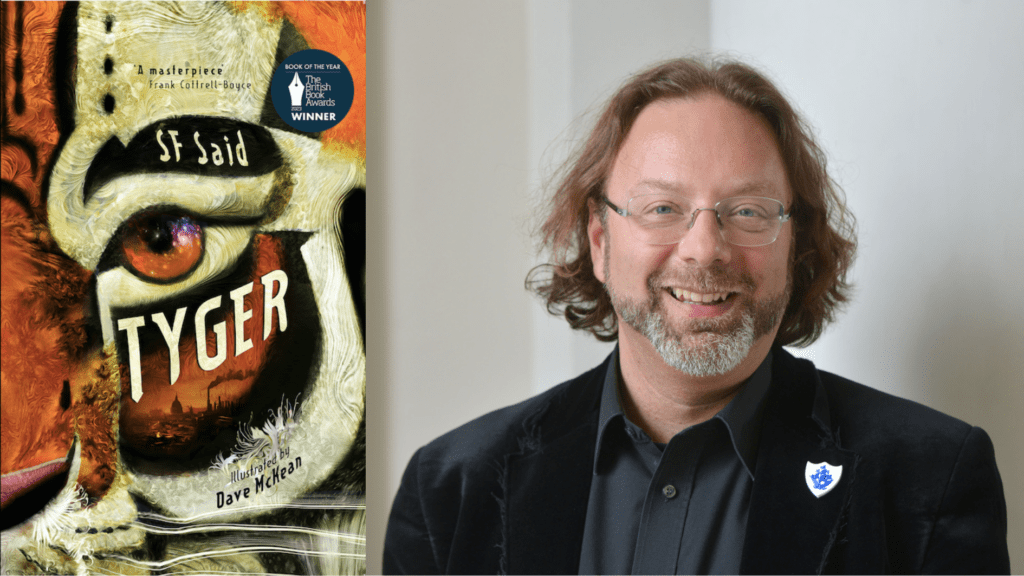

SF Said’s visionary tale Tyger finally makes its way to Aotearoa bookshops this month. Already published to lavish acclaim in the United Kingdom, the book takes the mythic work of the great William Blake as inspiration for a middle grade novel – but really a novel for everybody – set in an alternative London. Here, the British Empire still reigns, and slavery has not been abolished. Navigating the dangerous streets of the city, simply to make deliveries for his family’s shop, Alhambra & Company, young Adam stumbles on a mythical, magical beast – the tyger.

