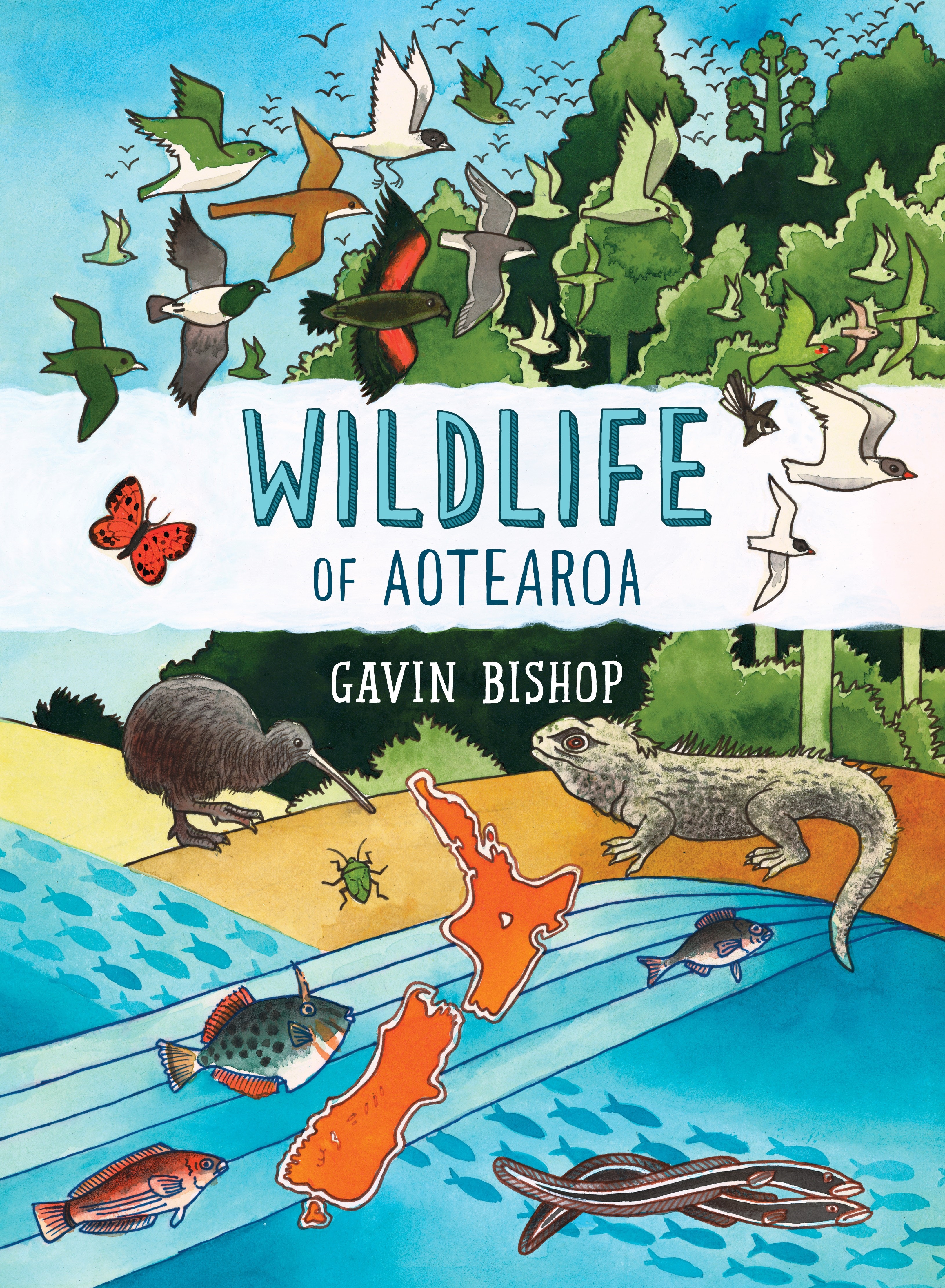

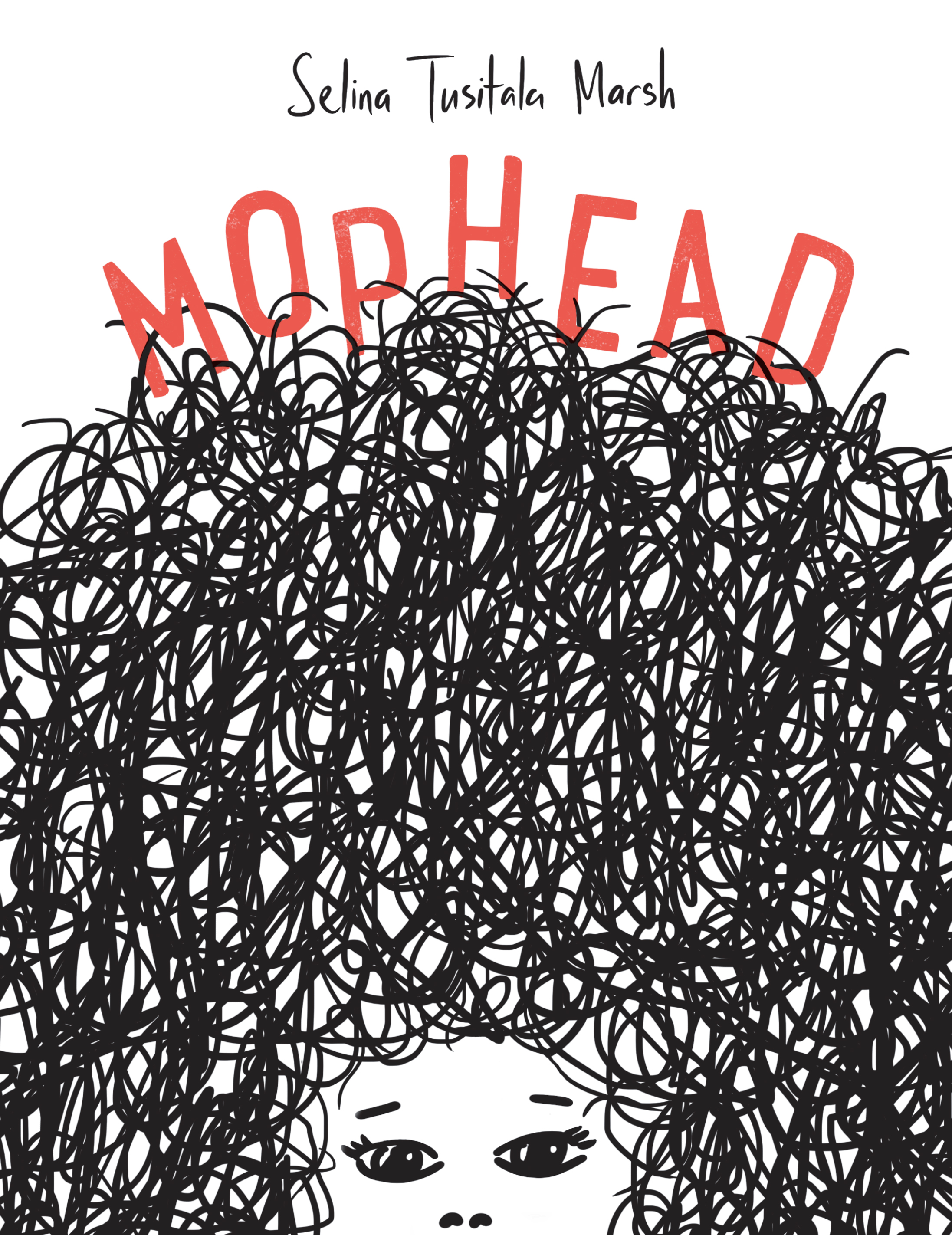

Last year two incredible books fell into our laps from titans of the New Zealand literary scene. Both have been recognised nationally and internationally as top talents, so naturally we wanted to see the magic of their two brilliant brains in conversation. We are very excited to have caught former Poet Laureate and creator of 2019 graphic memoir Mophead, Selina Tusitala Marsh, having a chat with 2019 Prime Minister’s Literary Award winner and author and illustrator of dozens of children’s books, Gavin Bishop. And now you get to read it.

Selina: How do you make sure the making remains central?

Gavin: I work at it like a job. I start around 9am after a cup of tea and a smoothie, and work through most of the day. I’m just starting a new book at the moment and I’m not going to tell you what it is because I don’t believe in telling people about things when they are just ideas.

S: See, that’s where we differ. I put the idea out as early as possible in a public space so they can help bring it to fruition. I need the pressure of expectation that something is coming so I’d better do it. But that might be reflective of the fact I have a full time job at uni, and I’m a researcher, so I need to use all the tricks of the trade to make sure the making stays central.

G: It puts the pressure on you to finish it.

