Susette Goldsmith reviews four fascinating books for older readers: think steampunk shenanigans, paranormal romance, celebrity secret identities and the grim realities of life as a member of a persecuted populace. As different as they may be, it turns out that they’ll all keep you at the edge of your seat…

The Clockill and the Thief by Gareth Ward (Walker Books)

Gareth Ward’s first novel The Traitor and The Thief won the 2016 Storylines Tessa Duder Award, the 2018 Sir Julius Vogel Award for Best Youth Novel and a Storylines Notable Book award. That’s a hard act to follow for any sequel but this second YA steampunk adventure, The Clockill and the Thief, does not disappoint. It’s a hefty (346 pages), rollicking tale of the struggle against evil, terrifying battles with high tech weapons and the ultimate triumph of skill and wits. Some characters die – or maybe they don’t – there’s page-by-page tension and just a smidgen of romance to leaven the mix.

Sin is an ex-illiterate street urchin and petty thief who has been recruited by the Covert Operations Group (COG) and is being trained as a spy. Assisted by sharpshooting brainbox Zonda Chubb, who has a weakness for cake and an idiosyncratic turn of phrase, fellow street-kid Stanley Nobbs, the monkey-man climber; and snobbish aristocratic frenemy Velvet Von Darque, Sin must outsmart sometime-traitor Eldritch Moons, the Kings Knights and Red Blades gangs, sky pirates, spider-legged ‘Chinasian’ Yan Shi and the dreaded man-monster Clockills with their clockwork brains.

COG’s mission is to stop ‘the war to end all wars’ in Europe and the four operatives have a mind-blowing array of industrial war machinery at their disposal. Of course, while this mission is going on, Sin has his own problems to sort out. Number one is the fact that he is dying, poisoned by his own blue blood and constrained by his need for regular transfusions and, naturally, the tendency for the precious vials of medicine to go missing. Problem number two is his need to know why his mother died to protect him, and his at times confusing relationship with his eccentric father Nimrod Barm.

Of course, while this mission is going on, Sin has his own problems to sort out.

Author Gareth Ward describes himself as a magician, hypnotist, storyteller, bookseller and author who lives in Hawke’s Bay. He is also a ‘fantabulous’ wordsmith who has a ‘gorgiferous’ way with words. Magician Magus Noir, Zulu warrior Sergeant Stonehart, pink-cheeked Claude Maggot and Captain Felicity Hawk populate the book along with the magnificent matron Madame Mékanique with her ‘thick Fromagian accent’. There’s a whiff of Harry Potter in The Clockill and the Thief and, in 2017, Ward told the NZ Herald that the brilliance of the Potter series had been an inspiration for him. But that admission takes nothing away from the sheer enjoyment Ward brings to his readers through his own distinctive style. He says he hasn’t finished with Sin and company and there might be another couple of books in the series. An exciting prospect? ‘Absolutamon’.

How to Lose A Rockstar, by Maureen Crisp (Marmac Media)

Tressa has a problem. She wants to be ‘a normal kid in a cottage with a dog, in a normal family and go to school’. Instead, she’s a very rich Irish kid who lives in a manor house with her rockstar father Paul, camera-toting brother Paddy, diet-obsessed model and stepmother Sancia, twin stepsiblings (who never really make an appearance in the book), and a crew of household staff and bodyguards. And that’s not her only complication.

Ever since Tressa was kidnapped by fans of her father’s band, leading to her mother’s death while rescuing her, she’s suffered anxiety and panic attacks and never leaves home by herself. To make matters worse, she and Paddy are travelling to New Zealand with her father’s band where she’s arranged meet up with her best friend Sonnie, found online… who thinks Tressa is ‘normal’. If Sonnie and her family – and, equally tricky, the press and the band’s Kiwi fans – recognise Paul, Tressa will be revealed as a liar and deprived of her only true friend. So, how to lose a rockstar…?

Sonnie Blair lives in Wellington with her hotel chef father, her overworked teacher mother, and her brother Craig – an obsessive fan of Tressa’s father’s band. She lives a ‘normal’ life and can’t wait to meet her friend. But right from their meeting at the airport it seems there’s something odd about Tressa and Sonnie is determined to find out what it is.

This is a high-octane romp of a novel set firmly in Wellington. Sonnie and Tressa and her family intend to spend a week in the city incognito, and the plot unravels at the Central Library (the café), Te Papa (the earthquake house), Lambton Quay (a menswear shop), Cuba Street (retro shops) and the Vivian Street tattoo museum (‘It’s not real. I’m too young. It washes off.’). There’s a ride on the ferry to the South Island and a plane trip back, there’s a great deal of money spent by the Irish visitors and Peter Jackson has a cameo role.

