When is it okay for creative people to draw on cultural traditions they’re not part of? Illustrator, writer and teacher Zak Waipara has some thoughts about cultural appropriation.

When Neil Gaiman wrote in Stardust, ‘Without our stories we are incomplete,’ he was talking generally about humankind’s need for myths, to make sense of both our world and ourselves.

This is especially true for indigenous people, post-colonisation. So much has been lost, but our stories can be a beacon to find our way home again. This was true for me: I grew up without being immersed in the language of my tūpuna, so the stories of Māui and the Māori Gods were much-needed cultural touchstones. They also fostered a love of world mythology that has never left me.

You see, myths are not just stories, they are actually codes for living in society. In an article about Polynesian folklore, scholars Sharon Black, Thomas Wright, and Lynnette Erickson write, ‘Genuine folklore has been created to teach and to preserve … explanations of the natural, supernatural, and human phenomena’. Pūrākau Māori (Māori myths) are no different.

…myths are not just stories, they are actually codes for living in society.

Sometimes this aspect is overlooked in the hunt for new story ideas, especially as the juggernaut of globalisation (or Colonisation 2.0) rolls on. As Gaiman says, ‘…too often myths are uninspected. We bring them out without looking at what they represent, nor what they mean.’

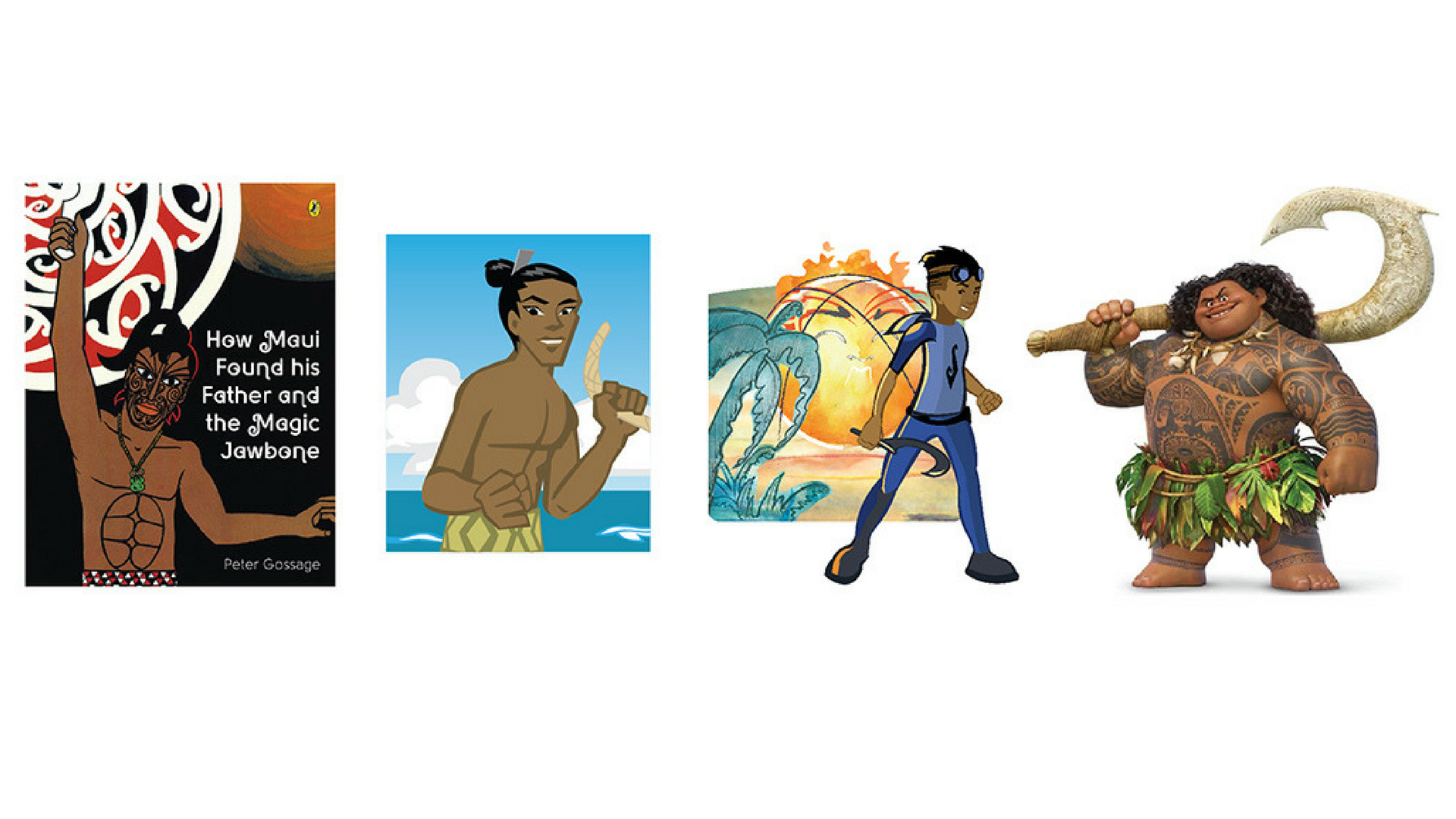

Take Disney/Pixar’s recent film Moana. Judging the film’s merits is not the point of this article, since there are enough voices doing that job already (you can read two here and here.) What concerns me is that as a hybrid story, drawn from various cultures of the Pacific, it really belongs to none of them. To paraphrase Robert McKee, arguing against the homogenisation of stories, a story should be universal in its appeal, but culturally specific. Creators of films like Moana need a sound understanding of the culture they are portraying.

From a Māori perspective, the film misses out on some key cultural aspects of the characters. As Gavin Bishop noted at the recent Storylines Hui, in Māori tradition Māui-pōtiki is the youngest and smallest of his brothers, rather than the hulked up muscle-bound jokester that Disney has portrayed. His near still-birth made him sickly and weak, and only the intervention of Gods and supernatural entities ensured his survival. In Hana Hiraina Erlbeck’s Māui: Legend of the Demigod Māui-tiki-tiki-a-Taranga she even names him Māuiui (sick or ill).

