Briar Lawry finds lots to unpack with two new reads to hit the shelves: a classic gritty YA story that tells a tough tale, and an illustrated novel with an unconventional form.

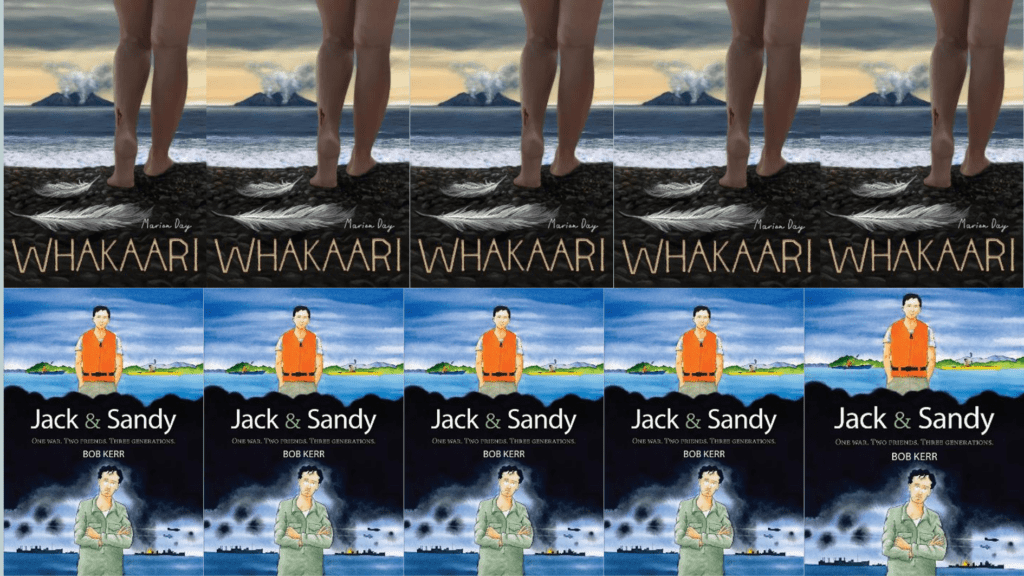

Whakaari, by Marion Day

Young adult books are invariably rife with issues. And when I say issues, I don’t mean plot holes and character inconsistencies and the like. I mean the kind that lurk in the characters’ lives, Issues with a capital ‘I’; life challenges thrown at teens, sometimes one after another. Or sometimes one after another after another after another.

Of course, there’s a point in some books that the Issues become an issue. Where you think—as an adult reader, at least—cool your jets, mate. I told a colleague that I was reviewing this book, Whakaari, shortly after finishing it. Invariably, she asked, ‘What’s it about?’

‘Um. Well. It’s about Roa. A girl with a rough upbringing but an English teacher in her corner at school, but then she gets roped into helping out with a burglary that turns violent and she knocks out an old man and later finds out he died and is eaten up with guilt, and meanwhile she starts seeing a rich Pākehā boy from the school rugby team and then it turns out she got pregnant the first time they slept together and then oh-no, it’s twins but they adapt but then she loses one of the babies…and then she finally comes clean to the cops about her role in the burglary-turned-robbery-turned-manslaughter and ends up in a mother-and-baby unit in prison.’

[Roa has] a rough upbringing but an English teacher in her corner at school, but then she gets roped into helping out with a burglary that turns violent…

But rest assured that very little of that is actually spoilers, because the majority of the key facts are established in the introductory present-day chapter, before diving back to the beginning of where things started to unfurl.

Day does a good job of capturing Roa’s voice, for the most part. I enjoy the idea of her finding an escape through writing, although the design choice of the font for the extracts from her notebooks is appallingly irritating to read after a few lines. She is believable as a character, and there is certainly a good chance that some young readers will see echoes of their own lives in her challenges. The book is set across the water from Whakaari/White Island—hence the title— and Roa frequently relates her own mental state of mind and emotional well-being to the current state of the volcano on the horizon. It’s a metaphor that is easy for any reader to understand, and given everything that is going on in her life, it’s pretty darn apt.

