How New Zealand developed an obsession with Spike Milligan’s beloved baddest witch in all the world.

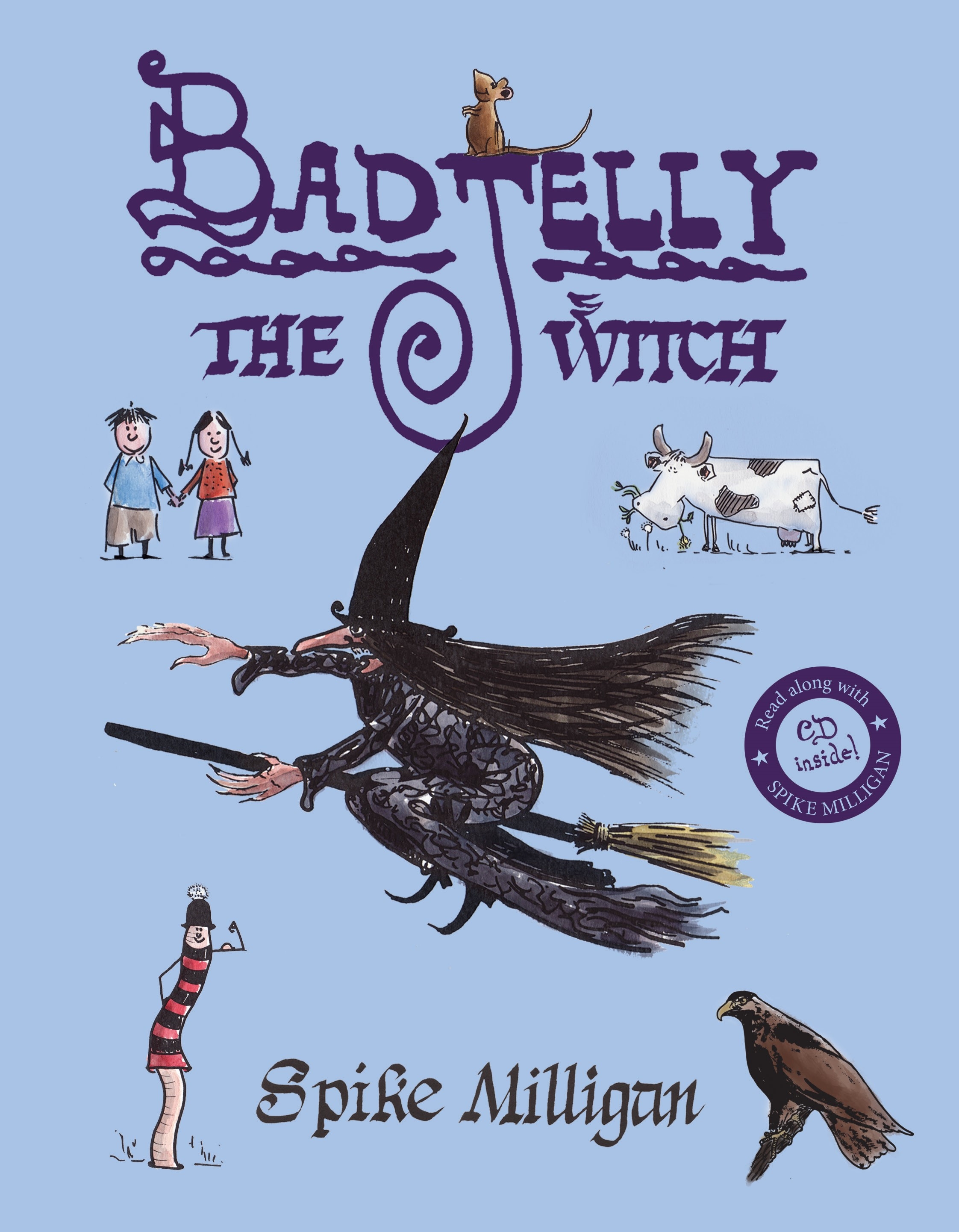

In this five-part series, Gemma Gracewood adventures through the many iterations of Spike Milligan’s Badjelly the Witch to find out why New Zealand loves her the most, and why the U.K. might finally be ready to embrace their long-neglected wickedest witch.