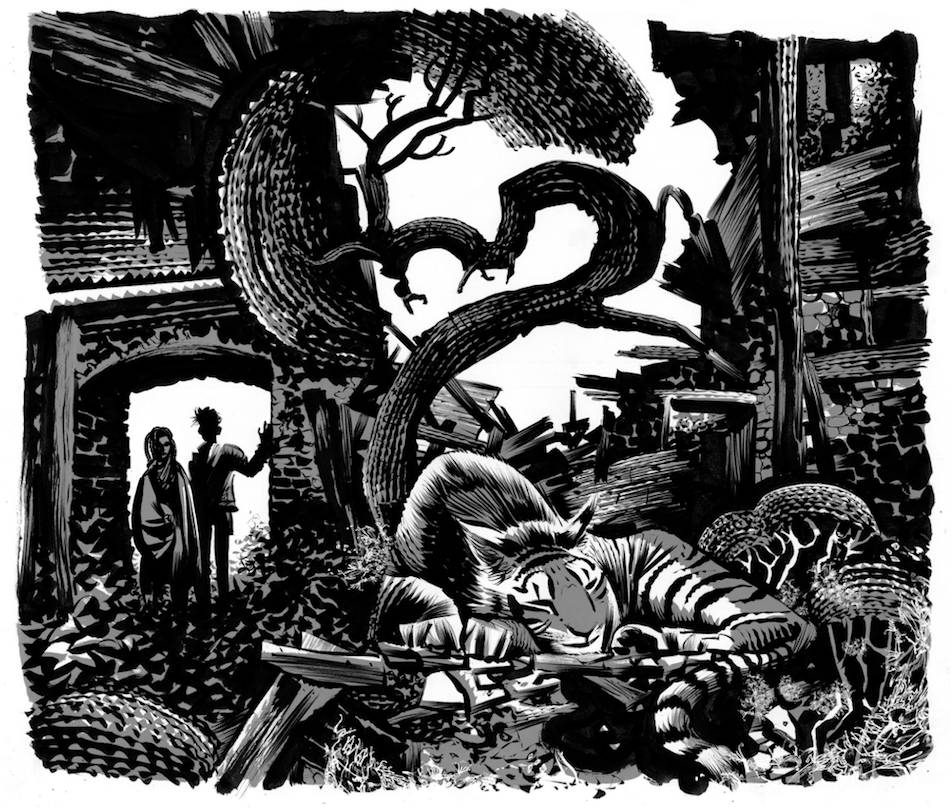

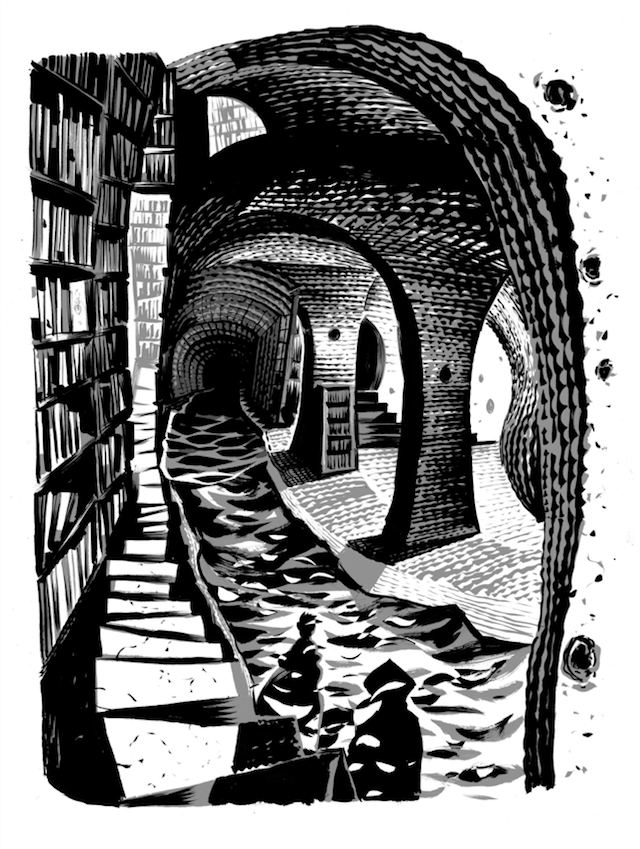

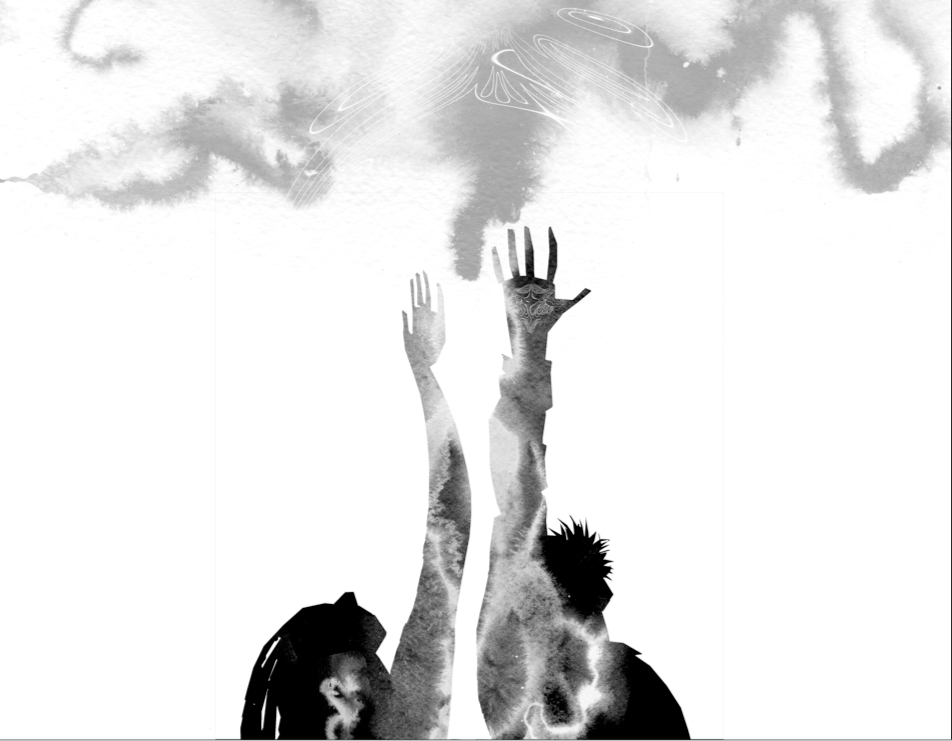

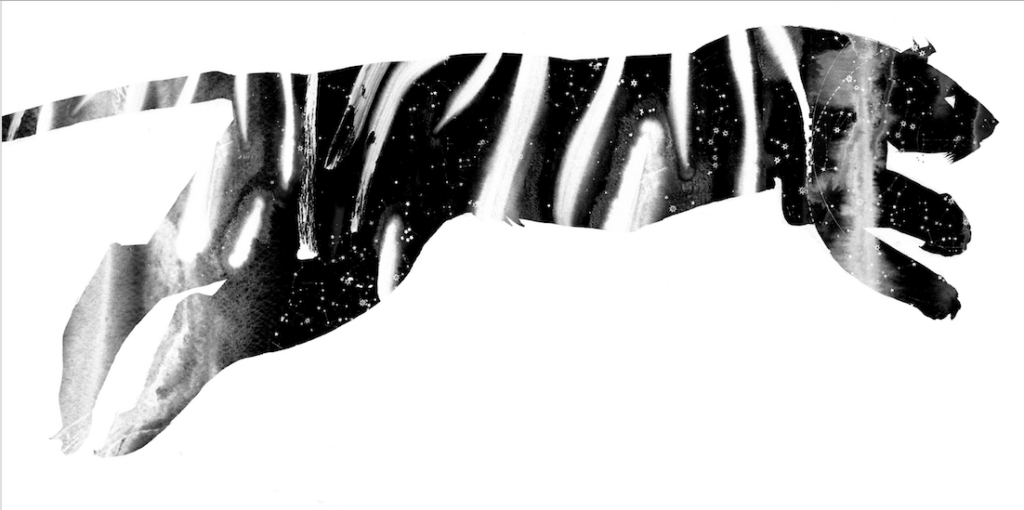

Among its many complex ideas, the novel explores the power of art to make great change in an unjust society. With stunning cover and interior illustrations by Dave McKean, this is a book to treasure and to read more than once. Rachael King had many questions when she finished reading it, and was delighted when SF Said agreed to answer them.

