How does a bookish child develop a love of reading in a household with few books? Libraries of course! Kelly Gardiner writes about the books from her childhood that inspired a love of reading and shaped her own writing.

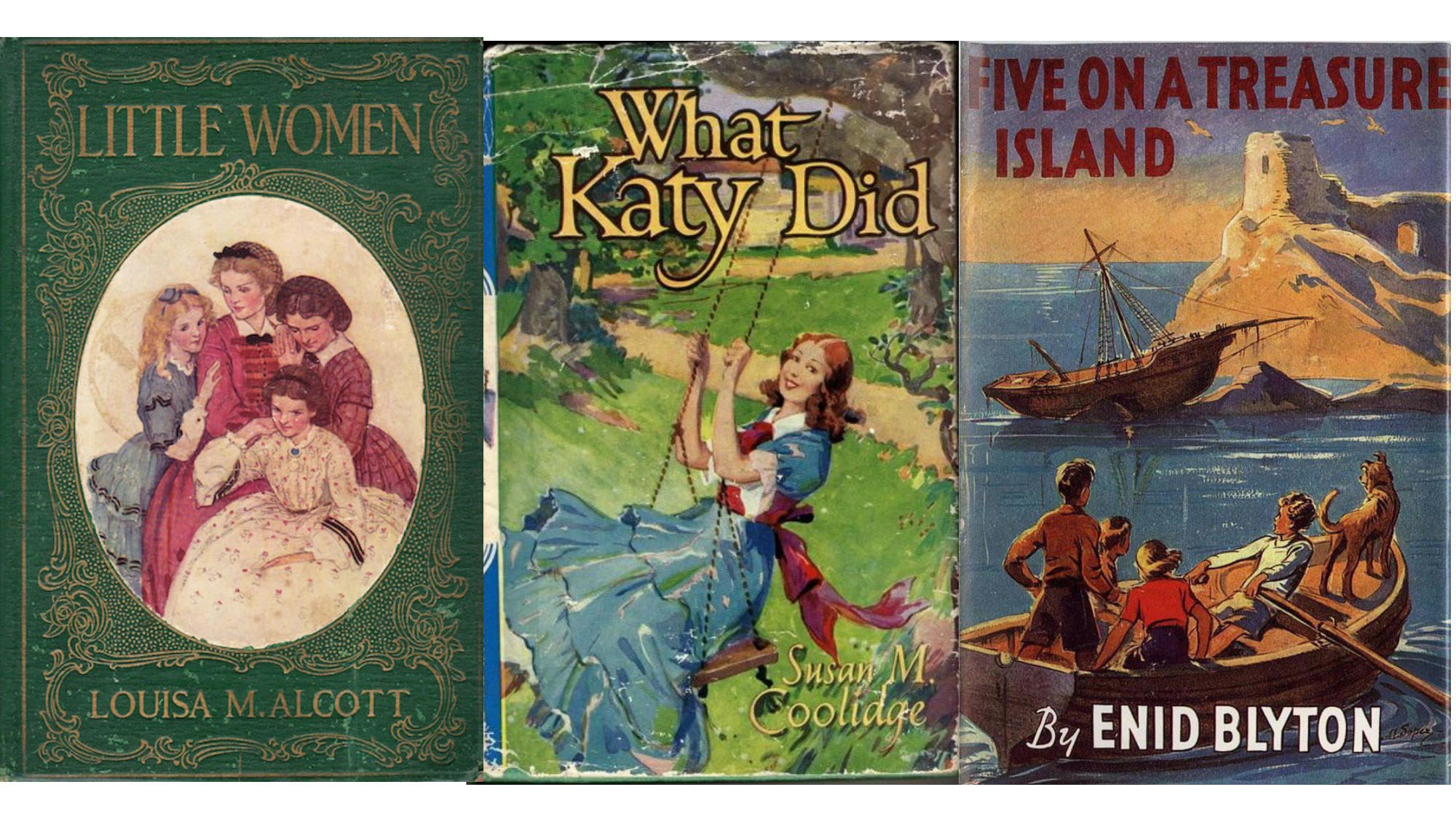

I come, somehow, from a bookish family without books. I’m not sure how it happened; my mum is a big reader, although there were few books in her house when she was growing up – Five on a Treasure Island, Little Women, What Katy Did. Books were expensive and money was scarce. But she had a public library nearby, and she used to visit there all the time. The story goes that on the day she got her drivers’ licence, the first place she wanted to drive was the library. So she borrowed my grandfather’s car and drove, all by herself, the whole 500 metres down the road to the library – and drove straight into the library. The library was undamaged although the car was a little dented.