Spike Milligan’s Badjelly the Witch tells the hilarious and terrifying story of Tim and Rose, only six and five years old, searching for their lost cow in the woods, who was kidnapped by the self-proclaimed “baddest witch in all the world” — so bad, she turns policemen into apple trees and argues with God — God!. Tim and Rose only escape the horridible fate of boy-girl soup through the quick thinking of Dinglemouse, who was once a banana, and whose friend Jim the Eagle is not only big and strong, but also owes him money.

Badjelly the Witch is a distinctly anglophilic story, with its milking cow, castle, jam sandwiches and porridge, yet it met its greatest success on the other side of the world. Badjelly has been the most requested story on New Zealand radio. Book sales exceed 100,000. A stage adaptation is the most-licensed New Zealand play, ever. And, most wonderfully, generations of New Zealand children can recite the story back-to-front.

…most wonderfully, generations of New Zealand children can recite the story back-to-front.

I was born the year Badjelly the Witch was published, which feels about right. Spike was part of our family long before me, courtesy of ‘The Goon Show’, which Mum and Dad and the big kids listened to on NZBC’s 2YA (nowadays you’d call it RNZ National). Nobody has ever played with the medium of radio quite like The Goons. They were the most famous and influential comedy collective to come out of 1950s Britain, and remain a huge influence for comedians today. They were the soundtrack to John Lennon’s early teens; Monty Python are indebted to them; Eddie Izzard would likely not exist without them. Their surreal humour helped post-war England loosen up, and while founding members Peter Sellers, Harry Secombe and Michael Bentine are without peer, it was their creative ringleader Spike Milligan who sat above even them in terms of comic genius.

The Goons certainly had a strong influence on our family: we had a succession of pet budgies named after Goon characters — including Eccles (a Milligan character) and Bluebottle (voiced by Peter Sellers) — and we regularly exclaimed “He’s fallen in the water!” when Dad kersplatted into the pool. Many of Spike’s books have sat on our shelves for decades. He wrote and wrote and wrote: letters and limericks, plays and prose; silly verse for children, serious poems for grownups; his complex life laid out in words, a literal open book. When Spike’s singular, spectacular recorded version of Badjelly the Witch hit the airwaves in the 1970s, Binklebonk’s “Ooooh yes I caaaan” joined our family sayings, and we were all, most certainly, silly-sausages.

As I revisit the story for the eleventy-bajillionth time with my four-year-old, my adult brain has questions that never occurred to my child mind. Why did Jim the Eagle borrow money from Dinglemouse? When Badjelly bursts like a bomb, why is her magic not reversed as in other fairy tales? (It’s clear it isn’t, because Dinglemouse is still a mouse, and somewhere out there is a very law-abiding apple tree.)

The biggest question of all is why Badjelly the Witch became so huge in Aotearoa without ever achieving celebrity in her homeland. It seems she has reached every corner of New Zealand. Yet in the UK and Ireland, the book is no longer published, the plays are rarely performed, and barely anybody remembers the audio recording. But, as you and I are about to discover, that might be all about to change.

The biggest question of all is why Badjelly the Witch became so huge in Aotearoa without ever achieving celebrity in her homeland.

Top quality bedtime story action!

Badjelly the Witch smacks, in the very best way, of made-upness. ‘You don’t know, when you’re little, that there are far crappier bedtime stories. That was the level I was getting: top quality bedtime-story action!’ says Jane Milligan, Spike’s fourth child.

She’s the one to whom Badjelly the Witch is dedicated, and the books have always included the illustration ‘by Jane Milligan aged 6’ of Jim the Eagle with Tim, Rose and Dinglemouse on his back, Badjelly in hot pursuit, with her cat and her keys aboard her broomstick. ‘I can remember him asking me to do that drawing,’ she recalls. ‘I remember the paper, I remember the pens we used.’

When I tell people I am going to chat to Jane, who lives in London and is an actor and writer, they naturally want to know what it must have been like to have Spike Milligan as your dad. I tell Jane this, adding that it’s an odd question because, really, you don’t know that you’re growing up with “Spike Milligan” for a dad, do you? Isn’t he just “Dad”?

‘You’re the first person who’s ever said that, which is brilliant,’ Jane says down the line from London, where, at the time of writing and all going to plan in the current climate, she’s about to launch into rehearsals for the stage version of Sister Act alongside Whoopi Goldberg and Jennifer Saunders. ‘First of all, I never had any other dad so I don’t know any different. That was what I got, I got that dad. My dad just happened to be Spike.’ (Jane’s mum, Paddy Ridgeway, from whom she gets her musical theatre genes, married Spike, from whom she gets her funny bone, when he was a solo father with full custody of three young children: Laura, Seán and Síle. Later, a son and a daughter, from two more mothers, would expand the family.)

Bedtimes in the Milligan household were magical. Spike had rigged up a huge blackboard across a whole wall of the children’s nursery. ‘If you were still awake when he got in, he would tell a story with chalk drawings to go with it,’ Jane recalls. ‘The imagination and the words and characters were so incredibly exciting and stimulating and vivid, it was just, like, Spielberg right there. A movie in your head!’

‘The imagination and the words and characters were so incredibly exciting and stimulating and vivid, it was just, like, Spielberg right there. A movie in your head!’

Badjelly, she says, ‘was nailed down when I was about five or six. She was probably the combination of the best of all the stories he’d been telling to all four of us throughout our formative years.’ Spike readily pulled details into the story from real life: Tim and Rose’s cat Fluffybum was named after the Milligan family cat, and there’s a story going around eye specialist circles that Badjelly’s name comes from “bad jelly”, vitreous fluid that’s gone clumpy, tears at the retina, and results in retinal detachment in the eye. (Huge, if true!)

So what was it like to have Spike Milligan for a dad? ‘He was a great dad!’ Jane affirms. ‘He just had a very nice vibe. He was an incredible visionary, a compassionate human being. Very strong, as a dad, morally, for me as a kid. He never spoke to you like you were an idiot, he just spoke to you like you were on the level. It was total respect, and full excitement.’

There were painful times, “agonies with the ecstasies”. Spike was famously prone to depression; his experiences in WWII had taken their toll, as you can glean from his series of memoirs (the first volume of which is entitled Adolf Hitler: My Part in His Downfall).

Other people’s memoirs suggest he could be bracingly curt, wildly unpredictable, argumentative, even nasty — but only around other adults. ‘When he was down, he would just go to bed and watch TV and eat ice cream and be down,’ says Jane. ‘He was very sensitive, a beautiful person. He just used everything he had, and poured it down his arm into his pen onto the page. He only ever really wanted us to be happy. Just be free. Enjoy. You’re not always going to win the race.’

‘When he was down, he would just go to bed and watch TV and eat ice cream and be down,’ says Jane. ‘He was very sensitive, a beautiful person.’

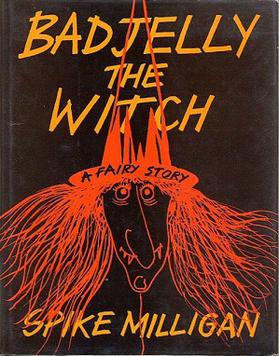

At some point in Jane’s childhood, Spike committed Badjelly the Witch to paper in his playful handwriting, with drawings of majestic Mudwiggle the Mud-Eating Worm, tiny Binklebonk the Tree Goblin, lovely Lucy the Cow, handsome Jim the Eagle, ten-eyed Dulboot the Giant. The illustrations fizz with kinetic energy. The first edition was published in 1973, but the real fun would begin the following year.

READ EPISODE TWO: “Stinky poo! Stinky poo! Knickers! Knickers! Knickers!” Composer Ed Welch remembers recording the famous Badjelly the Witch LP with Spike Milligan.

Gemma Gracewood

Gemma Gracewood is a writer, producer and director who peddles in delight. A fifth generation Pākehā New Zealander, she has toured the world in a ukulele orchestra, made award-winning shows about chain-reaction machines, and is currently the editor of Letterboxd. Her favourite saying used to be ‘you can sleep when you’re dead!’ but now she has a four year old and that’s not funny shut up.