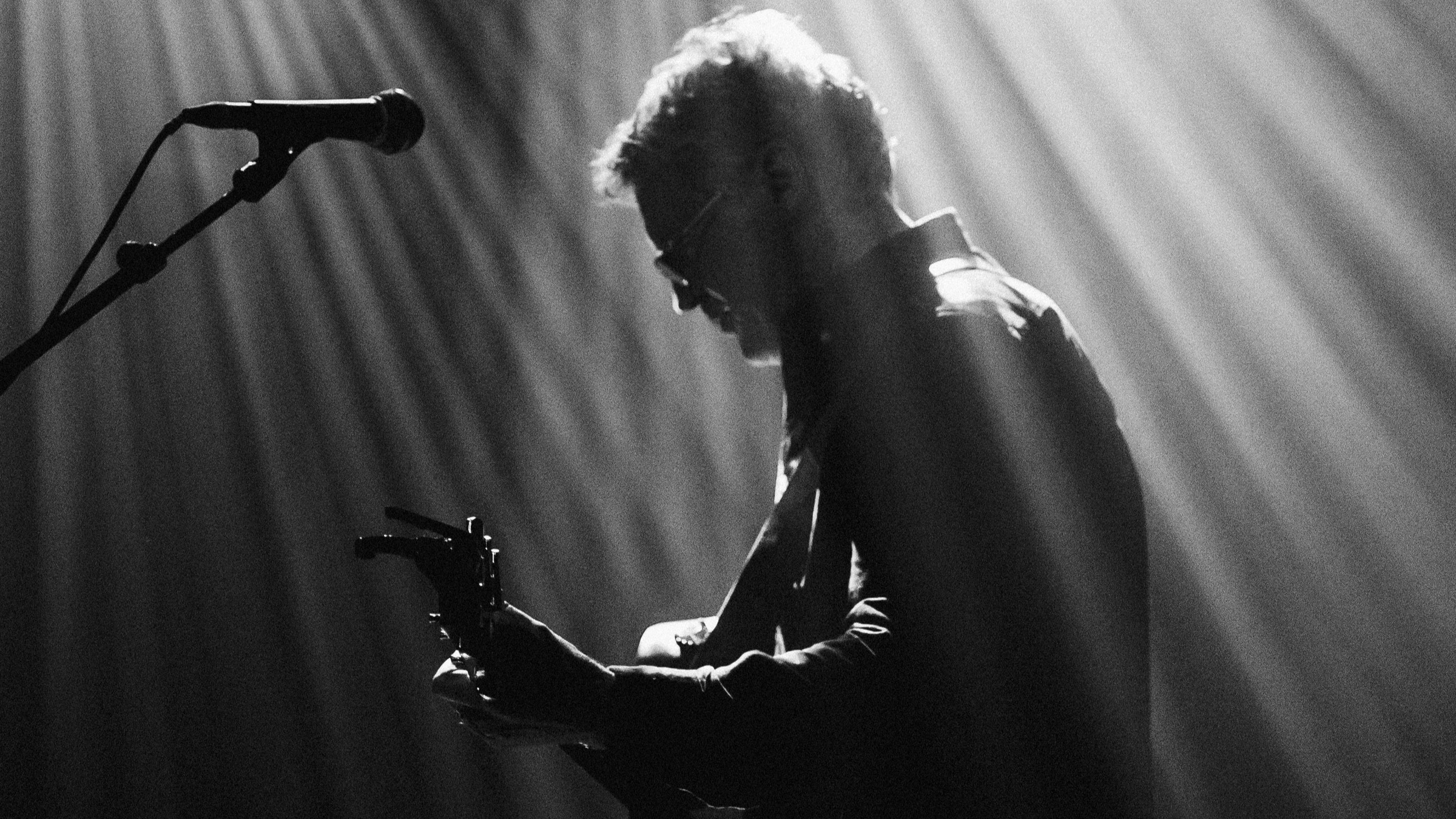

Don McGlashan’s love of words and ideas is evident in all his music. Today he tells us about throwing a picture book at the wall, wagging school for novel-reading, and the other ways books have formed him as a reader and writer.

Here’s one of my first memories: I’m awake too early for the rest of the family, (which happens a lot); unable to sleep, watching the lights move up the red curtains in my room as cars bounce over the dip where the creek crosses all our roads (named, I will later learn, after important British battles: Waterloo, Nile, Corunna), at right-angles.

