It’s a good time to be curling up somewhere cosy at home with a good book. For the eight to twelves in your life, there are some brilliant new releases to look into. Sarah Forster has reviewed four new titles that pack in adventure, awareness and intrigue.

The Ghosts on the Hill, by Bill Nagelkerke (Ahoy! / The Cuba Press)

This is the first time in a few years I have seen the renowned name Bill Nagelkerke attached to a physical book, and it’s a lovely wee thing from Cuba Press, with a nice cover and internal illustrations by Theo Macdonald.

The Ghosts on the Hill tells a true story of the disappearance of two young boys on the Bridle Path from Whakaraupō / Lyttelton to Ōtautahi / Christchurch, a path which still exists today. Nagelkerke weaves a tale featuring Elsie, a young girl who encounters Archie and Davie during their day wagging school and blames herself for their disappearance. She knows there are patupaiarehe in the hills because her Pa told her so: ‘When the clouds from the south-west settle on the hilltops then the patupaiarehe are there, watching and waiting.’

Nagelkerke weaves a tale featuring Elsie, a young girl who encounters Archie and Davie during their day wagging school and blames herself for their disappearance.

Elsie enjoys nothing more than fishing on the harbour, with her friend Mr Jones, who keeps an eye on her. He hassles her about school, but this is 1884 and school attendance, while officially compulsory, was seen as optional.

‘Sometimes Elsie wishes she could screech like a seagull. She wishes she could fly like one too.’

Her Pa lives at the kāinga in Rāpaki, while her mother and brother live in Whakaraupō. Her aunt is about to have a baby, and her mother tells her off for not responding to her call home, as she had hoped to send her with some baby clothes on the train through the new tunnel through the hill.

The feel of the book is one of a close community, without Nagelkerke having to introduce any more than the bare minimum number of characters to tell the story well. Snippets of the true story are provided as newspaper headlines throughout the book, which keeps the tragedy of Archie and Davie in mind as we follow Elsie who faces her fears on her journey taking the baby clothes across the hill a year later.

The feel of the book is one of a close community, without Nagelkerke having to introduce any more than the bare minimum number of characters to tell the story well.

The plot is woven dextrously by Nagelkerke and you feel as though you are back in 1884 with the mist on the hills and the pipes of the patupaiarehe trying to misdirect you. The interweave of Māori storytelling feels respectful, though it would have been good to see a more thorough acknowledgements section as I am sure he will have spoken to local iwi Ngāi Tahu to ensure they were happy with his use of their stories.

This is a slim book of historical fiction based on a true story, which would be perfect for schools as the curriculum shifts to better include New Zealand history. Highly recommended.

Across the Risen Sea, by Bren MacDibble (Allen & Unwin)

Bren popped onto the scene in the first year of The Sapling, delivering an award-winning and explosive first book How to Bee, then following it up the following year with The Dog Runner. Both books are ecological in theme, and so is Across the Risen Sea.

In March this year (so about 80 million years ago), The Sapling published a reckoning by Elizabeth Kirkby-McLeod, which argued that it isn’t fair to pass on our despair, comparing and contrasting the hopefulness of How to Bee with the relative hopelessness of The Dog Runner. I loved both of these books and hadn’t seen what Elizabeth did in them, but I thought I would have a look at Across the Risen Sea from the perspective of offering hope to children, whatever your feeling is on this matter.

I thought I would have a look at Across the Risen Sea from the perspective of offering hope to children…

While I will explore this further, I’d like to say yes, this passes the hope test. The main character, Neoma, lives with the other kids on the Ockery Isles in Rusty Bus. They live in a community, parents apart from children to start with while their immunity builds, and the oldest person there is Marta – she is the one who remembers our world as it is now, before super storms saw the sea rise and flood the low-lying areas.

‘She remembers when clouds were jus’ white. She says the green is bacteria and it’s the way the earth tries to make things right and clean, and one day, when the earth is done with cleaning, the clouds will all be white as white once more.’

They are living as they usually do, sharing the jobs like fishing, trading, building, when along comes some people from a place called The Valley of the Sun. Marta understands their language, but doesn’t know why they cut down trees and create a tower with a red light on it, so it creates a feeling of unease among the villagers.

Neoma and her friend Jaguar decide to do something about it one night, and adventure ensues. Neoma is brave, wise, and up for anything; Jag is a bit less brave in the water, with a fear of sharks and crocs, but he steps up when it counts. The hope in this book comes from the care their parents and community show them, and the humanity the kids encounter on their adventures.

