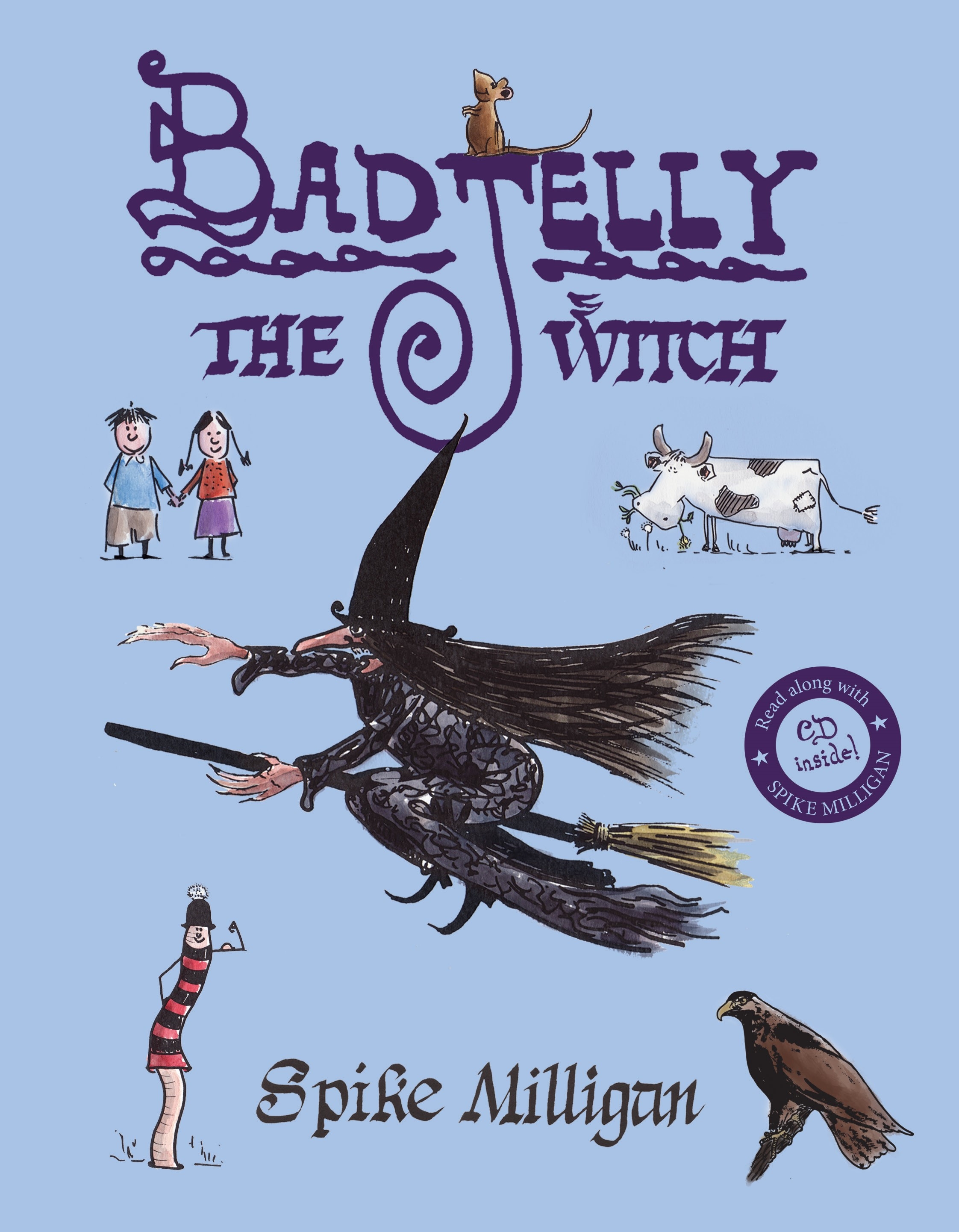

How New Zealand developed an obsession with Spike Milligan’s beloved baddest witch in all the world.