Māui’s position as lastborn (pōtiki) male meant that he began his life with low status. The eldest child in each line (male and female) inherits the mana within that whānau. The tale of Māui establishes this societal norm but also sets a precedent for overthrowing convention – by dint of intellect, talent and supernatural, self-endowed mana.

Māui’s hook is not just a magic fishhook, but a jawbone taken from an ancestor. The jawbone is a metaphor for speech. In an oral culture like our own, this metaphor is important. Sound preceded all things in the universe. Our creation story is a chant, and speech is the primary means of transmitting cultural knowledge. Most myths contain such deep layers of allusion – for instance King Arthur’s sword, drawn from the stone, is a metaphor for metallurgy.

Māui’s hook is not just a magic fishhook, but a jawbone taken from an ancestor. The jawbone is a metaphor for speech. In an oral culture like our own, this metaphor is important.

Interestingly, in the redubbed Māori language version of Moana, the story had to be refitted in places to align with tikanga. For example, it is not the done thing to shout at the ocean, as Moana does in the film, and so the translators softened the dialogue at this point in the story.

At the other end of the spectrum, we might encounter resistance to new retellings from within Māoridom itself. During the same Hui, writer Darryn Joseph talked about the elders who seek to preserve what precious remnants of our stories remain, and rightly so. Sometimes this attitude results in extreme wariness, conservatism, or even hostility. And yet retelling is vital.

At the IBBY Congress 2016, Witi Ihimaera sounded a call to action, when he said, ‘If we stop telling our stories we foreclose on our future.’ Culture is not static; it is part of a continuum, in the same way that whakapapa is. Think of an unending rope, where all the strands woven together provide strength. It recedes into the past, and proceeds into the future. If the rope is cut our connection to the past is lost. Where innovation is adopted, new strands must be woven into those that already exist, in such a way that the rope is strengthened, not weakened.

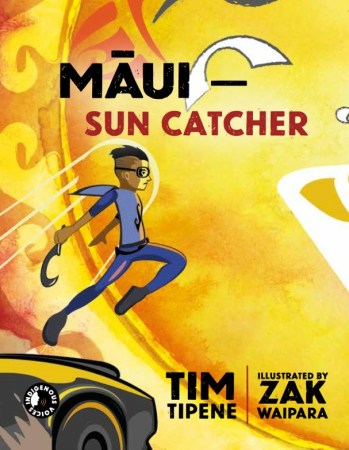

Two of my favourite examples of innovation in Māori storytelling are Patricia Grace’s short story ‘The Sun’s Marbles’ (from The Sky People and other Stories), which deftly combines a scientific understanding of the universe with a dark, wry re-examination of Māui’s earlier exploits; and Robyn Kahukiwa’s Supaheroes: Te Wero, which introduces original, contemporary Māori superheroes, Māui and Hina, who connect via whakapapa to the old Polynesian gods.