Rachael King: First up, can you describe your relationship history with William Blake and his work?

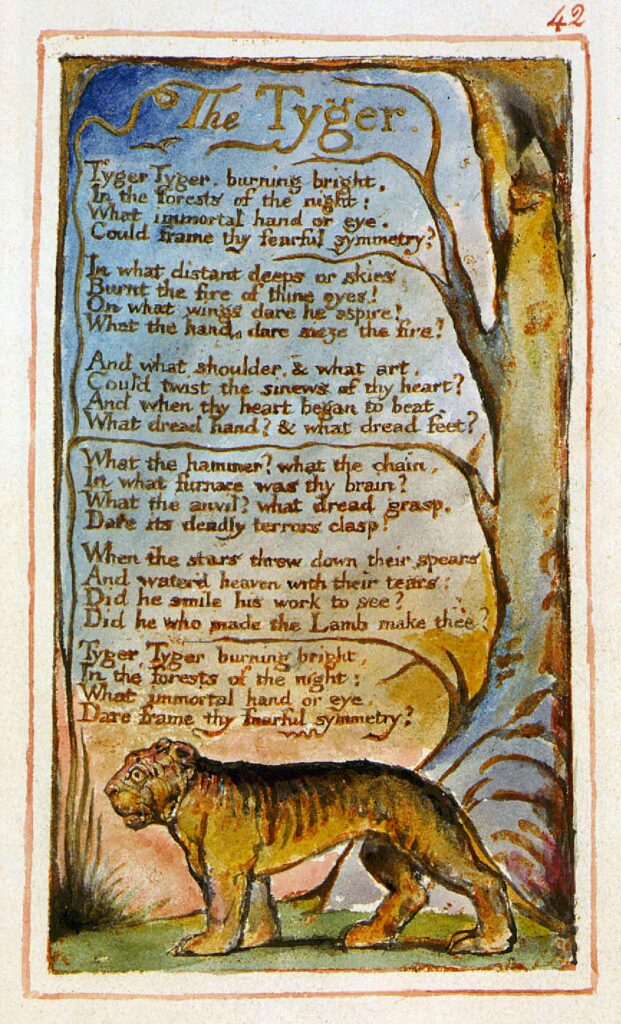

SF Said: I remember reading Blake’s poem The Tyger when I was a child, at school. “Tyger Tyger burning bright” – I was mesmerised by those lines. The poem felt so magical and mysterious. It had the power of a myth for me – and I love mythology as much as I love tigers!

