Gillian Candler argues for more recognition of the importance of New Zealand non-fiction books for children, while at the same time wishing there was another term to describe these bound paper receptacles of creativity, serendipity and juicy, rich morsels.

I wish there was another name for ‘non-fiction’. It seems a shame to use a negative to define what can be such imaginative and creative works that describe our marvellous world as it is. ‘Non-fiction’ describes what they are not, rather than what they are. It is such a dreary term that publishers of adult non-fiction have resorted to using phrases such as ‘creative non-fiction’ or ‘literary non-fiction’ to give their publications more weight and make them sound more interesting.

In children’s publishing, the UK School Library Association and the Children’s Book Council of Australia have both replaced ‘non-fiction’ with ‘Information Book’ in their awards. While ‘information book’ might be an improvement on ‘non-fiction’, to my mind it doesn’t capture the ability of non-fiction to tell a story, suggesting rather that such works will be a list of facts which could be easily found on the internet. (Although, and this is a topic for another Reckoning, in reality, online information about New Zealand written in a manner that is suitable for young children is scarce.)

It seems a shame to use a negative to define what can be such imaginative and creative works that describe our marvellous world as it is.

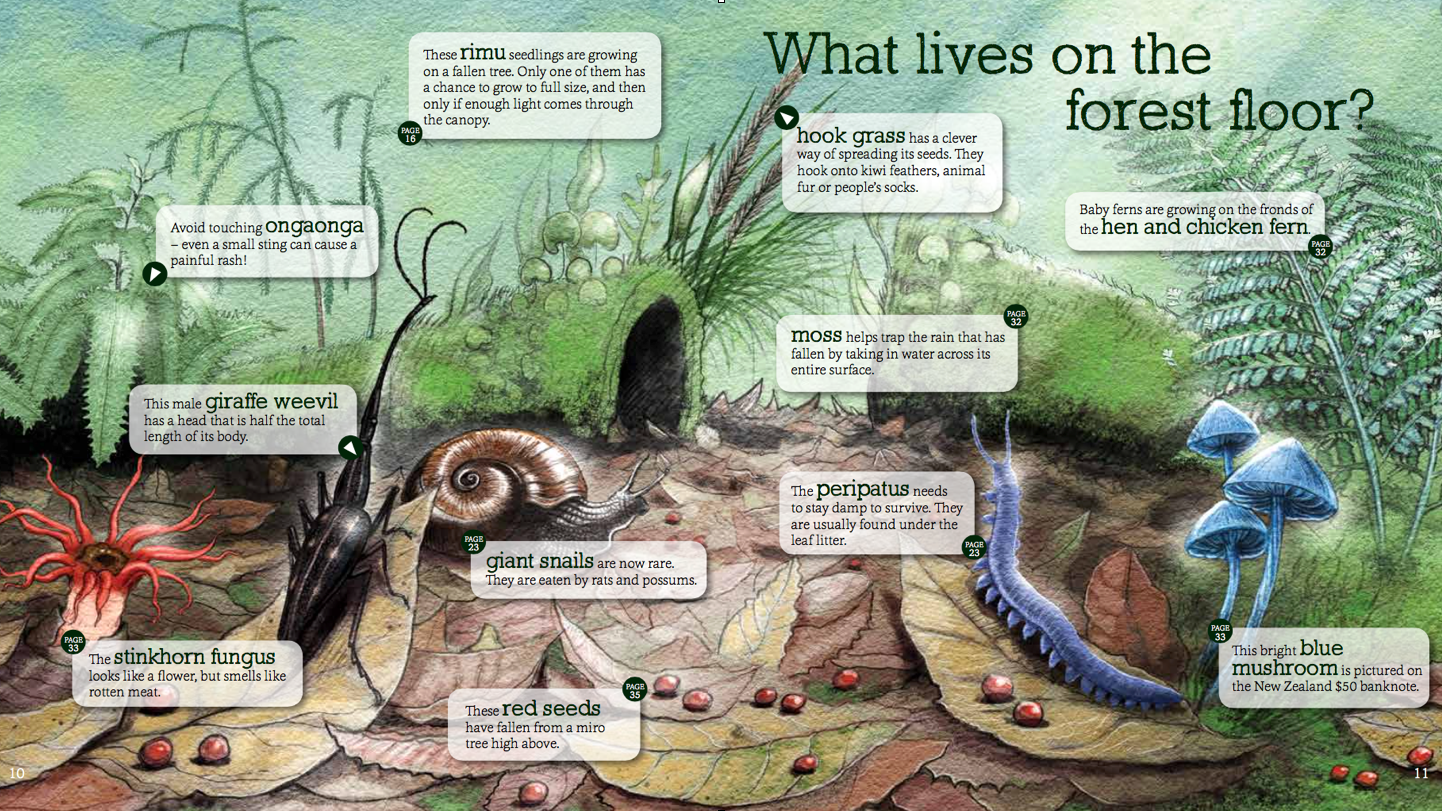

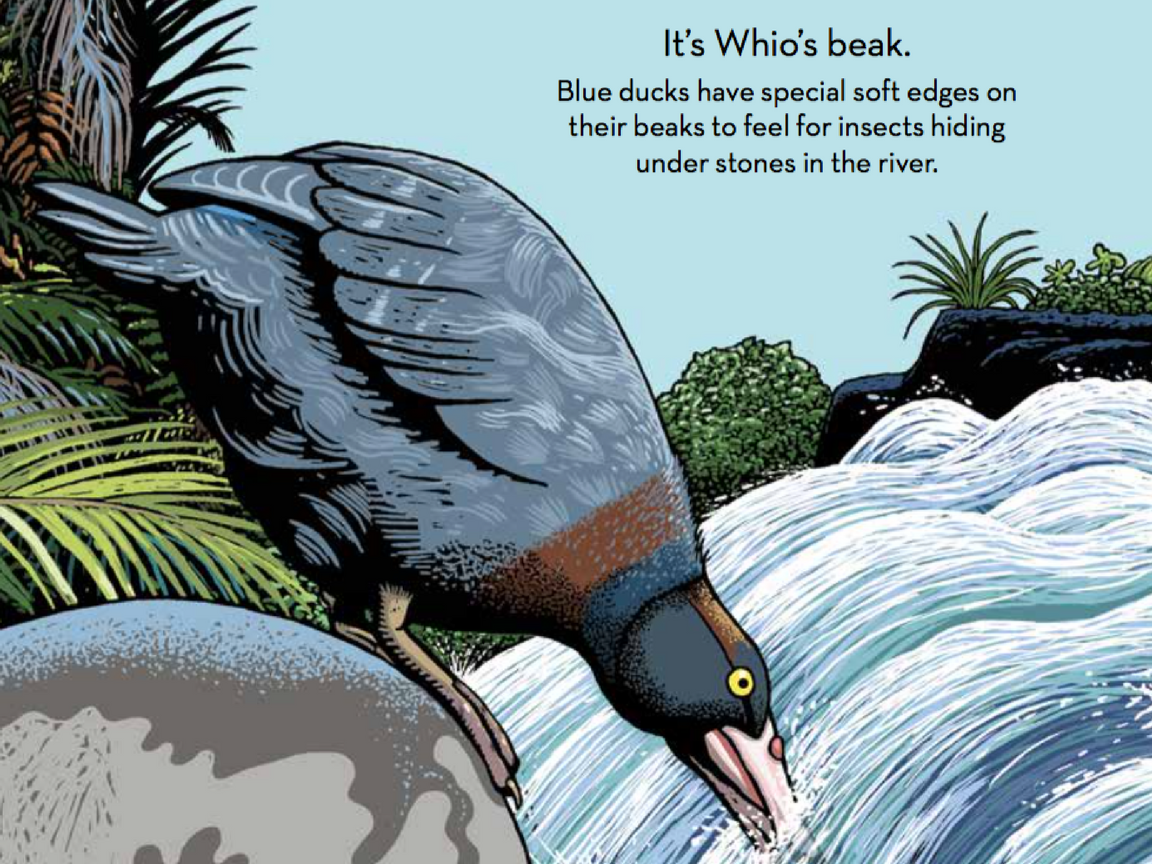

Good non-fiction books are more than a list of facts. They present concepts in accessible and creative ways. At least this is what I hope my books do. In Whose Beak Is This?, illustrated by Fraser Williamson, the concept of animal adaptation is conveyed through a guessing game; while my ‘explore and discover’ series introduces the idea of eco-systems through Ned Barraud’s detailed cross-section illustrations. Non-fiction books use story to add richness to information, as in Nice Day for a War: Adventures of a Kiwi Soldier in World War One by Chris Slane and Matt Elliott, which follows the real-life war experience of one of the author’s grandfathers and employs graphic novel techniques to develop a sense of story to this factual account. In Motiti Blue and the Oil Spill by Debbie McCauley, one penguin’s story is used to exemplify the facts about both the oil spill and little blue penguins.