This is a high-octane romp of a novel set firmly in Wellington.

But there are a few glitches in the text, which closer editing would have sorted. Sometimes the transition from one family’s concerns to the other is confusing and the dialogue is clumsy on occasion, but the fast pace of the book means these are barely noticed. This is a YA novel to read in one sitting and pass on to a friend who enjoys urban adventure stories and can suspend belief for 236 pages in favour of fun. It’s a story of families and friendship, courage and compassion as well. Tressa’s anxiety is skilfully described and the support of her family and Sonnie is heart-warming. In the end, everything works out as it should.

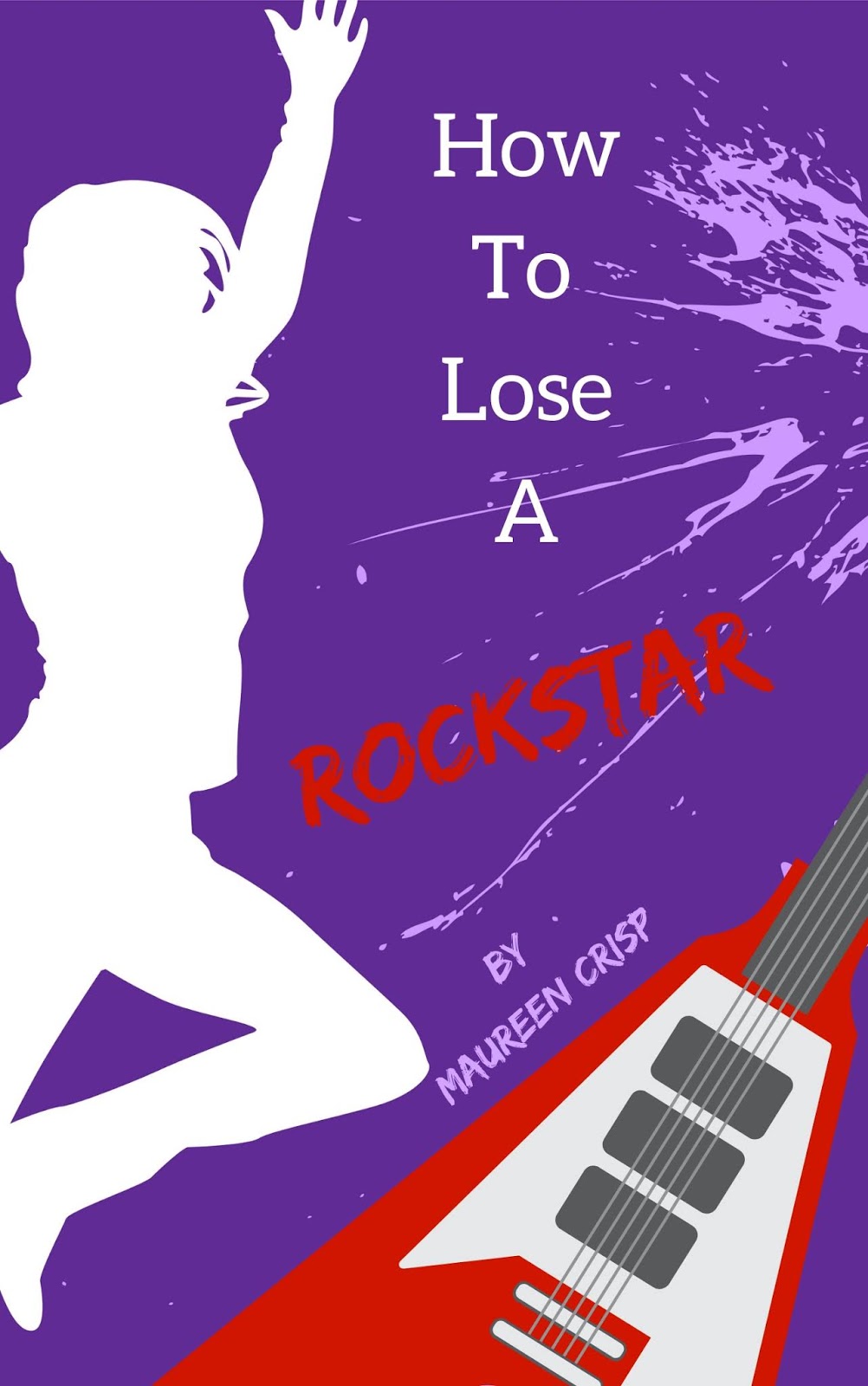

I Am Daniel Tahi, by Lani Wendt Young (OneTree House)