In this five-part series, Gemma Gracewood adventures through the many iterations of Spike Milligan’s Badjelly the Witch to find out why New Zealand loves her the most, and why the U.K. might finally be ready to embrace their long-neglected wickedest witch. (Read Episode Four here)

SCENE ONE: LUCY’S FIELD

Getting dark-and-night-time.

Intro music and ‘Badjelly Theme’ play.

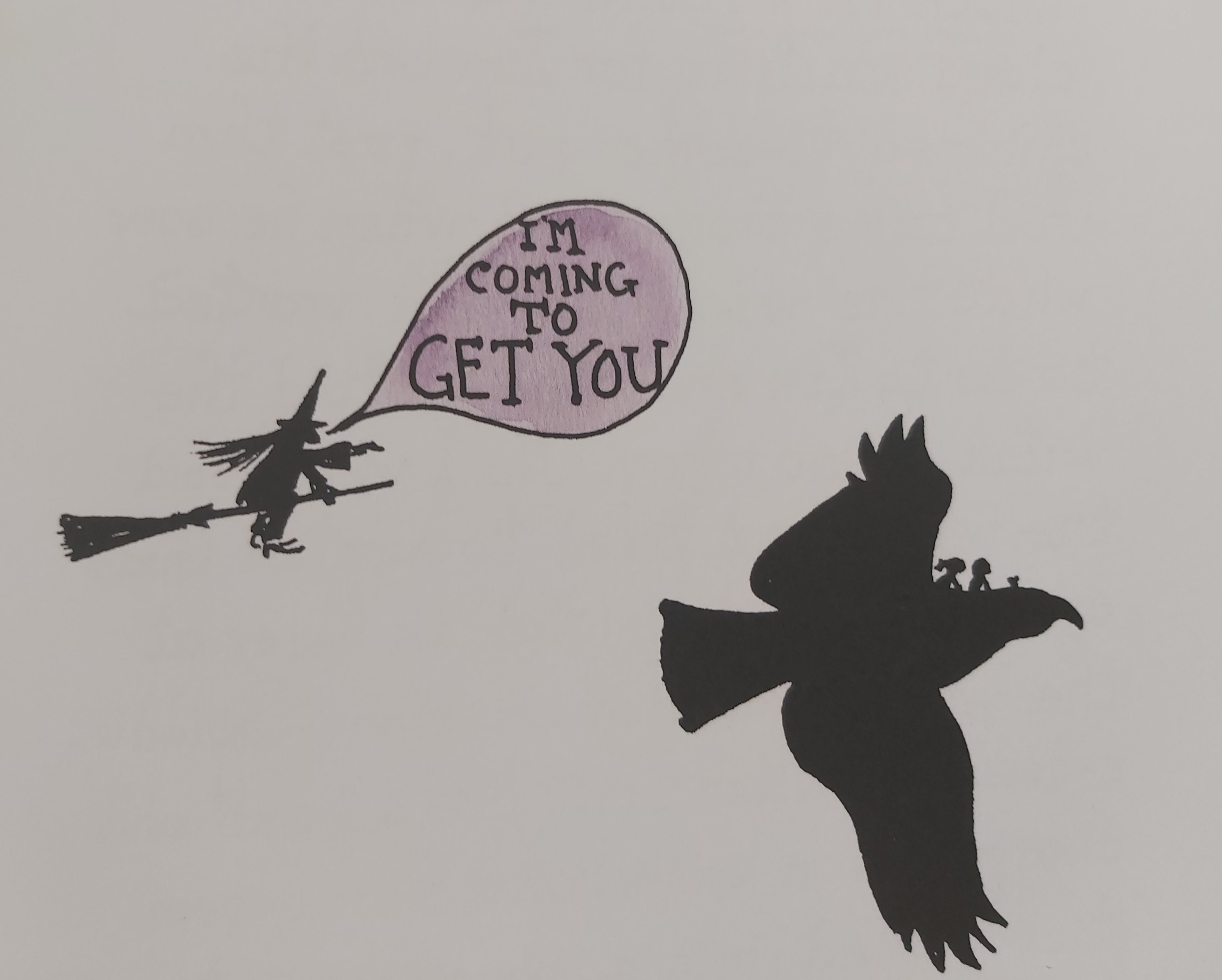

Two shadowy figures, BADJELLY and DULBOOT, loom in the eerie light…

DULBOOT: Look! There!

