Children and young adults in Aotearoa are particularly attuned to natural disasters. In today’s book list, Miriam Hurst delves into disaster literature from here and other shaky, volatile places around our world.

Then Snufkin said slowly: “It would be awful if the earth exploded. It’s so beautiful.” -Tove Jansson, Comet in Moominland

One of the first books I remember reading is Tove Jansson’s Comet in Moominland, an exquisitely terrifying mix of cosiness and catastrophe. Visions of stars with tails send Moomintroll and his friends on an increasingly hazardous journey to the Lonely Mountains Observatory. There, the comet’s nature and exact time of arrival are confirmed, but they have only four days to get back home, as the world grows hotter, the seas dry up, and survival becomes increasingly unlikely…

The Moomins (and the earth) survive. The comet flicks its tail and disappears; the sea rolls back in. But the knowledge that the world is not always benign remains, for the readers as well as the characters. Nature is never entirely benevolent or predictable.

In real life, some years later, I walked into the foyer of the medical school at Christchurch Hospital at 12.51pm on Tuesday the 22nd of February, just as a 6.3 magnitude earthquake hit. If not an earthquake, it might have been a flood, a storm, a landslide, a bushfire, a volcanic eruption; Aotearoa New Zealand is not particularly tranquil.

Before I’d experienced a real disaster, I found fiction about disasters exciting and unnerving. I still do; although for some time I avoided fictional earthquakes, as my own memories got in the way of the story. Books about disasters implicitly ask the reader, “What would you do?” and give you the tools to answer that; not just by imparting knowledge, such as the significance of the sea drawing back after an earthquake, but by showing characters who are forced to grapple with these situations, and all their successes and failures. The books I’ve chosen here are those where, in addition to engrossing reads, I’ve found answers, empathy and characters who give me hope when the inevitable occurs.

Picture Books

New Zealand

“Tiger woke with a start… and a feeling of dread.”

Quaky Cat came out in the immediate aftermath of the 2010 September 7.1 Christchurch earthquake, and follows Tiger, a handsome ginger cat as he searches through the shattered city for his home. In the sequel, Quaky Cat Helps Out, Tiger offers support and help to his less fortunate cat friends, who’ve lost their homes, families, or mental stability, in the earthquakes. Bishop’s drawings are fabulous, with their glimpses of Christchurch landmarks and expressive cat faces, and Noonan keeps the focus on achieving security while acknowledging losses.

Elsewhere

Kimiko Kajikawa’s Tsunami! tells of a coastal Japanese village and Ojiisan, its oldest and wealthiest inhabitant, whose unease leads him to watch the village rice ceremony from higher ground rather than attend.

When an earthquake happens – long and slow, but with no apparent damage to the village – he is the only one who remembers what that means (as do all the children reading familiar with the NZ Civil Defence warning: “Long or strong, get gone,”) and unhesitatingly sets fire to his ripened rice fields, letting them burn until all the villagers come up to help put them out – thus ensuring the people’s safety from the monstrous oncoming wave. Based on the true story of Hamaguchi Goryo and illustrated collage-style by Caldecott-winning illustrator Ed Young, it’s an effective and moving story about survival, community and sacrifice.

Jackie French and Bruce Whatley, the Australian writer/illustrator dream team responsible for the Wombat and Shaggy Gully picture book series, also have a series on Australian natural disasters. Flood (2011) is based on the 2011 Queensland floods and Cyclone (2016) on Cyclone Tracy hitting Darwin in 1974; Fire (2014) and Drought (2018) allude to particular events (the koala being given water by a fireman) without being confined to them, and sadly with climate change these events are becoming all too frequent.

French’s text is sparse and evocative: “A crack, a lurch, our house is torn/Ripped to paper by the storm” (Cyclone). Whatley’s art is equally good at drawing the viewer into the story; in Fire, he uses the white of the unmarked page to represent the livid heart of the flames, thrown into stark contrast by the surrounding smoke and ash. The books finish on notes of optimism – towns will rebuild, people will help, these things happen but there is an end.