Daniel Tahi is young, smart and, as illustrated by the book’s cover, a ‘chunk hunk’. He’s the head prefect of a prestigious Samoan school, captain of its first fifteen and noted by international talent scouts, and he’s heading to win the science trophy, mathematics prize, national debate award and take out best all-round achiever. In his spare time, he runs a welding workshop. That’s the first-page prologue of I am Daniel Tahi. Good to get it all out of the way. Oh, did I mention that he’s also the apple of his grandmother Mama’s eye?

I am Daniel Tahi is part of Lani Wendt Young’s hugely popular Telesā YA fantasy romance series written for Pasifika teenagers and ‘for my 16-year-old self’. It slips in after The Covenant Keeper and When Water Burns as a prequel to The Bone Bearer. This is Daniel’s story told in his teenage voice. In the two-and-a-bit-page chapter one we discover that he sometimes wishes he had never met Leila, the star of the series. Before her, he grumbles, ‘I knew who I was. Where I was going. The path I walked had a sure foundation. Now? I see that the world I once knew – veiled many secrets.’ Of course, readers know most of the secrets and recognise Daniel’s predicament, assuming they have already read The Covenant Keeper – which is essential to understand what’s going on.

The action begins. A new girl (Leila) arrives at Samoa College (SamCo). Daniel thinks of her as #AngryGirl. They clash, he determines to make her smile, she resists, they meet by accident one night at a forest pool, he ‘rescues’ her, she cries, they talk. They have things in common – both have lost their parents. They like the same music. And they fall in love. Daniel gets on with life but is highly distracted by Leila’s presence and consumed by teenage angst. He may not notice the mystery surrounding her but the reader does. Why was Leila thrashing around in the water when it wasn’t very deep? Why did her rugby brawl attacker fall back from her, hands to face and screaming in agony? Why does she faint in the hallway at school? Why does Mama tell him to break off the friendship with Leila before it’s too late?

They clash, he determines to make her smile, she resists, they meet by accident one night at a forest pool, he ‘rescues’ her, she cries, they talk.

Will he? Won’t he? Should he? Shouldn’t he? Daniel agonises and we’re halfway through the book before finally they kiss – and it’s some kiss. ‘And then, the girl who has set me on fire with a kiss – explodes and bursts into flames. Literally. And my understanding of the world and how it’s meant to be, goes up in smoke.’ The reader is confused too. Leila’s mother Nafanua, it appears, is alive but doesn’t appear until late in the book. An American scientist cruises into the story in a red Ford truck, is mysteriously poisoned, recovers and disappears from the plot.

Then, with only twenty-five pages to go, three ‘very angry Telesā spirit women’ arrive in a silver Porsche Panamera hybrid to deal with Daniel and unleash their power. This is confusing, mesmeric and the whole point of the book. These are the spirit goddesses of the underworld inspired by Pacific mythology and gifted with the elemental powers of air, water and fire. There are blinding flashes, cannonballs of wind, sandalled feet with red nail polish and diamante toe rings, knives, skin tight dresses and fireballs of energy. ‘This is not some Women’s Komiti sisterhood that weaves mats and inspects gardens for rubbish’, Daniel notes. He’s an attractive character – charming, sensual, respectful, angry and often very funny. It’s good to know he survives for the next book of the series.

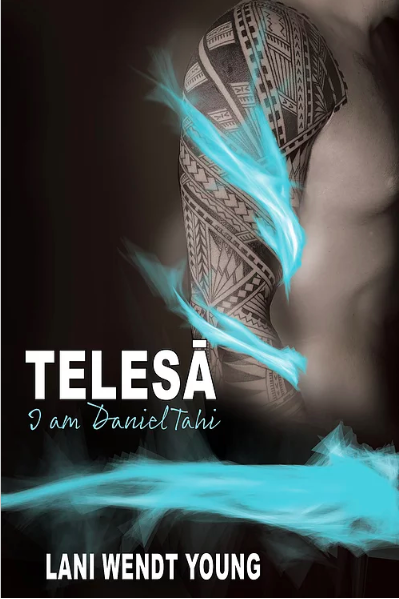

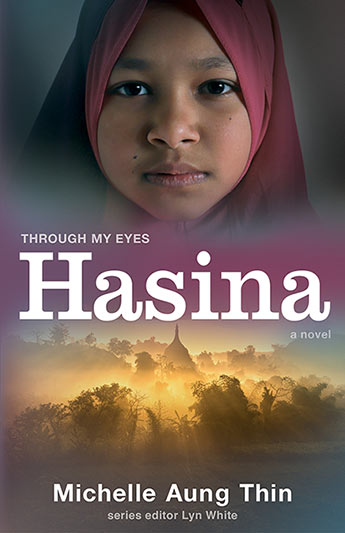

Hasina, by Michelle Aung Thin (Allen & Unwin)

