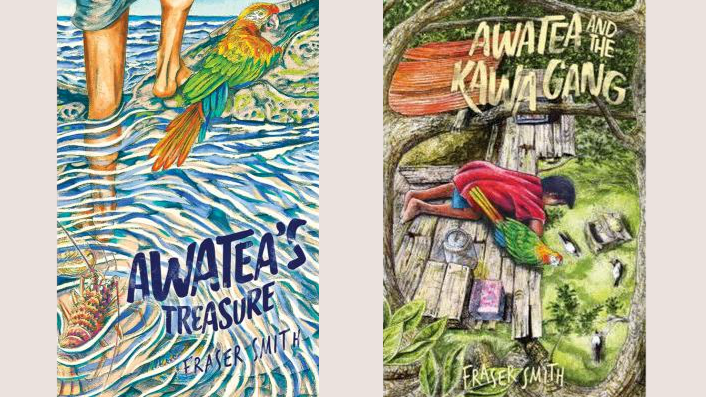

Many of our country’s magnificent writers also have different day jobs, and chief among them are the teachers – or in this case, the principal. Fraser Smith, principal of Oturu School and author of Awatea’s Treasure (and forthcoming Awatea and the Kawa Gang), provides his take on getting our tamariki reading.

I can remember the two people who hooked me into the language of storytelling. One was my father reading to us at night, the other was a teacher. They were both passionate about the stories they read.

For over 40 years, I have in turn been trying to hook children into stories and books. My own children were easy targets, especially at bedtime. I read to them as they grew, until slowly they drifted off to read to themselves with no further need of me.

As a teacher, I had a continual source of children to throw stories out to. I used all my skills as a performer, all my voices, music and trickery. Sometimes there were not many bites until I changed the bait, but something did the trick. A good teacher will do some homework: which bait to use, what are the conditions, when is bite time?

As a teacher, I had a continual source of children to throw stories out to. I used all my skills as a performer, all my voices, music and trickery.

When children are hooked, there is a transfixed look on their engaged faces as the images and emotions of the story become their own for each one of them. I love that sweet spot when I am reading aloud and nothing else exists; it is socially and emotionally precious.

My experience over the last 40 years is that children have become more and more difficult to engage. This is especially true for many emerging 7-to-12-year-old readers. Shorter attention spans demand more effort when you are reading to them. When reading themselves, they seem to prefer easy shorter reads, and they often don’t finish a book. I believe digital shifts in technology – especially over the last 15 years – have created huge competition with traditional formats.

However, if I sit that same class around a fire under the stars, somewhere nicely remote with no devices available, the magic returns with a song, and a story;. I can’t see their eyes, but I feel their attention pulling at me. The story grows like Pinocchio’s nose. The call of a morepork, possum, or kiwi, and the lapping of waves weave themselves into the growing plot in my head and a few strummed chords add to the pictures in the background. The wairua of the spiritual connection the kids have with this world, adds to the magic.

The wairua of the spiritual connection the kids have with this world, adds to the magic.

There is a limited number of books I am passionate enough about to read to these emerging readers, most of them by New Zealand authors. At my school we have a student population that is 98 percent Māori, and I need to work hard to hook them in. That’s why I started writing; now I am hooked on writing and I try to write read-aloud stories.

II have a group of six or seven boys who come to my office at 10:15 every morning. Their teacher wanted me to read to them from Awatea’s Treasure. Because the book was written for 9-to-12-year-olds, I wondered if the material was too advanced. This group at 6 and 7 years old, is much younger than my intended audience and there are no pictures. But we sit on the floor. We talk about life and Awatea’s story so far. I play and sing a song that sets the mood; and hook them into it. They remind me and their teachers to make space for this because they want to come back every day for more.

I guess my point is that these guys are reluctant readers and writers, but not reluctant talkers. They are Māori boys showing they understand concepts I thought were beyond them. Their personal stories are compared with those in the book, and we share them. This has become the high point of my day. I know it will go somewhere, and I am pleased there is a sequel that I can read them next. They are my best editors.

I have seen reluctant readers become eager writers with help. Using their own context and sharing the printed stories with others, they become readers too.

I have seen reluctant readers become eager writers with help. Using their own context and sharing the printed stories with others, they become readers too.

I believe the digital age has affected how engaged teachers themselves are in the process of teaching reading for enjoyment. Perhaps there was always a group of non-readers in the teaching profession. When I was a teacher I was always in my own classroom bubble; now I am a principal I have a more global view. In my experience, young teachers are reading much less.

Storytelling was a big part of traditional Māori life. It still works today. To a kid a book without pictures can seem to be a cold thing, and too much to figure out… especially a fat book. It may be chosen for its cover but never read beyond the first chapter. The digital world delivers fast rewards by comparison.

Bringing stories and books to life for kids today needs their input too: drama, song and dance, with lots of questions about what they know and understand. Hopefully a lot of inference is locked up in the story to be unlocked together. Our children are no longer silent captives in the classroom, they need passion and warmth to hook them into reading.

Bringing stories and books to life for kids today needs their input too: drama, song and dance, with lots of questions about what they know and understand.

I have unfinished business. With my next book due for launching in September, I am quietly simmering another in the back burner of my mind. The flavour will hopefully appeal to our New Zealand kids and the style will ask to be read aloud. Some of the most precious and engaging books I have read with kids have been written in this country, by our own people. At school I try to contextualise learning to give it as much meaning and room for exploration as possible; enjoying stories is part of this.

Awatea and the Kawa Gang

By Fraser Smith

Published by Huia Publishing

RRP: $25.00

Release date: 13 September 2019

Fraser Smith

Fraser Smith is principal of Oturu School in Kaitāia, a Green-Gold Enviroschool where the curriculum is delivered in a hands-on, practical way, supported by the community. The school has beehives, chickens, fruit trees, vegetable gardens and a registered kitchen. Fraser is a keen fisherman and sailor who knows how to live from the resources of the sea and the bush. He also writes stories and songs, and plays and sings in a band.