[Roa] is believable as a character, and there is certainly a good chance that some young readers will see echoes of their own lives in her challenges

Day makes an odd choice in including frequent chapters from the perspective of Roa’s mother, Huia. It feels jarring to have this very adult POV in a YA book; it feels like a misunderstanding of YA conventions, rather than something done with intent and purpose. The chapters themselves are actually reasonably interesting, with a couple of caveats: interesting to adult me, not necessarily to fourteen-year-old me when I was reading YA as a youngster myself; and Huia’s perspective confuses the flow of the story and builds it in directions that don’t support the already overwrought plot. Huia’s perspective could work as part of a parallel companion book, actually targeted at adults, perhaps, but the inclusion of her POV doesn’t really work within this.

Poor Huia is also saddled (more so than anyone else) with one of the more unfortunate stylistic choices of the book—clunky attempts at conveying accent or spoken language peculiarities in an onomatopoeic manner. Think, “I’m sorry for what I’ve put ya through. ‘Avin ta watch him hurt me.” It takes away from the emotional weight of lines like those and makes it feel like she’s pretending to be Hagrid. It happens with other characters too, but Huia’s dialogue is the most egregious.

Day makes an odd choice in including frequent chapters from the perspective of Roa’s mother, Huia. It feels jarring to have this very adult POV in a YA book; it feels like a misunderstanding of YA conventions, rather than something done with intent and purpose

Ultimately…it’s a lot. I’m not saying that the level of strife that Whakaari explores is unheard of in people’s lives, but there’s a difference between real-life grim stories and the sorts that you develop on the page for an adolescent audience. Despite an optimistic-ish ending (that, as established, you ultimately know to be the case from the outset), a lot of it feels like a misery porn trudge. Knowing what was to come possibly lessened the emotional blows of the major events—for the better, I would say, given that this is marketed as a YA book, but it also made for less gripping reading.

On the one hand, I want to celebrate that stories reflecting the more challenging corners of Aotearoa’s existence are being told. On the other hand, there are limits to what is sensible to do in a book ostensibly for teenagers. And on another hand (don’t try to keep track of the number of hands), there is the issue of whose story this is to tell. There’s a tension present when such a tragic story of a minority individual is being told by somebody who is not part of that minority. I won’t unpack that further, as it isn’t for me to do so, but it’s worth flagging.

There’s a tension present when such a tragic story of a minority individual is being told by somebody who is not part of that minority

Does this book hit its mark? No. Does it have some really solid bits? Absolutely. Will it find an audience? Hard to say. To me, it might be something appealing to senior high school students who struggle with reading. It’s not for adults, it’s not really for the main target age bracket for YA, but for people who slip into the middle, who have challenging lives and want to see a bit of themselves on the page, it could be well worthwhile.

