The latest curiously good Aotearoa title from Gecko Press is packed with mystery, evocative illustration and all kinds of goodness! The Inkberg Enigma, by Jonathan King, is out now – but before you rush out to buy a copy, you can build up your anticipation with an interview with Jonathan by fellow Kiwi cartoonist, Eddie Monotone.

The Inkberg Enigma is Jonathan King’s first full-length graphic novel, but he’s not a newcomer to comics – and he’s certainly no stranger to storytelling. New Zealanders may know him better as a filmmaker. Remember Black Sheep? Under the Mountain? That guy.

Of the two, The Inkberg Enigma has more in common with Under the Mountain: it’s a YA story about two kids battling against a mysterious adult conspiracy, confronting their own fears and learning that the world is much bigger than they realised.

Like a lot of Jonathan’s other work, it’s utterly Kiwi. From the landscape and language to the inescapable tie to the ocean, Enigma shows what a traditional adventure comic looks like embedded in coastal New Zealand.

Like a lot of Jonathan’s other work, it’s utterly Kiwi.

The town of Aurora is fictional, but Jonathan says that visually, it’s based strongly on Lyttelton. And the way the entire town revolves around a single, struggling industry (in this case fishing) will be depressingly familiar to anyone who’s been outside of the main centres. That said, Jonathan was careful to try and make the book accessible to overseas readers too.

‘It’s neat if you can see the world the work came from in the work. I hope any New Zealander would look at it and recognise it as New Zealand, but hopefully the rest of the world doesn’t go “ew, where’s that happening”, you know? You could believe it was Northern California or New South Wales or wherever.’

The Inkberg Enigma is Jonathan’s first comics project at this scale, and he says the process of creating the book was a learning experience.

‘I’d written films, but all of my short comic stories I wrote as I drew, just thumbnailed and pencilled and then the story was there. So I’d never worked out how to write a bigger thing, but I felt I didn’t want to sit and write a script like a film. My longest comic before this was maybe 12 pages. So this is far and away the most I’d ever done, and I must say I had underestimated how challenging it was going to be.’

…I must say I had underestimated how challenging it was going to be…

‘I’m just super looking forward to other human beings reading it, basically. I’m quite jealous of people who have been working on things and putting them online as they go. That was one of the hardest aspects – to be off the radar for three years working on something was quite strange and hard.’

While The Inkberg Enigma is set in the present day, its style – fashion, architecture, capitalism – feels very last century. The opening scene is subtly timeless, with characters in wartime-style knitted vests coexisting beside others in sunnies and t-shirts. It took me until page 12, when the main character goes into an antique shop, to realise what the time period of this comic is: it’s Tintin, with its anachronistic, always modern but always mid-20th Century setting.

When I mention this to Jonathan I start by saying I don’t want to call the story old-fashioned because it sounds negative, but he cuts me off. ‘Oh, I’d be happy with old-fashioned!’

The characters in The Inkberg Enigma use Wikipedia, but they also go to the museum on foot. They primarily live in a tactile world, rather than a digital one. The story progresses through physical action, and social media doesn’t get a mention. While this can partly be attributed to the genre Jonathan’s working in, which had its heyday in the mid 20th Century – it also comes from a practical storytelling standpoint.

[The characters] primarily live in a tactile world, rather than a digital one.

‘I mean, cellphones are bad for stories, you know?’ Jonathan says. ‘You need to have a moment in films where people go “no signal!” because cellphones are just really bad for story drama and you need to find a way to stop people sharing information and things.

‘And you know, kids going like that all day [mimes scrolling on a phone] is kinda not great for getting into adventures. So I guess the kids in the book are out of time a little bit, even if the world is current. That was probably a conscious choice, because I wanted them to be the kind of people who would get into adventures and see the world in a way where you can still have adventures. I’d hope that my kids can still get into adventurous situations.

‘The main character is a bookworm and obsessed with books and things, so that’s maybe out of time too. And I’m as guilty as anyone of having trouble reading books now compared to looking at things online.’

If adventure and horror are points on a genre spectrum, The Inkberg Enigma sits squarely in the middle. The kids have knockabout fun solving mysteries but there’s an undercurrent of menace, small-town secrets and a heavy dose of Lovecraftian otherness. Given his history with projects like Black Sheep and The Tattooist, I asked Jonathan if it was fair to say he was a horror guy.

‘I’m not a horror guy necessarily, but everything I’ve made has sort of been in the fantastic realm,’ he says. ‘I like scary stuff and creepiness and creatures and magic and monsters and things, but there’s a sort of meanness about some horror that I don’t really like … I don’t quite have the stomach for being too mean to people or putting people into terrible situations. You want to put your characters through drama and maybe through the wringer, but there’s a sort of sadism I can’t handle.’

‘I don’t quite have the stomach for being too mean to people or putting people into terrible situations.’

‘Mystery and adventure were something I initially talked to Gecko about, I was calling the book an adventure story for a long time. Mystery and adventure were the common ground that we started on here. So I guess I had quite a clear picture in my head of where I wanted to pitch it. I mean I guess I always knew that people weren’t going to get their guts ripped out, or there wasn’t really going to be gunplay in the book, for example. Someone may have held a gun at one stage in a very early draft, but straight away I had a sense that I didn’t want to do that.’

