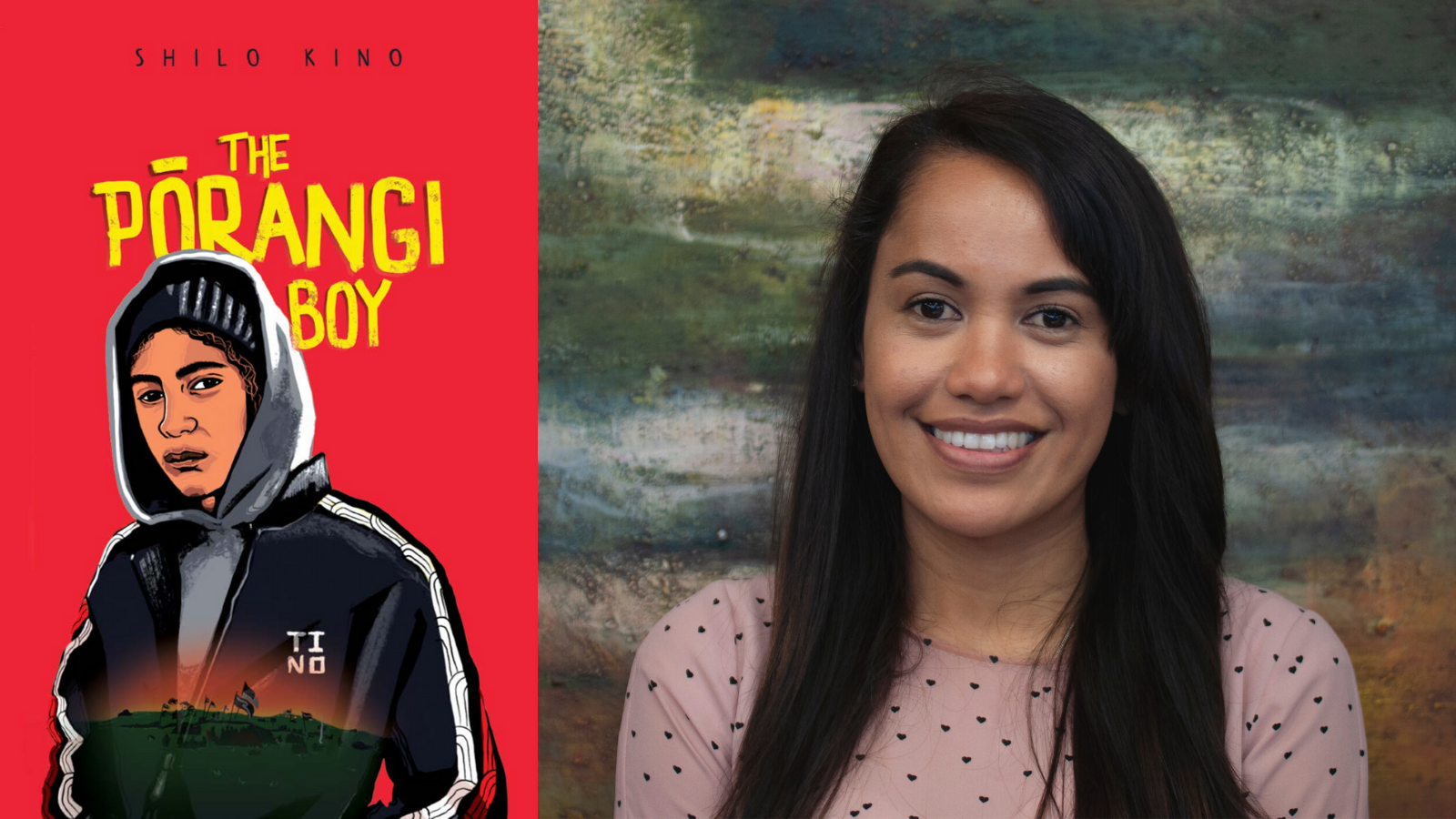

Cassie (J.C.) Hart (Kāi Tahu) met Shilo Kino (Ngāpuhi, Tainui) in July of 2018 as part of the Te Papa Tupu programme. They were gathered at their first mentorship hui with Huia and the Maori Literature Trust. Six nervous writers, waiting to meet their mentors…

At first, she seemed quiet, shy even, soft spoken and uncertain (though I think most of us were that day). Over the course of the mentorship though, I got to see more of the true Shilo—her strength, determination, delightful sense of humour, her values, her mana. And her love for Emperor Puffs (cream donuts).

It was a great honour to be asked to sit down and have a virtual chat with her about her debut release, The Pōrangi Boy, which releases on the 23rd of October 2020.