A few years later, after I was born, we moved to the very edge of the city – Melbourne, where beyond our house was bush and orchards in which we kids could run wild. But no library. So I grew up with those same few books, now slightly tattered: Five on a Treasure Island, Little Women, What Katy Did. Until the magical day, when I was around eight, when the brand-new Nunawading Public Library opened, and Mum got to drive us there every week. It was there that I discovered the glory that was the Children’s Fiction, R-Z shelf.

Rosemary Sutcliff, Geoffrey Trease, Ronald Welch, Henry Treece. Vikings and Shakespearean actors and knights and Romans. Ivan Southall’s gripping adventures about kids like me in places like mine. Robert Louis Stevenson and his pirates. Leon Garfield wasn’t shelved in R-Z, obviously, but his books dwell in a special shelf of their own in my library heaven. I can still remember the feeling of standing there for hours, head on one side, reading the spines, deciding which treasures to take home with me.

I can still remember the feeling of standing there for hours, head on one side, reading the spines, deciding which treasures to take home with me.

This was the golden era of post-war historical fiction for children, and these were masters of the craft, especially Garfield, Sutcliff and Trease, who were thoughtful writers for young readers, testing the limits of historical knowledge, language, and world-building. I fell hard. I write what I write today because of them, and because I remember the feeling of reading them for the first time.

I learned a great deal from them about history and about writing, both back then and now, on re-reading. Sutcliff challenges young readers to engage with language and with landscape, and tries to create a sense of the ancient world view for a modern mind. (Margaret Mahy once told me she adored Sutcliff’s way with words.) Trease perfected the transparent voice in historical fiction, so the reader barely notices the narration, and it holds no anachronisms to throw you out of the story while he tries to capture the mental and moral frameworks of the eras in which his books are set. Garfield relishes the slang of, say, Regency London, and you learn to do the same. His book Devil in the Fog scared the living daylights out of me, and from him I learned that words on a page can make you feel real sensations in your body. All three of these writers thought a great deal about writing for children, believing it to be a serious and complex endeavour, and about writing the past, and their essays are well worth reading – for writers, teachers, and librarians.

… these writers thought a great deal about writing for children, believing it to be a serious and complex endeavour, and about writing the past, and their essays are well worth reading – for writers, teachers, and librarians.

Not all of those beloved childhood books stand the test of time. Styles have changed, and these books come from a very specific generation of middle-class white British writers. Some of them (especially Welch’s) are often racist and anti-Semitic, or flag-wavingly imperial. Trease was one of the first of his generation to consciously write girl protagonists in historical adventures, but even in those days, a kid who grew up with fictional tomboys: George, Jo March, and Katy knew these books needed a lot more girls in them. Some are simply not that good – the adventures are not very adventurous, characters thin, and the suspense pretty saggy, at least to my adult eyes now, after years of reading the many thrilling middle-grade and YA stories of recent years, and writing my own.

Not all of those beloved childhood books stand the test of time. Styles have changed, and these books come from a very specific generation of middle-class white British writers.

But these authors interest me, too, in engaging with their contemporary world through the lens of the past, without banging on about it. They had all survived the Second World War, either in the services or through the Blitz, and Sutcliff’s novels about the Roman invasion of Iron-Age Britain or the decades after the Romans left are all about how to live with war and destruction, and even, especially in Dawn Wind, how to live among ruins, as many children did. None of them shy away from depicting war and violence, and the better writers among them do not glorify it either. They recognized that young readers were either surviving or living in communities filled with survivors, and subtly drew on the past to give them hope.

And hope, after all, is one of the most important elements in writing for children and young adults – in any era.