BADJELLY: What?

DULBOOT: Boys and girls. Lots of them.

BADJELLY: So?

DULBOOT: For your soup. I’ll catch them for you.

DULBOOT starts to lumber over to the children in the audience.

This is the opening of Alannah O’Sullivan’s 1977 stage adaptation of Badjelly the Witch. Though not a New Zealand story, it is Aotearoa’s most successful play. To date, it has been licensed for performance well over 150 times across New Zealand and Australia, reaching countless children and providing a strong leading role for many of our actresses, including Madeleine Sami, Lisa Chappell, and Pinky Agnew. Not a year goes by without Badjelly being performed somewhere in New Zealand.

Alannah’s innovation was to introduce Badjelly and her servant, Dulboot the Giant, right at the top of the stage version. In the book, it’s a good two-thirds of the way through before Badjelly appears with her nice, warm sack. ‘I knew kids were there to see Badjelly and if we waited, it was a long time,’ O’Sullivan explains. So, within minutes of the play’s opening, Dulboot and the audience are engaged in a lively ‘Oh no, she isn’t’ / ‘Oh yes, she is!’ pantomimey argument, as they all try to convince Badjelly of the presence of Lucy the Cow. (Spoiler alert: she’s behind you!)

An actress, storyliner and script editor for television, Alannah now lives in Glasgow with her Scottish partner, actor John Cairney, whom she met in New Zealand when he caught her ear with his quick sense of humour. Passionate about children’s content (‘if you don’t plant the seed, you can’t grow the tree’), she is currently script-editing a ‘very gentle, kind’ BBC children’s show called Molly and Mack. As one of seven girls in an artsy family, Alannah would often read Badjelly the Witch to her sisters’ many children, and was inspired by their reactions to put the story on the stage.

From its first production at Greytown Primary School in 1977, to community shows, to a memorable Silo Theatre outing, Alannah reckons the play is a popular choice to perform because she wrote it so that a ‘small cast could do it, a large cast could do it. You could do it if you had money, if you didn’t have money.’ Ultimately, though, the main attraction is Badjelly. ‘You need a really full, whole-hearted antagonist for any play. She’s one of the best.’

Ultimately, though, the main attraction is Badjelly. ‘You need a really full, whole-hearted antagonist for any play. She’s one of the best.’

More recently, veteran children’s theatre producer Tim Bray, whose company turns 30 next year, developed his own stage version of Badjelly the Witch, full of lunacy and absurdity. A fan of the Monty Python troupe, who in turn were influenced by Spike Milligan, Tim wanted to create ‘my own style of Badjelly that spoke to that’.

Tim Bray Productions’ version starts with a big fanfare, then the curtains get stuck. They shut, they open, they get stuck, they jiggle. Next, a prince rides on and launches into a monologue, whereupon the narrator tells him, ‘You’re in the wrong play!’. ‘It’s just rich pickings for craziness and silliness,’ says Tim. ‘With some other stories, you wouldn’t mess with them. Spike almost gives you permission to just go for it.’

‘It’s just rich pickings for craziness and silliness… With some other stories, you wouldn’t mess with them. Spike almost gives you permission to just go for it.’

Curiously, given other Badjelly-related decisions, Spike’s manager Norma Farnes readily granted stage adaptation rights to O’Sullivan and Bray, and to the NZ playwrights’ agency Playmarket to represent both scripts in Australia and New Zealand. It’s almost as if what happened below the equator didn’t really concern her — until people tried to mount the plays in the UK. Then it was a hard no. Until now.