The House on the Mountain, written by Ella Holcombe and illustrated by David Cox, tells of a family who lose their house to bushfire. There’s not a lot on the actual fire – “The drive down the mountain hides away in the back of my memories” accompanies a double page spread that is more terrifying with what it implies than what it shows – but in addition to glimpses of an idyllic bush childhood before, this book shows their slow rebuilding afterwards, as a family and as a community.

Holcombe, who lost her parents, her home and her dog in the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires says simply, in her note at the end: “I wanted this story to be about more than loss. Because family and home are bigger than that.”

Middle grade

New Zealand

Although Maurice Gee blows up Rangitoto at the end of his classic Under the Mountain (an eruption entirely due, with a very grim justice, to Theo’s inability to hold on to his power stone) and Karen Healy wipes out half the North Island with an earthquake in her Guardian of the Dead, these invented catastrophes occupy little space on the page. New Zealand stories that focus explicitly on the experience of natural disasters all seem to use actual historical events.

Elsie Locke’s A Canoe in the Mist tells of the Tarawera eruption in 1886, making it the earliest historical event in this list. The main viewpoint characters are a Pākeha girl and her British friend, who see the mysterious canoe on their first ever trip to the incredible Pink and White Terraces but Sophia Hinerangi (Guide Sophia) has a crucial role, and Locke puts a lot of effort into describing both the Pākeha and Māori communities affected. Her descriptions of the eruption itself are disturbingly vivid – the volcanic mud, the rains of ash, the stink, and the survivors huddled together waiting in the howling darkness.

Scholastics’ My New Zealand Story series are fictionalised overviews of key historic events, told in diary form, and also cover Tarawera, in addition to the Napier and Christchurch earthquakes, the Tangiwai disaster, Cyclone Bola, and the Wahine storm (in addition to many non natural disaster events).

The need for the narrator to not just survive the disaster but be in a position to document it faithfully in the aftermath does undercut the immediacy of these stories, and at times they become a little too didactic in their attempt to educate today’s readers in the vocabulary and vagaries of the past.

David Hill’s Journey to Tangiwai stands out, with a skilful portrayal of a family and a community en route to disaster, each event inexorably building on the next. Peter’s hard-won first aid skills are what will win him a trip on the doomed train to Auckland to compete in the scouting National Finals, along with his terminally ill uncle, who is determined to take one final action to support his pacifist principles; what puts them in the place of disaster may also be what saves them.

Lyla: Through My Eyes, is Fleur Beale (and NZ’s) contribution to the Australian Through My Eyes: Natural Disaster Zones book series, again part of a broader series focusing primarily on children from regions of conflict.

Lyla is walking down High Street in the city when the 2011 6.1 Christchurch quake hits; her parents (a police woman and an ED nurse) are at work, the phone networks are down, and Lyla is rapidly separated from her friends when she stops to help an injured man. Eventually she finds her way back to her damaged home, which becomes a gathering point for her neighbours as they sort out food, water, and power, and wait – with increasing anxiety – for news of friends and family. The book follows Lyla through the immediate aftermath and into the beginnings of recovery, finishing about eight months after the quake.

It’s an excellent and believable portrait of achievement, fear and recovery, and it feels real, both as a story and as a reflection of my experience (camping out on friends’ floors, barbecues and pit toilets, thinking earthquake! when trucks rattle buildings, breaking through army cordons (ahem)). Lyla grows from her experiences and is damaged by them; the book makes it clear that these things will always be part of her, but she can – and will – deal with them.

Best-selling pony author Stacy Gregg’s The Thunderbolt Pony takes place in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 Kaikoura quake. OCD sufferer Evie rides her horse Gus 60-odd kilometres across country to meet the evacuation boat the Defence Force is sending to Kaikoura rather than leave Gus (and her cat Moxy and dog Jock) behind. Evie’s external journey mirrors her internal journey, with a well-handled structure that alternates between past and present, with a dash of Greek myth.

Australia

Australia is largely free of earthquakes but has produced a number of excellent middle grade books about bushfires. Ivan Southall’s Ash Road won the Children’s Book of the Year Award for Older Readers in 1966, and time fails to dim any of its impact.

Three teenage boys out camping in the outback accidentally start a fire; when the fire warning goes out, most of the adults who live along Ash Road head off to fight it. Left behind are an assortment of children and elderly adults, who make bad decisions from lack of knowledge or a disinclination to admit the danger, who are terrified, who try and fail to cope, who struggle on until – at the very last – they are driven together by the flames.