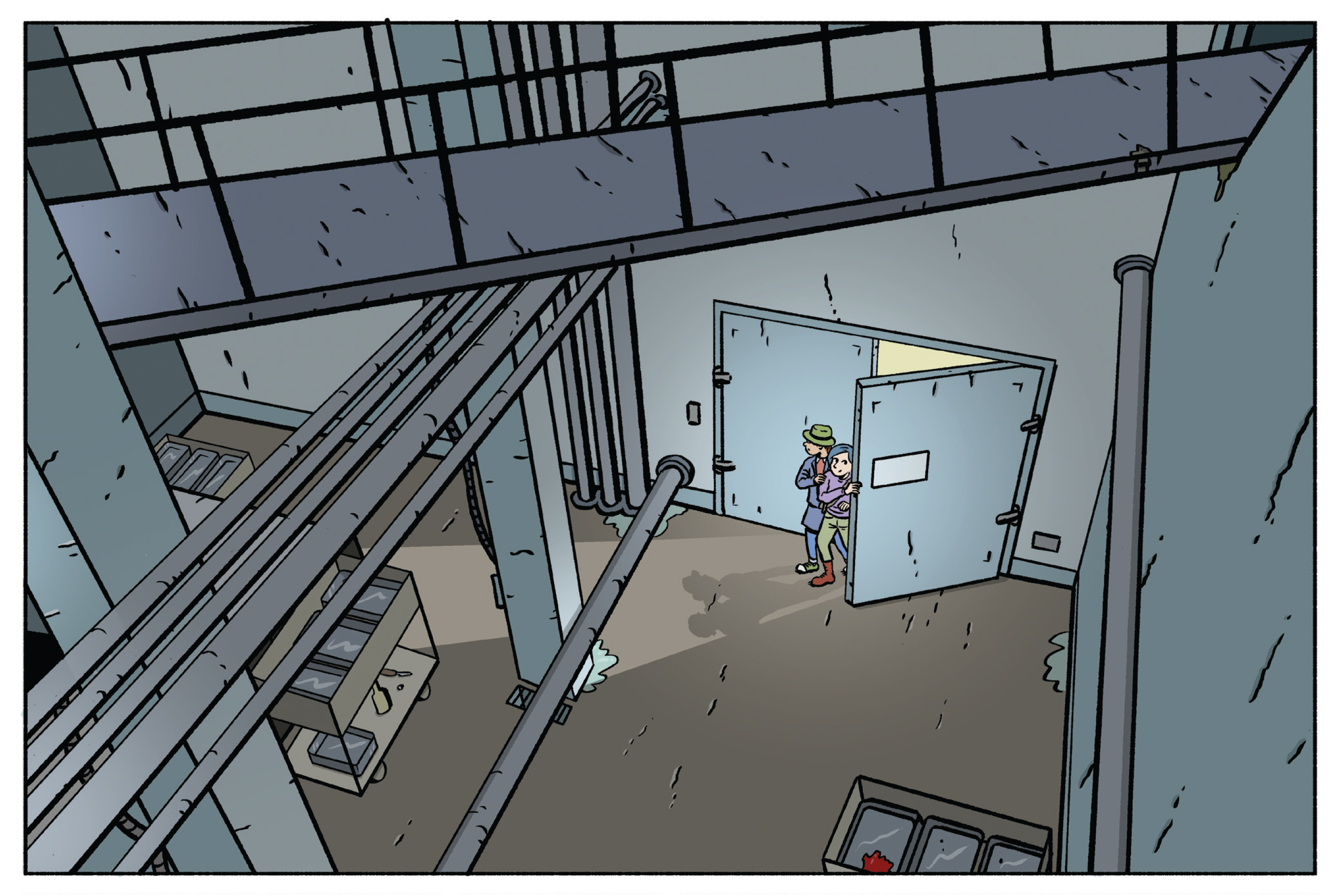

Jonathan is clear that he thinks of The Inkberg Enigma as an adventure story rather than a horror, and visually it feels more at home next to Tintin or Hilda than the work of Mike Mignola or Stephen Gammell. The lines are crisp, and the book is coloured in a flat, European style that keeps the action clear. Given the clarity of his framing and transitions, it’s not at all surprising that he comes from a film background. The focus is always on storytelling rather than illustrative grandstanding.

Which isn’t to say it’s not pretty – Jonathan is an accomplished artist and the world of Inkberg is aesthetically pleasing, well balanced between cartoon expressiveness and grounded draftsmanship.

Intentional or not, the horror elements are a key part of the book. It’s hard to do a New Zealand story without the sea playing a role, and in The Inkberg Enigma it’s presented as a source of opportunity, enlightenment, and awful, writhing monstrosities. ‘I think it got a bit tentaclier as I went on…’ Jonathan says. ‘It did get a bit Lovecraftier.’

When I ask Jonathan about what he was reading as a kid, the origins for Inkberg are pretty clear.

‘Tintin was huge for me when I was younger,’ he tells me. ‘I got my first Tintin book when I was four. The Three Investigators books were huge too. By about 13 or maybe a bit older I was reading Stephen King. And as a kid my favourite Tintin books had a scariness in them too. A combination of being into comics and creepy, monstery stuff.’

Despite the range of media that Jonathan’s influences come in, what strikes me about The Inkberg Enigma is that it feels so comfortable as a comic book. Jonathan isn’t new to cartooning, and it shows. This isn’t a case of someone from film slumming it in the cheaper medium of comics. This is a book by someone who cares about the craft and takes pride in the storytelling that only comics can do.

This is a book by someone who cares about the craft and takes pride in the storytelling that only comics can do.

‘Comics are just such a great medium for telling stories,’ Jonathan says, ‘And that’s what I love about them. And I feel a little bit this way about film making too: that lines and colours on a page – or pixels on a screen, even – can become a world is kinda magic, it’s an incredible alchemy.’

Eddie Monotone

Eddie Monotone is a cartoonist, illustrator and parent. He has been a part of the Kiwi comics scene for many years, publishing comics and cartoons both in print and online. When he’s not making comics he’s probably thinking about comics, and sharing those thoughts with anyone who’ll listen. www.edmocentral.com