Matariki has been celebrated in several picture books in recent years, but broadcaster Miriama Kamo’s new book, The Stolen Stars of Matariki, is the first to feature nine, not seven stars. Kristin Smith caught up with Miriama to hear how the book came about.

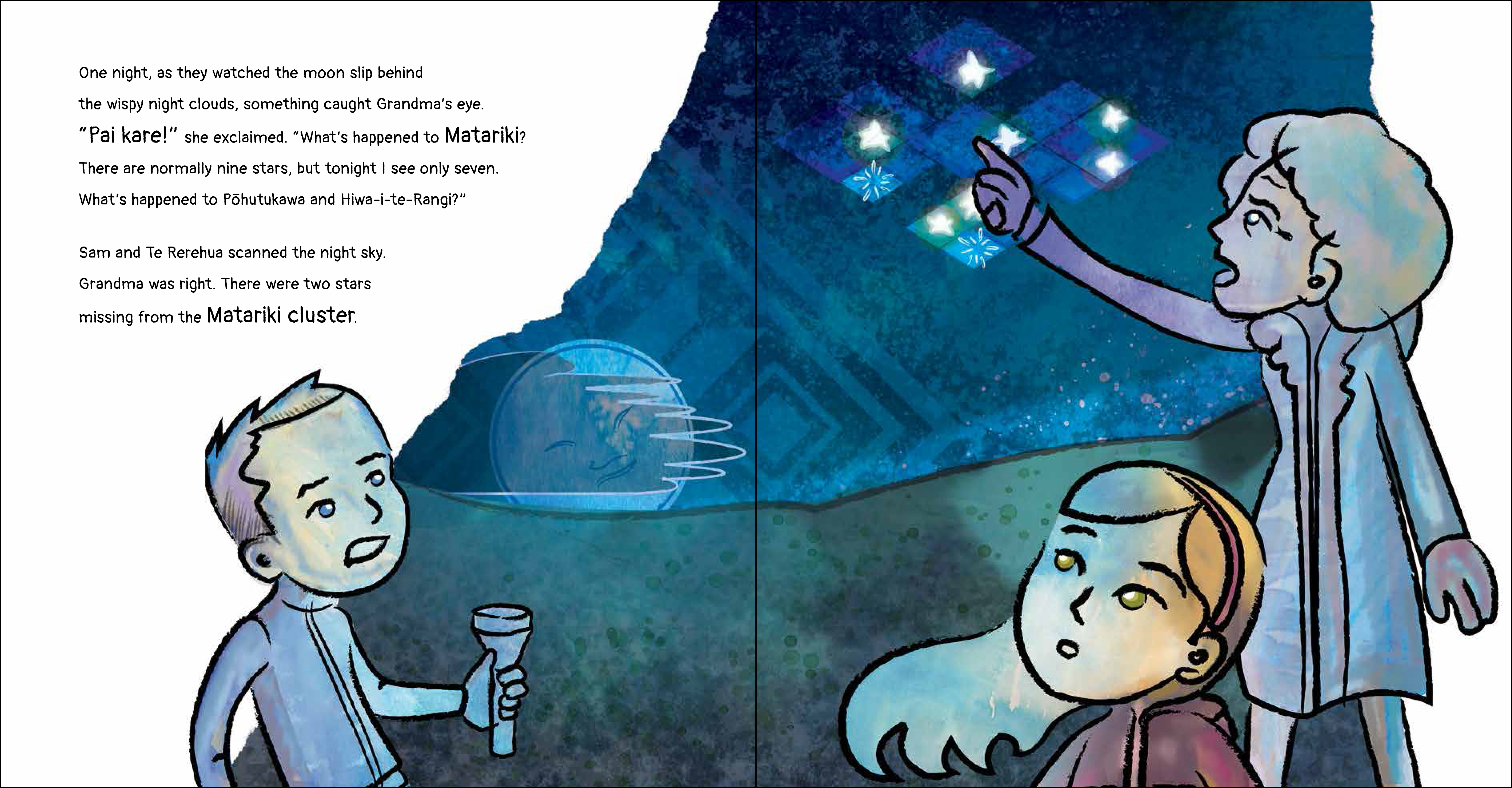

In 2016, Dr Rangi Mātāmua got everyone talking about the nine (not seven!) stars of Matariki. Many of us had grown up with the tale of the seven stars, but Mātāmua pushed back on this kōrero – showing that the idea of seven stars could have come from Pākehā stories about the ‘seven sisters’ of the Pleiades. He re-introduced the other two stars, Pōhutukawa and Hiwa-i-te-Rangi, to the world and we all started frantically trying to work the new names into our best renditions of ‘Tīrama Tīrama Matariki’ (think ‘Twinkle Twinkle’).