‘Twelve-year-old Niko lives in Pohe Bay, a small, rural town with a sacred hot spring—and a taniwha named Taukere. The government wants to build a prison over the home of the taniwha, and Niko’s grandfather is busy protesting. People call him pōrangi, crazy, but when he dies, it’s up to Niko to convince his community that the taniwha is real and stop the prison from being built. With help from his friend Wai, Niko must unite his whānau, honour his grandfather and stand up to his childhood bully.’

Let me set the scene for you – the fictional scene that is, because we’re writers in the time of COVID, so, why not?

I meet Shilo at a cafe situated in lush gardens. The years spent in China have left their mark on Shilo, and she seems to move through cultures with ease, though I know there was a lot of time and energy put into learning both the language and culture. There is a river burbling in the background, bringing the taniwha of Shilo’s book to mind, and I know that something is protecting this space we are in.

There is a river burbling in the background, bringing the taniwha of Shilo’s book to mind, and I know that something is protecting this space we are in.

I order a mocha, and Shilo has a peppermint tea. It has been far too long since we’ve seen each other so we catch up on the latest happenings. Tūī sing in the trees nearby, and I am grateful that there is no one else here at this early hour of the morning so that we can talk candidly.

We—the group who went through Te Papa Tupu with Shilo—are all extremely proud, and excited to see her book come out into the world, especially as hers is the first to release.

So, your book! How are you feeling about it all, e hoa?

I’ve been waiting for this day my whole life, it’s always been a dream of mine… but now that day has come and I’m like ahhh I’m not ready! I’m feeling super anxious about it all but I’m also looking forward to people reading it.

What was the inspiration behind this story? Why, out of all the potential stories in the world, was this the one you chose to write?