A few months ago, Playmarket’s Murray Lynch met Jane Milligan for lunch. His specific agenda was to see if the new Spike Milligan Productions team would be open to extending the territories that Playmarket represents for the two New Zealand adaptations. ‘I just mentioned that, previously, we hadn’t had the UK as a territory, and would they be open to us representing that?’ Murray recalls. Fortunately, team Badjelly are fans of the idea, especially Alannah O’Sullivan’s script. The upshot, reports Murray, is ‘we’re delighted to have the territories that we represent extended. I hope that the rest of the world beyond New Zealand is awake to the joys of Badjelly! It’s so charmingly mad.’

‘I hope that the rest of the world beyond New Zealand is awake to the joys of Badjelly! It’s so charmingly mad.’

The family’s new Badjelly agent, Nathan Graves, is starting to think about a future Edinburgh Fringe season of O’Sullivan’s version of Badjelly, to reintroduce the witch to her homeland. It’s terrific to imagine that children across the UK and Ireland might finally enjoy the thrill of her scares, but she’ll always be ours.

My feeling is Badjelly captivated New Zealanders thanks to a happy bunch of factors that tickle us right where we like to be tickled. There’s a sort of give-it-a-crackness to the book, the record and the plays that vibe with our natural personality as a nation. It’s got a cast of anthropomorphised animals, and we do love our talking pets. Every time I read the story aloud, I can hear the inner workings of Spike Milligan’s brain. His charming silly-mistakery makes it feel okay to be a grownup who tries really, really hard, and sometimes fails. You really can’t read Badjelly the Witch to a child without fully committing. Spike gives us permission to be brilliant, humane, imperfect idiots. New Zealanders, in a nutshell.

You really can’t read Badjelly the Witch to a child without fully committing. Spike gives us permission to be brilliant, humane, imperfect idiots. New Zealanders, in a nutshell.

In 2023, Badjelly the Witch will be 50 and she needs the very best birthday party. Imagine: a sold-out Spark Arena, Ed Welch conducting the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra, comedians like Jemaine and Rose and Rhys and The Topp Twins performing the entire Badjelly the Witch album, everyone in their gold-buckled red-shoed finery. Dick Weir as the Voice of God, and as many Milligans involved as want to be. Who’s in?!

But even as we imagine Badjelly’s future, it’s also becoming more common, and necessary, to re-examine beloved cultural works through fresh lenses.

Normies and Freaks; God and Bare-bottoms

With 2020 glasses on, you could say that the main grumbles about Badjelly the Witch — and this is somewhat clutching at straws — are some dated fairy tale tropes, a majority-male cast, and that witches get a bad rap. The heteronormativity of Tim and Rose’s family could do with an update, and there’s a God bit that can be tricky for some readers.’

Should all the wicked witches get wiped out of the storybooks now that history recognises the traumas visited upon our Wiccan foremothers, or is there room on the broom for variety? The feminist argument goes that if we want strong female characters, we have to be prepared for them to span the spectrum of good and evil. Alannah O’Sullivan agrees. ‘I’ve always just loved her. She is so all-embracing of badness. I find that absolute commitment really attractive. There’s no half-measure.’

And what to do about the ‘God bit’? In a hilarious deus ex machina, Badjelly is destroyed by the literal finger of God — the tell-tale trick of a desperate dad trying to wrap things up and get his children to sleep. This can be awkward for parents who haven’t yet had spirituality conversations with their children. Indeed, the BBC asked Spike to leave God out of their radio play (which he did) but Jane Milligan loves the bit. ‘You can’t go any higher than that, can you! She ends up fighting with God — God! It’s the ultimate battle, isn’t it?’

