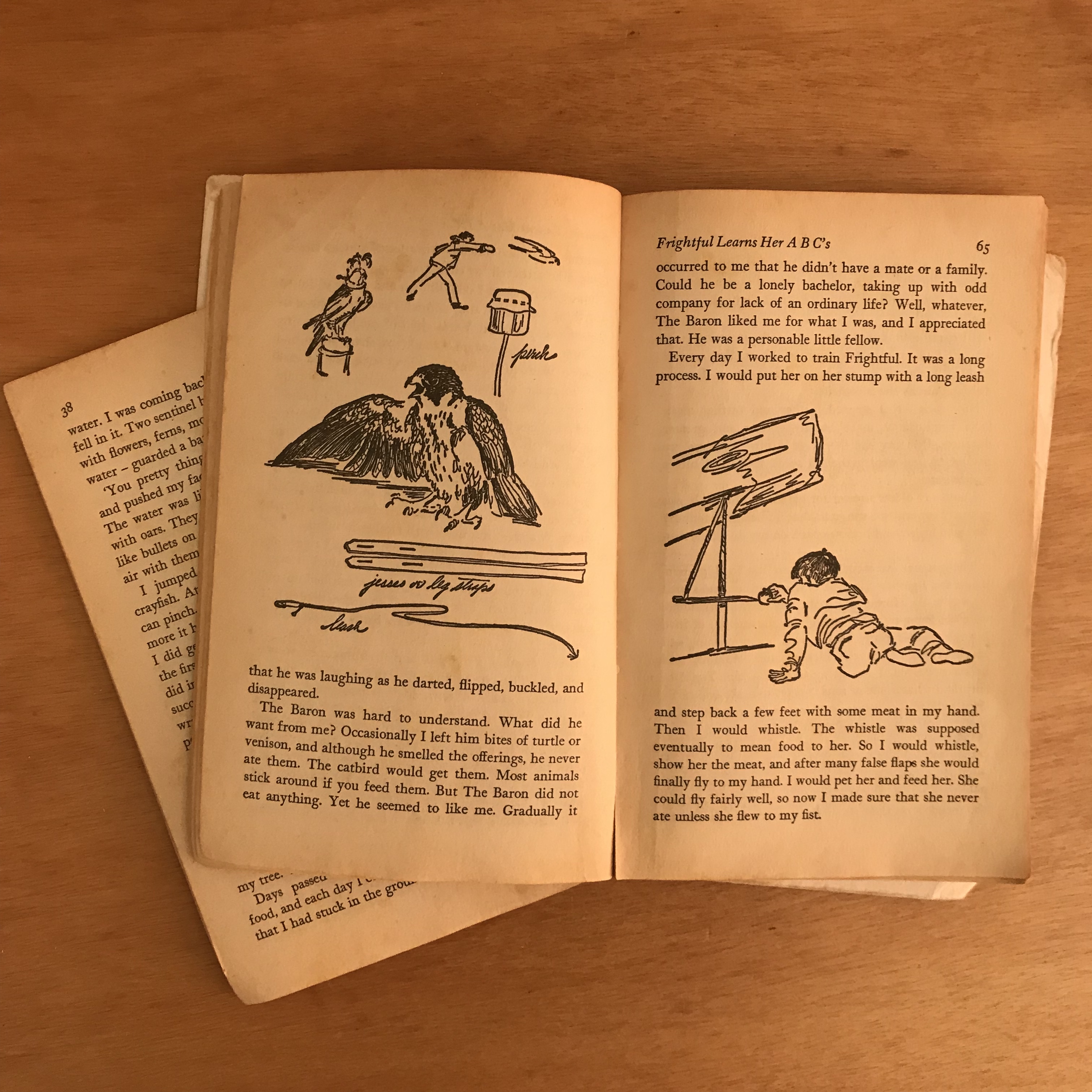

Accompanying the descriptions of the food Sam forages and cooks are rough sketches of plants, and of twigs and twine he fashions into hooks for fishing. I don’t know why I’m so obsessed with what people eat in adventure stories, but I am. I was fixated in Robinson Crusoe, in Swiss Family Robinson, and in Little House on the Prairie. George’s descriptions are vivid — the smell of fish cooking over a fire drifts from the pages and makes your mouth water. Sam’s recipe for a rudimentary berry jam that he smears on acorns pancakes still makes me ferociously hungry to think of.

It’s an ancient and oft-told story, and reflects what I believe to be a universal yearning in the human spirit — to be truly free.

In recent times, books like H is for Hawk by Helen McDonald have captured the grown-up public’s imagination in much the same way. In that book, McDonald writes about adopting a goshawk after the death of her father, and hand-rearing it. There is a common thread shared between that book and My Side of the Mountain, and it’s finding strength in returning to nature, facing yourself and your own wildness. It’s an ancient and oft-told story, and reflects what I believe to be a universal yearning in the human spirit — to be truly free. Sam steals a baby falcon from a nest, and names her Frightful, and hand-raises her to become his companion and hunting assistant. The relationship between boy and falcon from Frightful’s early, vulnerable start is one of deep reverence and consideration. Sam’s attunement her to her wilder nature is written with intimacy and respect. As Sam says to Frightful, when she has sensed a change in the environment far more swiftly than he, ‘You wild ones know’.

And they do know. All of the regular cast of animal species that appear in this book have an innate knowing and way of being that is uncomplicated and beautiful. Jean George doesn’t anthropomorphise the creatures we make acquaintance with — something I appreciate very much — but rather lets them come and go in Sam’s life as he happens across them. Those that become familiar with him and share his environment grow in their focus and distinction, and others, like the deer whose lives he takes, are fleeting visitors.

The books I love most are the ones that teach you about a greater wisdom we have forgotten in our very modern and busy technological lives.

The books I love most are the ones that teach you about a greater wisdom we have forgotten in our very modern and busy technological lives. The land and the ocean are always the answer. When I forget myself, it is invariably because I have forgotten to listen to the environment, and watch the weather and the creatures around me. In those times, when I am out of sync with the rhythm of my life, I run to stand barefoot in a forest, or submerge in a sea, and the world comes back to me as it truly is — unmasked from the burden of time and the requirements human existence.

The older I get, the closer I feel to Sam. From where I sleep I can see the book on my bookshelf. I have read it so many times it has fallen apart, and now exists as an inelegant bundle of browning pages and brittle Sellotape. Sometimes when I can’t sleep I imagine I am inside a tree, sleeping on a beech-slat bed, listening to the night sounds. I go camping a lot, just to only have one fine layer of nylon between myself and the night and the stars. I sit on the stairs at the edge of the garden and watch the insects. I listen for birds and make note of new songs. Down by the estuary, I lay on my stomach on the boardwalk and watch the crabs shuffling round on their errands when the tide is out.

The older I get, the more I remember to listen to the world around me that way that Sam does. I feel the urgency of the message of respect and reverence for all life that is in My Side of the Mountain. After a time of loss and grief, it is not in people, but in the land that I have found the most comfort. All life is there, humming in its busy routine. All death there too. Every cycle begins and ends in a second, a minute, an hour, a day, a month, a season. I find comfort there, in the natural way of things. I think about Sam out in the mountains alone with his bird, dressed head to toe in deerskin, watching the weather and planning accordingly. I watch the weather on an app on my phone, and imagine the scent of rain.

Michelle Langstone

Michelle Langstone is a writer and actor, who has written about literature and culture for North and South, The Spinoff, Radio New Zealand, and New Zealand Listener, and reviewed books on George FM. She is a contributor to Headlands, a collection of essays about anxiety, published by Victoria University Press.