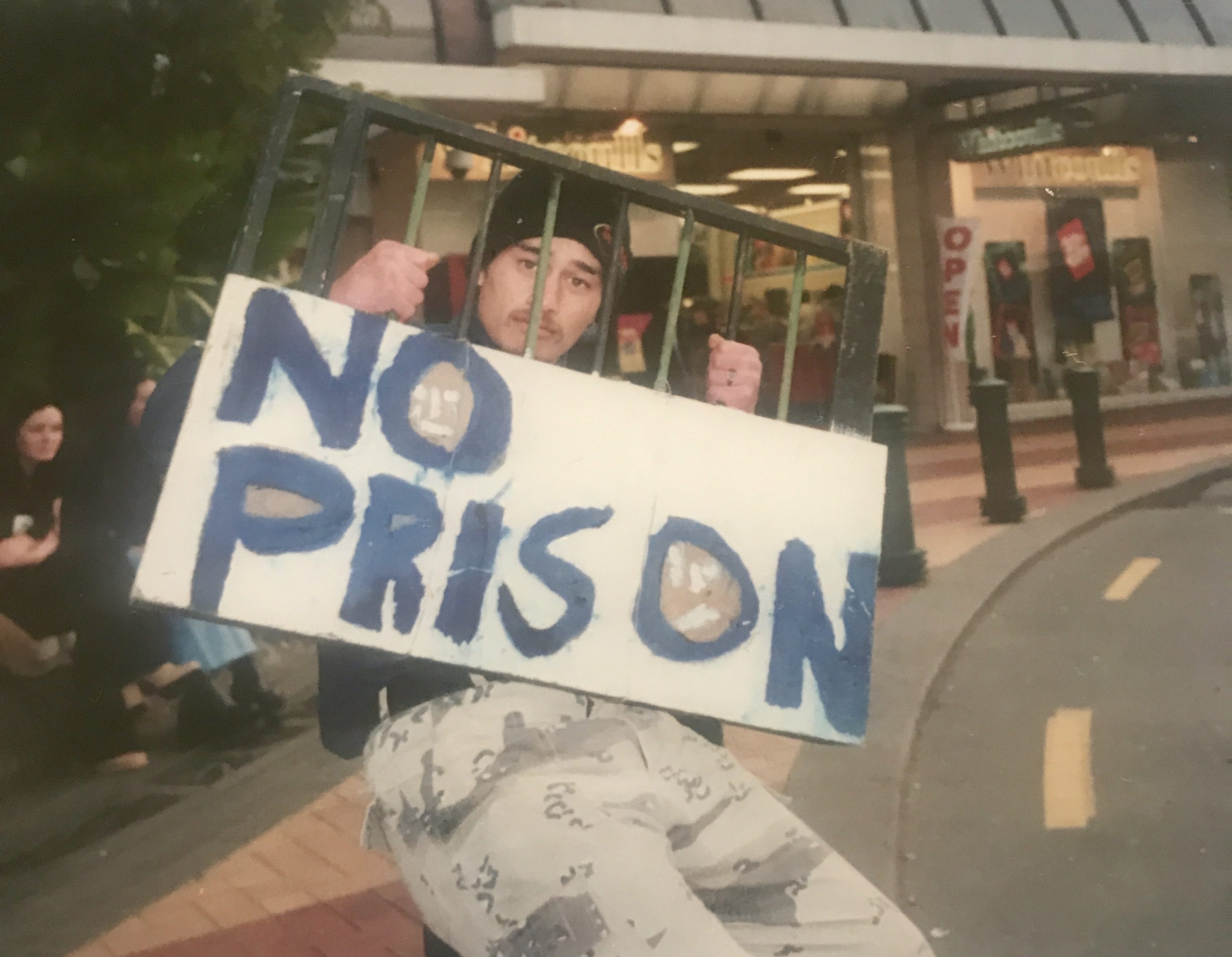

When I was younger, I remember reading about a town called Ngāwhā in a small community newspaper. The people were protesting against a prison being built on sacred land. I was fascinated by this because there was the mention of a taniwha as one of the reasons why they were protesting and I always thought the taniwha was a myth. I remember asking my Mum if the taniwha was real and she said yes and that she’d seen one when she was a kid. So, whenever I went swimming in rivers I used to look out for the taniwha and see if he was there!

Years later I did more research on Ngāwhā and realised there was so much more to this story. Ngāwhā locals fought for years to stop the Government spending $100 million on a prison on their land. Court battles, trips around the country to other iwi asking for help, multiple hīkoi, huis and occupying the land which resulted in arrests. The story of the Ngāwhā prison was never properly told in the media and I couldn’t understand why.

The story of the Ngāwhā prison was never properly told in the media and I couldn’t understand why.

I became frustrated and thought, why doesn’t our country know about this? Why aren’t our kids learning about this? Why didn’t I ever learn about all of this at school? And then I realized there are a million stories like Ngāwhā that haven’t been told, that Ngāwhā was just another example of the injustice that Māori and many other indigenous people around the world have faced since colonisation.

Like so many other Māori, I grew up so oblivious to our history. I had no idea about Bastion Point and had to learn about it as an adult. Our people have been protesting since the moment we were colonised but it has always been portrayed in a negative way in mainstream media. Māori are painted as angry and even crazy (hence the title of the book, The Pōrangi Boy).

Like so many other Māori, I grew up so oblivious to our history.I had no idea about Bastion Point and had to learn about it as an adult.

I thought maybe if I wrote a book and put two Māori kids at the centre of a protest, their perspective could teach us a lot. It would educate not just our younger generation but all New Zealanders about our history and the resilience of our people.

I certainly didn’t know about it before meeting you and hearing the story—it’s fascinating to see how your ideas unfolded. You went on your own hīkoi as part of your research. How did that trip influence your story?

I drove from Tauranga to Kaikohe, which was about an eight-hour drive, to meet Toi Maihi. She was one of the wahine who led the occupation and honestly meeting her was an absolute game changer. Toi had kept every newspaper clipping and photos of everything to do with the Ngāwhā prison occupation. I could feel the sadness, anger and hurt when she told me about what happened, and the four-year battle against the prison getting built. I also learnt more about why it was that the community opposed a prison.

I learnt that a Northland MP said he was ‘absolutely delighted’ when kuia and elderly were arrested outside the prison site for protesting. I was horrified when I read that in one of the articles Toi kept. I learnt about the travesty and injustice Māori faced trying to protect our taonga and sacred land. I realized this was a story of heartache and oppression and injustice, but after meeting Toi, it was also a story of hope and inspiration. I definitely wanted to capture that in the story.

I realized this was a story of heartache and oppression and injustice, but after meeting Toi, it was also a story of hope and inspiration.

She sounds like an amazing woman! Now, I’m always impressed by authors who can weave fact and fiction together to create a story—was there anything that helped guide you when making decisions around that?

I would say it was instinctive, but meeting Toi definitely helped weave in parts of the story. My job as a journalist helped as well, because I write non-fiction and tell people’s real-life stories for a living. I’m also a big fan of historical fiction so I drew inspiration from authors like Xin Ran, who writes a lot about Chinese history, woven into fiction. It’s like killing two birds with one stone really, you get an awesome story and you learn about the history as well.

What are you working on next?

I’m working on a young adult fiction book at the moment, it follows the lives of three teenagers in Auckland during the Black Lives Matter movement protests in the States. It explores how the BLM movement impacted the lives of three New Zealanders as well as exploring the topics of racism, identity, and belonging here in Aotearoa.

Sounds like it will be an excellent read! I’ll look forward to seeing it in bookstores in the future.

Thank you so much for taking the time to answer some questions about the creation of this pukapuka—and best of luck with the release of The Pōrangi Boy. For those reading at home, you can pre-order for the book here.

Now, how about another cuppa?

Cassie Hart

Cassie Hart (Kāi Tahu) is an award-winning author of speculative fiction. She lives nestled between Taranaki Maunga and the ocean, where she nurtures children, cats, and story ideas.