S: It becomes a thing. A certainty. Because of all the doubt. Who am I to do this? Do I fit in this space? Actually I talked to Sam [Elworthy, publisher at Auckland University Press] about this yesterday and the phrase that’s been going around about Mophead is ‘genre-busting’. Which I kinda like because it entails punching and kicking and making space.

G: Yeah. This is my job – most of my time is taken up with writing and illustrating books.

The phrase that’s been going around about Mophead is ‘genre-busting’. Which I kinda like because it entails punching and kicking and making space.

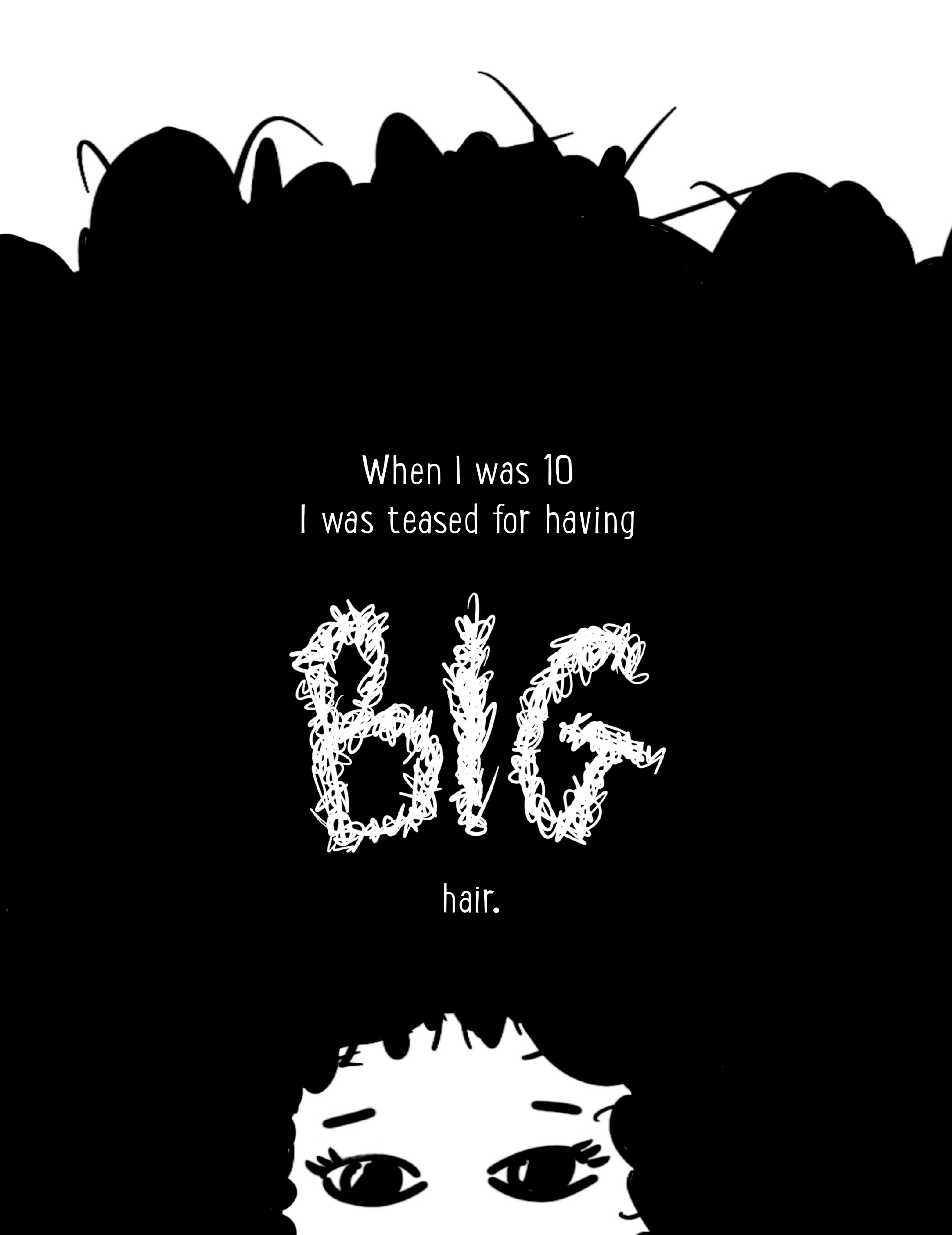

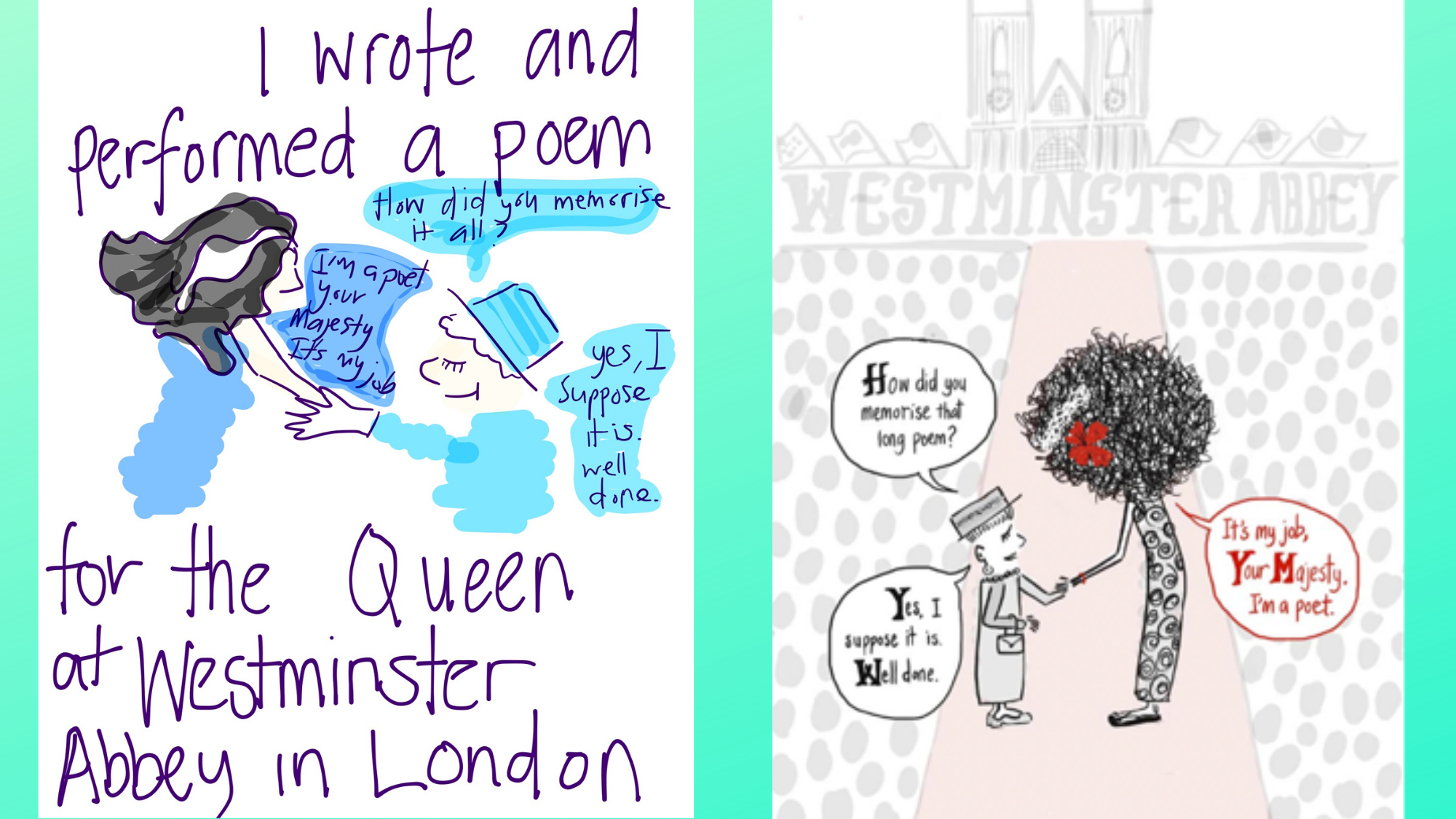

S: In one of our early communications, I did this self-effacing thing and called my drawings doodlings. And you came back and said ‘these aren’t doodles. They’re too resolved for doodles’.

G: A doodle is something that’s nothing, something on the edge of the paper while you’re listening to a lecture or thinking of something else. That’s a doodle. These are drawings with a purpose. They help to tell the story. They’re not doodles.

S: Vida Kelly was the layout designer, and I never met her, but she’s amazing. And it occurred to me that this isn’t too dissimilar to writing poetry and choosing where to put the gaps and spaces for breath. In between words and lines.

G: It all comes back to storytelling. When you tell a story, you pause, you take gaps, you pace yourself. They’re all devices to help the story to progress. And that’s what I like to think I’m doing in a picture book: I’m telling a story using the words, the pictures and the spaces. And pages where there’s nothing. That’s all part of the storytelling process.