So, what about the author with a burning desire to retell a myth from outside their own cultural experience? I am sometimes approached directly with this question, but have no desire to be a gatekeeper, only an interest in applying kaitiakitanga (guardianship) to build bridges toward understanding. Perhaps we might take a lesson from Māori designer Johnson Witehira, who, aware of the growing use of traditional Māori design elements by both Māori and non-Māori designers, generously set about developing some principles to assist in their use. Can we do the same with stories? Where might an author start? Helpfully this proverb provides a useful framework:

Mā te rongo ka mohio (Through perception comes awareness)

Mā te mohio ka marama (Through awareness comes understanding)

Mā te marama ka matau (Through understanding comes knowledge)

Mā te matau ka ora (Through knowledge comes well-being)

Mā te rongo ka mohio (Through perception comes awareness)

The first step in any journey into the unknown is acknowledge your own ignorance, setting aside superficial familiarity. I say this not as an expert, but as a student still finding my own way toward answers. You might try talking to kaumatua as one avenue, but be aware that different tribal versions of stories often exist. Some stories are specific to just one iwi. Where possible, try to go back to the original source material, analytical writing on the topic, or research as many versions as possible. Beware of the bowdlerization of stories, such as the conflation of patupaiarehe with diminutive Victorian pixies (themselves a reduction of much more dangerous and powerful Celtic fairy peoples).

The first step in any journey into the unknown is acknowledge your own ignorance, setting aside superficial familiarity.

Mā te mohio ka marama (Through awareness comes understanding)

The adoption of Māori words is a positive thing for the naturalisation and normalisation of te reo Māori amongst the general population, but diving into mythology will require a stronger and more genuine commitment to the language. In my own journey I tried to rectify my lack of fluency by going to te reo Māori classes and attending noho marae.

Every language is a window into a different way of seeing the world, a way of putting ourselves in others’ shoes – which as authors we should be trying to do. Māori already stand in two worlds: Kei te taha o toku matua, he Māori, he Pākehā au, kei te taha o toku whaea, he Māori, he Pākehā hoki.

Mā te marama ka matau (Through understanding comes knowledge)

As poet Robert Sullivan has shared, because so much of te reo Māori draws on poetry and makes reference to pakiwaitara, Governor George Grey only fully started to understand conversational language when he collected these stories together in the nineteenth century (though this insight was then used directly against Māori). Some concepts don’t translate well and are best understood in the greater context of the language. Subtle shades of meaning can be conveyed through choice of words and their arrangement.

As just one example, passive verbs are a common feature of te reo Māori – emphasizing that a task has been done, rather than on who did it, which expresses the communal nature of work and existence, rather than a Western celebration of individual effort.

Mā te matau ka ora (Through knowledge comes well-being)

Knowledge is not attained overnight, and that might seem daunting to those with deadlines – the enemy of creative people, the feeling that you can’t do a story justice because of time pressure – but at the Hui various authors talked about manuscripts sitting unused for years.

Though learning is life-long, hopefully after embarking on any such undertaking, the author or artist can now answer that question themselves, ‘Is this my story to tell?’ And their own answer might be no. But they’ll be a richer and wiser creative person as a result, whether the story comes to fruition or not. Whaia te iti kahurangi, ki te tuohu koe, me he maunga teitei. Seek that which is most precious, if you should bow, let it be to a lofty mountain.

Editors’ note: The Reckoning is a regular column where children’s literature experts air their thoughts, views and grievances. They’re not necessarily the views of the editors or our readers. We would love to hear your response to any of The Reckonings – join in the discussion over on Facebook.

Zak Waipara

Zak Waipara (Rongowhakaata, Ngāti Ruapani, Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kahungunu), has illustrated and written for children’s books, comics, newspaper graphics, motion graphics and animations. Zak has lectured in Digital Media at AUT and Narrative Studies at Animation College.

You can follow his blog about creative work here and the progress of his current project, a Māori comic called Ōtea,here.