A bit more recently, broadcaster and local celeb Miriama Kamo was asked by Scholastic if she’d be interested in writing a new children’s book about the two ‘missing’ stars. The Stolen Stars of Matariki is the result.

Her book plays on our public perceptions of Matariki. In Kamo’s story, it’s some cheeky fairies who steal the stars, but in real life perhaps we can thank Western-centred retellings of Māori stories for that same ‘theft’.

Alongside the rather deep but subtle suggestions in the book about the decolonisation of knowledge, the book is a lovely, warm and funny read for young children. I spoke with Miriama about her experiences writing the book.

Krissie: Well, first of all – let’s make a connection! Nō hea koe? Who are your iwi and where did you grow up?

Miriama: Nō Ōtautahi ahau.

Ko Kāi Tahu me Ngāti Mutunga ōku iwi.

K: We all know you as a teller of stories in the current affairs context, but this is quite a different kind of story. Have you always been a storyteller?

M: I have written stories since I learned to write. My dad used to give me his old diaries and I’d fill the blank pages with stories and pictures. One of my favourite characters was a girl I called Joanie, she got up to all sorts of escapades. I’d write these stories then make my long-suffering and loving family sit down and listen to them.

K: How did this book come about? It’s your first children’s book, right?

M: It’s my first published story, I have written others – hopefully they’ll get an outing now too! Now that I’ve published one, it’s made me feel a bit braver and sharing the other ones.

K: And Sam and Te Rerehua are the names of your own two tamariki in real life, yes? Do they like the story?

M: Yes, those are my kids, and the characters Pōua and Grandma are my parents.