Champion YA writer and reviewer David Hill wrote in New Zealand Review of Books that the establishment of YA fiction and non-fiction has allowed writers to ‘develop narratives, topics, characters, relationships, language, which had previously sprawled unsatisfactorily between children’s and adults’ books … It’s offered fresh, relevant material’.

Never more so, I suspect, than in the YA novel series Through My Eyes, which tells the stories of individual teenagers who live in conflict zones. Shahana (Kashmir), Amina (Somalia), Naveed (Afghanistan), Emilio (Mexico), Malini (Sri Lanka), Zafir (Syria) and, most recently, Hasina (Myanmar). The events are adult – conflict and cruelty, deprivation and despair – alongside universal concerns of adolescence – emerging self-identity and growing awareness of the tragedy and frustrations of life. At the base of it all is hope for peace.

Fourteen-year-old Hasina lives in a village in Rakhine State with her parents Nurzimal and Ibrahim, her six-year-old brother Araf, their thirteen-year-old cousin Ghadiya, Aunt Rukiah and grandmother Asmah. The children run from the ‘bird-like creatures’ that swoop over their makeshift home-school yard. Araf playfully calls them ‘heliwopters’, but Asmar, Ghadiya and Aunt Rukiah, recognise the sign of further violence.

Hasina’s family are Rohingya Muslims, an ethnic group persecuted for generations. Ibrahim makes a modest living selling shampoo, biscuits, toys and tea from the family’s stall in the bazaar; Nurzimal looks after the house and the family’s paddy field. It’s four years since Hasina went to the government school: rising fees forced Rohingya families out of the education system and the children study at home. Hasina wears a numal (headscarf) in public and keeps her head down. It’s a precarious balance in Myanmar. ‘If there are over one hundred and thirty-five ethnic groups in Myanmar, and many religions, then what happens if we all fight each other?’ Ibrahim asks Hasina. ‘We simply want the rights of full citizens. Medicine for your grandmother. School for you and Araf.’

It’s a precarious balance in Myanmar. ‘If there are over one hundred and thirty-five ethnic groups in Myanmar, and many religions, then what happens if we all fight each other?’

Men come at night in trucks and helicopters and set fire to the village, so Ibrahim orders the children to flee to the hills. Terrified, the children hide for five days then return to their burnt-out home. Only Asmah is there – too old and weak to escape with the rest of the family. Dead bodies float down the river, soldiers patrol the bazaar, food is scarce, and more men arrive to build a non-Rohingya town on the village site. Issues other than day-to-day survival are examined carefully and sensitively. While Hasina questions Nurzimal’s favouring of Araf and the rules her mother imposes on her as a Muslim girl, and although she abandons her numal now to avoid attracting attention, she still cannot enlist her friend Isak’s help to harvest the rice. ‘She would like to ask him. But a girl asking a boy … Some things she can’t bring herself to do.’

An orphaned Mro child joins Hasina’s remnant family despite knowing that her own people have been killed by Rohingya insurgents. Hasina is confronted with child trafficking and profiteering of medical and food aid supplies. There’s much for the reader to learn through Hasina’s story, a map of Myanmar, an author’s note; a Rohingya history timeline; a glossary of Bengali, Mro, Rohingya, Shan and Urdu terms and a list of web sites for more information.

The plight of the Rohingya people is a real and tragic contemporary issue and this is a serious contemporary novel. However, there is some hope – a telephone reunion with her parents who are at a refugee camp in Bangladesh. ‘She feels as if the Hasina who has had to defend her family at such great cost has been rejoined by Hasina, the girl who loves soccer and geometry and a boy with a crinkly smile. And her heart, bent and broken, is a little closer to whole again.’

Susette Goldsmith

Dr. Susette Goldsmith is a writer and editor of non-fiction, a natural heritage nerd, a compulsive and enthusiastic reader of anything that is well written and best friend of a curly-coated retriever called Plum.