That childhood reading was the spark that eventually led to me writing my own Tyger. While I was writing my last book, Phoenix, I started to dream about a book called Tyger. It was always called Tyger, with a y, and there was always a being called a tyger at the heart of it. I could see this tyger; I could even hear the tyger’s voice. But what exactly was it?

To try to understand my idea, I went back to Blake’s poem. I found all the magic and mystery still there, stronger than ever. And then I went on to read all of Blake’s other work, and to look at his art, and read about his life. And all of that inspired the writing of Tyger.

RK: How did you approach the weaving of his ideas into Tyger?

SFS: Tyger is set in London, in the present day, but in a strange alternate world where history has gone very differently. In this world, the British Empire has never ended, slavery has never been abolished, and huge numbers of animals have been hunted to extinction. And yet it’s in this world that a boy called Adam and a girl called Zadie meet the mysterious, mythical, magical animal known as Tyger.

The alternate world of Tyger evolved directly out of my research into Blake and his times (1757-1827). Many of the things described in the book are things that really did happen in places like London, not all that long ago. Blake engaged with them all, and I think they remain vital for us to engage with today.

You don’t need to know anything about Blake to enjoy my Tyger, though if you do, you’ll find many resonances and references. Above all, Blake was someone who really did create his own mythology. And the more of his work I read, the more I felt I might be able to do something like that, too. If I had to pick a label for the books I write, I’d pick ‘mythic fiction’.

RK: This book took a relatively long time to write. Did you do much research in that time? What were the other things beside Blake’s work you read or watched that fed into the book and helped it to grow?

SFS: It took me nine years to write Tyger! And yes, all sorts of other things fed into it as well. Among its biggest inspirations were books like Malorie Blackman’s Noughts & Crosses and Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials: those amazing stories that imagine alternate worlds with different histories. I couldn’t have written Tyger without their example.

Other works of mythic fiction were inspirational and important to me, among them the Earthsea books by Ursula Le Guin, Watership Down by Richard Adams, and everything by Alan Garner! Alf Layla wa Layla (the collection of tales from the Muslim world known in English as The Arabian Nights) is deep in Tyger’s DNA, as are magical tales like Skellig by David Almond and The Door In The Air And Other Stories by Margaret Mahy.

It took me nine years to write Tyger!

Lots of non-fiction fed into Tyger too; contemporary books like David Olusoga’s Black And British, and older books by writers such as Olaudah Equiano and Ignatius Sancho. And while Tyger was developing, I was doing photography for a book called London’s Lost Rivers: A Walker’s Guide by Tom Bolton. I loved learning about the forgotten tributaries of the Thames that still run beneath our feet, concreted over, yet still flowing, unstoppable. They ended up playing a big part in the story.

RK: What is your recipe for cooking up a novel? Do you marinate for a long time, slow cook, or flash fry?

SFS: All of that and more! I write my first drafts quickly, without planning – I like the energy of discovering the story along the way. Then I get as much distance from it as I can before reading it through, and that’s when I begin to plan things out and think about how to make it better. So my first drafts are terrible, but that’s OK – it’s much easier to take something terrible and improve it than it is to try and write something brilliant in just one go.

I write my first drafts quickly, without planning – I like the energy of discovering the story along the way.

I do as many drafts as it takes until my books are the very best that I can make them, and that’s why it takes me so many years to write them. My process needs a lot of perseverance, but it’s always worth it in the end. I believe children’s books are the most important books of all, so as a writer, you have to give them everything you’ve got – however hard it might be, and however long it takes.

RK: I feel like you really just touched the surface of this world – would you return to it do you think? I’m thinking about how Philip Pullman didn’t leave His Dark Materials open for a sequel and for Will and Lyra to see each other again, but has expanded the world in other ways.