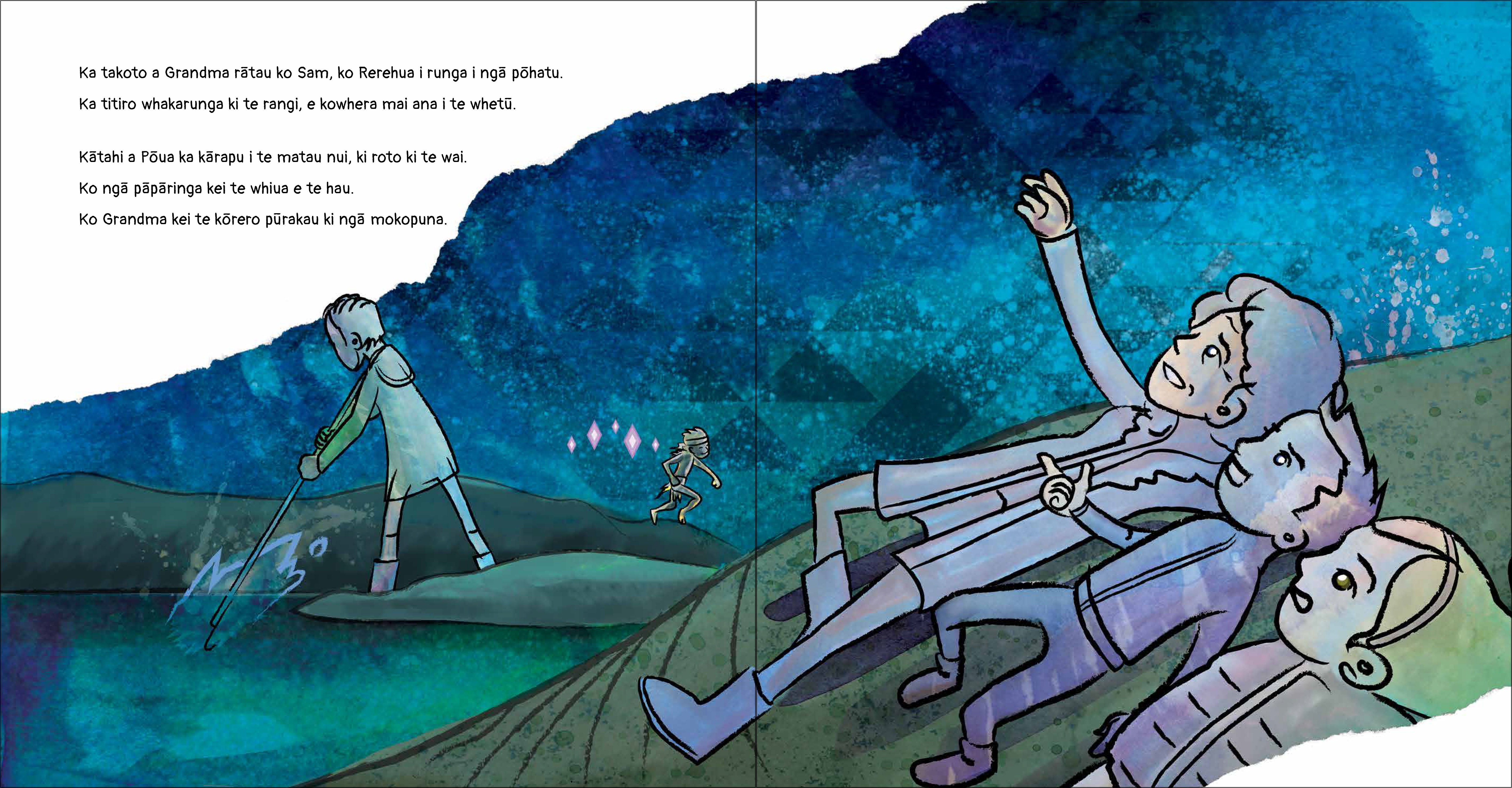

The story reflects mine and my siblings’ upbringing. Mum and Dad took us eeling at Te Mata Hāpuku (Birdlings Flat) all the time when we were kids, because we had a bach there. My Dad’s grand-uncle Jim Whaitiri built the bach and left it to Dad. Our extended family spent a lot of time growing up there too, we and our cousins loved going there and we all feel ownership of the place.

In the book, Grandma lies on the stones with her grandkids, they look up at the stars and she tells them stories – that was how it was for us as kids.

Sam and Te Rerehua are used to me being a storyteller as a job, so they probably were a bit underwhelmed about the book at first – but now that it’s on the shelves, I think they reckon it’s a bit cooler.

K: I’ve been waiting for someone to write a children’s book about the NINE stars of Matariki ever since Rangi Mātāmua’s interview on Te Kārere in 2016. But I was expecting some retellings of old pakiwaitara about the nine stars. Your story is really out of left field! It’s written almost as if it’s a traditional story but in a modern setting and the actual point of the story is not about the star’s origin or anything, but more like a metaphor for how we as a society ‘lost’ them for so long. It’s quite metatextual! What led you down this track?

M: Thank you, that’s lovely feedback.