That’s why I said that your book is not a collection of doodles. It’s all carefully considered and pieces are put into place to create a rhythm, a pace, a progression through the book. I always think of my work as being a whole thing. For example, I don’t like plucking one picture out of a book and putting it on a wall, because it gives you a false impression of the job that an illustration has. It is there to help tell a story. And all the illustrations hold hands with one another.

I don’t like plucking one picture out of a book and putting it on a wall, because it gives you a false impression of the job that an illustration has. It is there to help tell a story.

And you’re right about Vida – and Luke, her husband – I’ve worked with both of them. I’ve been very lucky at my age to have found someone who can take my work into new territories. Vida comes back to me with little suggestions and it’s a revelation.

S: In the initial conversation with Sam when I showed him the drawings, he loved them and said, one conversation we will have is whether you illustrate it or we contract a professional illustrator. I knew in my gut that my drawings were central to this story’s integrity and central message: if I can do it, you can too. The other message is: mistakes are made for making. I said it would feel disingenuous for me to have those kinds of messages then hand the creative process over to someone else. Vida enhanced my style, which I loved. She helped me visually convey its elemental storytelling features.In my initial meeting with Sam I had two possible books – one was the 60000-word poetic memoir about being poet laureate and the second was this crazy Mophead thing.

G: Probably the more interesting of the two.

*laughter*

S: Sam said that Mophead’s time has come. I haven’t just walked off the street, made my book and expected it to be published. It’s come after I’ve had the laureateship, after refining these stories, after realising in my own life that going wild is a way of being, so why the hell not do my own illustrations? It’s part of the zeitgeist.

I haven’t just walked off the street, made my book and expected it to be published. It’s come after I’ve had the laureateship, after refining these stories . . .

G: You’re right. And I’m in a similar situation. I’ve written two relatively long books for children. But they haven’t been taken very seriously because I’m not supposed to do that. Teddy One-Eye is 200 pages long. It’s got pictures in it, but it’s essentially a book of text. When it was published I got the sense that people thought that that wasn’t what I was meant to be doing because I was a picture book writer.

S: There’s something you said about Vida, that she took your work in a different direction. If we don’t take our work in different directions, if we succumb to a formula, that’s not going to work either. I thought I knew what the second Mophead was going to be about, but I was surprised at what came out so quickly when I woke early one Saturday morning and storyboarded the whole thing in one sitting…or should I say lying (down in bed!)

G: It was all sitting there in your head.

S: I saw the end point. It was when I had performed the poem for Harry and Megan’s visit to New Zealand. And I was in conversation with Harry and I showed him the tokotoko – the room was really noisy and everyone was starstruck with Megan – and the room was bubbling. Then there was this weird pause in unison, just as I raised my voice and said to Harry ‘would you like to touch my tokotoko?’ And there was an odd point where he was confused so I shook it at him and he said ‘oh, of course,’ then he grabs it and stamps it on the ground and says, ‘you shall not pass,’ from Lord of the Rings.

Then there was this weird pause in unison, just as I raised my voice and said to Harry ‘would you like to touch my tokotoko?’

G: Good heavens.

S: And that line went deeper for people of colour, indigenous, black, and into the notion of passing (a history of blacks pressured into passing for white), breaking the glass ceiling in terms of race. And Megan saying later she was proud to be the first royal of colour to visit South Africa. All these passing moments, suddenly they rose to the surface in the second Mophead, that’s what it’s about. It’s deep, but now I have to pull it back to its simplicity. It’s all in the simple lines.

S: So you’re an old hand at illustration and I’ve just recently given it a go. But you’ve always been a writer/illustrator haven’t you? What came first?

G: I studied painting at the Canterbury School of Fine Arts for four years, so I thought I was going to be a painter. But out of the blue, I met a fellow art teacher in Dunedin back in 1978 and she told me her son worked for Oxford University Press in Wellington, and they were looking for material to publish for children that had a strong New Zealand flavour. She asked if I’d ever thought of writing something for children, and I said ‘well, it’s weird that you should say that because it’s exactly what I’ve always wanted to do but I’ve never quite known how to get started.’

A strong New Zealand flavour, that was the thrust. So I thought, I’ll write a story about a sheep. And that’s what I did. I had no idea what I was doing, so I just wrote, wrote, wrote. It was overwritten, it was far too long.

A strong New Zealand flavour, that was the thrust. So I thought, I’ll write a story about a sheep. And that’s what I did. I had no idea what I was doing, so I just wrote, wrote, wrote.

Then, when I didn’t know what else to do with the text, I stopped and started doing some illustrations. A friend of mine typed up the story, and when she gave it back she said ‘you might find it’s a bit shorter than it was, because I left some bits out that I didn’t like very much’.

*laughs*

So I sent the whole thing to OUP. They said it was a bit rough but they would like to work on it with me. That’s when my apprenticeship started under Wendy Harrex, the editor. I was very, very lucky, because in those days, editors had the time and they weren’t so concerned with making a big profit. They were more interested in producing literature, rather than commercial products.

S: It has to be both, now.

G: But forty years ago, people published books because they thought they were important. It was different.

S: I’m really interested in the phrase ‘I didn’t know what I was doing’.

*laughs*

G: That’s the best way to start. I knew in the back of my mind that I would find out what to do by actually physically doing it. I am not great at solving things mentally; I am much better when I actually do something with my hands and solve problems like that.

S: I didn’t know I had Mophead in me, but as soon as I began drawing her hair, I knew she’d been waiting a long time to come out. As a child I always tried to make my own books with butcher’s paper that mum brought home. I’d fold them up and I’d do my own story and the illustrations. The challenge was finishing something, or being satisfied with something enough to bring it to completion.

Mophead is the first illustrated story that I’ve ever finished. So it feels amazing to be able to do that, but also have it carry a number of messages that I wish I’d heard earlier.

G: But I’m sure you feel like me too, that when you do finish something and it’s gone as far as you can take it, it’s time to get onto the next one. I always think the next book is going to be a lot better. That’s how I work.

I rely on my subconscious a lot. I get to the point with a story where I have no idea where it’s going. I have learned to forget it, go mow the lawns, let my subconscious work away on the problem and present a solution later on.

S: I think that’s more of a challenge nowadays when people are always ON… I often struggle to even find the ‘off’ button.

Being laureate was a lot of work, but it was work that I wanted to do. What the laureateship did was give me weight and legitimacy at Uni (the University of Auckland) to do exactly what I was doing before. Mainly outreaching to schools and community groups about poetry. And being an accessible portal for people to feel confident that they had their own stories and that they could write them. Recently, I was inducted into the Royal Society as a fellow for my research and creative writing. My first response was ‘how will this be of use to my community?’

Being laureate was a lot of work, but it was work that I wanted to do… being an accessible portal for people to feel confident that they had their own stories and that they could write them.

Uni was really happy with this recognition, but I kept thinking, ‘how might this help?’ Those letters behind your name, they actually count for something in particular contexts, and if it enables me to carry on doing my work, prioritising the making and the taking of stuff out there, then that’s all for the good. But I’m constantly struggling to not be consumed by institutional demands and needs and other people’s demands and needs.

Over the years, how did you stay focused on what was important to you?

G: I was a high school teacher for thirty years. A good chunk of those, I was writing. And I used to write at night after the kids went to bed for a couple of hours. Or I would wait for the Christmas holidays, and work like a lunatic.

S: What’s your working process?

G: I get all my ideas down on paper very quickly, then I go back and redraw them, sometimes using tracing paper. Next I make a dummy that has the same number of pages that the final book is going to have. I draw in pencil and glue the text into place on each page. I’m constantly thinking about where the words are going to go, and how they relate to the images on the page – how one page is going to relate to the next. And you do a digital thing?

S: I do a digital thing. I use an app called Procreate with a digital pencil. There are layers of images you can create that are effectively like tracing. You can put in a previously drawn page, like the Mophead character looking at something, then I can draw over it on a new page, trace over her hair, mouth, nose. It was incredibly helpful to discover that tool. But I also found these shortcuts took the edge off the rawness of freehand drawing. When I began copying and pasting Mophead’s hair, everyone around the editorial table preferred the fresh drawings.

My concern was with making her recognisably her over seventy pages. It’s that tension between ensuring continuity and ensuring freshness on the page.

My concern was with making her recognisably her over seventy pages. It’s that tension between ensuring continuity and ensuring freshness on the page.

