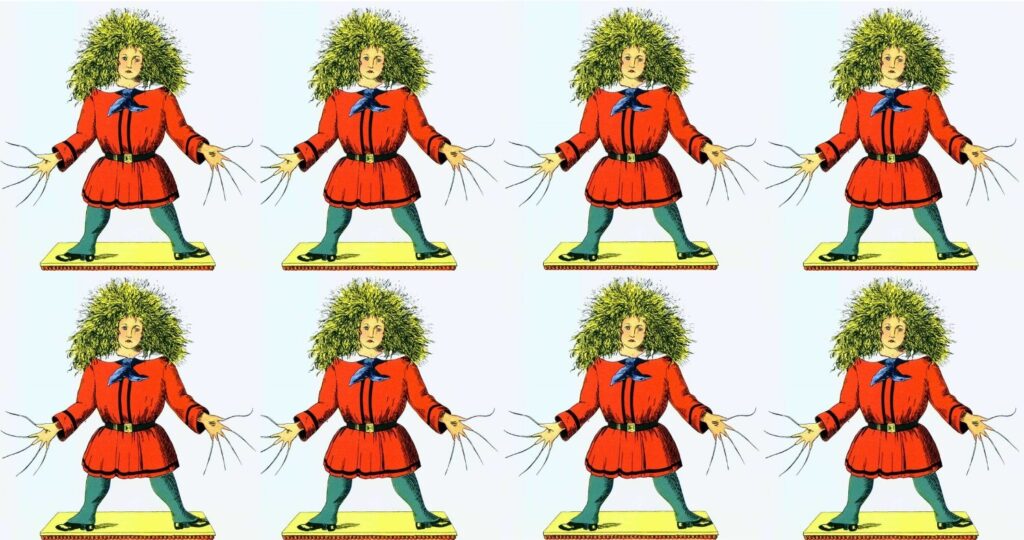

Playwright and Victoria University Writer-in-Residence Victor Rodger describes the twisted humour and terrifying morality of his favourite childhood book, Struwwelpeter.

If you ask me about the children’s book I most treasured during my childhood, there can and will only ever be one answer: Struwwelpeter, aka Shockheaded Peter, by Dr Heinrich Hoffman (1845). Or, as I like to think of it, the Requiem for a Dream of children’s books.

Dismay, Dismemberment, Death: it’s all there in Hoffman’s eleven cautionary tales which were originally subtitled Merry Stories and Funny Pictures in a clear example of high irony. These stories are deliciously and deliberately dark. That’s obviously what made them so appealing to me as a child.

Herr Hoffman, a German psychiatrist, wrote and illustrated Struwwelpeter for his own son when he was dissatisfied with the existing children’s literature of the time. It’s a love-gift that has endured for over two centuries, a tribute in no short part to Hoffman’s wonderfully droll sense of humour.

My mother bought Struwwelpeter for me because she’d been entranced as a child when one of her school teachers read ‘The Story of Augustus, Who Would Not Have Any Soup’ aloud to her class. In a nutshell: chubby Augustus boycotts the soup that is presented to him each night and essentially goes on a hunger strike. Eventually he starves himself to death rather than eat the accursed soup. (Talk about stubborn.)

One thing I truly loved and still love about Struwwelpeter: there’s no room for sentiment. These stories are about choices and consequences; more so, how bad choices have sometimes dire consequences. All the children in Struwwelpeter make the wrong choices and end up paying the price, sometimes with their lives, like poor old Augustus.

Not all of the stories are nearly so dramatic: there is the little boy who walks around with his nose up in the air and falls into a river; the fidgety rascal who comes a cropper when he keeps swinging back and forth on his chair at the dinner table; the junior sadist who whips a dog only for the dog to turn around and sink his teeth into him until he draws blood.

But then there are the stories that really get down to business, stories that have no doubt been used by parents over the last two centuries to keep recalcitrant offspring in line.

