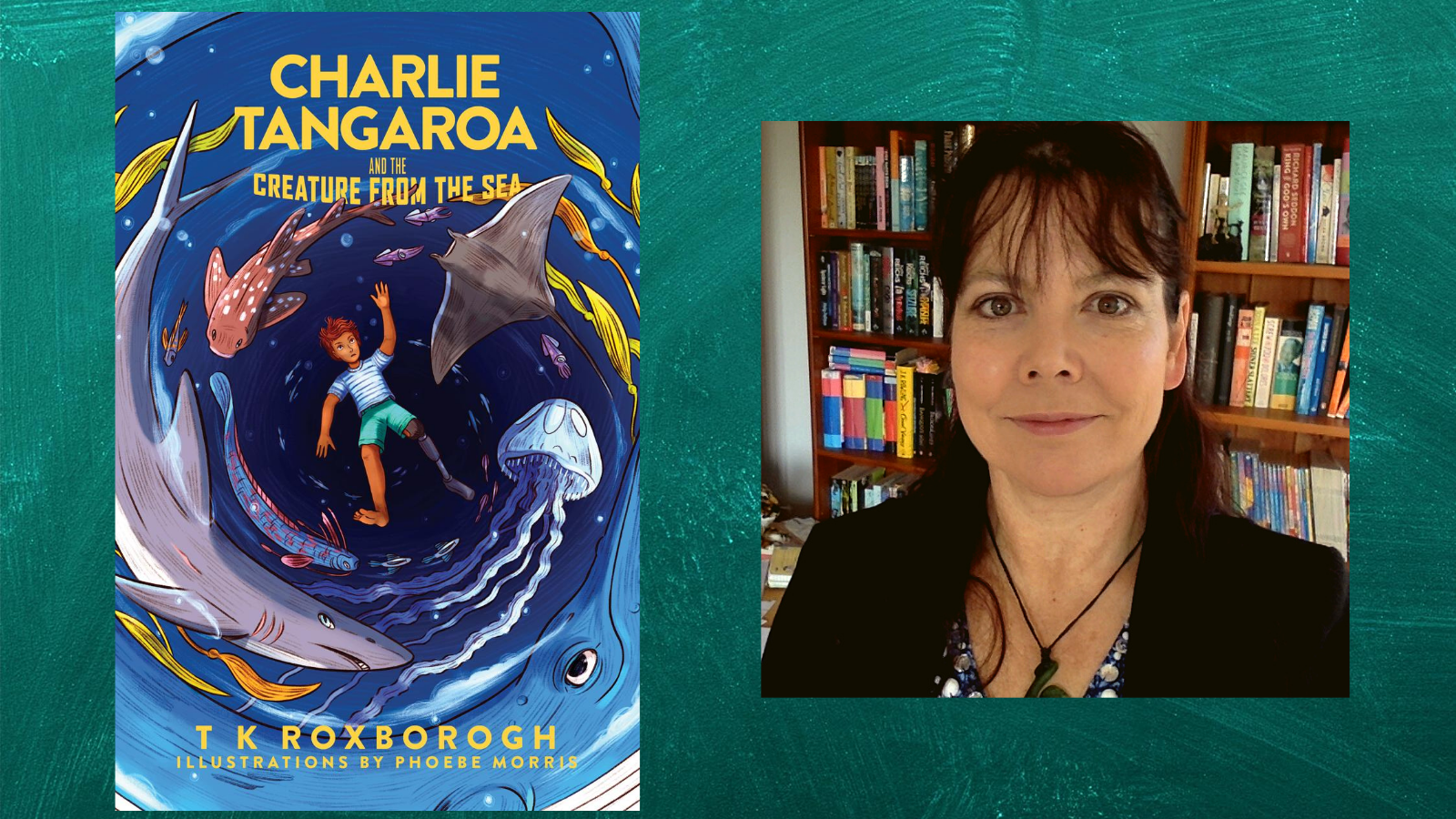

Here’s a new instalment of The Reckoning from writer and teacher Tania Roxborogh. She considers the use of Māori in classrooms and stories from here in Aotearoa and beyond – and she discusses her new book Charlie Tangaroa and the Creature From the Sea.

Ka taea koutou tēnei arokatenga te pānui i te reo Māori.

For the past decade, I’ve been learning te reo Māori. Before I went into my first lecture, I thought I knew a lot: I grew up in Northland, I was Māori. After one week, I realised I didn’t know squat. But I knew I wanted to know and that I wanted my students to know too. Why? Because of the stories. Because of the language. An official language dammit. Our kōrero, the codes and conventions of how we communicate them, the imagery tied to land and sea, anchor us, anchor our children to their world.

At the end of 2016, when I surveyed my classes about their feelings of my use of Māori words, phrases and ideas in the classroom, 85% of the respondents were negative about it. It was a gut punch to me and to our beautiful taonga.

