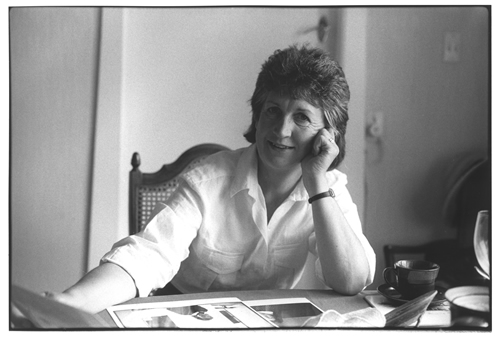

Dame Fiona Kidman is a legend of letters in Aotearoa. Among her many achievements and accolades, she’s been the recipient of the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement (2011), she’s won the top fiction prize in the country (This Mortal Boy in 2018) and as her title suggests, she was made a Dame Companion of the NZOM for services to literature in 1998. So we’re delighted to share with you this essay from Dame Fiona in which she takes us back to her younger years, where books were sometimes scarce but stories were always plentiful.

It was in World War Two that I became aware of books. Well, one book that I remember. Like so many of my contemporaries, I can tell you that the books we children read were from England, and England had the most massive paper shortage so, in fact, there were not many books at all. It was not that my mother didn’t read to me; she read me one precious book that was about baby chaffinches, over and again. I have no idea what it was called.

…the books we children read were from England, and England had the most massive paper shortage so, in fact, there were not many books at all.

At that time, during those war years, my mother and I lived on a farm in Waikato. We were refugees from Auckland, where we had lived in one dark room after another in boarding houses, while my father served in the Air Force. At some point, my mother became terrified that she would be called up to do war work because she had only one child, and she would have nowhere safe to leave me. My Scots grandparents and several of my mother’s siblings lived on the family farm in Morrinsville and we were shortly to join them. The dining room adjoined the kitchen and there was a long kauri table and a carved dresser against one wall.

My grandfather would sit at the head of the table in the mornings, while sun streamed in across the room. He would paint honey and butter on his porridge and then we would begin the morning ritual. ‘Tell me a story, Father,’ I would say, and he would transport me back into the world of the late nineteenth century, horse and buggy days, or riding around the sheep station of his youth, stopping to make fires to boil the billy – all those things and all those people who were no longer alive although the pictures of his parents and my great aunts and uncles peered down at us from the walls. My grandfather had Alzheimer’s, although there wasn’t a name for it then. It was called ‘losing one’s memory’. That’s all. But the past was a clear and ready presence.

…he would transport me back into the world of the late nineteenth century, horse and buggy days, or riding around the sheep station of his youth, stopping to make fires to boil the billy…

After breakfast, we would take to the hills, and the stories would continue. We would come back in time for lunch and an uncle would take me on the daily egg hunt, the cackle berry hunt he called it, and in the evening my mother and her sisters would carry on a ceaseless dialogue about what they had done, that day and always.

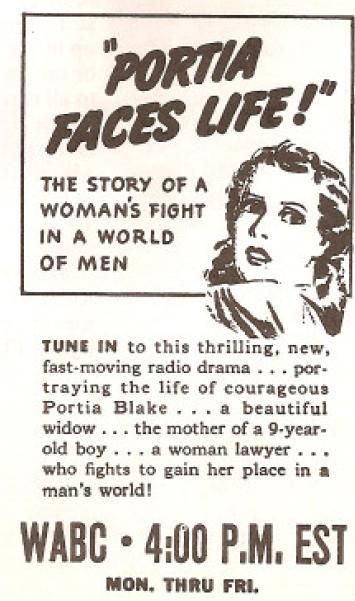

And this was how my life was. The life of a child where books, from circumstance, were scarce, but stories streamed out and around me every day. It was later, up north, that I began to understand just what a storyteller my mother was. I would follow her around while she picked orchard fruit for money, and we entered ceaseless dialogues in which we role-played the characters in radio serials – like Portia Faces Life and Dr Paul. These were not books, but they were stories, stories, stories. My father, the Irishman, who had been absent during the war, wasn’t too bad at them either, although they were often clouded by melancholy.

By then I had learned to read while a patient in a country hospital for some months. When I returned to school I had read a number of books from the hospital library: Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare, Warwick Deeping’s novels about people who had affairs, H. E Bates and The Darling Buds of May. I was not quite seven by then. Was any of this ‘suitable’? Well, no, of course not. But I knew that stuff was going on in the world and that there was much to learn about, lying in the future.

Was any of this ‘suitable’? Well, no, of course not. But I knew that stuff was going on in the world and that there was much to learn about, lying in the future.

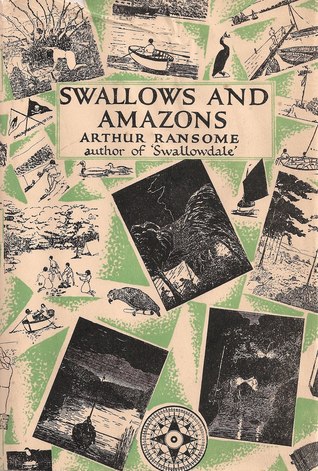

Meanwhile, some books intended to be read by children had begun to appear. Enid Blyton, Arthur Ransome, Noel Streatfeild. All about English children of course, just as fellow writers have commented. I liked the adventurousness of the kids in Swallows and Amazons. The rest floated past me; I knew I was never going to be a ballerina, or belong to a Famous Five. My father introduced me to Grey Owl and Sajo and her Beaver People. The disillusion about Grey Owl not being who he said he was didn’t set in until I was an adult (he was a British-born man whose real name was Archibald Belaney, who disguised himself as a First Nations man). And Rolf Boldrewood’s Robbery Under Arms, about bushrangers and their daring escapades and the trouble they got into. They were fodder for an already overheated imagination.

I was known by then as a weird kid, a bit of a loner who told mad stories. But over time the stories began to protect me. I became the entertainer, the girl who could spin improbable tales as the big kids, Māori and Pākehā, gathered around me on the spiky kikiyu grass playground. In return, they gave me their stories, real stories about New Zealand kids’ lives. I came to own them. They have never left me.

I was known by then as a weird kid, a bit of a loner who told mad stories. But over time the stories began to protect me.

By the time my own children came along I had trained as a librarian. I knew the proper stories that children should read. They got Dr Seuss, and Maurice Sendak and Roald Dahl, and fine stories they were too. Since then there have been another two generations. They get New Zealand books. Begin at the beginning. Patricia Grace, Margaret Mahy, Joy Cowley, Lani Wendt Young, David Hill. Of course.

I have never been able to write for kids although I’ve tried. I was hopelessly corrupted by too adult concepts in that far-away past. But narrative corruption has its own guilty pleasures. I count myself lucky for all the muck and mess of it..

Dame Fiona Kidman

Dame Fiona Kidman is a leading contemporary novelist, short story writer and poet. Much of her fiction is focused on how outsiders navigate their way in narrowly conformist society. She has published a large and exciting range of fiction and poetry, and has worked as a librarian, producer and critic. Kidman has won numerous awards, and she has been the recipient of fellowships, grants and other significant honours, as well as being a consistent advocate for New Zealand writers and literature.