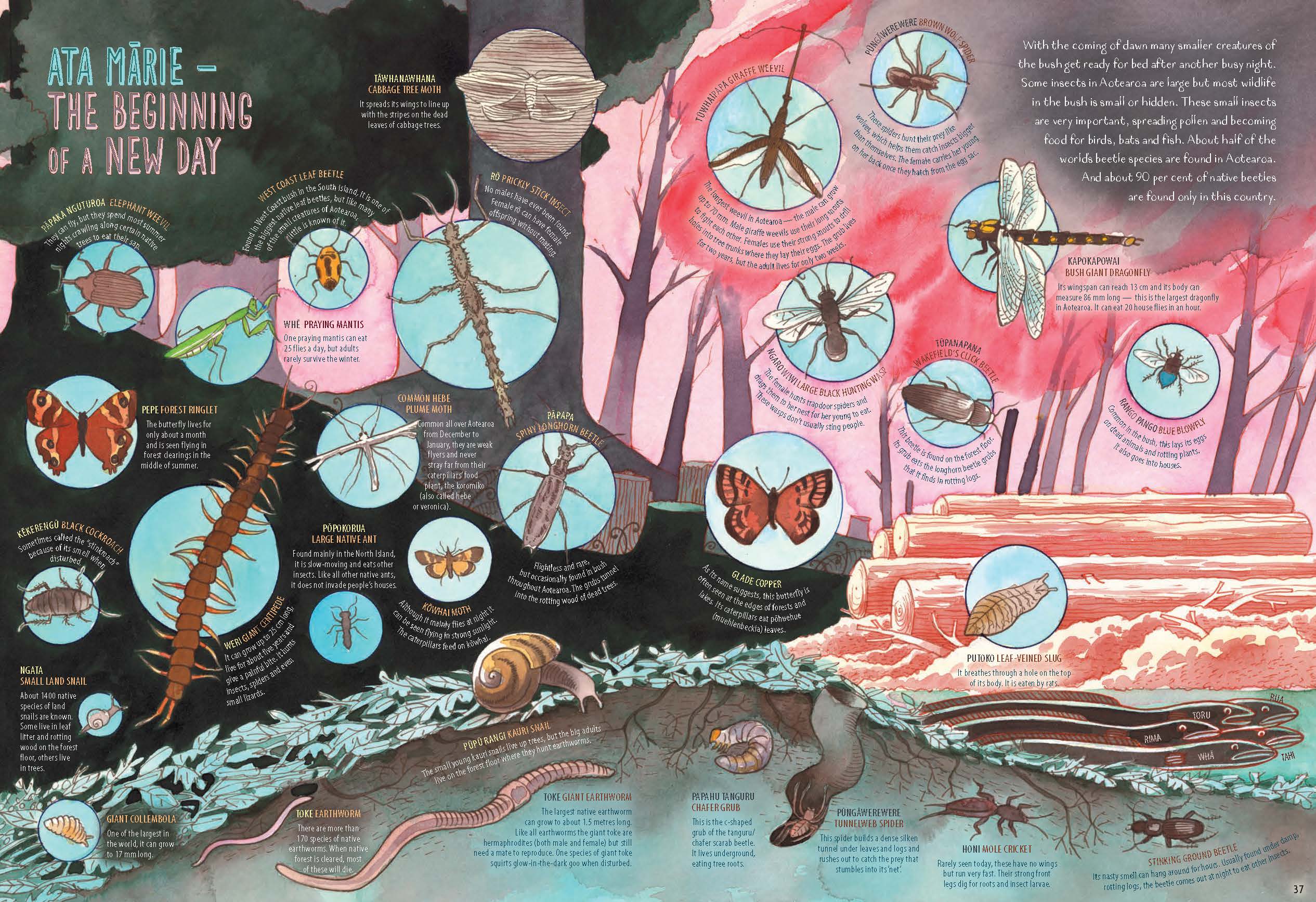

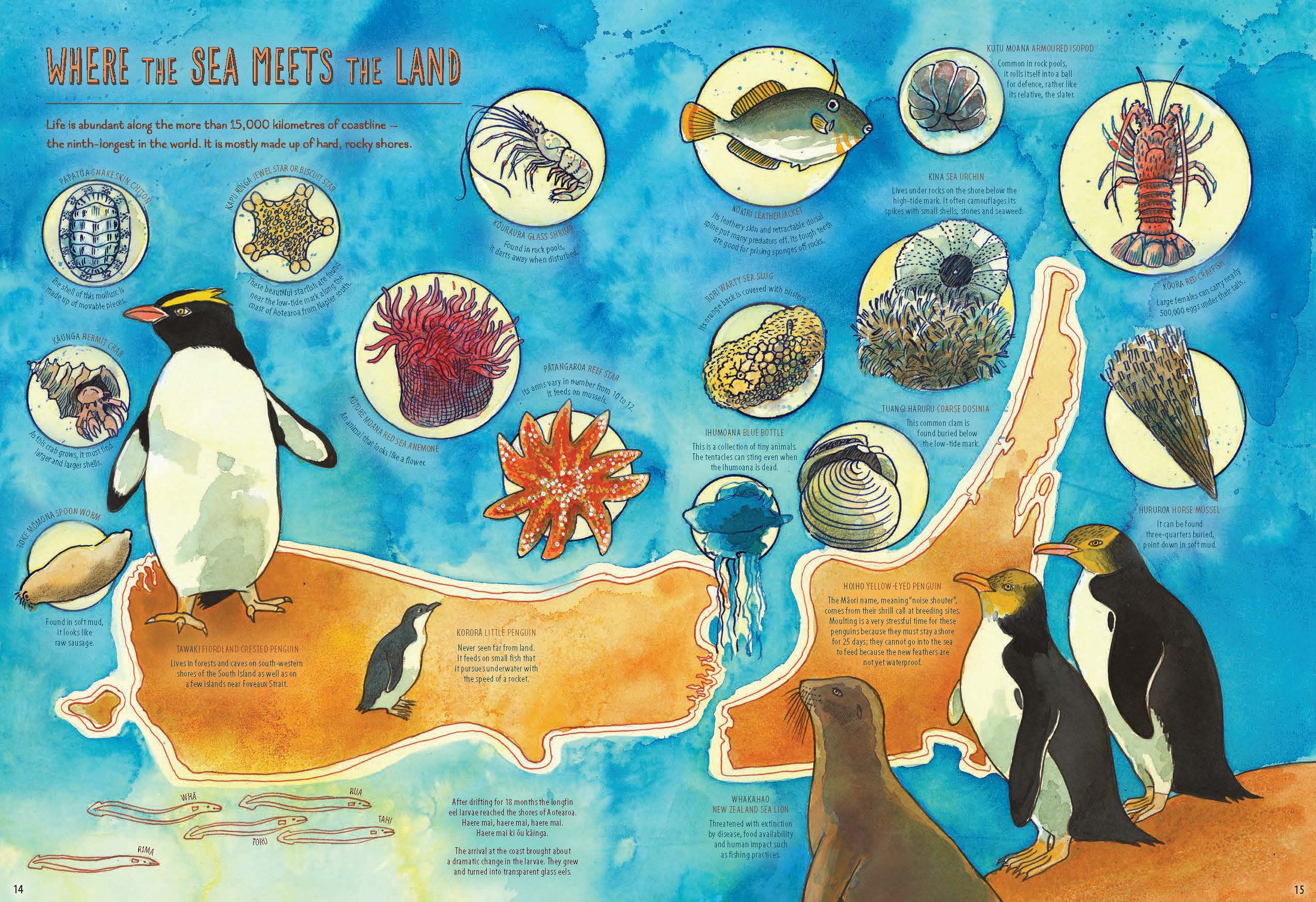

G: It is a consistent character that gives you your particular book. I researched and collected a lot of material for Wildlife of Aotearoa but then I had to then digest it so it became unified and pertinent to that particular book. You have to process things so the book has your character. You give it your flavour, don’t you?

S: Yeah. And at its most basic level, it’s our line of story and our drawn line that carries that story, that’s got to be us. For Mophead, it’s not about being the best drawer, it’s about telling the story through your unique line.

While I work digitally, I always start on paper. And as a poet, I write on paper. There’s a deep satisfaction in being able to flip back and see the work. In digital, for me it is mostly a single screen interaction.

G: I actually think that a picture book is a bit like a little movie. You have the credits, and the title at the beginning. The words and the images tell the story together. If you watch a movie with the sound off you only get half of the story. I see a picture book like that. In an ideal picture book, the words and the pictures can’t be separated.

S: We both talked about how overwriting is a necessary part of the process. It percolates, and the work gets reduced to its essential elements. I found as a writer coming into picture books – into art and text – the same writing principle of trying to ‘show, not tell’ also applies, and that’s the way I get into language. I realised one or two drawn lines could carry the information in a more interesting, evocative way.

G: I think it’s a very undervalued literary process, and people who haven’t worked in it don’t understand it and sometimes belittle it. They think that because it’s for children, it is of less importance than something that is geared towards adults. I have fought that attitude all of my career. A picture book is a much maligned, very sophisticated, deceptively simple literary form that if it works well, deserves to be looked at again and again.