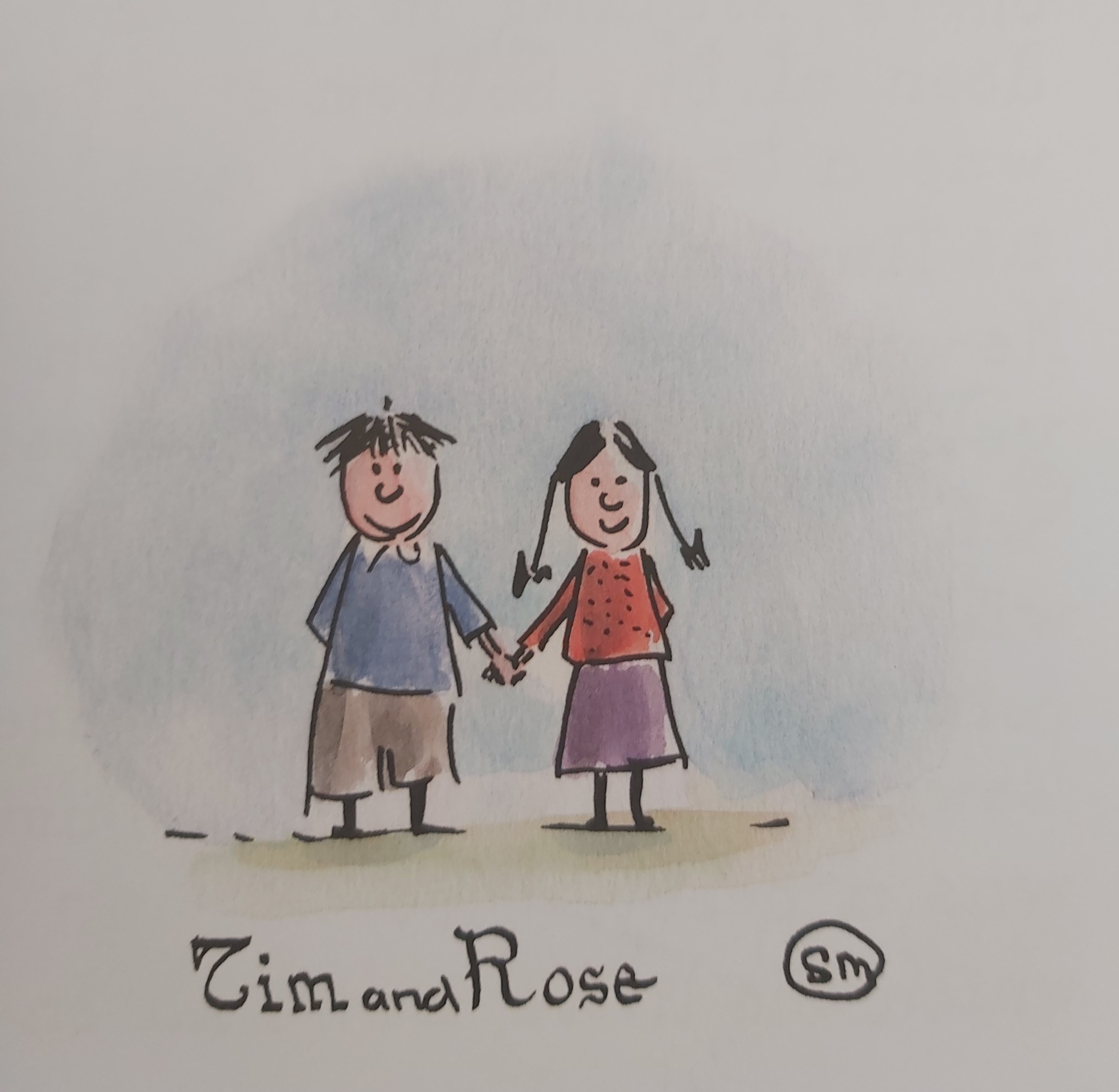

As for the binary nature of Tim and Rose’s family, well, apart from the neat trick grownups can do of pronoun-switching as they read along (Tim Bray often casts against gender in his Badjelly productions, too), Finn McCahon-Jones offers a perspective on why we ought not tie ourselves up too much about this. ‘Tim and Rose are on equal footing. It’s not like the girl’s any more useless than the boy, which was often typical of those stories of the time. I always thought they were really compassionate, really sweet, good-hearted kids.’