Neoma is brave, wise, and up for anything; Jag is a bit less brave in the water, with a fear of sharks and crocs, but he steps up when it counts.

Neoma ends up sailing across the risen sea, during which she acquires a croc who ends up on her journey with her thanks to being unable to untwine itself from a net. ‘You stuck yourself, you numbat!’ They meet Pirate Bradshaw (the most un-killable pirate you’ll ever meet) and her ship-girl Saleesi along the way, and there are many a giant shark following them around as Neoma steers her ma’s boat Licorice Stix through the ocean.

What she finds when she gets where she is headed is surprising, but not all unpleasant, and the end is a happy one, as the young girl schools some adults on what true democracy and care for all people looks like. ‘You call me wild, but we don’t treat anybody in our village in that way.’

…the end is a happy one, as the young girl schools some adults on what true democracy and care for all people looks like.

The tone of the book is that of a thrilling, if dangerous adventure, with some lessons to be learned by those who care to see them. I highly recommend it both for those who loved Bren’s first books, young and old, and for those who were too young for those books at the time they were published. It is probably the first of Bren’s books I will read with my anxious 9-year-old.

Enemy at the Gate, by Philippa Werry (Pipi Press)

Well done to Philippa for picking up the rights to this book, which was originally published by Scholastic, and republishing it at such a ripe time!

Poliomyelitis was the terror of the playground, and this ‘summer disease’ wreaked havoc on New Zealand children for months at a time several occasions in our history. The biggest of them were 1924–25, and 1937–38. This book is set in the latter period, and this heightens the fears held by the parents of the generation being threatened by this disease, which crippled and killed many young children.

This book is set in the latter period, and this heightens the fears held by the parents of the generation being threatened by this disease, which crippled and killed many young children.

Werry places the action with twelve-year-old Tom, who is the oldest boy in his family of five kids, with one older sister, two younger sisters and one younger brother. The book begins as he and his best mate Charlie throw a sandball on the beach at Lyall Bay at the another family’s dad, then have to scatter to another part of the beach for Tom to practise his running, with Charlie timing him.

There is nothing Tom loves better than to feel his legs sprinting, and he idolises Jack Lovelock for his Olympic achievements, hoping one day to attend the Olympics himself. He is looking forward to the summer holidays, when he can run and play all day with Charlie. Until the unthinkable happens.

First, the school is let out a week early for the long summer holidays, then the restrictions on outings come in. No movie theatres are open, and children are not allowed to travel outside their own regions. Sound familiar? It should do.

Tom has a tendency towards anxiety, something that isn’t frequently present in books for that age group. He develops mantras as a way of protecting his siblings from the dreaded disease: ‘Wiggle the toes on one foot, ten times. The other foot, ten times. Then I had to say the names of everyone in my family, five times over, in my head.’

He develops mantras as a way of protecting his siblings from the dreaded disease.

As they return late from the holidays, all seems to be well, but suddenly it strikes: someone in his family is struck with the disease (his sister Flo), and the whole family is quarantined for several weeks. They return to school eventually – only for school to be closed again a month later, with learning resuming via the daily newspaper, and the wireless.

‘Flo in isolation. Flo, who always liked having lots of people around, who hated being alone.’

Tom’s family isn’t rich enough to have a wireless, but he manages to do his lessons on the newspaper, and shares it with Charlie so he can do the same. He is academic, and the adults around him keep bewildering him with entreaties to go into law, or medicine.

The book as a whole takes you right back to Lyall Bay in the 1930s, with Paddy the Wanderer jumping on and off trams, the Coronation celebration for King George VI, and a worldwide obsession with the Dionne quintuplets. The only raw point I attempted to double-check was an assertion there were no Māori in Lyall Bay in the 1930s, and in fact there is no reference to any ethnic diversity beyond Welsh.

The book as a whole takes you right back to Lyall Bay in the 1930s, with Paddy the Wanderer jumping on and off trams…

As a compare and contrast, this would be a fascinating book for a school to buy for a class to study. There have been many times in our past that our movements have been restricted in the name of public health, and COVID-19 was just one of them. Here’s hoping there won’t be many more. Recommended for kids aged 10+.