It was a gut punch to me and to our beautiful taonga.

We make our children eat vegetables because we know they need them to thrive and grow. I ‘tricked’ my daughters into eating broccoli by telling them they were eating trees. That they were giants and eating trees was proof. What parent doesn’t use strategies to get their kids doing what is good for them? I had thought I was having the same success getting te ao Māori into the hungry minds of my students.

What texts and ideas a high school student is exposed to is almost exclusively dictated by their English teachers. It is my experience that kids often don’t know what they will like and, if presented properly (like enthusiastic plates of broccoli trees) students will willingly follow you down any literature and language path you go. This is why I have taught Shakespeare almost every year to every class brought before me. Shakespeare is the ‘giant’s fodder’ of English literature and all students deserve a taste.

. . . if presented properly, students will willingly follow you down any literature and language path you go.

But I don’t teach them in isolation. Like all cultures, Māori have a huge cache of stories and, despite many decades of being dominated by western European culture, there has been a resurgence of interest in and telling of these narratives. It is my joy and privilege –and responsibility – to bring to the young readers of New Zealand inside and out of my classes, a glimpse into this rich tapestry of language and story. My small part to mitigate over 150 years of colonisation and white-washing of our own narratives, is to champion both Shakespeare and Māori voices.

Holding onto the best of the literary traditions from our colonial past still matters a lot, because understanding our world is done best through stories, Māori and non-Māori. That moment when a student realises Shakespeare articulated better than any songwriter how she feels about her boyfriend; that moment when the class argues everyone is being too mean to King Lear and then starts to reflect on their own relationships with their fathers (and mothers) and how they could be better.

And that moment when a kid writes an essay and weaves in te reo Māori words because they are the better words – then they are bringing together the two worlds of New Zealand’s education system: the English one, built on Greek classical forms, linguistics, and the timelessness of Shakespeare, and the indigenous one that is filled with lessons and stories of things they see right out their window: the kauri, the pōhutukawa, the kūmara, the moana, the names and places with their own timeless narratives.

My journey with Charlie

Charlie’s opening comments at the start of Charlie Tangaroa and the Creature from the Sea came to me way back in 2008: ‘What would you do if you found a mermaid washed up on the beach?’ I wrote the first two chapters, and then everything seemed to shut down, as if the muse of the universe was saying, you’re not ready to write this story. It’s yours but you can’t have it yet. As the years went on, I began to realise that the story was more than I first thought and had something to do with my connection to East Coast (nō Ngāti Porou ōku tīpuna).

In 2014, Charlie’s voice returned and I travelled to the East Coast where I was ‘given’ the rest of the story. I think I needed to learn to read and write te reo Māori and to learn some of the history of our country before I was ‘allowed’ to write the story of Charlie and his adventures with the warring gods of Aotearoa New Zealand and the truths he discovers.

I think I needed to learn to read and write te reo Māori and to learn some of the history of our country…

The school I teach at is totally committed to students, their families, to learning, to well-being nestled tightly in our kōhanga. We are fledgling but so many of our staff endeavor to kōrero solely in Māori whenever we encounter each other in the playground or the staff room. It’s hard. But the kids see it. They see us value te reo me ngā tikanga. It continues to whakamana i tō tātou taonga. It allows our Māori students to grow taller and it encourages everyone to value this rich gift of language.

Late last year, I re-issued the survey. This time, only 15% of the students were negative. That’s an incredible shift. Our students look to us as their role models. They will value what we value and I believe the stories springing out of Aotearoa can be both shiny and new and at the same steeped in tikanga and tradition.

I believe the stories springing out of Aotearoa can be both shiny and new and at the same steeped in tikanga and tradition.

Let us go forward looking back, reaching for the novels, poems, graphic texts which reflect Aotearoa. Ground our rangatahi in the narratives of their own land as well as those from across the sea and down through time. Their lives will be richer for it. We must be their guides through the broccoli trees.

Editors’ note: The Reckoning is a regular column where children’s literature experts air their thoughts, views and grievances. They’re not necessarily the views of the editors or our readers. We would love to hear your response to any of The Reckonings – join in the discussion over on Facebook.

Tania Roxborogh

Tania (TK) Roxborogh, of Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Mutunga o Wharekauri, Scottish, German and Irish descent, is an award-winning author of more than thirty published works, both fiction and non-fiction. The first book in theCharlie Tangaroaseries, won the Wright Family Foundation Esther Glen Award for Junior Fiction and the Margaret Mahy Book of the Year at the 2021 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults.Taniais also a veteran educator, writing mentor, book reviewer and one of the judges for the 2025 Ockham Book Awards. She is currently working on a PhD researching ways to help teachers imbue the teaching of Shakespeare with mātauranga Māori.