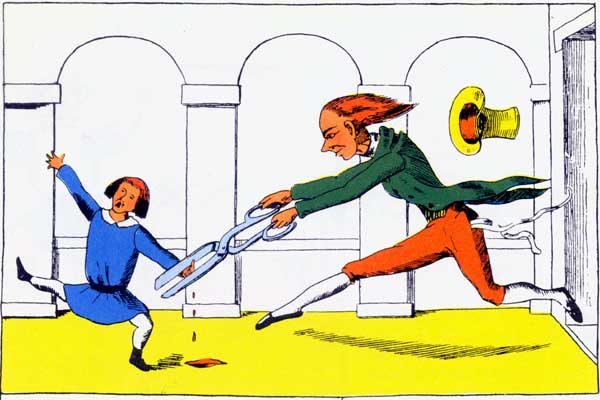

You have a kid who’s a thumbsucker? Sit ’em down and read ‘em ‘The Story of Little Suck-a-Thumb’: Mother warns Son that if he sucks his thumbs, a great tall tailor will cut his thumbs off with some scissors; Son ignores Mother and gets a-suckin’; sure enough, Little Suck-a-Thumb becomes Little Suck-a-Thumbless after the great tall tailor bursts through the front door with some gigantic scissors.

Got a budding pyromaniac on your hands? Settle down and lay ‘The Dreadful Story of Harriet and the Matches’ on them: where the titular firestarter ignores all warnings against playing with matches (from her mother, her nurse and even her pussycats), then inadvertently sets herself alight and burns to death.

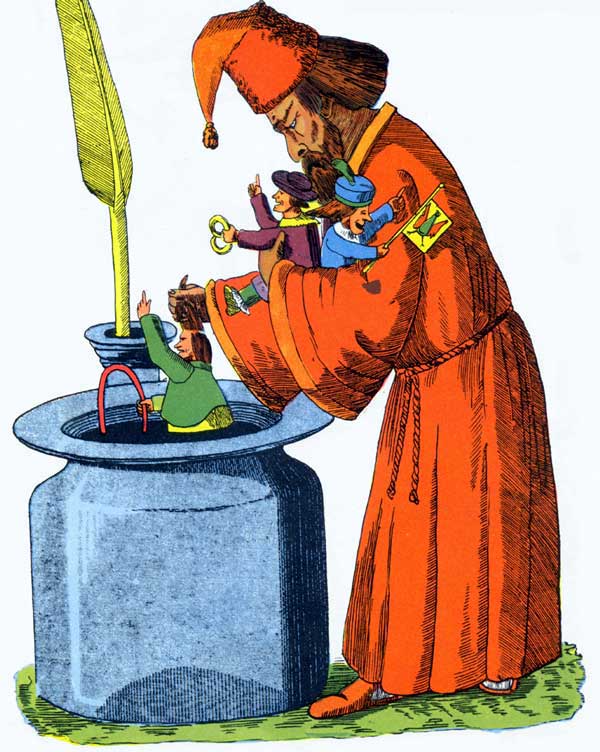

My favourite story of the bunch has always been ‘The Story of the Inky Boys’, a story which deals with racism.

Arthur, Ned and William (who obviously would have grown up and voted for Trump if they’d been born in modern times) are three racist little toads who taunt a black kid as he walks along, minding his own business. Agrippa, some sort of giant, obviously possesses a progressive social conscience and isn’t having a bar of it: he hears the boys’ taunting and warns the racist trio:

Boys, leave the Black-a-moor alone!

For, if he tries with all his might,

He cannot change from black to white.

The boys are, like, ‘Whatevs, Agrippa,’ and keep hassling the Black-a-Moor.

So what does the socially progressive Agrippa do? He grabs those little rat bags and dips them in a gigantic inkwell. The trio emerge even blacker than the innocent Black-a-Moor. Justice is served.

If that story were written today, I like to think that not only would the unnamed Black-a-Moor have an actual name (something that is only afforded the Inky Boys), but that he would deal to the boys himself without having to rely on a variant of the White Saviour trope to save the day. Having said that, I can’t deny that as a young mixed-race kid growing up in 1970s Christchurch, I got a real kick out of seeing those racist little shits getting their just deserts.

I can easily imagine that in this age of trigger-warnings and Generation Snowflake, some parents and caregivers would today be horrified by some of the content in Struwwelpeter; but they, and the children in their care, would be missing out. For those, like me, who share Hoffman’s unapologetically dark sense of humour, its rewards remain many.

Victor Rodger

Victor Rodger is an award-winning playwright of Samoan and Scottish heritage. His first play, Sons, debuted in 1995. Since then he has had eight other plays produced, both nationally and internationally. He has held writing residencies at the University of Canterbury, the University of Hawai'i and the University of Otago. He is currently the Writer-in-Residence at Victoria University.

A collection of three of his plays, Black Faggot and other plays, has just been published by Victoria University Press.