essa may ranapiri (Ngāti Raukawa) recalls the commitment of their nan in reading The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings aloud, the significance of Mauao to their early life, and the poetry of Grover. essa’s debut poetry collection, ransack, is out this month from VUP.

My nan and I lived in a two-storey house not very far from the beach at Mount Maunganui. My nan would read me stories before bed. We had a lot of those gold-spined books featuring puppies and bears and other things (a quick Google search informs me that these books were called Little Golden Books, which makes sense).

The Monster at the End of this Book is one such book that clings to my memory like hot glue. If you haven’t read it, it’s a short picture book that features a truly distressed Grover, of Sesame Street fame, trying to stop the reader from turning the pages, in fear of the eponymous monster at the end. The way the book speaks directly to the reader echoes something that I find appealing about poetry: the way poetry can even shock and push the reader away like Grover does, yet paradoxically propelling the reader on. And there is something incredible in finding out the monster is in fact friendly Grover, and through the story he gains a new understanding of himself. The text is an object, and the pages are recognised as tactile elements of the story.

The text is an object, and the pages are recognised as tactile elements of the story.

This is something I try to accomplish in my poetry but in a very different form. In an early manuscript I had a message to the reader directly in the centre that said please stop reading. I owe a lot to Grover’s book.

A lot of what engaged me about books early on were the pictures. I have loved painting and drawing for most of my life. And I watched Disney films, my favourites being Mulan and Pocahontas. I spent a lot of time admiring the stills from Pocahontas reproduced in those big hardcover Disney picture books. I always loved the opening section, that long river, the waterfall and those many-coloured leaves. I remember having a particular affinity for Grandmother Willow; the idea of the living talking tree still resonates with me. I would often go out into the backyard and touch the plum tree and talk to it: are you sad the birds get at your fruit before they’re ripe? Do you want to move from your lonely spot in the backyard? And: I’m sorry for breaking your branches.

In primary school, my nan sat me up at the kitchen table and with a staggering level of commitment and time read aloud to me the some-thousand-and-something pages of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. At the start, I was excited to dive into a world that my nan had told me was a lot like Star Wars, but I think that excitement started to wane as we got through the endless descriptions of landscape and history and those long songs all rhyme and metre – no lightsabers here. I can’t remember if she ever finished it. If I were her I wouldn’t have continued reading to a kid lying down under the table playing with the wooden legs, but perhaps she did. In later years I eventually got lost in everything Tolkien, reading The Silmarillion to my bored family at Christmas. I guess they didn’t vibe with the faux-bible-history prose.

In later years I eventually got lost in everything Tolkien, reading The Silmarillion to my bored family at Christmas. I guess they didn’t vibe with the faux-bible-history prose.

Another story that has stuck with me, though I can’t trace it to any one book, is the story of Mauao, the maunga I grew up next to. The mountain, saddened by rejection, chose to cast themself off into the ocean. They were pulled along by the patupaiarehe who upon the rising of the sun fled – as they were creatures of the night. I think about this maunga often, this grief that hangs over Tauranga-Moana. We live on a land of want and loss, between the separation of two lovers. This couldn’t help but inform who I am and what I write. Often I feel that in-between space, that moment before a plunge – is where I try to stay in my poetry.

There is often this idea about transgender people that the transitioning is a short period of time, you save up for funds for whatever surgery and then come out the other end whatever gender you’re aiming for. But for a lot of people it isn’t, for me it isn’t; I wonder if Mauao would understand how I feel.

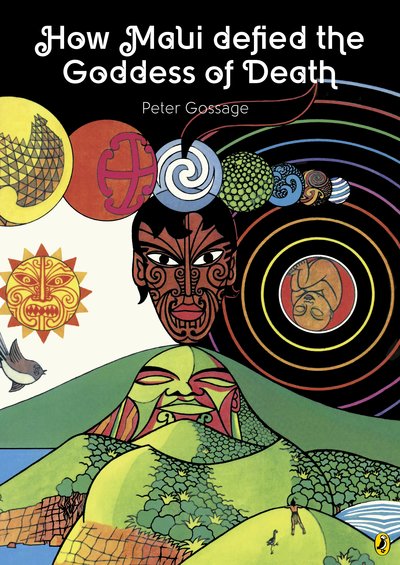

In intermediate I found a copy of How Maui Defied the Goddess of Death. We were told the stories of Māui all through primary school – Peter Gossage’s two dimensional representations of Māui and his adventures, his taming of the sun, his theft of fire, his fishing of Te-Ika-a-Māui – but were never told of how his tale came to an end. This stuck with me: Māui ends up stuck inside of Hine-nui-te-pō and upon her being wakened by a laughing pīwakawaka, he is crushed. The tragic hero dying an almost comedic death.

I often think it’s strange that that tale is told from Māui’s perspective when perhaps we get more out of seeing the events through Hine-nui-te-pō’s eyes. Out of any book from my childhood this has had the most impact on the work I write today. The last poem in my book ransack draws directly from this tale.

From children’s metafiction to high fantasy, from problematic Disney orientalism to Māori oral traditions reinterpreted in colour books, the world was opened in these pages and in some ways I’m still swimming through these words today.

essa may ranapiri

essa may ranapiri (Ngāti Raukawa) is a poet from Kirikiriroa, Aotearoa. They are part of the local writing group Puku.riri|Liv.id. Their work has appeared previously in Mayhem, Poetry NZ, Brief, Sport, Starling, Mimicry, THEM and POETRY Magazine. They graduated with an MA in Creative Writing from Victoria University of Wellington in 2018. They will write until they’re dead.