‘Tim and Rose are on equal footing. It’s not like the girl’s any more useless than the boy, which was often typical of those stories of the time.’

What Tim and Rose represent as ‘normies’, he thinks, is their willingness to embrace their freaky new friends, and even bring them home at the end of the tale. ‘It’s that coming-of-age story: they’ve gone into the world, they’ve had a really intense experience, and right at the end, they own their story. I always get a bit teary about that.’

All said, Badjelly the Witch endures through a timeless message: little and good can win against big and bad, especially with friends helping. Also: nonsense never goes out of style. And, always lend money to eagles.

All said, Badjelly the Witch endures through a timeless message: little and good can win against big and bad, especially with friends helping.

Terence Alan ‘Spike’ Milligan, KBE, died, aged 83, in 2002. At his request, his family had his headstone inscribed with the words ‘I told you I was ill’ (written in Irish — Dúirt mé leat go raibh mé breoite — to avoid the ire of the diocese).

My own Dad died in 2009 and I’m so sad he won’t read this story, but he would have loved that I was doing it. He was a stickler for billable hours, but he was also afflicted with silly-billy-itis, so he’d have completely understood why I took on a commission for a short piece on why Badjelly is beloved in New Zealand’ and expanded it well beyond my often-solo-mumming capacity, writing thousands of words around my day-job, through lice and tummy bugs and the black dog, talking to Glasgow and London and South Devon and Wellington late into the night and the early mornings, spending my writer’s fee gobbling up different editions of the book and the LP, and finally delivering the opus you’re currently reading a quite-annoying six months beyond deadline.

Because the first rule of Dead Dads Club is to always talk about your dad, it feels natural to end this journey by asking Jane what she misses the most about Spike. ‘I miss the power he had to change things. We need people like him at the moment. He always used his fame and his money to help other people who were struggling. And that is probably the best, the only reason to be rich and famous. It should be. It’s the only reason to have money. That you can do something with it. Because keeping it and putting it into lip fillers is not good enough.’

‘I miss the power he had to change things. We need people like him at the moment. He always used his fame and his money to help other people who were struggling. And that is probably the best, the only reason to be rich and famous.’

And there’s something else Jane needs to say to everyone out there buying the book for a new generation of bedtimes, listening to it in the car, phoning the radio station to request it again: ‘My message is thank you for keeping Badjelly alive! What can I say? I had a ‘bad jelly’ at my wedding, as one of my desserts. That’s what I asked for, a Badjelly the Witch jelly! It was the hat of Badjelly the Witch. I mean, you know, she lives on in my world. Thank you to New Zealand for still loving Badjelly the Witch.’

P.S. These days, the Badjelly the Witch LP is on Spotify for all to hear.

Gemma would like to thank Jane Milligan, Ed Welch, Salesi Le’ota, Jeremy Ansell, Paul Horan, John Forde, Tracey Monastra, and her siblings Jolisa, Greg and Ben for their support and feedback, Wiremu for his constant enthusiasm as a captive audience, The Sapling for inspiration and patience, and would very much like to dedicate this story to the memories of Spike Milligan and Wallace Gracewood. Rhubarb, rhubarb, rhubarb.

Gemma Gracewood

Gemma Gracewood is a writer, producer and director who peddles in delight. A fifth generation Pākehā New Zealander, she has toured the world in a ukulele orchestra, made award-winning shows about chain-reaction machines, and is currently the editor of Letterboxd. Her favourite saying used to be ‘you can sleep when you’re dead!’ but now she has a four year old and that’s not funny shut up.