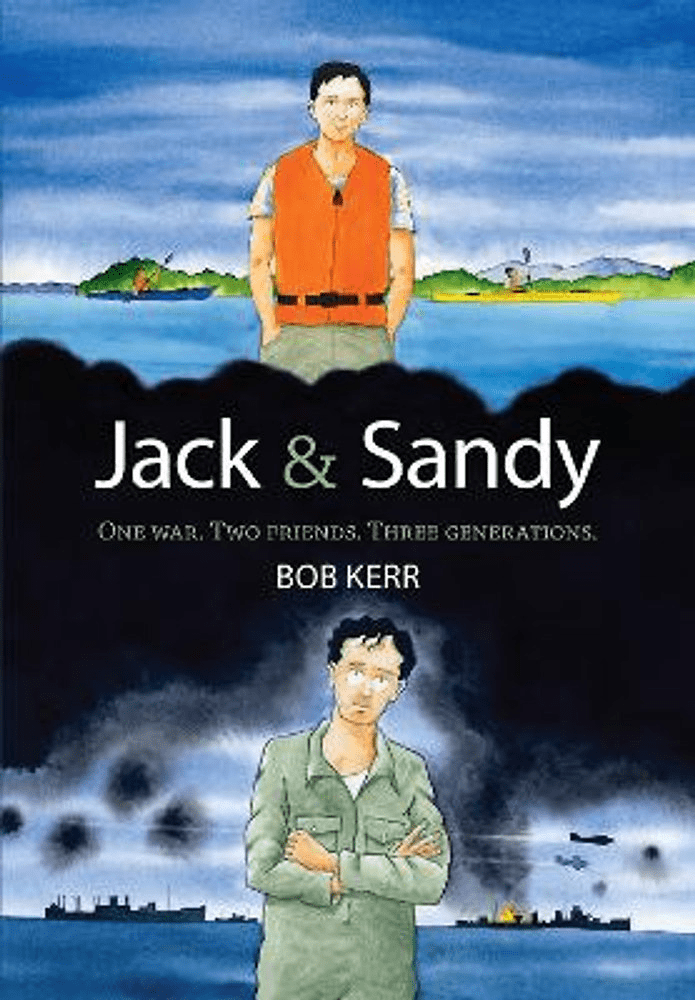

Jack & Sandy, by Bob Kerr

This, I must say, is a great little book. Little being the operative word—it’s a slim thing, with a great deal of page space allocated to graphics. The majority are simply illustrations, but there are also photo and full-page comic panels designed to enhance the story. For a confident reader, it’s a quick read—for a less confident reader, it may not be quick, but it is engaging and not too overwhelming in terms of words on the page. Win-win.

The time period jumps could have been confusing, but they are well indicated and each section feels almost like a standalone tale within the greater context of the story. I enjoyed getting to know the characters, and the attention to detail paid in developing their voices and personalities in a limited number of pages is really quite something.

I enjoyed getting to know the characters, and the attention to detail paid in developing their voices and personalities in a limited number of pages is really quite something

The historical parts of the story are a wonderful combination of significant wartime events with details of day-to-day life that elevate the story from feeling like a social studies reading assignment. We get to know the title characters—Jack and Sandy—but also other family members like Alec and Mary, allowing the threads to connect and become clear. The writing is clear and evocative in a way that allows it a nice and broad appeal; I could see anyone from a voracious eight-year-old to an adult reader enjoying the book and taking something from it. Younger readers should probably be advised not to follow in Jack’s kayaking footsteps without an adult present, however!

There’s a real grassroots, relatable feel to all of the characters and their storylines. The rhymes recited while skipping. The fish and chips on a rainy day in Te Aroha. The biscuits and tea in a rest home. The unglamorous, sweaty roles on a ship in wartime. Kerr doesn’t shy away from realism—but he doesn’t take things into gritty or unbearable territory. It doesn’t feel like a story that has been exaggerated or pared back to be more palatable. It just feels true.

The historical parts of the story are a wonderful combination of significant wartime events with details of day-to-day life that elevate the story from feeling like a social studies reading assignment

The illustration side of things is interesting. I’m not personally a fan of Bob Kerr’s illustration style here—it makes the book feel younger than it needs to. I’ll admit that this may be a me problem, rather than a problem with the book—I’m put in the mind of Nick Sharratt’s cover illustrations of Jacqueline Wilson books making me avoid them for years because they looked way too babyish for me, a very grown-up reader, thank you very much. Kerr’s illustrations have absolutely no visual similarity to Sharratt’s, to be clear—but there’s a quality to them that does impact the age assumptions one would make about the book.

I’m also not necessarily that keen on the stylistic decision to throw in comic panels every now and then. There doesn’t seem to be a great deal of rhyme and reason behind when one pops up, and they break the flow of the text in a way that I find disruptive. I fully admit that to others, it may provide a necessary pause for breath, so to speak. But that wasn’t my personal experience. I think that occasional comic panels can be a great tool in non-fiction texts, but they prove a little confusing in the midst of a work of fiction. All that being said, whether conventional or not, the illustrative angle does help strengthen the book’s appeal and accessibility to less confident readers.

The book bills itself as a graphic novel…[but] an ardent graphic novel-reader may find themselves disappointed to find the majority of the story told in regular old blocks of text

The book bills itself as a graphic novel, and I suppose that is true—but I feel like there’s a connotation in the term graphic novel that suggests it is comic-style all the way through, and an ardent graphic novel-reader may find themselves disappointed to find the majority of the story told in regular old blocks of text. If I were pitching this to a reader in my capacity as a bookseller or librarian or teacher, I would call this an illustrated novel, to err on the side of caution.

I suspect that the main target audience of this book is tween and young teen boys, with male leads and the wartime focus. However, as a teacher at a girls’ school, I’m certainly going to be making sure that my school’s library has a copy; there’s really quite a broad appeal here to explore a bit of Aotearoa history in a new way.

Briar Lawry is an English teacher and writer from Tāmaki Makaurau. She worked in bookshops for years, most notably Little Unity, and judged the NZCYA Awards in 2020. She was also one of the editors of The Sapling between 2019 and 2023.