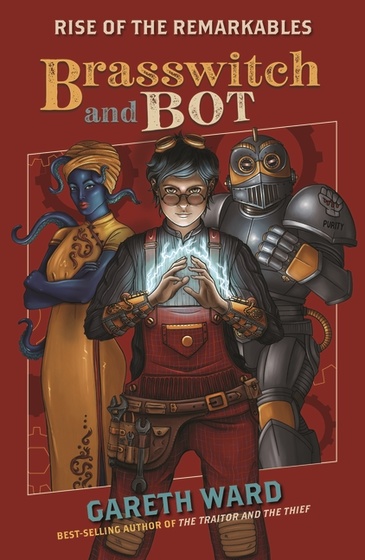

Brasswitch and Bot: Rise of the Remarkables, by Gareth Ward (Walker)

Rise of the Remarkables plunges you straight into the thick of the action, as our protagonist Wrench uses her powers to stop a crackle-tram accident, falling foul of the regulators and finding herself in Flemington’s electric chair faster than you can say, ‘What’s a crackle-tram again?’

We are firmly in Ward’s familiar world of steampunk adventures once again, but this time with a brand new series. No more traitor or thief, but plenty more magic, robots, monopeds, and remarkable folks affected by an overflow of evil magic called the Rupture causing ‘aberrations’ like Wrench, who is what they know as a brasswitch, and able to wield her magic over metal. This is useful in a steampunk world, but also highly suspicious, and many regulators / police disagree with allowing brasswitches and other aberrations to live.

We are firmly in Ward’s familiar world of steampunk adventures once again, but this time with a brand new series.

Wrench’s unfortunate visit to the electric chair doesn’t see her destroyed, as before she prevents her own death, Bot spirits her away to join the Thirteenth. Wrench is not all that happy, because as they speed away on a walker, Bot explains that he needs her help to open a metal coffin with a particularly vicious NIA (non-indigenous aberration) in it, later explaining she would be joining the regulators – the very group that Flemington who was about to fry her was part of.

This turns out to be the first of many such adventures, all told with Ward’s signature humour and skill, with plenty of high-stakes action and some great supporting characters: Plum, Octavia, Mr Grimthrope, and literal brain in the jar Master Tranter. As I know both Gareth and his wife Louise I couldn’t help imagining her exact intonation every time Wrench says, ‘Chuffing heck.’

As I know both Gareth and his wife Louise I couldn’t help imagining her exact intonation every time Wrench says, ‘Chuffing heck.’

Sharp dialogue is a particular skill of Ward’s, and he builds his world subtly through discussions between the key characters.

‘You were supposed to be learning magic.’

‘I am. When you catch fire, I can think of lemons and spit on your molten remains.’

‘You’ve changed,’ said Bot.

Wrench pressed her back flat against the pillar. A gout of flame shot past, inches from her chest.

‘Repetitive near-death experiences will do that to a girl.’

‘Don’t get me wrong. I like the new you. Much more how a Brasswitch should be.’

As the thaumagician Plum teaches Wrench (also known as Brasswitch) how to use other magic, she also grows in her own powers, sometimes with hilarious consequences. In the scene quoted from above, Wrench couldn’t think of any music other than Ring o’ Ring o’ Roses to direct a pipe organ to play in order to distract an NIA.

We discover, after a few suspicious incidents involving Flemington, that not only does he dislike ‘aberrations’ in the regulators force, he also has a particular problem with Wrench. But is he the only one working against her? The book concludes with plenty of space for further stories in the world of Brasswitch and Bot.

But is [Flemington] the only one working against [Wrench]? The book concludes with plenty of space for further stories in the world of Brasswitch and Bot.

I highly recommend this book for lovers of steampunk, or simply great world-building. It really feels like a step up from the previous two books, and I think this is over to Ward’s skills as a world-builder growing. I look forward to reading the rest of the series with my older boy. The recommendation on the back is 12+, but mature readers 10 and older would enjoy it. My main cause for caution is simply the level of violence, which can be quite extreme.

Brasswitch and Bot: Rise of the Remarkables

Written by Gareth Ward

Published by Walker Australia

RRP $22.99

Sarah Forster has worked in the New Zealand book industry for 15 years, in roles promoting Aotearoa’s best authors and books. She has a Diploma in Publishing from Whitireia Polytechnic, and a BA (Hons) in History and Philosophy from the University of Otago. She was born in Winton, grew up in Westport, and lives in Wellington. She was a judge of the New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults in 2017. Her day job is as a Senior Communications Advisor—Content for Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.