It’s a relentless and all too realistic nightmare of a book. In the final chapters Grandpa Tanner lowers his grandchild and a neighbour’s baby into the farm well, strapped into a chair and a basket and tied to the ends of clotheslines; then he pours a bucket of water over himself, clamps his pipe between his teeth, and waits in the face of the oncoming fire for the very last minute to slide a sheet of corrugated iron over the well, painted with ‘Children Here’.

That’s a scene that I suspect Morris Gleitzman is paying homage to in Now, his contemporary entry in his excellent Holocaust survivor series.

Felix, now retired, lives with his granddaughter Zelda in the Australian bush. Felix’s eightieth birthday celebrations cause him to struggle with his past, while Zelda is dealing with being bullied at school and her parents being overseas, and doesn’t understand why her attempts to help Felix are making him more upset. A bushfire brings devastation, but also a path for them all to find a way forward.

Gleitzman, as always, handles difficult topics with humour, kindness and understanding.

In 47 Degrees, published this year, 12 year-old Zeelie lives with her family and animals in a bush town near Melbourne; as the temperature soars one hot February, her brother breaks his arm and her mother takes him to hospital, leaving her phone behind in the rush. As fire warnings are issued, Zeelie’s father decides to stay and defend the house, and Zeelie stays with him; it’s a decision they both rapidly realise was the wrong one.

Author Justin D’Ath has an extensive backlist of action-adventure for children; this book, however, fictionalises his own experiences of the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires, and he gives Zeelie’s father not only his own mistakes but his NZ origin and an accent that comes out under stress (D’Ath moved to Australia from New Zealand in 1971). Zeelie is courageous, but neither she nor her father anticipate how rapidly things can change in emergencies, and how minor choices can have major consequences.

Those seeking more Australian fictional disasters should consider the indefatigable Colin Thiele, who produced two books about bushfires (Jodie’s Journey and February Dragon) as well as landslides (Landslide), flood (Flash Flood), and earthquakes (the Shatterbelt duology). However, where I’ve turned to next is the United States, with two books about another disaster becoming more common and more severe; hurricanes.

United States

In Ivy Aberdeen’s Letter to the World, by Ashley Herring Blake, Ivy, age 12, draws pictures of two girls holding hands in secret magical places, clues to feelings she keeps hidden from her busy family. Then a hurricane destroys their house, displacing everyone and making Ivy feel even more invisible – and, worse, someone has found her lost sketchbook, and is sending her mysterious messages from it.

Ivy’s relationships with her family and her developing same-sex crush are explored realistically and with sympathy; but, although Ivy feels alone at times, all the characters in this book grapple with identity and change, from the tornado to medical issues to the stress of new baby siblings. It’s a hopeful, caring book that doesn’t opt for easy answers.

Rodman Philbrick, author of the classic Freak the Mighty, wrote Zane and the Hurricane about Hurricane Katrina, and it’s the first book on this list where the natural disaster is matched by an equally disastrous response from the people and organisations who should have helped.

Zane, who has mixed race heritage, travels to New Orleans with his dog Bandit to meet a relative of the father who died before he was born; while attempting to evacuate in advance of Katrina he and Bandit get left behind. After the storm he’s rescued by an elderly musician and a young girl, Malvina, both African Americans, and together they try to find a way out of the city.

But Malvina’s mother is in rehab for drug addiction, and at the first shelter they find, her mother’s dealer tries to snatch Malvina to use as leverage to stop her mother informing on him; when they escape and see a descending helicopter that they think might help them, it’s carrying a trigger-happy private security force concerned only with retrieving some valuable carpets. And when they finally make it to the Crescent City bridge, the police fire on them. The ending is optimistic, perhaps unrealistically so; but the overall impression it leaves of the fatal intersections of racism, neglect, and a belief that people should help themselves is depressingly realistic.

Young Adult

When natural disasters show up in YA fiction it usually heralds the end of the world, or at least a grim, dystopian, post-apocalyptic future and either the collapse of civilisation or a dubious cult with a lot of prescribed social roles. I think these disasters are easier than those in the middle grade books, for the characters as well as the readers; there’s a reassuring freedom to knowing that everyone’s doomed and everything is up for grabs that is absent from more local catastrophes. But if you start with the end of the world it’s hard to come up with a neat conclusion, and all of these books suffer somewhat on that front.