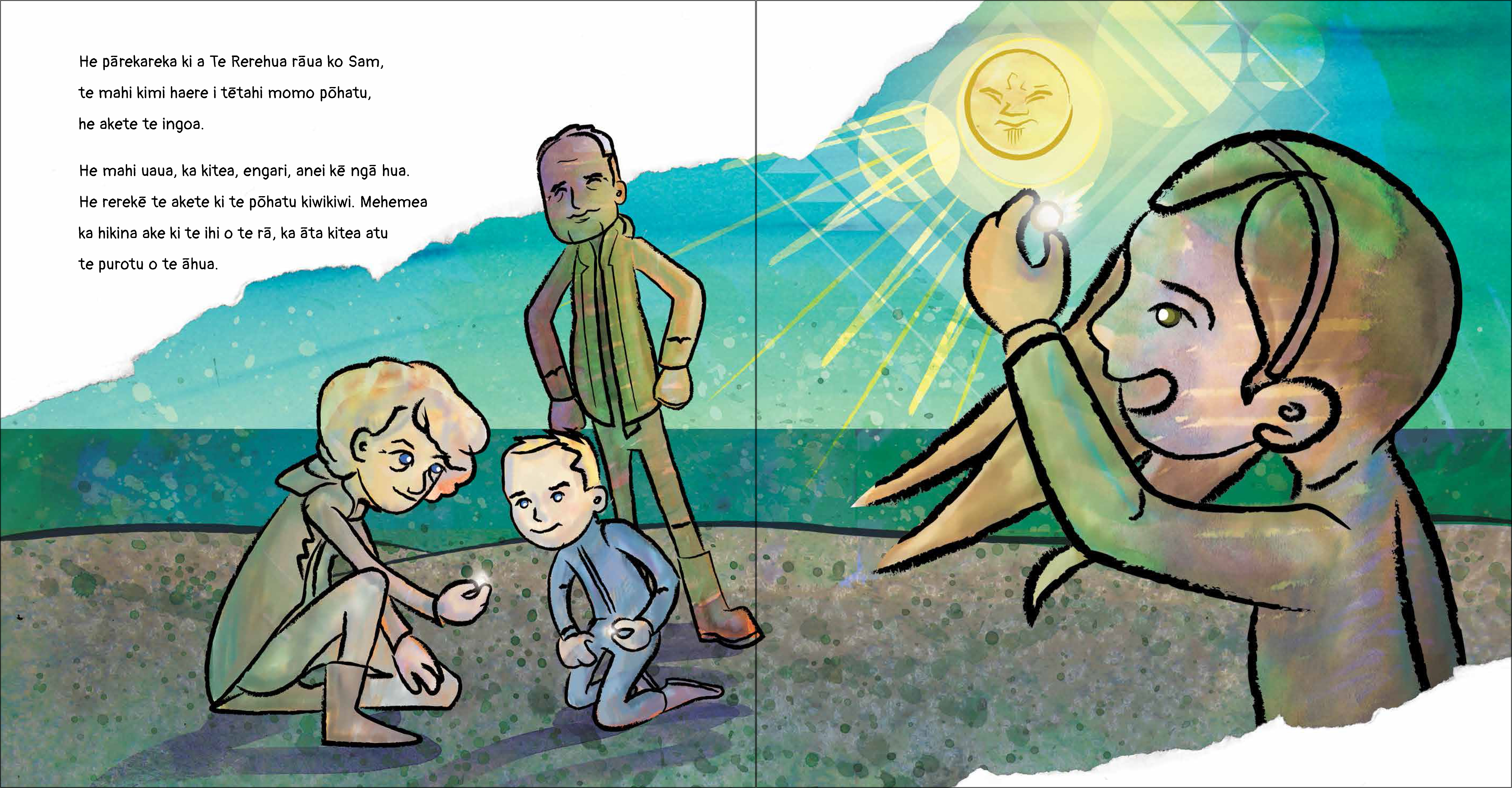

Scholastic, the publishers, suggested I look into the nine-star theory. I wrote the story and then ran it past both Dr Rangi Mātāmua and Rereata Makiha to see what they thought. Their opinion mattered enormously to me, and luckily, they both liked the story.

Te Mata Hāpuku is a very spiritual place, I like to say that it’s wall-to-wall kēhua. You can’t feel ambivalent about the place, it’s wild, windy and magnificent, and people seem to love it or hate it – I adore it. It’s also the place where a lot of ancient battles were fought and an important food basket in Ōtautahi, it’s inspired passion for hundreds of years. There are lots of stories of patupaiarehe and taipō and we were warned of both as kids. And we’ve all had at least one ‘experience’ there, and stories abound of people having all sorts of encounters. My mother used to say that there were, and still are, nights where you open the door to go eeling, and then get the vibe that tonight’s not a good one to go down to the lake – so you close the door and have a night in. So if it is metatextual, perhaps this background explains that to some extent.

Plus, I did want to reflect our love, as a people, for myth – and to create one that, as you say, in a modern setting gives a vehicle for the debate over whether there are nine or seven stars.

K: As I mentioned above, the style of the story feels rooted in pakiwaitara and kōrero pūrākau. Was that always a clear influence for you? Did you grow up hearing a lot of those kōrero from your own iwi?