Kelly Gardiner

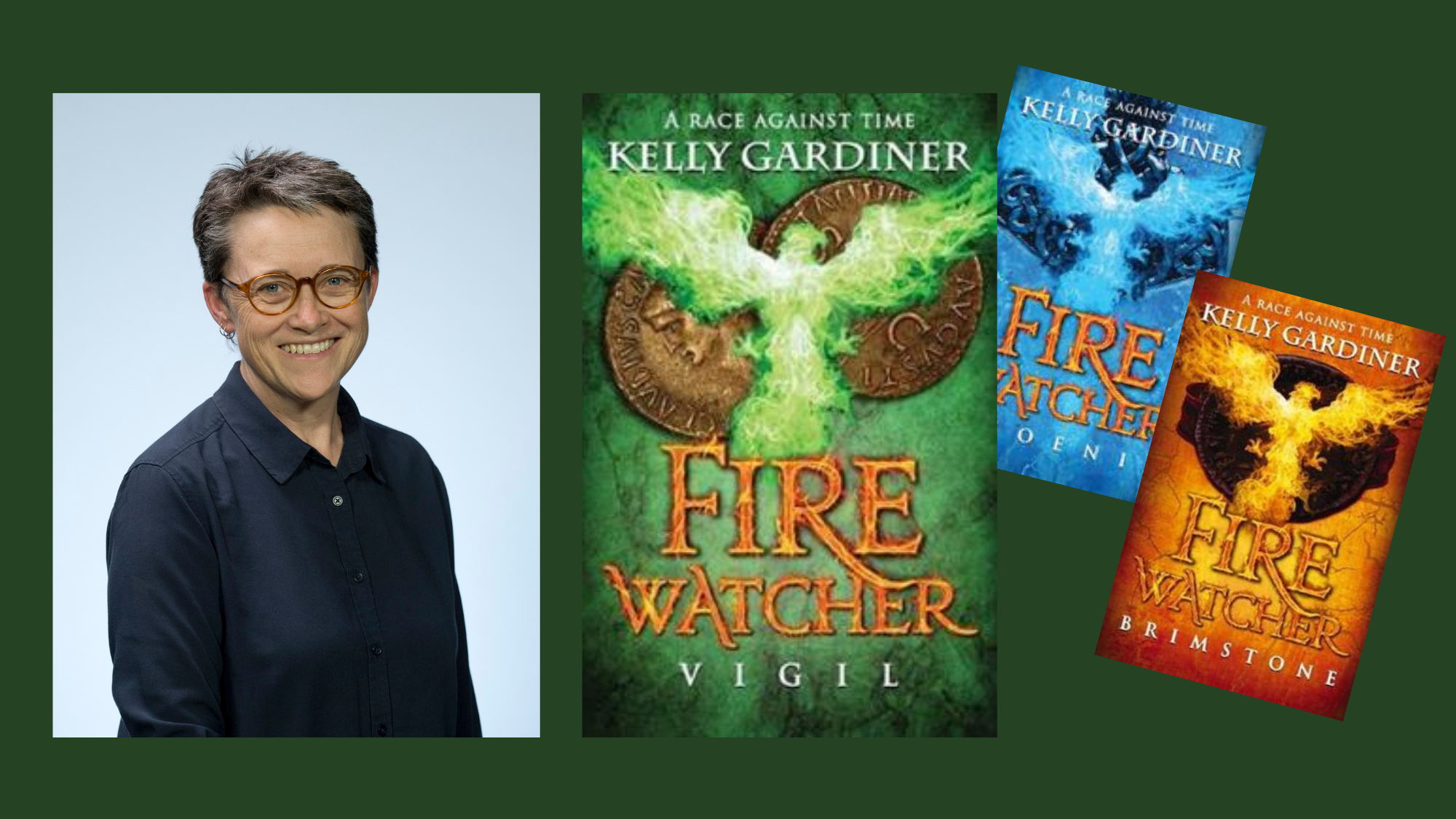

Kelly Gardiner’s new series is The Firewatcher Chronicles. Her books include 1917, shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Young People’s History Prize and Asher Award; Act of Faith and The Sultan’s Eyes; the Swashbuckler pirate trilogy; and Goddess, based on the life of Mademoiselle de Maupin. Kelly teaches writing at La Trobe University in Melbourne and (normally!) spends part of the year in Auckland.