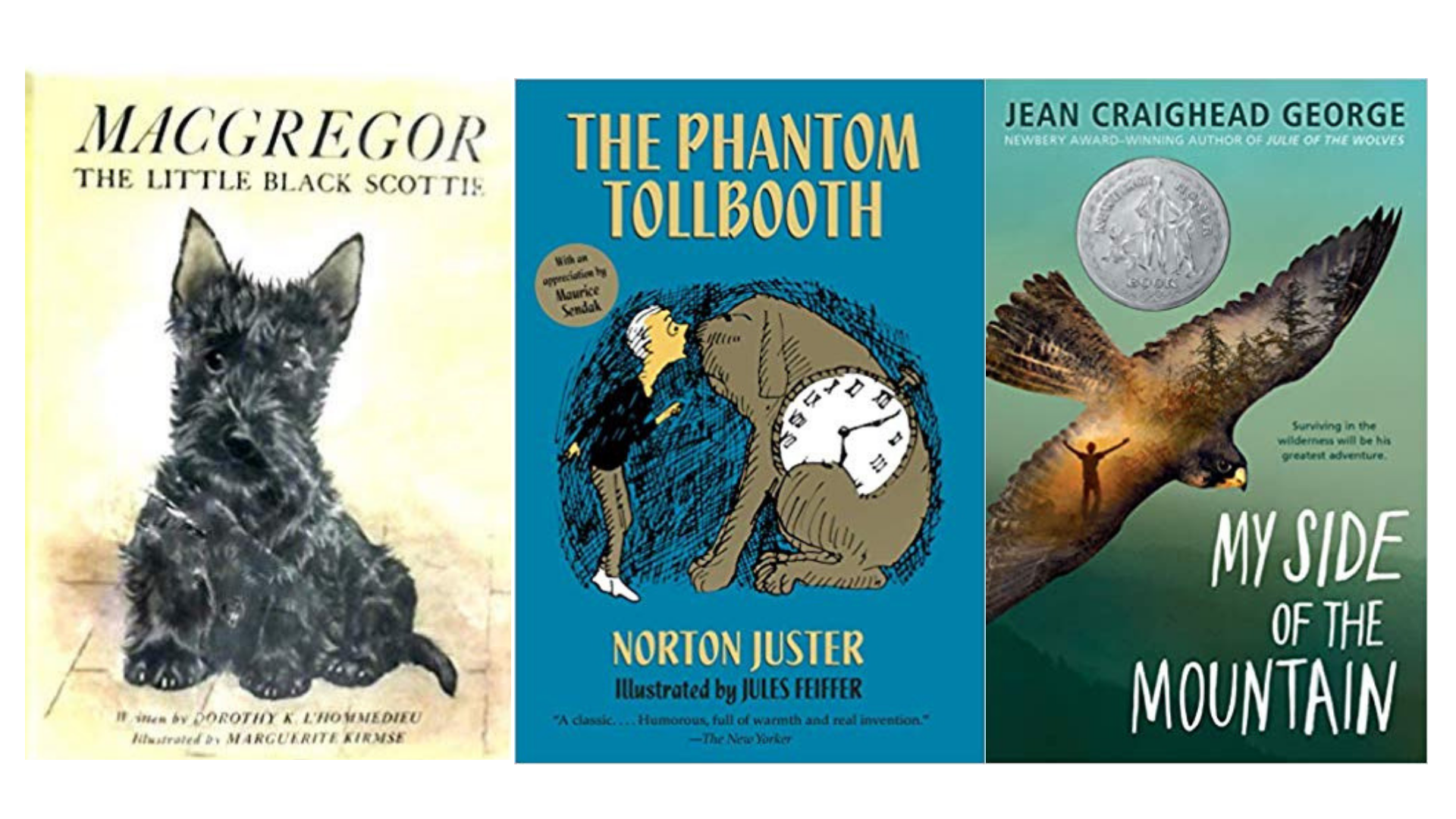

Then gradually, as the light comes up and I can see more, but it’s still too early to wake anyone, I stand up at the head of my bed and read the titles of a set of books by the oddly-named Dorothy K L’Hommedieu, about MacGregor, the Scottish Terrier. They are thin, tall books, with yellow paper covers, some a bit worn from being well-loved by my older brother and sister, and the band of sunlight falling on them, angling through the gap in the curtains, has dust motes dancing in it. I know the books have lots of words in them; far too many for me to read, but I can sound out the titles and the author’s exotic name, and when I quietly repeat those magic words I feel like an explorer unfolding the map of a new territory, that pretty soon I’ll be able to journey into.

My love affair with books almost didn’t start. My parents tried to read me Dr Seuss’s Horton Hatches The Egg when I was about three, and my fury over the injustice of it (credulous Horton is tricked into egg-minding by the feckless Maisie Bird, who flies to Florida and never comes back) became part of family folklore. The dent in the living room wall where I threw the book was visible for years, and older siblings would point it out to their friends as evidence that their little brother was a bit strange.

My parents tried to read me Dr Seuss’s Horton Hatches The Egg when I was about three, and my fury over the injustice of it became part of family folklore.

Now that I think of it, it’s possible that the cruelty at the heart of some of Dr Seuss’s books – Horton being an example – set me up well for working with my old friend Harry Sinclair on Kiri and Lou. It’s good to be making something for kids that isn’t like that; something that’s essentially optimistic and peaceful; a respite from the cyber-frenzied world that we’ve brought them into.In time, I decided to overlook Horton’s exploitation and came to love everything about books: the feel of their covers; the excitement of their potential; the knowledge that everything they contained was waiting for me, in my school bag, or on the table by my bed. I devoured the Moomintroll series by Tove Jansson, and then all the CS Lewis Narnia books, thrilling to the heft of the story-telling; oblivious to the Christian xenophobia lurking in the corners.

My parents signed me onto Ashton Scholastic. I imagined I was part of a special elite group of children nation-wide who were singled out to receive a package of books in the mail every month. I would go out to the letterbox several days early just in case, and look up and down the street, triumphantly aware that no other local children were waiting for a delivery.

At about age seven, I nagged our Standard 3 teacher into reading the class The Phantom Toll Booth, by Norton Juster, which I had just read and adored. Neither she, nor the class, shared my enthusiasm; they just thought it was weird. She got about a half a chapter in before abandoning it, and the class breathed a sigh of relief, looking at me suspiciously. I still give that book to specially-selected friends’ children. It’s superb, and in terms of sheer invention, it can give modern parallel-universe TV shows like Rick & Morty a good run for their money, I reckon. I also occasionally meet adults who were children in that class, and they still look at me suspiciously.

I think Ashton Scholastic must have sent me a book called My Side Of the Mountain, by Jean Craighead George, about a kid who survives a winter and summer on his own in the wilderness in Upstate New York.

I remember being utterly carried away by the boy’s predicament. Scared to turn each page lest something terrible happen to him. It’s amazing the way books open portals in you that stay open for the rest of your life. When I was first introduced about 10 years ago to the great American nature writer Annie Dillard, I felt some of that same cold, fierce rush of joy that I’d felt reading My Side Of The Mountain as a child. It was like the writer was staring at the very bones and sinews of the world, and turning to me, saying, “Here, you come and look too.” And when I saw the film “Leave No Trace” recently – starring my friend Miranda Harcourt’s wonderful daughter Thomasin – it, too, took me straight back to being enthralled by My Side Of The Mountain all those years ago, with its evocation of both the fear and the quiet exhilaration of survival in the woods.

I powered through the Alan Garner fantasy books: gutsy, frightening tales where Old Stories sit beneath the land, Awaiting their Time. I read The Hobbit, and eventually (in early high school) The Lord Of The Rings trilogy – staying home from school when important battles and journeys were taking place; lying on the orange Bremworth in the TV room, a little dizzy from sneaking gin from my parents’ cupboard, gradually wriggling with the book across the floor to stay in the shifting parallelogram of sunlight from the window, looking up pale and dazed when other family members came home – trying to remember what sort of sickness I’d used as an excuse that morning.

At Westlake Boys High School I was one of a small group of lame-asses who couldn’t talk with any authority about rugby or cars, but we read a lot. A friend introduced me to Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy, and, for a while, everything: school work, music, sailing – came a distant second to wandering with Titus, Steerpike and Fuschia through the castle’s labyrinths; reading a couple of pages at a time, then re-reading, more slowly, to savour the dense, detailed descriptions.

Why do I love books?

Books take you out of the familiar sights, sounds and smells of your world, and drop you into other worlds; especially when you’re a child, and your skin’s still porous enough to soak up new things.

Books stand alongside you; when you’re reading a book you’re not alone.

Books give you power. They feed and water your inner life, so that you can better withstand droughts and storms on the outside.

Books give you power. They feed and water your inner life, so that you can better withstand droughts and storms on the outside.

Books give you hope. If we encourage our kids to read actual books, not just tweets and memes, we can have more hope for the future. We’re going to need people in the future to write the letters, stand for office, and make the laws that will protect our species from harming itself and the planet. I’m convinced that the kids who will grow up to be those people are the ones that are reading a lot of books right now.

Don McGlashan

Don McGlashan is a singer, songwriter and composer. He was in From Scratch, Blam Blam Blam, The Front Lawn and The Mutton Birds. Now he makes albums and performs under his own name, and is part of the team that’s making the kids’ TV series Kiri and Lou.