M: Yes, Māori are storytellers as a people – our world is very informed by that we can see and that we can’t and we enjoy making sense of that through story.

Plus, we care about the metaphysical, whether it’s expressed through religion or, more commonly I think, through myth and legend. I remember as a child thinking how wonderful it was that I had so many gods; the Christian one that we acknowledged at church and the Māori ones which informed our daily lives. It never occurred to me that one set of beliefs could be at odds with the other.

My growing up as Māori has always been engraved with shared stories of the metaphysical, of ghosts, of poltergeists, of dreams, of birds delivering messages, and those wonderful spooky, goosebumpy stories of the inexplicable.

K: The book has been published in both English and Māori, but even the English version has te reo scattered throughout. Do you speak te reo at home?

M: Yes we do, as much as we can. Our daughter is in a bilingual unit at school and attended an immersion daycare. Our challenge is to keep learning so we can support hers.

We’re so proud that she won’t struggle for her reo in the same way that I did. My husband, who’s Pākehā, and I have always felt passionate about her growing up i te ao Māori.

And in my writing, I am always thinking in terms of translation. It’s important to me that I try to contribute to the canon of Māori literature, which I want to make accessible to both Māori and Pākehā, that’s why there’s te reo in the English version too.

I have to mention Ngaere Roberts here, what a beautiful job she did of translating the book. I really feel extraordinarily privileged to have had her contribution on this.

K: Zak Waipara’s pictures are lovely! I love how much they capture the nighttime āhua of the story. Did you know he was going to be the illustrator? Have you ever met him?

M: Yes! Zak’s brother Tama is a good mate of mine. The publishers mentioned they were looking at a few illustrators including Zak. I caught up with Tama and he said, ‘Hey! My brother is illustrating your book.’

I love the strength of his images. I would know his work anywhere – they’re striking and strong.

K: I like to think that telling stories always teaches us something about ourselves – what did you learn about yourself from writing this book?

M: That writing about what you know really is a good strategy. Scholastic suggested I look into the nine-star theory and my husband Mike suggested I set the story at Te Mata Hāpuku – those two suggestions were so important in starting the story off. I wrote about the place I knew and the history of my own whānau.

And it reminded me of how lucky I have been to have grown up in that place with my amazing whānau.

K: Finally – who are your favourite Māori authors of children’s literature? Give us some recommendations!

M: My all-time favourite is Witi Ihimaera – I owe so much of my growth as a reader to him. As a kid, I used to try and write like him too! For young readers, The Little Kowhai Tree, and for readers 8+, I reckon Pounamu Pounamu is a must read.

And we’ve just finished reading the most brilliant book to our six-year-old called Rona, by Chris Szekely – it is the most delightful, authentic, and funny read.

You can read a version of this interview in te reo Māori here.

NGĀ WHETŪ MATARIKI I WHĀNAKOTIA

nā Miriama Kamo rāua ko Zak Waipara

nā Ngaere Roberts ngā kōrero i whakamāori

Scholastic

RRP $17.99

The stolen stars of matariki

By Miriama Kamo

Illustrated by Zak Waipara

Translated by Ngaere Roberts

Scholastic

RRP $17.99

Krissi Smith

Kua roa a Krissi e noho ana i Te Whanganui a Tara nei, i roto rawa i te rohe o Te Āti Awa nō runga i te rangi. Heoi, nō Kōterani kē ōna tīpuna - he tangata mau panekoti, he tangata noho maunga, he tangata whai huruhuru! Kotahi tāna tamāhine haututū - ko Nina Manaia te tou tīrairaka. Nō Rongomaiwahine, nō Ngāti Kahungunu, nō Te Āti Haunui a Pāpārangi hoki tāna hoa wahine. Kua waimarie ia i tana mōhio ki te reo Māori, he taonga nui i kohaina mai i ōna pouako, i ōna tuākana, i ōna hoa anō hoki. I ēnei rā, he kaiako reo Māori ia, he kaituhi, he kaiwhakahaere tānga hoki ki Te Whare Ture Hapori o Te Whanganui a Tara me Te Awa Kairangi. Engari, ko tana tino hiahia i tēnei wā, ko te takoto noa i te moenga mō te rā katoa, pānui pukapuka ai.