Ashfall, the first in Mike Mullin’s trilogy of the same name, starts with a very big bang – the eruption of the Yellowstone supervolcano, which sends molten volcanic debris into sixteen year-old Alex’s house nearly a thousand miles away.

Alex takes refuge with his neighbours, but after two days of constant explosions a bunch of armed looters break in, gunfire is exchanged, and Alex runs. Civilisation collapses rapidly with the exhaustion of food supplies; by chapter 16 there’s cannibalism and by chapter 27, a little under halfway through, Alex, conveniently a black belt in tae kwon do, is forced to kill in self-defence (content warning; in addition to multiple murders, one of Alex’s temporary companions is raped). He eventually finds a permanent travel companion, Darla, a skilled mechanic with farming experience, and the two of them set out to reach Alex’s family at a distant relative’s house, which although an arduous journey does allow enough time for them to begin a relationship en route.

Again, organised responses to the disaster are substandard at best, and while some individuals can be trusted, self-reliance is prized. It’s a trope I’m not at ease with, even while it makes for a compelling read.

Life as We Knew It, the first in Susan Beth Pfeffer’s Last Survivors series, wipes out even more people, after an asteroid strike that pushes the moon closer to Earth triggers a cataclysmic series of volcanic eruptions and tsunamis.

The story is told in fifteen-year-old Miranda’s diary entries, from her everyday life before the collision to the slow recognition of the scale of the disaster.

Unusually for post-apocalyptic fiction, she and her family stay where they are rather than travel; food runs out, the winter (exacerbated by volcanic ash) sets in, and everything they’ve known slowly shuts down (“I guess I always felt even if the world came to an end, McDonald’s would still be open”, Miranda writes).

Miranda’s prickly relationship with her mother is particularly well-drawn. It’s a book about holding on, rather than fighting back, and for that I like it more than Ashfall. There are three sequels; the first retells the impact from another point of view before the second returns to Miranda, but it’s the first that works best for me.

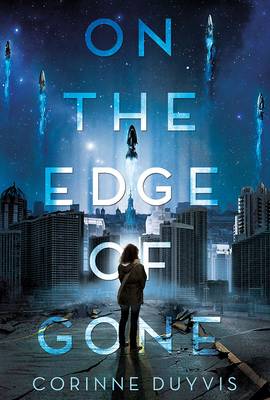

And back, at the end, to comets. At the start of Corinne Duyvis’ On the Edge of Gone Denise, a biracial teenager with autism who volunteers at a cat rescue, has forty-one minutes to get herself and her mother (a happy-go-lucky drug addict who wants to wait for Denise’s missing transgender sister, Iris) to their assigned temporary shelter in Amsterdam, before a massive comet hits. Everyone who could has either left for an Earth-like planet on a generation ship or gone to a permanent shelter underground. Stopping to help one of Denise’s teachers gets them entry on to a generation ship that is not yet ready to leave; but they can only stay for two days, and after that they’ll be on their own. The generation ship’s captain only wants skilled, valuable individuals.

Denise is a compelling narrator, and her attempts to find some way to stay on the ship keep the book going. It’s a book very much conscious of diversity and inclusion – and what could be more relevant to that than a situation where decisions need to be made as to who survives? – and the European setting and author give a different take on communities and disasters from the other two YA entries, both American. The ending is less convincing than the set-up, but the questions the situation raises stay with me.

Comets, at least, come with some warning. Many disasters – natural, personal, large or small – don’t. It’s an uncomfortable realisation. Fiction offers us a safer space to deal with this even as it points out the inevitability; and, always, holds out hope for something after. I moved out of Christchurch a little over a year after the February quake; I go back regularly, in person and in memory, working through my own story.

As Lyla’s counsellor tells her in Fleur Beale’s book: “The world isn’t a safe place. How about we talk about ways you can live with that?”

Miriam Hurst

Miriam Hurst is a medical specialist living in Auckland with five-year-old twins. She is currently updating her emergency supply kit.