SFS: It’s certainly possible! I love the idea that there could be an infinite number of alternate worlds, each with a different history – something that quantum physics tells us could very well be true. So there could potentially be an infinite number of stories to be told…

RK: You set the world in an alternative universe where the British Empire is still reigning and slavery has not been abolished. How have children responded to this and has it helped them see inequalities that still exist in British society?

SFS: When I was a child, my favourite books were the ones that took me seriously as a reader; the ones that were honest, and didn’t try to soften or simplify the truth, even when they dealt with difficult subject matter. So that’s the kind of book I always want to write myself.

When I was a child, my favourite books were the ones that took me seriously as a reader; the ones that were honest, and didn’t try to soften or simplify the truth, even when they dealt with difficult subject matter.

Of course, Tyger is a work of fiction set in an alternate world. But if it can help children to think about our world, to have honest conversations about it with parents, teachers, librarians and friends – and if it can help them to imagine a better world, and how we might build it – then I couldn’t ask for more as an author.

RK: You have said that growing up British Muslim in the 1970s: “there were no books that I can remember that in any way reflected my identity or my experiences”. How is that being addressed (or not addressed) in the 2020s do you think?

SFS: That’s true. My family is originally from the Middle East and the wider Muslim world, so my name is Arabic. One reason why I loved Watership Down as a child was that the hero of the rabbit mythology was called El-Ahrairah, which looks a lot like Arabic. That’s the closest I ever came as a child to seeing myself reflected in a book.

When I started writing my first book, Varjak Paw, in 1997, I couldn’t imagine a publisher wanting a story about a Muslim boy of Middle Eastern origin.

When I started writing my first book, Varjak Paw, in 1997, I couldn’t imagine a publisher wanting a story about a Muslim boy of Middle Eastern origin. So I wrote a story about a cat with Mesopotamian ancestors – Mesopotamia being the ancient name of the country we now call Iraq, where some of my own ancestors came from. That was as close as I could get to telling my own story.

But in the years that I was writing Tyger, organisations like the CLPE and BookTrust did a lot of research into representation in children’s books, and there were many conversations that opened things up. And children’s publishing in the UK has now changed to the point where I felt I could publish a book about Muslim characters like Adam and Zadie in Tyger, and that it could appeal to a wide audience. Things have definitely moved in the right direction, and I really hope they continue to progress.

RK: Adam gets the question “where are you really from?” By putting it in the book are you hoping to recognise children’s experience as well as educate people about why it is problematic or inappropriate?

SFS: Many of the things that people say to Adam as he goes about the world are things that people have said to me, or to members of my family. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been asked: “Where are you from? No, where are you really from?”

So in one way, I just wanted to write truthfully about my experiences. But I do also believe that fiction can help us understand other people’s experiences. So I hope that if you read Tyger and enter Adam’s point of view, you’ll grasp at once why it’s such a problematic question – because its implication is that you can never, ever belong in the place where you live, and have always lived.

I […] believe that fiction can help us understand other people’s experiences.

RK: It feels like it was born to be a classic. Did you feel while you were working on it that you were creating something important?

SFS: Thank you so much! I was just trying to make Tyger the best book I could make it – which is what I do with all my books. Of course, you hope other people will love your book as much as you do, so it means more than you can imagine to hear that someone else has enjoyed it, and got something out of it.

RK: Who do you have in mind as a reader when you write?

SFS: First of all: me! I write the books that I most want to read myself.

But beyond that: everyone. I believe the books we call “children’s books” are really books written for an audience that includes children, but excludes no-one. They are books for everyone. So I’m always delighted when any reader engages with my books, whatever their age, and whoever they might be.

I believe the books we call “children’s books” are really books written for an audience that includes children, but excludes no-one.

RK: The illustrations are exquisite – did you always know you would be working with an illustrator or was the decision to use one made after you submitted the book to your publisher?

SFS: Thank you, I love the illustrations too! They’re by Dave McKean, who’s illustrated all my books, so it was always the plan for him to illustrate Tyger. We looked at lots of classic children’s book illustration when we were discussing ideas for Tyger. But Dave also brings things to the process from his work in comics and graphic novels, cinema, graphic design and fine art that you’d never normally see in a children’s book. And there are things he does with his art that could never be done with words alone…

SF Said’s Website, Twitter and Instagram

Rachael King

Rachael King is a former literary festival director and a writer for adults and children. She’s the author of two middle grade novels: Red Rocks (2012) and The Grimmelings, which is a finalist in the 2024 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults.