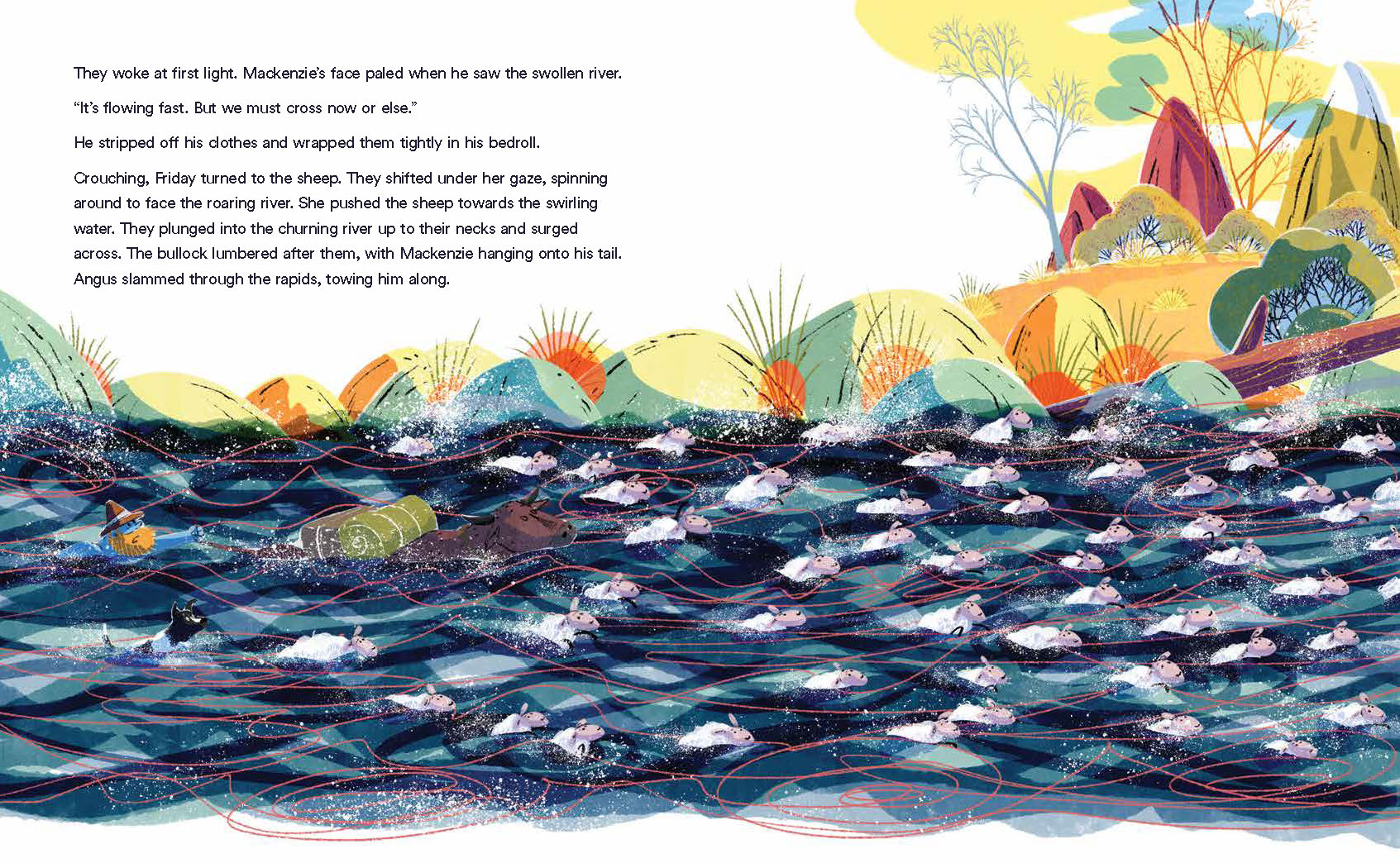

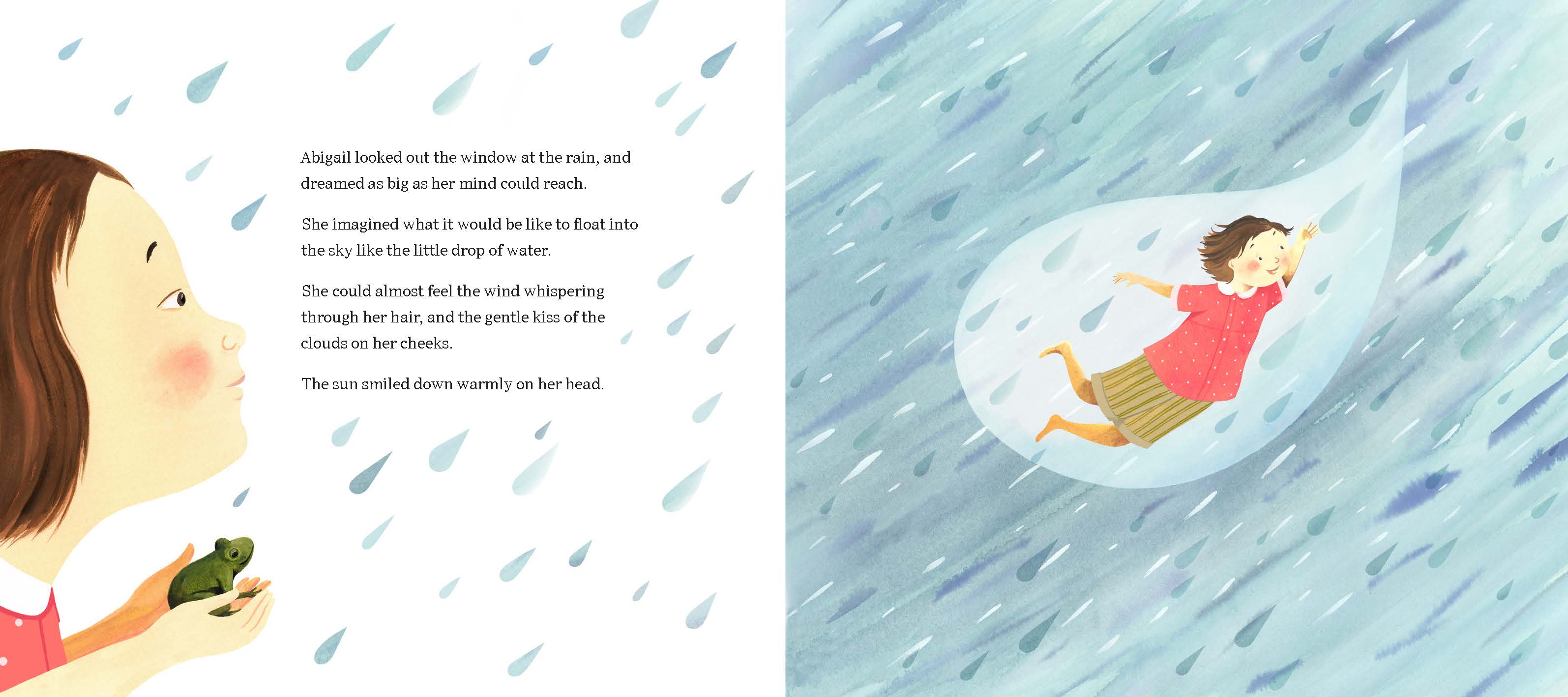

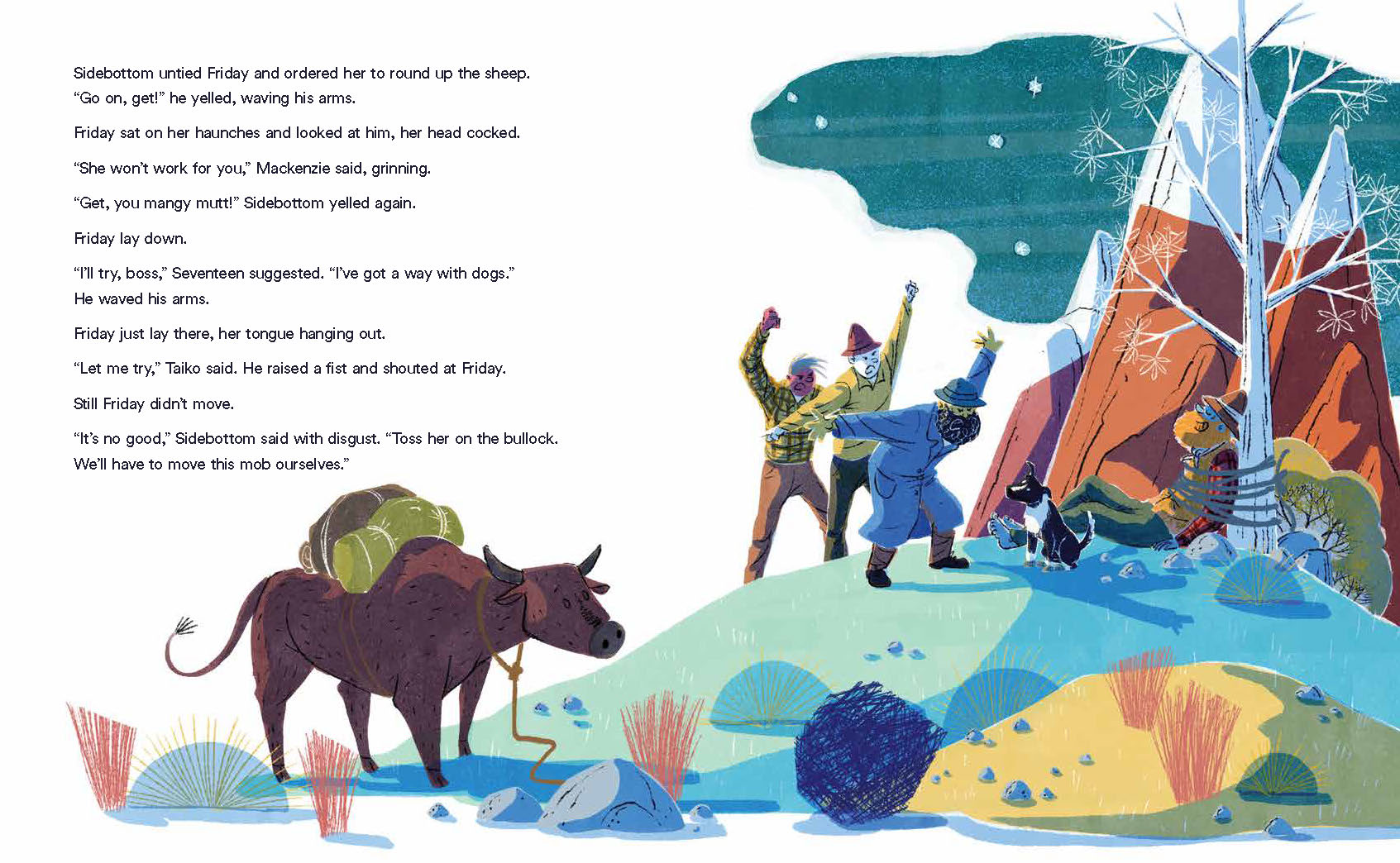

Children’s authors Matthew Cunningham and Susan Brocker caught up over email to talk story ideas, inspiration, and wrangling animals in text. Matthew is the author of the Abigail series, the most recent of which is Abigail and the Restless Raindrop (Penguin Random House NZ), while Susan is the author of new Mackenzie country tale Friday the Rebel Dog (Scholastic NZ).

Matthew Cunningham: Kia ora Susan! I hope you don’t mind, but I did a little googling about you before our co-interview, and I discovered that we both have history degrees!

When it comes to fiction, does history play a role in what you are inspired to write about?

Susan Brocker: Yes, history has been the inspiration for many of my stories. I think New Zealand’s past is full of wonderful stories just waiting to be told, especially to our children.

When I grew up, our school library had very few books that reflected Aotearoa’s past. It wasn’t until I attended university to study history that I finally came in contact with our heritage. Thankfully, the scene has changed and we now have great New Zealand children’s authors writing about our rich and varied past.

As I sit down to write historical fiction, I try to let the story take hold of the reader and lead them on an exciting journey to a different time and place. But I also try to ensure my fiction is based firmly on historical fact. Sometimes when writing for younger children this can be difficult, especially if the facts are sad or brutal; this is when I let the characters speak to the reader in a gentler voice.

As I sit down to write historical fiction, I try to let the story take hold of the reader and lead them on an exciting journey to a different time and place.

SB: I see that as a historian you have written many academic pieces for adults. How do you manage to put aside your academic hat and write such lovely lyrical stories for children?

MC: The short answer is, with great difficulty!

In addition to history and children’s fiction, I also write adult fiction – science and fantasy, mostly – so being able to shift between the different hats is not always easy. Wearing my academic hat, I am driven by the need to break down complex webs of causality into concise and structured narratives. But my fiction is driven by characters who never have the whole picture, and whose perceptions of the world are imprecise and biased.

There are some commonalities though. All of my writing is underpinned by a desire to communicate complex ideas in a way that is clear and engaging. I also find that a good eye for storytelling helps to make history more compelling.I think it’s about getting into the right headspace for different writing styles. I usually start a writing day by re-reading what I most recently wrote on that subject, which gets me in the ‘zone’.

MC: I’ve read that you get many of your ideas while riding. What’s your process for translating these moments of inspiration into words on paper?

SB: I think it’s the physical activity but also the absolute freedom I feel from any constraints. I can let my imagination run wild without worrying about the plot or structure of a story. The ideas can simply flow one way or another and take surprising turns.

It’s not until I get home and sit in front of my desk that I jot these ideas down in the same notebook I always use, and think about them coherently. Some ideas get tossed immediately, while I’ll play around with others until one starts to haunt my thoughts. Once I have a burning idea, I plot it out to see where I’m going and if it will work.

Some ideas get tossed immediately, while I’ll play around with others until one starts to haunt my thoughts.

Once I’m happy with the structure, I begin writing. Then I lose myself and don’t worry about refining and editing until the very end. During this time, the story can take on a life of its own and lead me down unexpected paths, but I always know where I’m ultimately heading.

Once I’ve finished writing, the real work begins – and that’s the editing. I prune back my work ruthlessly, always keeping in mind my readers and what would most inspire them to keep reading.

SB: How do you approach your writing, Matthew? I’m also interested to know how you find writing with an illustrator. Do you consciously think of what Sarah might illustrate on each page?

MC: I get random flashes of inspiration during the day – most often when I’m doing some menial task that lets my mind wander. I like to let the ideas percolate in my brain for a while before committing anything to paper. I used to get really worried that if I didn’t jot down every little idea that popped into my head, I would forget them! But I’ve come to realise that good ideas will continue to evolve in my mind until they are ready.

I don’t tend to have the full story in my head before I start writing. Sometimes I have an idea of where it’s going – a roadmap of sorts – but I usually find myself taking surprising detours once I put pen to paper.

The Abigail books are a bit of an exception though. They were much more developed before I wrote them, since they started life as actual stories I made up for my daughter.

I don’t tend to think well visually, so I am quite happy trusting Sarah to come up with something amazing (as she always does).

MC: I love how some of your books vary between human and animal perspectives. How do you decide who your point of view character is going to be?

SB: I think my stories are more character-driven rather than plot-driven, so usually I start with the idea in my mind from the character’s viewpoint.

Sometimes the character is the original stimulus for the idea, as in my stories about Bess the warhorse and other historical animals I’ve written about. For instance, I’ve just finished another true story about a tomcat called Mrs Chippy who sailed aboard Endurance on Shackleton’s beleaguered expedition.

The story is told from Mrs Chippy’s point of view, so it was his experiences (Mrs Chippy was actually a tom) that I write about. This can be a lot of fun, but also offers up its own challenges, especially when your main animal protagonist meets a sticky end as with poor Mrs Chippy!

I find writing from an animal’s viewpoint is an effective way to tell difficult stories to children.

Mostly, though, I find writing from an animal’s viewpoint is an effective way to tell difficult stories to children. This is especially true for some of my stories set in wartime, such as Bess, and my junior novel, Dreams of Warriors, but also for my books that confront difficult family situations, such as Saving Sam and The Wolf in the Wardrobe. Children can follow the journey of the animal and relate to the situation through their eyes. It’s how they cope and become stronger that is the backbone of many of my stories.

SB: I was interested to read that you also write science and fantasy fiction for adults. Do you think you would consider writing a novel in this genre for older children?

MC: I’ve definitely thought about it. The great thing about science and fantasy fiction is that you can use it to explore real-world issues in a fictional setting. I’m currently working on a fantasy novel set on a fictional colonial frontier, which deals with big themes like imperialism, racism, feminism, suffrage, and resistance. I’d love to write something similar for older children, but I’ve yet to resolve how I’d approach it in a way that’s accessible and appropriate for a younger audience.

I’m currently working on a fantasy novel set on a fictional colonial frontier, which deals with big themes like imperialism, racism, feminism, suffrage, and resistance.

MC: I’ve noticed a strong rural theme running through many of your books – what is it about the country that appeals to you when you write?

SB: Ha, yes, I guess I’m a country girl at heart! We live on a small farm out of Tauranga where I have many pets: cats, dogs, horses, and a herd of goats, as well as rescue animals that come and go on their journey to their forever homes.Many of these animals have been the inspiration for my books, such as Layla, my old shepherd that inspired Saving Sam, and Yogi, who was the inspiration for The Wolf and the Wardrobe. And I like setting my stories in the wilder areas of the countryside where many adventures are possible and the protagonist has to take on the wilds as well as their inner demons.

I like setting my stories in the wilder areas of the countryside where many adventures are possible and the protagonist has to take on the wilds as well as their inner demons.

SB: When you are writing science and fantasy fiction, I guess you need to create fantasy worlds for your characters. How do you go about creating this imaginary setting in your mind then get it down on paper?

MC: It’s very much an iterative process. I draw a lot from history. The first seed of inspiration is usually a high-level idea, like ‘hey, wouldn’t it be interesting to write a fantasy book set on a colonial frontier?’ Then I let it percolate for a bit, and my mind will start padding it out.

This can be a short or a very long process, depending on what I’m writing. For a short story, it could be a couple of days to a couple of weeks. But I’ve been thinking about the world for my current fantasy novel for almost two decades. I’ve written hundreds of thousands of words over that time – fragments of books that never were, short stories that never found a home. It’s evolved significantly since I started studying history, from a more standard fantasy setting to an early industrial colonial frontier.

I don’t really start building the minutiae of the world until I start writing. This allows it to emerge organically as the characters grow. It’s kind of like we’re discovering the world together.

Friday the Rebel Dog incorporates elements of tikanga Māori and mātauranga Māori, and Restless Spirit – Te Wairua Whakariuka uses a dual te reo Māori / te reo Pākehā title. Is te ao Māori a common theme in your work? How do you go about building your understanding of te ao Māori before you write?

SB: As a lot of my stories are set in New Zealand, I often incorporate te ao Māori into my work, but only if it’s relevant to the story I’m telling. In other words, I wouldn’t use tikanga Māori and mātauranga Māori for the sake of it, but when it is an important element of the story I certainly do.

I’ve always had a great interest in te ao Māori and learnt some te reo when I was younger, but if I use it in my work I like to check with the local Māori where the story is set to see that it is relevant and correct first.

I’ve always had a great interest in te ao Māori, but if I use it in my work I like to check with the local Māori where the story is set to see that it is relevant and correct first.

Matthew, if you had to give one major source of inspiration for most of your fiction, would you say it was history as it is with myself?

MC: I don’t think I have just one major source of inspiration, but history is definitely one of them! Underneath it all, I think I just like the art of storytelling. There’s something very primal about it; stories transcend borders, language, and culture. They free us of the constraints of the real world. They let us take what is, and imagine what could be.

My final question is, can we expect more ‘true New Zealand stories’ from you and Raymond McGrath? You mentioned Mrs Chippy and the Endurance…

SB: Yes, most definitely. We’ll soon be working on the true story of Pelorus Jack, and then perhaps the tale of Captain Scott’s sled dog, Osman the Great, in between my writing another adventure novel set in Mount Aspiring National Park. Fun!

And you, Matthew? What will be your next fiction piece? I hope Abigail joins us again soon with her delightful questions.

MC: I certainly hope there will be more Abigail stories, but it all depends on how well the first two do! I’ve got about half a dozen more Abigail stories lined up, and there’s really no limit of big questions to address. I’ve written a few other children’s stories that my agent is currently trying to find a home for, and I’m slowly chipping away at my colonial fantasy novel alongside two history books.

I’ve got about half a dozen more Abigail stories lined up, and there’s really no limit of big questions to address.

Finding time for all of these projects when I work four days a week is not an easy task, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. Well, apart from being a rich and famous author who could afford to write full-time!