Factual books open windows and doors as children stumble on ideas through serendipity and linger over them rather than click away. This is neatly summed up in a true story from Nobel Prize-winner Alan MacDiarmid’s childhood. In Charged: MacDiarmid’s Electroplastic by Pat Quinn, MacDiarmid describes how as a boy he found a book on Chemistry in the attic and, as it was too difficult to understand, he ‘headed for the public library. I found … a blue book. It was called The Boy Chemist. Over the following year, I borrowed the book as often as the library would let me … That was a real turning point in my life.’

Factual books open windows and doors as children stumble on ideas through serendipity and linger over them rather than click away.

I like to think of children discovering and emulating Māori artists through Māori Art for Kids by Julia Noanoa and Norm Heke, being inspired to keep a nature journal by Sandra Morris’s A New Zealand Nature Journal, absorbing New Zealand history through Digging up the Past by David Veart and aspiring to become an archaeologist or taking up triathlons after reading The Beginner’s Guide to Adventure Sport by Steve Gurney. These books, along with biographies, histories, science books, how-to books, comprise the ‘literature of fact’.

The literature of fact, has taken on a new importance in a world where fake news has become a global concern. I believe its time to start describing our non-fiction books as ‘factual books’, to start having the conversation with our children about the difference between fact and fiction so that they will learn to distinguish this themselves.

Disappointingly few factual books are written (or published) for children in New Zealand. Back in 2012, when I judged the NZ Children’s Book Awards, only 13 books were entered in the non-fiction category compared to nearly ten times that number across the fiction categories. The low number seems to justify the reason there is only one non-fiction category covering all ages in the awards, but the single award does nothing to encourage more non-fiction publishing. And it seems the cost of publishing non-fiction, with its, often, more costly design and layout, deters many New Zealand publishers.

But internationally things are changing: non-fiction has seen a design-driven resurgence with large, sumptuous, highly illustrated titles hitting the shelves. With a larger audience, international publishers are often prepared to take the risk of a more expensive format that would be uneconomic if just printed for New Zealand audiences; for example, larger size or pop-up books. While the beautiful illustrations and designs will capture imaginations and engage children, their rich and often quirky content rarely includes New Zealand material. One might hope, for example, that Animalium might include a New Zealand animal or two given the exceptional nature of our wildlife, from tuatara through giant weta to kākāpō we have our share of oddities, but sadly it doesn’t.

While such interesting books deserve a place on our shelves, our children need to see New Zealand content pictured too. We aren’t short of the creative talent to create such books. I hope Creative New Zealand is taking notice and is supporting the development and publication of creative children’s non-fiction.

What children need is not either fiction or non-fiction but both, local and international. Both fiction and factual books inform and stir the imagination. As adult readers we learn from both, are entertained by both; for children it’s no different, although they approach non-fiction with greater sense of wonder than do adults. It’s time for adult buyers of children’s books to recognise that factual writing also stirs imagination and encourages creativity, that children need facts as much as they need fiction. It’s time to rename non-fiction writing as the ‘literature of fact’ and non-fiction books as ‘factual books’.

Editors’ note: The Reckoning is a regular column where children’s literature experts air their thoughts, views and grievances. They’re not necessarily the views of the editors or our readers. We would love to hear your response to any of The Reckonings – join in the discussion over on Facebook.

Gillian Candler

Gillian Candler is the author of the ‘explore and discover’ series for children, as well as other titles about New Zealand nature. After spending time publishing specifically for schools, Gillian is enjoying creating non-fiction books for general audiences that are bought (or borrowed) by parents, grandparents and children to enjoy at home or out in the field, as well as in classrooms. She currently works as a writer and a publishing and education consultant from her home in Pukerua Bay.